Against the backdrop of the trade dispute with the United States and a slowing economy, China is opening up key sectors to foreign companies in the hopes of raising the possibility of further foreign investment

In late 2018, German carmaker BMW became the first foreign auto manufacturer to take control of its main joint venture in China after Beijing loosened corporate ownership rules. It was a milestone, given that foreign ownership of such ventures has been with few exceptions, capped at 50% ever since China started welcoming foreign investors in the early 1980s.

Similarly, in late 2019 German insurer Allianz received Chinese regulatory approval to commence operation of China’s first fully foreign-owned insurance holding company. And after decades of trying, in March 2020, two of the world’s biggest investment banks—Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley—were finally granted permission to take majority control of their local securities’ joint ventures. Morgan Stanley had held a 49% stake in Morgan Stanley Huaxin Securities and Goldman 33% of Goldman Sachs Gao Hua Securities, with both moving up to take 51% control.

The relaxation in ownership controls opens up wide new operational vistas for foreign companies operating in China and, as the government clearly hopes, raises the possibility of another influx of foreign investment funds into the huge and, in many ways, still attractive Chinese market.

“We are seeing a slow opening in key sectors, for example, in financial services and other advanced manufacturing like automotive, where foreign companies now have much more open access in terms of what services or products they can offer to the market and in terms of what a foreign company can wholly own,” says Ben Cavender, managing director of the Shanghai-based China Market Research Group (CMR).

China has been a huge magnet for foreign investment for the last four decades. The investment funds from overseas in manufacturing and more recently in services and other sectors has been fundamental in the growth of the Chinese economy to become what it is today, the second-largest in the world. But there have also been massive areas of disagreement and no-go zones, which have on the whole made China a very different place for foreign companies to do business compared to Chinese companies doing business in other territories, and most notably OECD countries.

Over the decades and in spite of the restrictions, foreign capital has flooded into China because of cheap labor costs, production efficiency and a huge local market. But for many reasons, including a slowing economy and rising labor costs, China has become less attractive in recent times. In the past couple of years the Chinese government has started to address the problem of slowing foreign investment by easing the restrictions placed on foreign companies.

A shifting scene?

A much-anticipated Foreign Investment Law (FIL) went into effect at the start of 2020, broadening market access and better protecting the rights and interests of foreign investors.

The FIL replaced three previous laws governing foreign businesses and foreign investments in China, and provides for greater protection as well as enhanced regulatory transparency. It also identifies more key industries, such as agriculture, manufacturing and technology, in which China further encourages foreign investment with preferential policies.

The new law was introduced at the height of the China-US trade war, in which the US side aggressively sought to discourage Foreign direct investment (FDI) into China. The FIL’s implementation also coincided with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has cast a cloud over the world’s economic prospects in at least the short to medium term.

“The Foreign Investment Law promotes the legitimate rights and interests of foreign investors, especially the protection of intellectual property rights, and solves the pain points that have long plagued foreign-funded enterprises with regulations,” said Zong Changqing, director of the Foreign Investment Department at Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), to Chinese TV network CGTN. “It will greatly enhance companies’ sense of gains.”

To strengthen China’s attractiveness as an FDI destination, the negative list of industries barred to foreign participation has also been shrinking in recent years, and foreign ownership restrictions in the financial services area in particular, have been reduced for asset management companies, banks, fund and futures companies and personal insurance and securities companies.

FDI into China in 2019 was up 5.8% year-on-year reaching RMB 941.5 billion ($137 billion), which was quite an achievement considering that global FDI flows recorded negative growth of 1% in the same period. Comparable figures for 2020 are not yet available, although a sharp drop is expected due to the virus.

FDI started edging its way into China in 1979, and by 2002 China had surpassed the US to become the world’s top FDI host. FDI has played a crucial role in China’s economic development and export success, with the Ministry of Commerce in 2010 reporting that foreign invested enterprises accounted for over half of China’s exports and imports, provided for 30% of Chinese industrial output, and generated 22% of industrial profits while employing only 10% of labor.

“China has become a very attractive market for foreign investors in the consumer-facing sectors, such as auto and financial services,” says Nick Marro, the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Hong Kong-based lead analyst on trade. “This has led to the current situation that no one can really afford not to be in China.”

Points for China

The original motivation behind the strict controls on foreign investment, implemented from the early days of China opening up, was for the government to maintain control of all key sectors of the economy. At the same time, the country would gain the benefits to be accrued from foreign companies operating in China without providing them with the same levels of ownership and freedom of action that are common in most OECD countries.

Fast forward 40 years after China officially opened up and many major sectors of the economy are still dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs). This is in spite of assurances provided at the time of China’s entry into the WTO in 2001

“China kept sectors dominated by SOEs closed, as in the early days were unable to compete against multinationals that had better access to resources and technology,” says Marro. “The main argument of opponents of economic liberalization—not only in China but anywhere in the world—is that if you liberalize, you destroy local jobs.”

“Nevertheless, there is still a lot of protection for SOEs in place as well as a big push toward China supporting the growth of Chinese businesses in key industries,” he adds.

A pressure pot

In many ways, the new legislation can be viewed less as Beijing wanting to loosen control over key sectors and more a reaction to economic frailties of the last 10 years. Between 2013 and 2017, FDI inflows into China fell steadily. In 2017 total FDI inflows stood at $168 billion, below 2008’s $172 billion. More importantly, China’s FDI inflows relative to its gross domestic product (GDP) have also been on a downward trend, from 6.2% in 1993 to 1.4% in 2017, the lowest level since 1991. This coincided with GDP growth slowing to 6.1% in 2019, the lowest rate China has booked since 1990.

“The costs for not liberalizing are rising for China, epitomized by the distortions of the demographic legacy of Beijing’s one-child policy, which has resulted in relatively few young people burdened with supporting a very large population of the elderly,” said Harry G. Broadman, Chair of the Emerging Markets Practice at Berkeley Research Group LLC and a former US Assistant Trade Representative.

“For an economy as large as China to ride the bicycle fast enough to not fall off requires freeing up the sectors that continue to be dominated by SOEs to provide room for private competitors, including foreign companies,” he added.

Similarly, Sara Hsu, CEO at China Rising Capital Forecast, warned that failing to liberalize further will ensure that China remains tied to a course of domestic-led development.

“With high levels of debt and few sources of new growth, China is in need of liberalizing further to get to the next stage of development,” Hsu says. “This will require higher incomes and greater employment in advanced service sector and manufacturing jobs,” she adds.

More recently, pressure on China to open its doors wider to FDI has built up as it has become clear that the China-US trade war has made Chinese goods exported to the US more expensive than goods from rival exporting countries, such as Vietnam, due to higher import tariffs.

The Bulletin of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in February 2020 flagged cases of the outward transfer of parts of the industrial chain, such as auto parts maker F-Tech switching production of brake pedals from its Wuhan plant to its plants in the Philippines.

The Bulletin warned that industries such as clothing and textiles that depend heavily on low-cost labor could accelerate their reallocation to low-income countries, while electrical and electronics equipment, transport equipment and other industries with low labor intensity and high technology density may easily return to developed economies.

“As COVID-19 shaves economic growth, the government is under pressure to get as much economic activity as possible, which means it will be easy on private sector business, be it foreign-owned or locally-owned,” predicts Renaud Anjoran, Partner of Shenzhen-based China Manufacturing Consultants.

“To get the export-engine running again, the government will be tempted to let the RMB depreciate, and it may double down on its policy to give more subsidies for R&D by companies in strategic sectors, be it foreign-owned or locally-owned,” he adds.

More work ahead

With all of the regulatory changes to foreign investment that have taken place, the European Chamber of Commerce’s Business Confidence Survey of 2019, said that a quarter of respondents felt more welcome at the time of survey than when they first entered the China market.

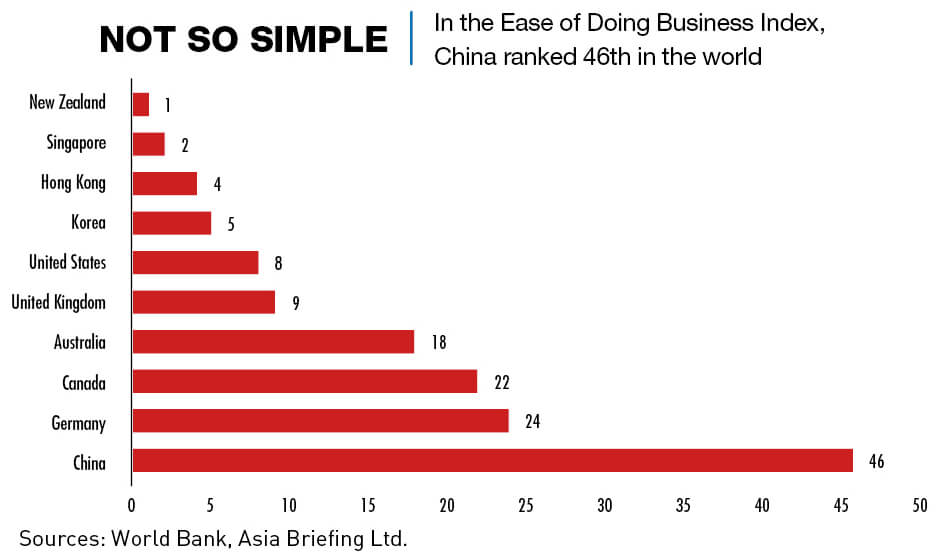

However, the same survey also pointed to foreign companies feeling an “us” and “them” attitude when it comes to how they are treated in comparison to Chinese companies. This is evident in how 15% of European Chamber of Commerce members also report that they continue to face direct market access barriers and 30% indicating that they face indirect market access barriers, such as complex administrative approval processes and difficulties accessing operating licenses.

“We see some positive aspects in the implementation regulations of the Foreign Investment Law, such as a stronger protection of Intellectual Property Rights and more restrictions on forced technology transfer, but we think that fundamentally, there should be no legal distinction between foreign and local companies except for legitimate reasons such as specific national security concerns,” says Carlo D’Andrea, Vice President and Shanghai Chapter Chairman of the European Chamber of Commerce.

“And while the 2019 Negative List revision brought openings in sectors like energy and oil and gas exploration and extraction, there appears to be little room for foreign investors in this already saturated market. As long as SOEs maintain a vertical monopoly on upstream, midstream and downstream industry, there is little room for outsiders to secure any more than a tiny fraction of the market share,” he adds.

A delayed win

China offers many advantages for foreign investment thanks to its huge market and the superb efficiency of its manufacturing ecosystem, but some people believe the era of mass investment into China is ending.

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to accelerate the diversification of multinational companies out of China to other regions, and with the many core economic building blocks already in place in China, there is less opportunity for new foreign investment in many areas of the market.

“It is probably too late for a lot of foreign businesses to take a leadership position in China as the market is too competitive. An example is the technology space where Alibaba and Tencent are probably too strong for American tech firms to compete with,” says CMR’s Cavender.

But the European Chamber of Commerce’s D’Andrea, thinks it is never too late for further liberalization.

He predicts that European companies will remain dedicated to China and understand the potential that has been hindered by various restrictions. “These enterprises will welcome liberalization with open arms and open check books.”