China’s massive outward direct investment spending spree has stalled after a series of policy shifts and strong capital controls. What happens next?

China’s outbound investment has fallen dramatically off its highs, with the days of massive growth in Chinese investments around the world clearly over, at least for now.

The sudden pullback in China’s non-financial outward direct investment (ODI) in the past couple of years follows a series of policy shifts and further strengthening of controls on the movement of capital abroad.

After reaching its peak in 2016, China’s ODI took a 30% nosedive in 2017—its biggest drop since 2003. That was followed by meager growth of 0.3% in 2018 for a total of $129.8 billion and then another drop of 1.1% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2019.

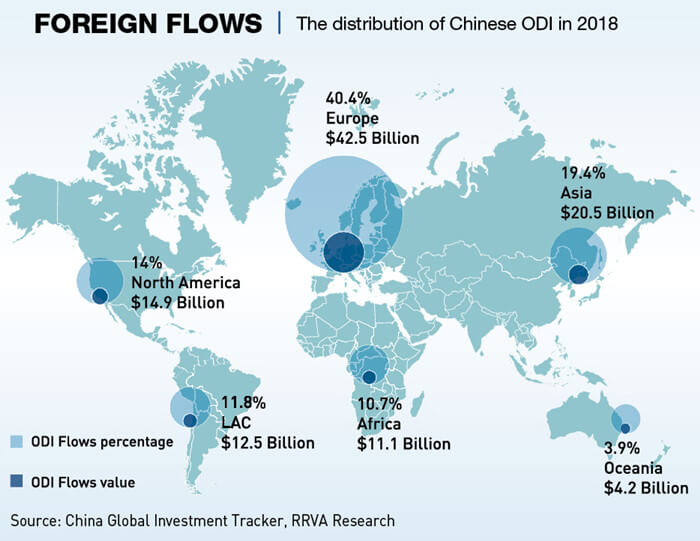

From a regional perspective, the changes are even more dramatic. In 2018, Chinese ODI into North America and Europe fell by a combined 73%, with total ODI into the two continents amounting to only $30 billion compared to $111 billion the previous year. This was only slightly cushioned by increases in ODI into countries with Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, which increased by 8.9%.

Years of red-hot growth

China’s foreign spending spree took off after its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, an event that hugely accelerated the country’s economic growth and the amount of money it had available for further investment. In what constitutes one of the most astonishing shifts in the history of economics, China went from being ranked 23rd globally for ODI in 1999, with $27 billion, to becoming the world’s second-largest ODI source after Japan in 2016, with $196.2 billion.

Between 2000 and 2016, the state relaxed regulations on investing abroad and streamlined the registration and approval of ODI projects to support foreign mergers and acquisitions (M&A), particularly those that gave Chinese investors access to raw materials and the technology needed to upgrade the country’s manufacturing sector.

“When I started working on M&As after the turn of the millennium, it was mostly about foreign companies entering the Chinese consumer market or setting up export-oriented production in China,” says Sun Yi, a Chinese management consultant and partner at Ernst & Young. “But since 2010, I mostly deal with Chinese ODI, which reflects a shift in the overall trend.”

Chinese investors’ initial focus in Germany, Sun says, was on the automotive, machinery and pharmaceutical sectors so that they could access technology. Motivations have since diversified, such as how Chinese corporations and private equities are now also considering their reputations by buying European fashion brands.

An example of this is how China’s investment fund Fosun International in 2018 became the majority shareholder of both Austrian lingerie maker Wolford and French fashion house Lanvin, luxury brands which have long been running at a loss.

The big 2017 dive

The sharp decline in ODI recorded in 2017 has been generally attributed to the stiff capital controls and the slowdown in China’s economic growth. The government has been anxious to tame “irrational” capital outflows, effectively curtailing the ODI binge, especially into the real estate, sports and entertainment sectors.

In a measure to slow the flow of private wealth out of China, since early—2018 individuals are only permitted to remit a sum of RMB 100,000 ($14,500) abroad per year, regardless of how many separate bank accounts or ATM cards they have.

As a second layer of control, the state has implemented measures to manage outbound payments. Before each cross-border payment for an outbound investment of a Chinese enterprise, the investor needs to obtain approval from multiple Chinese government departments to remit money across the border to pay for the deal.

This includes potential investors being required to submit an audit report of the foreign company to be purchased if the target company exceeds the investing company’s size by more than 50%, which, according to Sun, “no target company is happy about during late-stage negotiation.”

Banks are under strict obligations to ensure that money only leaves the country in compliance with the relevant requirements.

“Authenticity checks have become stricter since 2016, adding considerable uncertainty to any M&A negotiations, as it is often not clear until the very last minute that all paperwork is on the table,” says Jakob Riemenschneider, partner at law firm Taylor Wessing in Hong Kong.

“There has also been direct government interference. Prominent companies, such as the real estate developer Dalian Wanda Group, the airline operator HNA, the insurer Anbang Group, or Fosun have had to dispose of overseas investments after the government branded these investments as ‘irrational’,” he adds.

Riemenschneider went on to explain that the main challenge for Chinese companies’ existing ODI investment portfolios, is that business leaders may be concerned about which of their investments will come under scrutiny next.

“And on the project implementation level, many foreign business partners of Chinese companies consider the multiple approval and filing procedures for outbound investments as an unpredictable factor that may slow down a transaction,” he says.

The new normal

Several developed countries have started to perceive China’s M&A purchases of valuable companies in their high-tech sectors as a potential threat to their leading positions.

A number of EU member states have begun upgrading investment screening systems, which has raised the bar for Chinese takeovers. A new EU investment screening framework encourages member states to specifically review state-supported investments in sensitive technologies and critical infrastructure. According to a report published by Rhodium Group and the Mercator Institute for China Studies in March, an estimated 82% of Chinese M&A transactions in Europe in 2018 would have fallen under at least one of those criteria.

The strengthening of review mechanisms has already impacted Chinese investment patterns. Germany blocked Chinese company Yantai Taihai’s bid to purchase toolmaker Leifeld, citing security concerns. This followed the German government indirectly thwarting China’s state-owned State Grid Corporation of China from acquiring a share in power distributing company 50Hertz. Rather than vetoing the deal, Berlin instructed the government-owned KfW bank to buy the shares on offer.

Meanwhile, in the United States, inbound ODI from China is being screened with renewed gusto for national security risks by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS).

According to data compiled by the Pillsbury law firm, CFIUS’s clearance rate of US-China deals has fallen to under 60% under US President Donald Trump’s administration, compared to more than 90% under the Obama administration.

On the China side, while ODI has been slowed by Chinese regulators concerned by money leakage, the approval process for “rational” ODI has become more efficient, with the amount of paperwork needed to be filed in an ODI application being reduced.

According to data provided by Taylor Wessing Hong Kong, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the General Office of State Council in May 2018 promulgated a “Guiding Opinion on the Further Promotion of Making Examination and Approval Services More Convenient for the Public” to serve as the latest policy basis of the so called “one-stop services” for ODI applicants.

“Now people know where to apply, how long it takes, and how to deal with the banks and foreign exchange controls in the ODI process,” says Wang Jiawei. A Chinese lawyer, he specializes in advising Chinese companies looking to invest in Europe in his position as the head of the China Desk of Rödl & Partner law firm.

“The number of unregulated areas is steadily decreasing, as China’s governmental authority has been standardizing the procedures and we are also witnessing that China’s judiciary system is making huge progress especially in terms of dealing with IP protection, cross-border dispute settlement and so on, which provides a strong basis for various Chinese ODI projects,” he adds.

Wang explains that Chinese buyers have learned lessons from the past and are nowadays much better prepared in overseas M&A projects than they were at the beginning of China’s ODI trend.

Meanwhile, BRI also helps

Chinese ODI into developing countries on the back of BRI infrastructure projects, is on the rise, although marginally, and there is a growing sense of concern amongst Chinese officials about the return on investment for such projects in countries such as Pakistan and Venezuela.

“The economic reality is that Chinese investors prefer developed markets, rather than chasing potential opportunities in BRI countries,” says Nick Marro, a China analyst with the Economist Intelligence Unit.

In 2018, BRI spending amounted to over $15 billion, or 13% of China’s total ODI, according to the Ministry of Commerce. In the first two months of 2019, such investments rose to make up 14.6% of China’s total ODI.

China’s Global Times reported in April that its surveys indicate that many Chinese companies and top industrial leaders have shown enthusiasm to ride on the momentum started by the BRI.

“Over the past five years, we have achieved significant results, all participants have seen tangible benefits and recognition, and participation in the BRI has continued to improve,” said Xiao Weiming, director general of the Department of General Affairs of the Office of the Leading Group for Promoting the Belt and Road Initiative.

Reading the tea leaves

According to Loletta Chow, Global Leader of China Overseas Investment Network at EY, China’s overseas M&A activity declined significantly in the first quarter of 2019 because Chinese enterprises generally are taking a more prudent approach to avoid risks amid intense global trade friction, increasingly complicated geopolitics and the slowdown in many major economies.

“With slipping investment confidence in Europe and North America where foreign investment policies were tightened and uncertainty increased, many Chinese enterprises turned to Asia,” Chow said in a May 2019 report.

“Meanwhile, with economic transformation and upgrade, sectors such as TMT [technology, media and telecommunications], life sciences and consumer products were expected to attract more capital,” she added.

In a November 2018 report, Chow had noted that in terms of sector, energy infrastructure has become the key target for Chinese enterprises to invest overseas.

From January to September 2018, the deal value of overseas M&As in the power and utilities sector increased four times year-on-year to $31.3 billion, representing nearly 30% of the total value of China overseas M&As and became the most attractive sector among Chinese investors.

From what Rödl & Partner’s Wang sees on his desk on a daily basis, there is a tendency toward diversification in Chinese ODI projects, with the focus shifting from the Business-to-Business (B2B) area over to Business-to-Consumer (B2C) projects.

“It’s normal that major economies are continually strengthening their mutual economic ties, and the more these two economies get familiar with each other, the more new investment fields will be generated,” says Wang. “Nevertheless, Chinese investors’ interest in automotive, medical and modern equipment has remained strong, which is also in line with China’s plan to upgrade its industries.”

Alibaba, China’s top cross-border e-commerce platform, for example, is leaping ahead of its Chinese competitors such as JD.com and NetEase’s Kaola—by selecting Southeast Asia and Europe as a focus for expansion and increases in ODI.

Alibaba’s logistics arm Cainiao is setting up a 220,000m² logistics infrastructure hub at Belgium Liege Airport, with an initial investment of €75 million ($85 million). This follows the establishment of similar hubs in Dubai, Kuala Lumpur and Moscow.

“Cross-border sales represent the fastest growing segment in China’s e-commerce market, and the firmer Alibaba gets its boots on the ground overseas, the greater its edge it has over its rivals,” says Olaf Rotax. He is managing director of dgroup, a consultancy for digital transformation belonging to multinational professional services company Accenture.

Whither ODI

As for the future trajectory of Chinese ODI, it is important to keep in mind that China is now the second biggest economy in the world, and it is not going to relinquish that position or the global financial clout that it represents.

“There are no indications that Chinese ODI will lose its significance,” says Rotax. “But there are indications that money is not being spent as generously and that Chinese investors are expecting higher returns on their ODI, making them choose their targets much more carefully than they did in the past.”

Some analysts have been speculating as to whether this marks an end to China’s soaring ODI, but a conclusion that the Chinese ODI era is over is premature. Amongst other factors, the trend of the past few years mirrors activity elsewhere—overall global cross-border investment flows dropped by double-digit rates since 2017. The bottom line is that Chinese ODI is going to be an important and permanent factor on the world stage from now on, even though the goals and targets will change.