With the rise of e-commerce and more discerning consumers, the recent growth of malls in China risks becoming redundant.

On the third floor of the Huan Long shopping center in Shanghai, all is quiet. The mall, adjacent to one of the city’s major railway stations, has long rows of empty stores, grubby windows covered with fading posters and shop doors chained shut with padlocks. Many areas seem abandoned except for a few lone traders and their children, who sit eating instant noodles, playing card games in dusty corridors and fixated on smartphones with no business to distract them. Even with the draw of the nearby transport links, the mall is inconsistent, grubby and rundown.

“Business has been getting worse year by year,” sighs Chen Weicheng, who has been selling photographic film in his small store for the last 10 years. “Now everyone just buys things online.” But the situation is not straightforward—a cheap glasses market on the third floor attracts some crowds, and the lower floors stock China’s ubiquitous smartphones, cases and covers. Yet the Huan Long center, now over 20 years old, is in no way unique or noteworthy in a city saturated with shopping malls.

An unprecedented amount of retail development and spending has swept into China over the last decade, driven by the country’s rising spending power and a shift to consumerism, and the building frenzy shows little sign of abating—figures from property agency CBRE suggest half of the world’s current retail development is in China. But at the same time, China’s e-commerce market is booming and putting pressure on the need for retail space as a result. Is the country’s retail sector facing massive oversupply?

Shopping Mall Nation

Annual disposable personal income among urban citizens reached RMB 28,844 in China by 2014, up from a figure of just RMB 343 in 1978, government figures show. As people grew richer and spending was encouraged, China’s retail sector was ill equipped to deal with the opportunity. According to the National Retail Federation, while the top 100 retailers had a 57% share of overall retail sales in the US in 2012, in China at the same time the figure was only 9%. Retail was loosely organized and inefficient, and most cities lacked adequate shopping space.

Retailers flooded into the country as demand outstripped supply. Growth in sales was in double digits between 2009 and 2013, while official government figures show retail sales rocketing to RMB 26.24 trillion in 2014.

According to the International Council of Shopping Centers, in 2009 there were 2,293 shopping malls in China. By 2013 this had reached 3,450, and by some estimates there will be almost 5,000 by the end of 2015. This development was encouraged by enthusiastic local government land sales, and these bodies were also keen for the regular tax income and employment opportunities that retail development offers. A newly-urbanized population quickly adopted going shopping as a national hobby.

With few experienced retail developers before the boom, the sector remains extremely diverse. According to figures from property agency Jones Lang LaSalle, only about 15 developers in China have built more than 10 malls, with the majority building only one or two.

And the development drive continues. China is set to become the world’s largest retail market by 2018, according to figures from PwC and the Economist Intelligence Unit. That is being driven by the country’s ever-increasing riches—McKinsey estimates that 75% of the mainland’s residents will be classified as middle class by 2022, compared with just 4% in 2012.

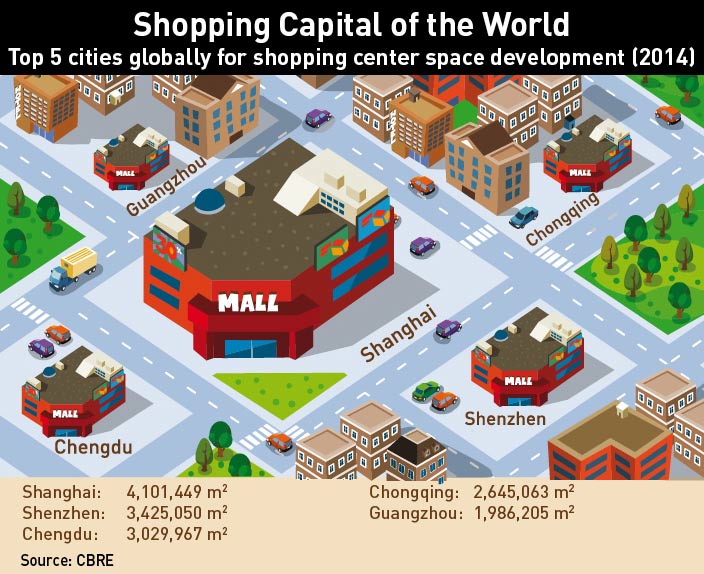

New retail supply in Shanghai and Chengdu to be completed this year and next is expected to reach 3.3 million m2 and 3.2 million m2, respectively, and eight of the 10 most active cities for shopping center construction globally are in China, according to CBRE. According to their research, less than a fifth is being built in prime retail areas by experienced mall developers.

New retail supply in Shanghai and Chengdu to be completed this year and next is expected to reach 3.3 million m2 and 3.2 million m2, respectively, and eight of the 10 most active cities for shopping center construction globally are in China, according to CBRE. According to their research, less than a fifth is being built in prime retail areas by experienced mall developers.

“Most of the real estate developers have looked at the mall as something to be sold,” says Melanie Alshab, Managing Director of Kensington Asset Management. “When you build something to sell it, you’re not interested in making an investment to reduce your operating costs, you just want to see it finished and get a return… nobody stopped to look at the fundamentals of retailer demand or shopper demand.”

Cyber-Spaces & Other Places

While shopping malls grew in record numbers, China has also been setting records as the world’s largest online market, surpassing the US in 2013. Chinese shoppers spent $440 billion online in 2014, according to research group Forrester. This figure is forecast to rise to $1 trillion by 2019. Online retailers have found a market ripe for innovation, particularly in lower-tier cities with few retail options.

According to research from Bain & Company, online retail in China will grow three times faster than overall retail, with half of total online sales coming from third-tier cities and below by 2018.

Inevitably, this is being felt in physical retail. Some retailers, such as British fashion brand Topshop, have chosen to make their China debut via an online platform; others are reducing their store portfolios in the country. In March, Marks & Spencer announced it was closing five stores in and around Shanghai, instead serving these secondary cities through its partnership with Alibaba site Tmall.

Stores are also facing challenges around ‘showrooming’, where consumers look at products in-store and then buy online. In shopping malls where many rental agreements were based on a percentage of sales, falling in-store purchases can have serious knock-on effects for landlords reliant on turnover.

Shoppers also don’t distinguish between online and offline shopping. As Bain puts it: “Increasingly, the transactions themselves are becoming just a single step in an online consumer journey enabled by digital capabilities. That journey begins when a customer goes online to discover and research products. It continues when the customer decides to purchase and makes the transaction. Then, in surprisingly large numbers, China’s shoppers go back online after a purchase to share their experiences.”

Developers around the world have to adapt to the new pressures in retail. Challenges of online commerce are by no means China-only phenomena, but in China the risks are exaggerated because it coincides with a huge amount of space coming to market.

Wanting More

It’s not just e-commerce that is changing expectations among China’s consumers. Shoppers in China are increasingly global, and consequently expectations at home are changing. This is not just on price, but also around service. One luxury outlet mall in Shanghai, the Florentia Village in Pudong, offers free training for tenants’ staff to bring service up to European expectations.

Moreover, consumers are increasingly attracted not just by retail, but by the overall experience. The K11 ‘art malls’ are a key example of this, hosting a Monet exhibition in its shopping mall in Shanghai in 2014, pumping out a distinct scent so the mall always smells fresh, along with setting up a dedicated team to manage the K11 art shows.

Increasingly, malls are home to cinemas, ice-skating rinks, bowling alleys, medical services and language schools. Haichang Holdings, a China-based theme park developer, has ambitions of creating small marine parks in retail centers. The IFC Mall in Shanghai hosted a year-long exhibition of miniature collections, which it says generated a 13% increase in traffic and achieved $4.5 million in revenue during the campaign’s run. Chengdu IFS turned historic relics discovered during construction into an “antiquity plaza”.

“Retail malls have had to evolve to adapt to the changing marketplace,” says Trevor Vivian, director at architectural firm Benoy. “In China, there is a real demand to create a destination away from home, a place where you can relax, explore, be inspired, dine, socialize, be entertained, and of course still shop. It is now the diversity and mix of uses that is appealing to the public… the market is becoming more aware of designing for a location and not duplicating models city to city.”

Adapt or Die

As malls allocate more space to non-retail uses such as cinemas, the overall size needs to increase to make sure the landlord’s turnover is not damaged. Consequently, China is home to swathes of ‘mega-malls’.

The average new mall in China from 2005 and 2014 was 86,000 square meters in gross floor area—although most modern malls are between 100,000 square meters and 200,000 square meters—and a study from financial services group BNP Paribas found that developers such as Dalian Wanda allocate as much as 50% to leisure.

These larger malls require more tenants, and are more vulnerable as the landlord has to allocate consistently high levels of management across all floors and areas. The New South China Mall in Guangdong, more than twice the size of the biggest mall in the US, was classified a “dead mall” by one study in 2013; eight years after opening only a smattering of the 2,350 stores are occupied; largely due to a misunderstanding that few residents in the industrial region have spare money for the type of attractions the mall offers.

But landlords are gradually developing these previously neglected skills of mall management as developers tend towards building a center not to sell, but to run as a business.

For a long time, tenant mix has been led by the tenants themselves (for instance by going bust, or by rearranging their portfolios), but now resourceful and proactive landlords are experimenting with the placement of tenants, including pop-up stores, markets and flexible retail space, to keep the retail environment varied and engaging. And the concept of attracting a mall anchor, typically a department store given their size, is now focused on securing brands like Apple or iMAX, which landlords know will draw crowds.

“The ability for developers to create unique differences between malls to some extent depends on how smart the landlord is, and how smart the asset manager is in terms of thinking outside the box,” says James MacDonald from property consultancy Savills.

Retail developers are also testing driving sales from online-to-offline (O2O), such as ‘click and collect’ services where shoppers buy online and collect in-store. Other examples of O2O include augmented reality supermarkets in malls, already experimented with in China, where shoppers can position themselves in a specific location and digitally purchase an item seen on their smartphone screen. Other concepts involve a customer making a purchase in-store where the item goes back on the shelf after payment and the product is delivered to the consumer’s home.

This also plays into the trend of ‘reverse showrooming’, where customers go online to research products but head to a physical store to complete the purchase. Burberry is seen as one of the market leaders in the area of “bringing online in-store” by transforming the in-store experience with a live connection to the brand’s website, digital mirrors and touch points that can be shared through social media.

O2O retail in China has taken hold more easily because it lacks established consumption patterns and loyalties, plus consumers have easily and rapidly adopted mobile e-commerce. Mobile payments in China have seen massive growth, reaching $965.1 billion in 2014, according to consultancy iResearch; 391% growth on 2013.

“It’s not just what technology we have at the moment, but also making sure your mall is flexible enough with the IT infrastructure in place to adopt new technologies which haven’t even been created yet,” says MacDonald.

Developers are also increasingly aware of which brands are most vulnerable to forces of e-commerce. Bain research suggests consumer electronics registered a 20% online retail penetration rate, and the penetration rate for apparel rose to 18% in 2014.

“As this phase of experimentation produces winners and losers, the onus will be on mall owners in China to pick brands for their malls that are managing the transition to multichannel strategies successfully,” explains Steven McCord, lead China retail analyst at property consultants Jones Lang LaSalle.

Landlords are largely being led by both shoppers and retailers in the area of O2O retail. One of China’s biggest store chains Suning is an example of a Chinese brand repositioning itself as a multichannel retailer. The chain had more than 1,500 stores and a solid reputation for home appliances through big-box retail outlets before it started to be impacted by e-commerce. In 2013, it rebranded itself as an online to offline retailer—store and online payments, supplies, inventory and deliveries were integrated, free Wi-Fi was introduced and staff were given targets to sign customers up to social networks and register online.

Leading retailers already understand the balance between offline and online, multi-channel retailing and how consumers often come to inspect products in-store, says Trevor Vivian. “It’s this balance that mall operators need to embrace; with the introduction of entertainment, leisure, education and events to drive traffic to these developments, how can consumers interact both online and offline?”

Where retail innovation in other markets has been largely powered by retailers and developers, in China much of the innovation is driven by the country’s e-commerce giants. A tie-up in August 2014 between Dalian Wanda, search engine Baidu and social media giant Tencent agreed to build a massive e-commerce platform specifically focused on how to “integrate offline with online”, melding Baidu’s search capabilities, Tencent’s popular WeChat messaging network and Wanda’s bricks-and-mortar infrastructure.

“Mall design will have to evolve in China as landlords realize they have to be more flexible in terms of retail layout,” says Alshab. “Good mall developers have always done this, but now they really have to be flexible in terms of the way stores are laid out. It might be that one brand wants multi-storey stores in the future, or wider stores in the future, or to use flexible space outside its shop—all kinds of things that the landlord needs to adapt to.”

Matthew Smith, Global Head of Market Development for the Internet of Things at Cisco, also points out that there can be efficiencies for mall landlords who start to “think hi-tech”. “Currently, operators in most large malls do not have direct relationships with customers—the growing use of apps and wireless connectivity will allow this to change,” he says. Operators will be able to provide data on footfalls and the flow of people, and promotions can be sent to handheld devices at the right time.

Closing Time

Many of these concepts are still at a very early stage in China, and there will still be malls that fail to adapt, especially in lower-tier cities.

The PwC/Urban Land Institute report Emerging Trends in Real Estate Asia Pacific makes a particularly downbeat assessment, warning “although second- and third-tier cities have successfully built up their local economies, real estate prospects have deteriorated rapidly after local governments sold too much land too quickly, resulting in oversupply in almost all sectors.” China’s second-tier cities have now fallen to 22nd in the report’s attractiveness rating.

“The way I see it is that downtown areas in every city can probably support a few innovative ‘cool’ malls, which makes sense because going to the city should be about seeing something special,” concludes McCord. “The difficult question is what to do about the classic suburban mega mall, which is big, certainly not tourist-oriented, and needs to fulfill people’s more regular needs and frequent trips.”

There are few alternative uses for shopping malls—some can be converted into other uses such as arenas, but their size, bulk and lack of windows often makes repositioning difficult. Property experts expect to see a significant number of malls come to market in the near future, with opportunity for consolidation, repurposing or redevelopment for the more able developers.

The retail market is settling after a mad rush from consumers and inexperienced developers over the last decade, while being buffeted by the new forces of digital retail. But what the next few years promise is an increasingly wide gap between successful malls and failing ones.

“To be successful in the future, retail will become one part of an overall experience within a destination,” concludes Benoy’s Vivian.

There’s no doubt that the concept of syncing offline shops and online activity will dominate retail innovation this decade, with China’s digital giants positioned to lead the way. Malls in strong locations that offer strong combination of shops, a good environment, a good retail experience and a strong location can prosper. Those who fail to keep up are likely to be left behind.