China’s fourth-tier consumer markets come into their own.

Taixing is still, by Chinese standards, a small community–in the downtown area, there is only one building over 10 stories, automobiles are easily outnumbered by two-wheelers, and one sign outside a clothing store offers “All outfits 9.90 yuan!” (around $1.50). Yet on the same downtown block is another KFC and three retailers displaying large Apple logos.

This penetration of the big wide world and its powerful brands into China’s interior has occurred with phenomenal speed. “The KFCs and all three ‘Apple’ stores showed up just this year,” says Yusha, a 42-year-old saleswoman working at a cell phone outlet in a small nearby mini-mall.

Big Brands, Big Journey

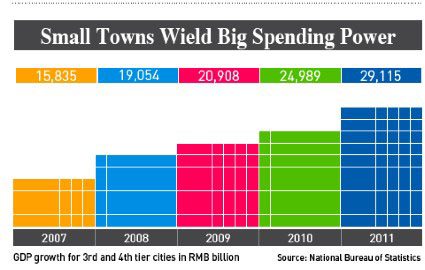

The Taixing experience is being repeated in countless fourth-tier and county-level cities around China, officially defined by the level of government overseeing these cities, which is the county or prefecture government. The average annual income in the county-level cities in 2011 was around RMB 27,000, and has risen consistently over the past two decades. More and more national Chinese and international brands are laying the groundwork in what they have identified as a massive market. Retail sales of consumer goods at and below county level totaled RMB 1.74 trillion between January and August 2012, up 14.3% year on year. The market research firm Neilsen estimates lower-tier cities account for 64% of retail sales.

The expansion trend encompasses all sectors. Home Inns, owner of the successful Motel 168 brand, opened around 280 new hotels in 2011, around half of them in third and fourth-tier cities. In clothing, Chinese brand Yishion, scarce in upper-tier cities, anticipates earnings of RMB 8 billion in 2012 mostly from its smaller town stores, while French brand Cache Cache, which has opened 500 stores since 2005, has also largely ignored tier-one markets in its expansion plans.

Luxury products are also seeing growth in the remote interior cities and towns, especially automobiles. BMW sales in fourth- or fifth-tier cities grew by 50% year-on-year in the first seven months of 2012 according to company data. The German brand had stores in 290 locations across China in 2011, and planned to open 30 new stores in 2012. Volvo, similarly, has announced plans to expand from 109 to 250 dealerships over the next five years, most of them in third- or fourth-tier cities.

She Duanzhi, Vice-President of Dutch appliance maker Philips China, told CKGSB Magazine that the company’s new moderately priced line of home appliances was aimed squarely at this market. “It’s part of our tier expansion strategy,” She says.

Philips analyzes a variety of indicators for different cities, She says, including GDP and amount of disposable income, to determine the appropriate strategy for each place. “There’s a concern that the tier-one mega-cities are slowing down in terms of consumption and growth. In contrast, in inland provinces, and tier-three and four cities in particular, consumer purchasing power and incomes are growing very fast.”

Ready to Shop

While older fourth-tier consumers are generally price conscious and more comfortable with local brands, the younger generation is different. For them, the popularity and status of large, global brands is becoming more and more an attractive investment. “Foreign brands are fashionable,” says Jenny, a 23-year-old woman using an iPhone, who declined to give her surname. “And their quality is high too.”

“In China, the generation gaps are huge,” says Alan MacCharles, partner and China market consultant at the accounting and consultancy firm, Deloitte, adding that the younger generation spends a much higher percentage of their income and has a different approach to valuing products.

“They’re now looking to show off their new wealth,” Chris Devonshire-Ellis, founder of market entry consulting firm Dezan Shira, told CKGSB Magazine, explaining that rising wages and government subsidies for some consumer products are major factors.

Part of the draw of bigger brands is that more and more fourth-tier youths have spent time studying, working, and traveling to the coastal metropolises. “I’m definitely influenced by what’s going on in bigger cities, since I studied in Nanjing and have spent time in Shanghai and Hangzhou,” says Jenny.

The result is that younger fourth-tier consumers are close in their buying habits and choices to their first-tier counterparts. But a 42-year-old worker at the Taixing bus station, Wang Hong, says that young people all over are much the same: “They all love what’s fashionable.”

Reaching the Consumer

The rise in demand from young smaller city consumers speaks of greater opportunity for brands currently established in large coastal cities. The next step for them is to devise a marketing approach that reaches consumers on both sides of the generation gap.

The most important considerations for brands looking to enter these smaller markets are price and utility. “Our tastes aren’t like those of people in Shanghai,” says Wang Hong at the Taixing bus station. “We pay attention to practicality. They can afford to be extravagant.”

According to a 2009 survey conducted by Deloitte, 45% of respondents in the fourth-tier cities of Changshu, Jiangsu and Xinmin, Liaoning, purchased shoes for less than RMB 300 a pair, compared to 37% in Shanghai. Meanwhile, less than 20% of Changshu and Xinmin residents owned international-brand shoes, next to 35% in Shanghai.

“I wouldn’t buy anything just because it’s an elite brand,” says Yusha. “Buying something to gain face is foolish.”

T.B. Song, Chairman of advertising and marketing firm Ogilvy & Mather China, cites Nike and Adidas as two companies that could benefit from focusing efforts in the fourth-tier for their low-end products. “Product is not the issue,” he says. “I think price is the issue.”

Deloitte’s MacCharles names apparel and electronics as examples of sectors where tier four residents desire similar products to consumers elsewhere, but insist on paying less.

“In apparel, they want comfort, brand, value for money–the same things everyone wants. They don’t even buy that many fewer units, they just spend less. Then, in electronics, it’s just getting the most you can for the price. So international brands sell fewer than domestic brands, which are feature-laden and cheap,” says MacCharles.

Price sensitivity is an issue well heeded by many large Chinese brands. Chinese computer maker Lenovo, for instance, had found great success targeting smaller markets with a computer that sells for only RMB 1,499.

Philips’ cheaper line of home appliances includes a rechargeable RMB 99 razor, a product Philips has never before sold for less than RMB 200. In a nod to penny-pinching practicality, Phillips also advertises a toothbrush that requires no toothpaste. “In general, people want to use branded products but they can’t afford high prices,” says Philips’ She.

It’s the Journey that Counts

There is more to entering the fourth-tier than coming up with the right product and the right price. One of the biggest challenges that food and beverage companies must overcome if they want to expand into this growth market is logistics, particularly cold-chain logistics and storage.

Devonshire-Ellis points to the difficulty of shipping products to the city of Changxing in Zhejiang Province as an example of the difficulty of setting up shop in these markets.

“Changxing relies on transportation along the Yangtze River. The problem is that the port operators are state-owned and they do not welcome competition. So the result is a really, horrendously inefficient service getting goods into and out of [the city]–because they’re state-owned and don’t really care–at extremely high prices,” he says. “The central and western parts of China in terms of infrastructure, politics, and commercial mindset, are about 10 to 15 years behind the East coast.”

One way to make products widely available despite remote locations and a lack of infrastructure is to use third-party distributors that already have local stores and logistics in place. Such outfits can bridge the gap for companies with limited resources aiming to sell directly to local markets. Sports apparel firms like Li Ning, Anta, and 361 have all found success with this model. “They’ve done surprisingly well,” says MacCharles. “When you go down the main street in a lower-tier city you tend to see big sportswear brands and a lot of those are distributor stores.”

Chinese brand Ming Le is one such company. The sportswear brand uses 24 different distributors to reach over 3,324 retail outlets in China, approximately 87% of which are located in more than 1,000 tier three and four cities.

The trade-off with such a model for larger companies is that they are typically unable to access detailed information on what is being sold where and how much inventory is being held, which hinders efficiency. “Someone else deals with how to position you and where to position you locally, so you’ve got less control,” says MacCharles. “It’s a question of how much you’re willing to let go.”

For companies determined to maintain control, the cost of setting up one’s own distribution network may be astronomical, but so may be the eventual profits. Chinese appliance maker Haier set up a subsidiary Ririshun in 2003 to handle distribution and franchise stores in tier-three, tier-four, and rural areas and the company quickly expanded to handle distribution and retailing for competitors as well, and in 2009 reached revenues of RMB 45 billion.

In cases where it’s not feasible to carve out a physical presence, consumers can now be reached through e-commerce. Internet usage is now common in all corners of the country. “It’s not a lower-tier or upper-tier thing–everyone’s online,” says MacCharles. “Particularly people with the money to buy your products.”

“There aren’t many places to shop in Taixing and you can’t expect to find every brand, so I shop online a lot,” says Jenny.

Hancao, a herbal cigarette maker that relies largely on the appeal of its Chinese medicine ingredients, has had success in lower-tier markets using third-party regional distributors. But it also operates a flagship store on Taobao.com, China’s largest consumer-to-consumer website.

Building Awareness

The problem of building brand awareness in China’s interior is well illustrated by Deloitte’s 2009 survey, which found that 38% of those surveyed in fourth-tier Changhshu and Xinmin thought Nike and Adidas were domestic brands. What’s more, people who grew up before Western brands began to exert their current influence in the market often find many of the brands intimidating.

Taixing’s Kuang Meiying, 34, says she strongly prefers local brands. “It’s not just that Chinese brands are cheaper. I can’t make sense of foreign brands.”

“It’s been [decades] since most brands began arriving in Shanghai, so consumers have had some time to absorb them and what values they represent,” says MacCharles. “In fourth tier cities, brands have only been getting there recently.”

One way of increasing familiarity with your product is through local sales events, which tend to have much greater impact for the marketing outlay than in the coastal cities. “Sales events are more effective in fourth-tier cities because they haven’t had a chance to experience the product before,” says Song.

He points to P&G as a successful example. “They do product tests in small cities and the sales lady explains the product to consumers. They’ve already been doing these sorts of events in smaller cities for three or four years. Partially because of this, most P&G brands are quite successful in third- and fourth-tier cities, especially shampoo.”

The Internet, meanwhile, is proving useful in terms of awareness as well as availability. Philips’ She Duanzhi emphasizes the importance of online promotional events and agreements with e-commerce websites to support Philips lower-tier strategy. “We have very good collaboration agreements with e-commerce players like Jingdong and we do promotions on there from time to time.”

A Limitless Future

Ultimately, while China’s fourth-tier market can be a tough nut to crack, the future will be even tougher for companies that decide to shy away from the challenge now.

“If you are content to stay in Shanghai, ultimately you will face increased competition,” says Devonshire-Ellis. “If you get out into the fourth-tier cities, there is less competition. It’s tougher, but it’s an ‘early bird catches the worm’ scenario.”

Besides rising incomes, growing urbanization is also a factor. China’s urban population topped 50% for the first time this year, and the consulting firm McKinsey predicts that China’s cities will be home to more than 1 billion people by 2030. Much of that growth in urban residents will occur in the third- and fourth-tier cities.

“In the near future, maybe 80% of Chinese will live in cities,” says Song. “And fourth-tier cities will become third-tier cities, while third tier cities become second tier cities.”

(Image courtesy Flickr user Bert van Dijk’s photostream)