China’s space program is still far behind that of the United States, but it has fast caught up with other nations. The implications of China’s presence in space are far-reaching, in terms of economics, technology and the military

When the 2,600-pound goddess of the moon finally let her jade rabbit out, it first turned a victory circle on the powdery lunar regolith before trundling away. The goddess was Chang’e 3 (from Chinese mythology), an unmanned lunar lander, and the jade rabbit was Yutu, a lunar rover. The day was December 14, 2013, and as Chang’e 3 touched gingerly down, it marked the first soft landing on the moon in almost four decades—and a milestone in the development of China’s growing space power.

In an age when governments and private companies alike are set on human exploration of Mars, another moon landing may seem like back-page news. China, however, has long viewed its space program as important to bolstering national prestige and influence, boosting national defense, and promoting domestic industries and economic realignment.

“Exploring the vast universe, developing space programs and becoming an aerospace power have always been the dream we’ve been striving for,” President Xi Jinping said on China’s first Space Day on April 24, 2016. That date was the anniversary of the launch of China’s first satellite, the Dong Fang Hong I (The East is Red I), which reached orbit in 1970.

Beijing arrived late to the final frontier, but is making ambitious efforts to catch up. By 2018, it aims to send a probe to the dark side of the moon—the first-ever such trip—and to put astronauts on the moon by 2036.

While space may be the most difficult environment to conquer, the challenges are not only technical. China must compete against more established players, allay international security fears, as well as balance the considerable cost of a space program against other considerations, such as public opinion concerned about a slowing economy.

Looking to the Stars

China’s celestial endeavors date back seven decades. In 1956, China developed its first rocket and missile research institute—two years before the creation of NASA. In the early years of the People’s Republic, China’s space program was given significant support by Mao Zedong, who saw it largely as a military undertaking.

Chinese engineer Qian Xuesen was known as the “Father of Chinese Rocketry.” He studied in the United States in 1935 and was later recruited to Caltech where he worked on developments that included the founding of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. When he returned home in 1955, he helped lead a nuclear weapons program that led to China’s first successful atomic bomb and hydrogen bomb tests. He also headed China’s ballistic missile program, and then, naturally, the early Chinese space program.

Despite this early start, China’s focus on space lapsed during the following decades of turmoil. It wasn’t until the 1990s that China’s space program began to accelerate. In 2003, China became the third country to put a man in space with its own rocket (after the Soviet Union and the US). In 2008, Chinese astronauts made the country’s first spacewalk—and momentum has been growing ever since.

“The space-science program in China is extremely dynamic and innovative,” Johann-Dietrich Wörner, Director General of the European Space Agency (ESA) said recently at a Paris meeting. “It’s at the forefront of scientific discovery.”

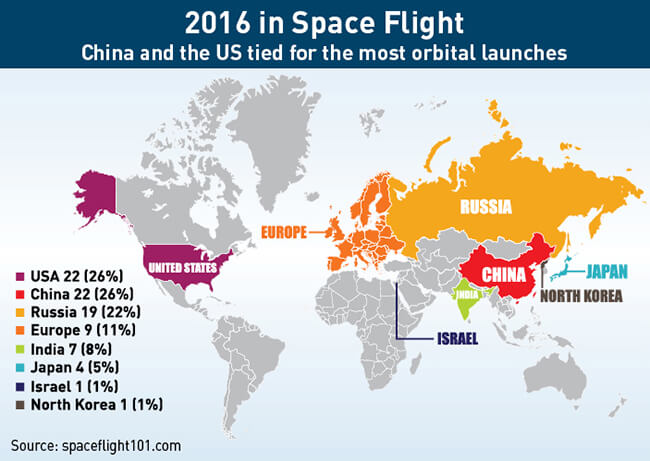

Today, China has more than 100 satellites in space, launched mostly from locations in the south of the country, including the newly-built Wenchang Satellite Launch Centre on Hainan Island. Its most recent successful launches include the Long March 7 rocket last July. In 2016, it conducted a total of 22 space missions, tying with United States for the country with the most launches.

“China’s success is in laying out a long-range plan and sticking to it,” says John Logsdon, Professor Emeritus of Political Science and International Affairs at the George Washington University. “China’s various Five-Year Plans for its space program have been made public and executed. It’s about having a long-range vision that space is an important area of competence and capabilities, and step-by-step developing world-class technologies and capabilities.”

Long-term planning was evident in April when Tianzhou-1, China’s biggest and heaviest spaceship to date, was launched. It docked with the Tiangong II space lab, launched last September, and conducted in-orbit refueling—a challenge at the edge of technical capacities in space. While the Soviet Union was the first to pull off docking between unmanned ships in 1967, in-orbit refueling is an engineering feat that has only been completed a handful of times.

The launch of Tianzhou-1 is a crucial step towards two of Beijing’s most important goals: to send a rover to Mars by 2020 and to launch and resupply a manned space station by 2022. China is also testing the ability of astronauts to stay on the moon for extended periods. A current experiment has volunteers live in a “simulated space cabin” for 200 days at a time, helping scientists understand what is needed for humans to remain on the moon for long periods.

Power Vacuum

Space programs have always been closely linked with international relations, defense and military goals, and China is no exception. China’s answer to NASA is the state-run China National Space Administration (CNSA), established in 1993, which holds responsibility for planning and developing space activities.

Tian Yulong, CNSA’s Secretary General, told an international conference in April that China has signed more than 100 space-cooperation agreements with 30 countries and space agencies. But even with this international collaboration, China has had to develop its own domestic talent from scratch, with the talent pipeline centered on the prestigious Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

“The failure of groups like NASA to work with China has to some extent incentivized and motivated China to do more themselves on growing talent, as a matter of domestic pride and sustainability,” says Richard Suttmeier, an expert in China’s science policy.

China has also been an enthusiastic participant in international training programs, including a nine-week summer program run by the International Space University.

“The summer program brings together people from around 26 different countries for an intensive program on all aspects of space,” says Logsdon, “China has been the largest participant for the last ten years. Of the 120 people there this year, 25 are Chinese. Sending people for that kind of training is just one example of China’s focus on developing human capabilities.”

China is also a member of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space and the UN Platform for Space-based Information for Disaster Management. For many decades, however, China’s space program has raised suspicions because of its military links.

“China’s space capabilities are closely linked to its military,” says Dean Cheng, Senior Research Fellow at The Heritage Foundation. “The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) is in overall charge of China’s space industries, which are all state-owned enterprises. MIIT is also in charge of the defense industrial complex. China’s space launch facilities are also all run by the military.”

This has made some international agencies wary of working too closely with Beijing. Others fear China might allow its space program to be used by countries with more aggressive purposes.

“The major concern is that China [could] become a country supporting things like missile development in places like North Korea and Iran,” says Denis Simon, Executive Vice Chancellor of Duke Kunshan University, and an expert on Chinese science policy. “The more China becomes embedded in the larger fabric of the global space industry, the more responsibility China has to take for being cautious and vigilant that its technologies do not get used for nefarious purposes.”

Earthly Challenges

Even with the rapid pace of advancement in China, conquering space is no mean feat—it is fraught with danger, both technical and political, and failures are inevitable. Last July, China’s launch of its new heavy-lift rocket, the Long March-5 Y2, failed while carrying its heaviest-ever satellite. This failure could delay future projects, such as the planned rover flight to the far side of the moon in 2018.

However, Denis Simon estimates the Chinese have a 97% success rate with rocket launches, which is a very low rate of failure. And there are huge gains in prospect. China’s manned space station, if launched as planned in 2022, could potentially become the only one in orbit, as the International Space Station approaches the end of its planned service life.

“If the International Space Station is de-orbited in 2024, and there is no replacement, then it is likely that China’s space station, scheduled for launch around 2020, would be the only space station,” says Cheng, although experts disagree on the likelihood of this scenario due to political tensions.

Because of the global security concerns that have dogged China’s space program, the country has had to build up much of its knowledge domestically, as countries like the US were unwilling to allow access to its own research. US suspicion of China dates to the work of the Cox Committee, which concluded in the 1998 that China “has stolen or otherwise illegally obtained US missile and space technology that improves PRC military and intelligence capabilities.”

Although China has denied the claims, and nobody has ever been convicted, this thinking has influenced China-US scientific collaboration for decades.

“It hasn’t been easy for China, which has faced issues about access to technology because of the close linkage between the civilian space and military space programs,” says Simon. “Access to foreign technology has been difficult… China has done a great deal through self-reliance and through indigenous innovation.”

Simon continues: “It is only recently that space collaboration has picked up with the US, and it’s done so with a great deal of caution. So, China has worked with a number of other countries and the European Space Agency to jointly advance and develop their space capabilities.”

Indeed, the CNSA has ramped up space-science efforts and collaborative projects, including a pioneering $440m X-ray telescope, which is planned for launch by 2025. The mission is financed with European partners and involves hundreds of scientists from 20 countries, preparing to study matter under extreme conditions that can be found only in space.

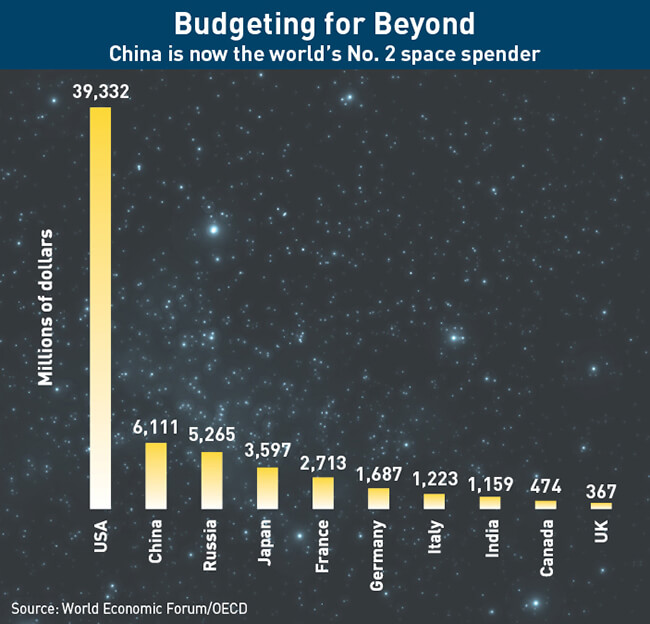

China also faces significant competition from rivals in the development of space technology, particularly from neighboring India. Already a space power, India launched a satellite into orbit around Mars in 2014, the only country to do so on the first attempt. Meanwhile, Russia is still the only nation that can regularly launch humans into space and bring them back, sending about four crews every year to the International Space Station. But at $6.1 billion in 2013, China’s financial commitment is larger than that of India, Russia and Japan individually—although that is still well behind NASA’s 2013 budget of $16.8 billion.

Private Space

President Xi hopes the space missions will fuel a wave of Chinese innovation in robotics, aviation, astronautics and AI to help boost the economy. The state is also providing support for the emerging private space sector. Although there are only around a dozen commercial space enterprises in the country, the nascent sector has attracted significant investment.

In May, rocket design startup One Space Technology announced that, months after completing its A-round of financing last year, it had secured an unspecified amount from Chongqing Two Rivers Aviation Industry Investment Group. Weeks earlier, the Tianyi Space Research Institute announced that it had raised close to RMB 100 million ($15.3 million) in its own round of financing.

Another major player is Kuang-Chi Science, led by Liu Ruopeng, the “Elon Musk of China.” His company is developing cutting-edge aerospace technology, including a balloon-launched capsule called The Traveler, which aims to take six passengers as high as 100 kilometers above earth. It has performed two test launches since 2015, the second of which safely carried a live turtle.

Even Chinese social media giant Tencent is looking beyond Earth. It is investing in America’s Moon Express, a startup that aims to put drones on the moon; Argentina’s Satellogic, which specializes in satellite imagery; and America’s Planetary Resources, which is examining asteroid-mining.

Chang Guang Satellite Technology, founded two years ago by more than 40 institutional and private investors with technical support from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, is one of many micro-satellite and nano-satellite assembly plants to have emerged. Each has plans to send small satellites into space. Chang Guang aims to launch 60 satellites by 2020.

China’s BeiDou Navigation Satellite System, the country’s answer to GPS, is another motivation for China’s space research. The system, already covering 317 Chinese cities, is eventually intended to cover the globe, especially countries tied to the Belt and Road Initiative. By 2020, thirty-five satellites should be operational. Businesses related to BeiDou are expected to be worth $58.1 billion by 2020, said Ran Chengqi from Beidou Navigation Satellite System, speaking at a conference in May this year.

But while investors seem optimistic, China has a long way before its commercial space industry catches up with the likes of Elon Musk. His SpaceX is leading the way in private rocket launches—including deliveries to the International Space Station—and making strides toward reusable rockets and manned missions.

With the economic boom of recent decades fading, Beijing recently set its 2017 national GDP growth target at 6.5%, the lowest in 25 years. Some experts are concerned that funding might slow further as other priorities compete for attention.

“It may be that Chinese leaders will feel that the investments are higher than justified,” says Dean Cheng. “Alternatively, as a means of moving the Chinese economy up the value chain, fostering advanced technologies and indigenous innovation, and improving productivity, space may be seen as a means of improving Chinese economic growth and performance.”

For the time being, China remains a relatively small player in the satellite industry. But experts say the country could easily catch up in numerical terms because it is building satellites more cheaply, although it is not yet clear if China’s private space companies are making money.

To Infinity

In space terms, China is still behind Western governments and private companies like SpaceX, and the future promises more jockeying between rival nations. The international space market looks set to be dominated by extremely fierce competition as China continues its huge investment into space-science, satellite and navigation technologies. And apart from rivalry over scientific achievement, China’s space program will continue to cause security jitters between China and other nations.

But, China intends to be a major player in space and, with a strong and growing domestic talent pipeline, Beijing’s power in the heavens only seems set to grow. In twenty years, the world could be watching China land its first astronauts on the moon—just as planned.