China’s massive anti-pollution campaign is driving thousands of factories out of business. But it’s also creating big new opportunities for green technology companies

Each spring, usually around mid-May, large parts of China’s third largest freshwater lake turn bright green. By the time the sweltering east China summer gets underway, thick, smelly clumps of algae are forming all over the surface of Lake Tai, the result of years of wanton pollution by the farms and factories lining its banks.

For the government of Wuxi, a city bordering Lake Tai, the arrival of the giant algal bloom every year is a nightmare. It impacts the revenues of local tourism sites and can even threaten the drinking water supply for millions of residents. But for Liu Bo, General Manager of Jiangsu Jinshan Environmental Protection Group, the return of the algae is a welcome sight.

Liu’s company has developed a method for turning Lake Tai’s pollution into piles of cash. Enormous filters stretched across five kilometers of the lake’s northern shallows hoover up thousands of tons of algae, which the company then dries and sells to Algix, a US-based business that processes the algae powder into bioplastics for use in everything from sneaker soles to yoga mats.

Jinshan earns RMB 300 ($45) from the Wuxi government for each ton of algae it collects and around RMB 800 ($120) per ton of powder from Algix, earning the company a 60% profit margin, according to Liu. “We expect to make a RMB 190 million [$28.7 million] profit this year and RMB 300 million next year,” he says.

The Wuxi company is an early mover in an enormous new sector emerging in the Chinese economy—environmental protection. China used to have a reputation for talking big but doing little on the environment, with officials focusing on economic growth above all else. But those days appear to be over. The government is pushing environmental protection to the very top of its policy agenda.

“When we’re talking about environmental protection now, it’s not only slogans—we’re also seeing real action,” says Song Shilei, a senior manager at “cleantech” solutions provider Evac.

In October during his address to the 19th Party Congress, Xi Jinping declared that the transition “from a phase of rapid growth to a stage of high-quality development” was the core of his vision for China. This shift in focus is likely to have far-reaching effects.

“The theme of development now is prioritized around increased demand for better quality of life and not just on speed of development,” says Li Yan, Deputy Program Director at Greenpeace East Asia. “That kind of top-down weight on key items in environmental protection is crucial.”

The Chinese government’s change in attitude threatens to disrupt a wide range of industries. “Companies in the West don’t really know this is going on, but China’s been shutting down 20,000 factories in the past year,” says John Pabon, Founder of sustainability consulting firm Fulcrum Asia. “Obviously that has huge implications for global supply chains because if you can’t have a stable supply chain in China, you can’t operate—it doesn’t work.”

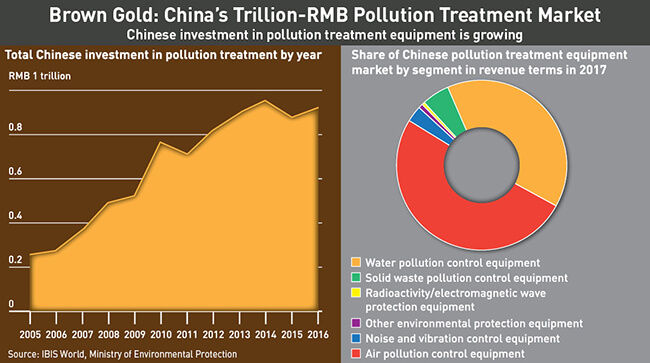

But it is also creating big new opportunities for cleantech companies with the government set to pour vast sums into its war on pollution. “During China’s 13th Five-year Plan (from 2016 to 2020), the Chinese government will invest at least $477 billion in environmental protection,” states Li Huihui, Analyst at research firm IBISWorld. “With strong government support, demand for pollution control equipment has large growth potential.”

Blind Development

Such jaw-dropping investment is understandable given the severity of China’s pollution problem. Decades of breakneck development have taken a terrible toll on the air, water and soil. By 2013, the average level of PM2.5 particles—a type of pollutant—in the air in China’s cities had risen to 60.5 micrograms per cubic meter, more than six times higher than the level recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Nearly 40% of the water in the country’s major rivers and 55% of its groundwater was unfit for human contact, a 2011 study by China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection found. Another government study in 2013 estimated that 20% of its agricultural land was contaminated.

The human cost of this pollution is equally severe. More than one million people in China die prematurely each year due to air pollution, according to the WHO. A further 60,000 are killed by diseases caused by water pollution, a 2007 World Bank report concluded.

For a long time, the central government made the right noises about fixing the problem, introducing a series of policies and targets, but for a variety of reasons the rules were rarely implemented at the local level. “The regulations have kind of always been there; enforcement is a totally different thing,” observes Pabon.

But, gradually, things have changed. A turning point came in 2014, when Premier Li Keqiang made a landmark speech criticizing China’s “blind development” and calling for the country to “declare war” on pollution. Since that point, in Pabon’s words, “there have been so many watershed moments… it’s hard to keep track of them all.”

“Environmental protection has been leading political rhetoric for the last decade, but in recent years it has turned toward a political agenda with real power and strong momentum,” agrees Greenpeace’s Li.

In 2015, the Environmental Protection Law was updated for the first time in 25 years to increase penalties for polluters and hold local governments more accountable for implementing the law. Even more importantly, according to Li, changes were made to the performance assessment system for government officials so that environmental governance “actually became central to their political careers.” The country’s environmental authorities have also been handed new powers giving them “more teeth to bite,” Li adds.

Flicking the Switch

Just how sharp these teeth have become can be seen from the stories of sudden crackdowns filtering through from different provinces across China in recent months.

“The government flicked the switch on this and said, ‘OK, now we’re going to enforce this,’” says Pabon. “It’s not a typical China cat-and-mouse game where the inspectors come in, we clean up what we’re doing, the inspectors leave, and we go back to normal. It’s the inspectors come, they read between the lines of what’s going on, they shut us down and we never reopen.”

One of the earliest examples of this new approach came in 2014, when Zhejiang, an eastern coastal province, shut down more than 21,000 of the 22,000 crystal glass workshops in Pujiang county for violating environmental regulations. Since then, similar campaigns have rolled out in other regions home to highly polluting industries.

“The government is doing it cleverly by implementing it step-by-step,” comments Yuval Ben-Sadeh, CEO of AST Clean Water Technologies. “They’re not destroying everything. They’re taking it region by region, and doing part of each region. It’s kind of a signal to the other regions: ‘Tomorrow we’ll be coming. Start to treat, start to do it now.’”

The message appears to be getting through. Debra Tan, Director of the non-profit group China Water Risk, has noticed a marked change in attitude among Chinese companies toward sustainability and corporate responsibility.

“Back in 2012, we faced skepticism that environmental regulations in China would impact businesses,” she says. “Today, it is a different story. Even Chinese banks like ICBC are taking the lead in assessing the impact of pollution regulations on their loan portfolios.”

A 2017 survey of 85 textile manufacturers in China by China Water Risk reported that 88% said they had upgraded their factories in the last two years to avoid shutdown. Companies that source materials from Chinese suppliers are feeling the impact.

“The price of packaging has increased over 100% because lots of cardboard manufacturers were shut down,” relates Ben-Sadeh. “It’s also affecting the coatings industry—the supply chain is being disrupted.”

New Horizons

But for cleantech companies, China’s new era of green-first policymaking promises a bonanza. The private sector will play a key role in China’s war against pollution, Pabon argues, as local governments search for solutions to their problems.

“The government will hand down a quota or some sort of regulation to the provinces, who will pass it down to the local leadership,” Pabon says. “But as you get down to a certain level, these government officials are not experts in that—they don’t know what to do. So that’s where the private sector comes in, as experts in particular areas.”

Private actors will also be essential because, despite the government already committing to spend $477 billion on tackling pollution by 2020, there is still a huge funding gap. The area where the disparity is most stark is soil pollution remediation.

“The cost of the clean-up is estimated to be $1.3 trillion,” shares Joe Zhang, a legal adviser at the International Institute for Sustainable Development. “But in the 12th Five-year Plan for Environmental Protection, only RMB 30 billion [$4.5 billion] was budgeted for soil remediation.”

Pollution treatment companies have started to fill this gap. The Chinese treatment equipment industry generated over $64 billion in revenue in 2017, estimates IBISWorld, a global market research firm. This is expected to rise to nearly $100 billion by 2022. The most lucrative market is currently air pollution control, which accounts for 50% of industry revenues, according to IBISWorld.

“Air pollution is the number one priority now, and that’s driven by massive public demand for clean air and for a healthy life,” states Li. The market is quite mature and competition is fierce, though Li notes that there is still plenty of room for growth since “people and governments in inland cities increasingly want this technology too.”

China’s battle against air pollution is also creating new markets for products aimed at both governments and consumers. The most famous example is air purifiers, which is now a $1.3 billion market in China and growing at around 10% per year, according to analysts Research & Markets. And consumers’ concerns about air quality have also created huge demand for new products, such as portable pollution monitors.

“Before 2014/2015, it was hard to imagine that portable air pollution monitors, for example, could be a new market,” says Li. “Our public wants air pollution monitors on their desks and that’s already a booming business.”

Tech companies, meanwhile, are gaining contracts with local governments across China to help them forecast spikes in air pollution. IBM has already announced a partnership with the northern city of Zhangjiakou—where the 2022 Winter Olympics will be held—to create an air quality modeling system. Microsoft has completed a deal with the Ministry of Environmental Protection thanks to its ability to provide 48-hour pollution forecasts.

In contrast to air pollution, the battles against water and soil pollution have barely begun. “In my industry, it will be booming, there’s no doubt,” shares Shi, whose company specializes in wastewater treatment systems.

There is huge potential for growth in water pollution solutions as only 3% of villages and townships in China have wastewater treatment facilities, according to Dezan Shira & Associates. Less than half the country’s industrial parks have centralized treatment plants, consultants Aranca also point out.

Local governments are building treatment facilities at a rapid rate, many of which are financed by public-private partnerships (PPP), Aranca notes. More than RMB 3 trillion ($450 billion) worth of PPP deals were signed in China during the first nine months of 2017 alone.

The soil pollution solutions market is even less developed. “Soil remediation is a goldmine, but it’s not clear who has the tools to dig it,” says Li.

The government is determined to detoxify agricultural and brownfield land, and has published at least eight policy documents since 2008 attempting to address the issue. But progress remains slow due to lack of funding and the high cost of current remediation solutions.

“Restoration at this stage is still super expensive,” says Li. “So, any innovation… would be critical to solving the bigger problem.” Companies able to develop low-cost solutions are likely to find big opportunities.

If You Can’t Beat Them…

For foreign companies, however, taking advantage of these opportunities requires a realistic mindset, Ben-Sadeh insists. “It’s still a game for the big environmental Chinese companies, not so much small private companies,” he says. “At the end of the day, the big industries tend to work with the big Chinese companies.”

Contracts for large projects such as centralized waste treatment plants tend to go to large industrial groups like China Tianhao Group and China Datang Corporation, which have good connections and huge resources. For Ben-Sadeh, the key is not to compete with these companies, but find ways to work with them. “The foreign companies generally cannot be the main contractor. They can be the service provider, they can provide part of the solution,” he argues.

Cooperating with Chinese partners is likely to become even more important in the future as the government may tighten restrictions on the use of foreign technology in strategic sectors. The State Council, China’s cabinet, has already set a target that 70% of equipment used in desalination plants should be made in China, for example, and similar rules are gradually starting to be introduced in the wastewater treatment industry, according to Evac’s Shi.

“That’s in fact a topic we are currently talking about because we’re working on a huge project where the customer has said that no 100% foreign company can sell to this project,” reveals Shi. About 20% of Evac’s projects in China are affected by this kind of rule, he estimates.

“We can still find a way to do this project, because we have reliable partners and reliable suppliers in China,” Shi adds. “We can provide our systems to them, it just needs to be manufactured in a different way.”

In some cases, the requirement to source equipment in China may not turn out to be harmful to some foreign companies, according to Ben-Sadeh. “My ability to compete has become better,” he says. “When I first came to China, I couldn’t trust the local products. I had to bring it

[equipment] because it was better quality. Today, on the contrary, it’s class-A production with a competitive price.”

But this improvement in standards in China has a downside for foreign cleantech players—domestic rivals are providing a much fiercer challenge. “Ten years ago, foreign companies made fortunes here. Today, they have huge competition from local challengers,” says Ben-Sadeh.

Overseas companies will need to up their game to find success in this new era. According to Ben-Sadeh, the key will be to “analyze and understand what are really the needs of the market” and to “keep in front in technology,” even if the parts must be manufactured on the Chinese mainland. Doing so will be a big challenge, but the potential rewards promise to be even greater.