How will the growing strength of domestic venture capitalists impact the development of China’s tech system? Domestic venture capital is muscling out international VC funding in the China market. What does this mean for startups?

A decade ago, most venture capital (VC) investments in China were led by foreign funds. Today, the vast majority are led by Chinese VC funds and foreign capital is hardly seen. It’s a turn-around that has big implications for China’s growing tech sector and for its integration with the rest of the world.

On Forbes’ most recent list of top 100 venture capitalists globally, Chinese investors snagged 21 of the places, up from 17 last year. Importantly those VC funds and their activities were not focused on Silicon Valley but on ventures in China.

Decades of economic reforms in China have given high-quality startups the opportunity to thrive, and also provided rich prospects for investors. A yearslong swell of venture capital activity in the country has created a number of so-called “unicorns”—privately-held startups valued at more than $1 billion. Until a few years ago, most of them would have been looking for foreign VC support as a prelude to a listing on NASDAQ, or another foreign stock exchange. No longer.

While foreign heavyweight US champions, such as Sequoia and Matrix, have been the main players in the field in the past, domestic Chinese VC funds such as Qiming as well as VC offshoots of China’s tech titans led by Alibaba and Tencent, have become far and away the biggest investors in Chinese startups.

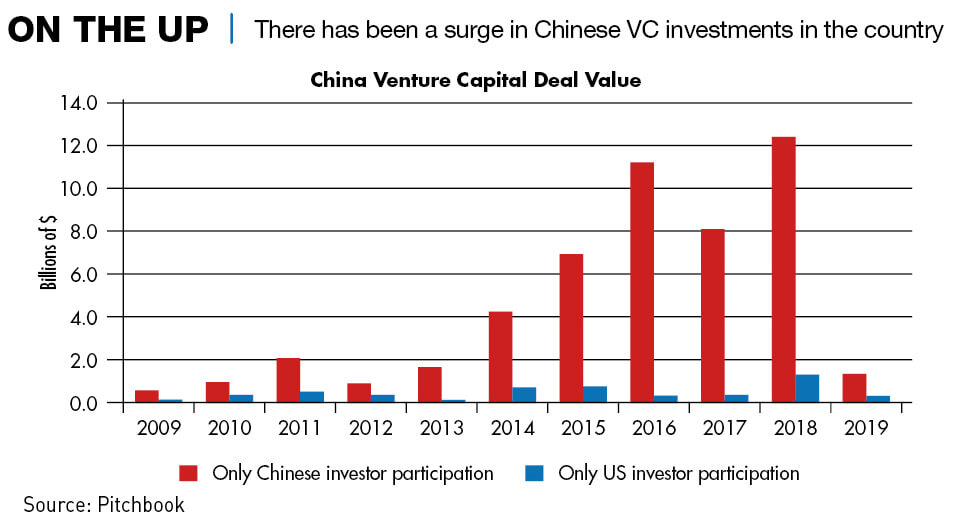

The total value of completed VC deals in China that only involved domestic funds reached a record $12.5 billion in 2018, according to data compiled for CKGSB Knowledge by Pitchbook. Meanwhile, the value of US investor-only VC deals done in China was roughly just one-tenth of the size, at $1.27 billion. Some 463 VC deals were completed last year with only Chinese funds participating, while just 47 deals were done with only US investors onboard.

The rise of domestic VC in China and its recent overshadowing of foreign VC has “been driven by the fact that a lot of the foreign firms—Kleiner Perkins being an example—started a branch in China, but it was a train wreck,” says Gary Rieschel, managing partner of leading China VC firm Qiming.

“They just never got off the ground. New Enterprise Associates started a branch, pulled it, started it again. Greylock Partners got rid of people. Because it was really hard to establish trust with the people in China back in the fund headquarters when they were making investment decisions. The funds that were able to actually establish local subsidiaries and raise capital specifically for China have just grown dramatically.”

Investors’ paradise

Chinese startups raised more cash than their peers in the US for the first time ever in the first half of 2018—$56 billion versus $42 billion—according to a study conducted in November by data provider Preqin and French business school INSEAD.

That was largely thanks to a huge $14 billion funding round in June 2018 for Ant Financial Services that gave Alibaba’s financial affiliate a post-fundraising valuation of $150 billion. Other multibillion-dollar investment rounds that closed in China last year included: Didi Chuxing’s late-stage financing for $4.6 billion in February; $4.0 billion for Meituan-Dianping in April ahead of its Hong Kong listing in September; and the $3.0 billion for ByteDance in October, the startup that created the popular video app TikTok.

In recent years, VC activity in China has been concentrated in tech and other emerging industries, such as artificial intelligence, new energy vehicles, new materials and robotics, says Wang Dan, an analyst with the Economist Intelligence Unit. The Chinese government has also been very supportive of the trend.

“Some government reforms stressing the use of digital transformation have also attracted VC into traditionally non-digital fields such as health care and education,” says Wang.

“AI is extremely hot because everyone thinks it is going to completely disrupt the way things are done,” says Joe Chang, a Shanghai-based partner at Eight Roads, the proprietary VC arm of Fidelity International. “That’s key for a country like China, to be able to leapfrog the US. There’s going to be a lot of value creation, and value destruction.”

Domestic VC in the spotlight

China’s central government has driven mass entrepreneurship by boosting support to startups and small-business owners with generous financial incentives in the hope of accelerating growth and generating jobs. Beijing also stepped up policy support, not just through subsidies but also by simplifying the registration process for startups—entrepreneurs can set up small businesses in less than a week with only a few thousand RMB, without needing an office or registered capital.

State-backed funds have become some of the biggest players in the VC industry. One local government-backed VC firm, Shanghai Information Investment, was founded in 1997 with the mission to fund companies developing Shanghai’s IT infrastructure. In 2007, the Ministry of Science and Technology launched the first of many state-owned “guidance funds” to encourage more investment in tech startups. There were at least 2,041 guidance funds in operation last year, with total funding reaching RMB 5.3 trillion ($742 billion), according to Pitchbook. More recently, in 2017, China’s central government launched the RMB 100 billion ($14 billion) China Internet Investment Fund to finance and support domestic internet companies.

“The state-funded money going into the venture market has been extraordinary in the last few years,” says Rieschel. “The government has all sorts of local venture fund deals at city level, county level and provincial level, so it’s a huge player in terms of the amount of capital deployed.”

One story that illustrates the current VC environment is the example of Reap. In mid-2018, Daren Guo and Kevin Kang started approaching VC firms in China and overseas for seed capital to fund Reap, their Hong Kong-based startup that enables SMEs to pay for business expenses using credit cards. The numerous successful Chinese companies that have gone from zero to blockbuster flotations in a short space of time have spoiled local investors to some extent, raising the bar for domestic startups and inflating expectations about what they can achieve.

“China is a market where if you’re able to hit the problem and get distribution at scale very quickly, the network effect allows you to scale incredibly quickly because of how large and interconnected the country is,” says Guo. “There were a few investors that we talked to in China that have these expectations for startups and companies that do not share some of China’s unique market dynamics.”

“You think about a lot of the success stories in China that have accelerated to massive scale in a very, very short amount of time. It has to do with the network effect. You really have to keep investor expectations of that in check, if your business is not fully immersed in China,” says Kang.

The huge levels of liquidity and the plethora of startups seeking cash means domestic VC players do not necessarily need to be picky when it comes to backing new businesses.

“Some of the ones we talked to were just very almost just like capital machines,” says Kang. They’re dispensing money because they have so many opportunities to look at. Especially in China, there are so many seed-stage companies out there, it makes more sense to just spread your money around and see what works out.”

The scattergun approach of some Chinese VC firms ties into a shorter-term mentality compared with their international peers, says Jiang Xiaodong, managing director of Shanghai-based Long Hill Capital.

“Global funds seem to be more long term-oriented, simply because in many cases, global partners have been doing this longer,” says Jiang. “They are more mature, and they know the nature of cycles, so they’re not necessarily after quick riches because they know that it’s not possible in most cases.”

Chinese VC firms are arguably less efficient than international funds because of their lack of diversification in investment, says Wang from the EIU. “Too much capital is always chasing too few companies, and usually ends up in a narrow range of technology and consumer sectors. Their decisions are often driven by government policies and market sentiment. Their exit strategy is limited too, given that IPOs in mainland China are cumbersome. Yet the Shanghai Tech Board may provide a way to cash out for some VCs.”

BAT comes out swinging

The most active VC firms in China were once VC-funded startups themselves. Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent Holdings, known as BAT—China’s first generation of super-unicorns—command significant sway in the economy and have become formidable investors in startups.

The BAT companies started with a singular business objective—Baidu in online search, Alibaba in e-commerce, and Tencent in social networking services—but they have now built sprawling digital empires that challenge, at least in the China context, the likes of Google, Amazon and Facebook. They have pervasive platform strategies that successfully extend into nearly all sectors of the Chinese internet, and by dominating Chinese screen time and e-commerce spending; the BAT trio have made nearly a thousand VC investments through a variety of vehicles and subsidiary companies.

“These guys can be kingmakers, particularly in the consumer sector,” says Chang. “They’re important players. They’ve created even more massive platforms than United States players, from which to service customers—and consumers in particular.”

Tencent and Alibaba have become especially adept at picking promising young Chinese companies that are generating enormous wealth early in their development. Tencent invested in 31 out of China’s 202 unicorns by the end of March, while Alibaba had funded 21, according to the Shanghai-based Hurun Report’s latest Greater China Unicorns Index. This ranked the two companies ahead of well-known VC names, including GGV Capital, Matrix and Qiming.

“They have been far more aggressive than their US counterparts in pursuing investments in the unicorn space,” says Rieschel.

As Chinese consumers rapidly adopted internet and mobile technology, the BAT firms expanded into new business models to address consumer needs—in the process, becoming reliable sources of capital for startups. Ever fewer promising young Chinese companies seem able to escape the reach of their insatiable investment teams—by the time early-stage companies in China hit a $5 billion valuation, 80% of them have accepted funding from one of the tech triumvirate.

The BAT trio not only invests in early-stage companies, but also provides an attractive exit channel by acquiring many of the companies in the long run. Significant investments in unicorns as well as smaller tech startups are part of the platform-based strategies that BAT have adopted to expand horizontally and to embed themselves in the daily lives of Chinese users.

Continued investment in Chinese startups also allows the BAT firms to increase the stickiness of their platforms and to act as a one-stop shop for all entertainment, shopping, finance, and other needs. They have strong alliances with Chinese local governments, which provides strong tailwind for growth.

Challenges

Foreign VC firms were originally very attractive for Chinese startups because they provided a route for listings in the US markets, but those markets have become less attractive too Chinese entrepreneurs in recent years for several reasons, most importantly increased oversight of the companies by the US regulators combined with more relaxed conditions for listing on the China stock markets.

Domestic funds based in RMB are able to invest in a much wider range of sectors, and companies are not restricted from listing on domestic exchanges. Foreign VC funds, in contrast, face significant hurdles in exiting on Chinese exchanges. The Chinese equity markets also typically provide much higher valuations for Chinese startups, and ever-stricter controls on the cross-border movement of funds also makes Chinese entrepreneurs much less interested in raising US dollars, and much more interested in raising RMB funds domestically.

Foreign VC funds also face policy risks. Some fund managers are conscious of the fact that opposition exists from within the central government over concerns that foreign VC funding could undermine its close-knit system.

Looking to the future

Nonetheless, as the world’s largest single market, China still boasts vast potential in the consumer sector and services, and foreign VC investors have certainly not abandoned it.

China is now itself originating more and more technological and scientific advances, particularly with government support, and foreign VCs often want in.

“In the past what you had was that most of the real invention that we celebrate today occurred in the US, and then was brought over to China,” says Rieschel. “You had localization and innovation on that, but the real core invention was overseas. I think you’re going to see the Chinese become more inventive. You’re going to wind up having fundamental breakthrough technologies start to hit the market from China.”

While Chinese VC firms have to a large extent taken the spotlight for now, fund managers don’t expect international outfits, and the need for them, to disappear any time soon.

“The international limited partners are still more mature in terms of the way they approach investing,” says Long Hills’ Jiang Xiaodong. “Going into the future, the best general partners will want the best limited partners, not just someone who’ll write a check, but someone who really understands the private equity and venture capital business. Right now, they’re still mainly overseas.”