The scale of the challenge created by China’s rapidly aging population and falling birth rate is only now becoming clear. Will China fall off a demographic cliff?

The scale of the challenge created by China’s rapidly aging population and falling birth rate is only now becoming clear. Will China fall off a demographic cliff?

The scenario sounds almost dystopian. The business of old people’s homes is booming, schools in many parts of the country are closing because there are not enough children to fill them and factories are struggling to find workers.

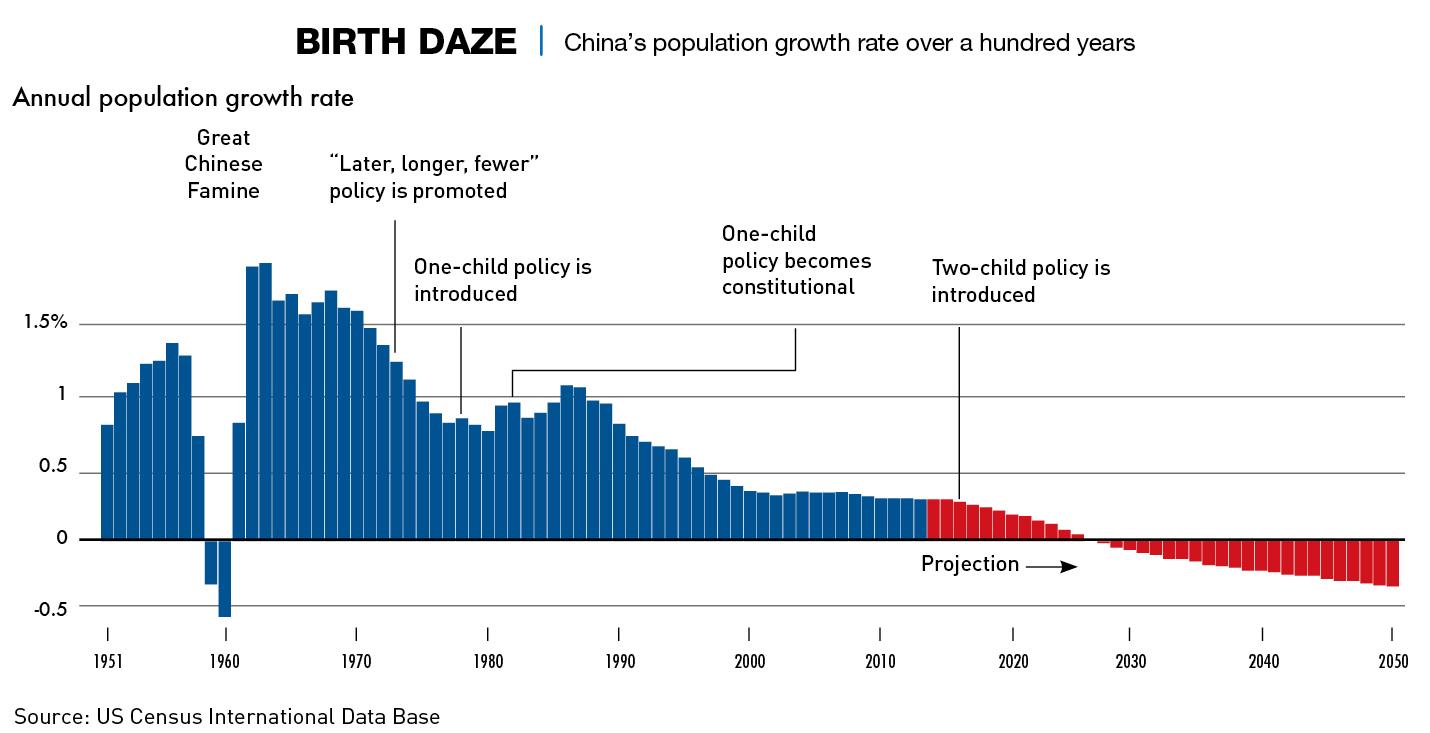

The government’s decision in 1978 to force couples to have no more than one child was meant to reduce pressure on the economy in ensuing decades. While the policy was relaxed in 2015 to help reverse population decline, birth rates are still falling, exacerbated by the fact that many young people now seem uninterested in having more children. Others have no interest in getting married or having children at all.

The population, currently 1.4 billion, is forecast to peak during this decade before moving into a period of “unstoppable” decline, according to a government report released by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

This comes at a time when many other parts of the world, including India, the Middle East, Africa and South America, are experiencing continuing population growth. This stokes their economic growth through the ready availability of labor and consumers. There are deep economic implications to China’s demographic turnaround and no easy solution is at hand.

“On a scale of one to 10, I would say China’s demographic problem is sitting at an 11,” says Francis Bassolino, managing partner of investment advisory firm Alaris in Shanghai. “Demographics is basically economics, it’s the fundamental driver. And they’re going to fall off a demographic cliff.”

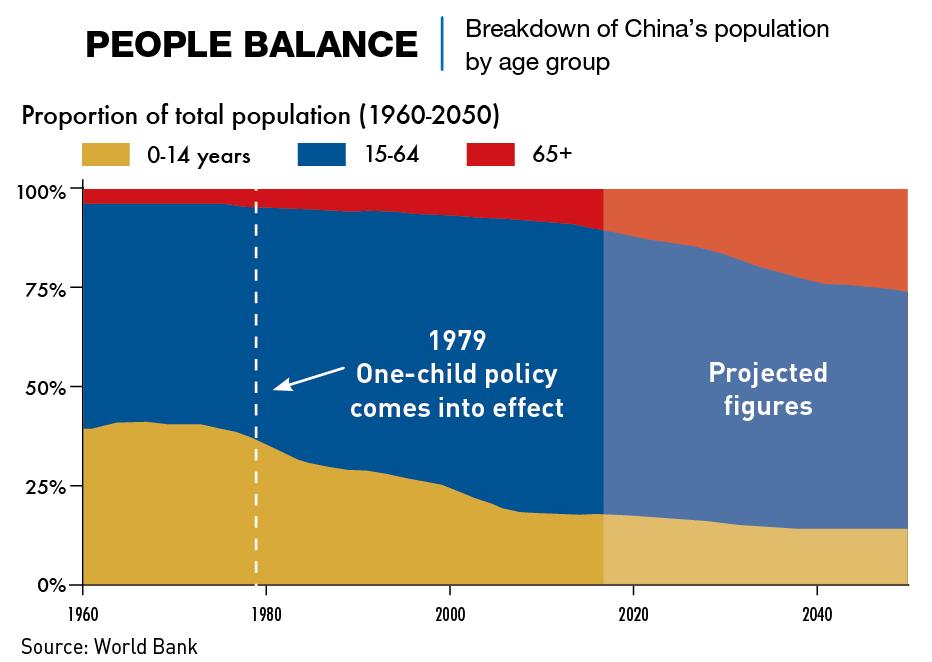

By 2019, 254 million people were aged 60-64. Another 176 million were aged 65 plus. By 2040, an estimated 402 million people (28% of the total population) will be over the age of 60, according to the World Health Organization.

“The numbers really tell the story,” adds Sacha Cody, a business consultant and anthropologist.

“There’s a massive trend toward a population that’s over 65 years old. You’ve got less children and a huge challenge for the social security net. It’s a big challenge for the country.”

One or none

Economic problems are not just the consequence of the demographic dilemma, they were also the cause of the dramatic policy shift in the first place. In the late 1970s, China was desperately poor and cut off from the world. The Beijing leadership had serious doubts about whether the economy could sustain another generation of the traditionally large families that people loved.

From the late 1970s through to the early 2010s, each family, with few exceptions, was allowed only one child. In some places, there were forced sterilizations and abortions, and those who dared to have more than one baby faced prohibitive fines. If anyone associated with the government dared to break the one-child rule, their career prospects would sink. Most famously, in 2013 one of China’s best-known film directors Zhang Yimou was fined RMB 7.5 million ($1.2 million) after admitting to breaching the policy and having several children.

But the one-child policy, coupled with market reforms launched around the same time, helped catalyze China’s modern transformation. Partly due to having fewer bellies to fill, the government turned a hand-to-mouth society into the world’s second-largest economy. Fast forward four decades, however, and the negative impact of the policy is becoming apparent: the number of old people is ballooning and there are insufficient young people to support them.

“At the time, the one-child policy created a demographic dividend,” says Ashok Sethi, author of Chinese Consumers: Exploring the World’s Largest Demographic. “The switch from everyone having many children to having only one child helped the economy significantly, as the labor force was big, while the dependent younger demographic was small.”

“With the one-child policy, the focus was on the immediate need to curb population growth in fear of a Malthusian trap,” says Francesca Hansstein, marketing lecturer at Xi’an Jiaotong Liverpool University, referring to the theory that population growth inevitably leads to a shortage of resources and eventually mass deaths. “Rapid economic development has undoubtedly played an essential role in raising life expectancy, which was 59 in 1970 and went up to 76 in 2018. But there is now a need to work on the solutions to the problem and use some creativity. The fertility rate decline is the main issue to tackle.”

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the one-child policy meant that the government’s investment in education and society was dramatically reduced. But the longer-term consequences are fewer people in the workforce and in the consumer economy and fewer people contributing to pension schemes.

While the population mix was shifting from the late 1970s onwards, the economy was growing rapidly. The gross domestic product (GDP) per capita soared to $866.94 in 2015, from a tiny base of $183.98 in 1979, and in the process a massive middle class was created. In 2020, China declared poverty eradicated.

“People’s lifestyles have changed rapidly in a single generation and now everybody has a sense of ambition,” says Sethi. “They are not content with just meeting basic needs anymore. The kind of competitiveness that exists today, particularly in children’s education and the job market, as well as the huge financial burden that comes with having children, is turning people away from the idea of having more children.”

The relaxation of the one-child policy in 2015 created expectations of a boom in second children, and indeed there was a baby bump in 2016—births that year rose 7.9% to 17.86 million. But every year since, the number of births has declined, to only 10.04 million in 2020, according to data from the country’s Ministry of Public Security, a record low in modern history.

“A better way to have handled the population growth [in the late 1970s] would have been to encourage people to have children at older ages and to space their children apart,” says Cody. “Everyone focuses on the extreme methods that were used to enforce the policy, but when demographers look at the numbers, they suggest that spacing could have been a more effective way at handling the population growth.”

Manpower vs. robot power

The economic boom of the last 40 years was originally based on low-labor costs with enormous numbers of migrant workers moving from rural areas to coastal factories. But now the improvement in living standards and the sharp changes in demographics are making it hard for manufacturers to find enough workers at the right price.

As of the fourth quarter of 2020, manufacturing-related positions accounted for 36—more than a third, of the 100 job categories with the greatest labor shortages in a list compiled by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. A report from Capital Economics said that the workforce is already shrinking by more than 0.5% a year, although that is, to some extent, offset by technology.

“Many jobs in the future will not require a human presence and will be substituted by artificial intelligence devices,” says Hansstein. “This could affect both the working and the middle class. With an aging population and informatics infrastructure development, who knows, the retirement age will be extended, and new age-specific jobs will emerge.”

A key part of the demographics problem is that China is not increasing its average productivity levels per worker fast enough to offset the demographic decline. One reason the country is investing so much in technology is because the government has realized they’re running out of time. The International Monetary Fund estimates that annual productivity growth averaged just 0.6% between 2012 and 2017, a sharp decline from an average of 3.5% in the previous five years.

“The key challenge is really about enhancing productivity for the younger people, and then instilling in them a work ethic as well as an economic or institutional framework of [how] a modern economy should run,” says Bassolino.

“China is facing a productivity crisis and continuing problems in investment funds in the most productive parts of society,” says Andrew Collier, managing director of Orient Capital Research, an independent research firm. “According to the World Bank, from 2015 to 2018, average GDP growth slowed, mainly because of a decline in productivity. The continuing injection of credit into infrastructure and the property market, along with support for state firms, has widened the gap in productivity. Relying on the property sector for GDP growth is an inefficient use of capital.”

China is investing heavily in industrial robots and artificial intelligence as a way of boosting productivity, and it already has both the world’s largest human labor force and robotic labor force. “Looking at the kind of investments that have been made in technology, China will be able to compensate for a lack of manpower with increased productivity. The robotic labor force also allows for lower maintenance costs,” says Sethi.

But automation only solves half of the problem—workers both produce and consume, while robots only produce. The migrant workers of the 1980s and 1990s and their children are today the mainstays of the domestic economy.

Let’s splurge!

Around the world, young people drive consumption. While the prospect of shrinking numbers of young people has an impact on the consumer spending outlook, that is offset by the fact that improved living standards and greater disposable incomes will allow them to spend more overall.

“The volume of consumption may suffer as a result of this demographic trend,” says Sethi. “But the consumption value will increase. People are increasingly going for premium, value-added and luxury products. So as long as incomes continue to rise, premiumization will compensate for the volume decline.”

Consumer spending is set to more than double in the next 10 years, with an emphasis on services rather than goods, Morgan Stanley analysts predicted in a report released in January. By 2030, consumer spending is set to reach $12.7 trillion, about the same that American consumers currently spend, the report said.

The aging population also presents new economic opportunities for health, property and consumer products aimed at old people, often referred to as the “silver economy.” “The elderly is a consumer segment with specific needs. They represent an exciting market opportunity for many companies,” says Hansstein. “The future focus might shift significantly, with diminishing importance of consumer segments like Generation X or millennials that were the main drivers of recent growth in consumption.”

4-2-1

One of the ironies of the demographic dilemma is that many young people now have six adults who will eventually pass on their net assets to the only child—two parents and two sets of grandparents. This has big implications for the property market. For most people, the most important asset is an apartment.

Property construction has been one of the main drivers of the economic boom in the past three decades and while vacancy rates in some cities are high, property values overall have skyrocketed. Urbanization is still powering ahead with the rate in 2020 being just over 60%, but the new generations coming into cities without the benefit of resident parents and grandparents are increasingly unable to own a home.

“It’s all about location,” says Bassolino. “The prime locations of Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen won’t be impacted at all because 1.4 billion people will all be vying for a spot there. For second and third-tier cities demand [for property] will decrease over time, because people are not going to want to live in those places anymore.”

Silver economy

The macroeconomic consequences of all these demographic and economic trends are potentially dire. The Ministry of Civil Affairs released a report in 2020 which said that by the end of 2019, 12.57% of the population was aged 65 or above, and that this demographic will reach 300 million during the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021-25)—meaning around 20% or so over 65. This has significant implications for pension arrangements.

“China’s economy is comprised of a lot more older people,” says Cody. “And many of them will be retiring in the next few years. It places enormous pressure on the country’s social welfare and health care system.”

The urban worker pension fund, the backbone of the country’s state pension system, held a reserve of RMB 4.8 trillion ($714 billion) at the end of 2018. It is forecast to peak at RMB 7 trillion in 2027, then drop steadily to zero by 2035, according to a report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

There are other societies around the world facing a demographic slowdown, but there are reasons why the crisis here is much more extreme. China’s slowdown was the result of a sudden government decision in 1978, whereas falls in birth rates and aging populations elsewhere including Western Europe, Japan and South Korea have been more gradual. Also, these regions have already achieved broad prosperity, while in China comparable levels of prosperity are still limited to a small proportion of the population.

“The demographic crisis here is even more of a problem than in places like Japan, because China has yet to successfully make it past the Middle-Income Trap,” says Bassolino. “The lack of liberalization of the economy in the last 15 years and the overall importance of control has created a situation where the economy can’t have the same level of dynamism to it. It’s a fairly pessimistic medium-term outlook.”

Many countries have dealt with demographic declines by resorting to immigration, especially Canada, Germany, the US and the UK. Even Japan has been somewhat more open to immigration in recent years. But China is unlikely to adopt this solution.

“Migration even within China is a challenge, with rural folk finding it difficult to obtain an urban hukou (household registration system),” says Sethi. “Migration from outside of the country at this stage is far-fetched. The government just doesn’t feel any need to do that and they would also then have to decide which ‘friendly’ nationals they could allow in.”

“I see it as highly unlikely that China will turn to immigration to solve this problem,” says Bassolino.

Little emperors still reign

With immigration off the table as a quick fix for the problem, the only alternative is the long game of encouraging couples to have more children. The current policy is limited to two, but there has been talk of removing all limits to the number of children couples may have. But it is not an easy sell to many young people.

During the years people were only allowed one child, they poured all their resources into ensuring the success of that child, making children’s education and grooming an expensive proposition. Those habits and ideas, honed over decades, have become norms, and it is unlikely that people will abandon them. For many people, the idea of a second child appears to be too much of a strain on already tight resources if they are to maintain the same standards in terms of education, child care and overall child development.

“Economically, it’s really expensive to have a child,” says Cody. “Especially in the tier-one cities and provincial capitals. Parents invest a huge amount of time and money into their children’s education.”

Bassolino agrees. “Having children is just too expensive. I also believe that a lot of people are now too self-centered.”

“Nowadays, the vast majority of parents are single children, they fear having more children because they do not have any comparison,” says Hansstein. “Another reason can be that many young professionals prefer investing in their career rather than family as a personal choice.”

Shifting Priorities

“The government has not been successful in convincing people to have more children,” adds Sethi. “What they need to do is to introduce more progressive policies and create a more encouraging environment. They need to give people the confidence that the future for their children will be good, that there will be employment for them when they grow up and to encourage women to return to the workforce after maternity leave.”

It is also widely believed that people have been so heavily socially conditioned to raise only one child that government urgings to be more productive are not going to work. A sizable proportion of women of child-bearing age today have careers and the trade-off between work and family presents a huge quandary. There have been government ad campaigns promoting matchmaking, and television spots featuring families today usually show two children, not one.

“My parents often ask me when I plan on getting married and having children,” says Zhang Yichen, a 28-year-old woman in Shanghai. “But I just want to focus on my career. Having children will mean less time for pursuing the things that I’m passionate about.”