As China changes, companies are being forced to adopt China Plus One strategies and look at other countries for manufacturing.

Since opening up to the world in the late 1970s, China has transformed itself into the worldʼs leading manufacturer, a veritable global workshop. But ʻmade in Chinaʼ isnʼt always what you see on labels anymore. Instead, other Asian countries are increasingly fighting to be the makers of the worldʼs consumer goods, and this shift reflects broader changes in China that have significant implications for its role in the global economy.

This is the world of China Plus One in which manufacturing capacity is not necessarily moved, but diversified beyond China, usually to countries in Southeast Asia. The idea had been discussed and inconsistently implemented by manufacturers for years, but China has now reached a point where, for many business leaders, diversification is no longer just something to conjecture about over dinner. Instead, China Plus One has moved to the top of the list of strategies, with Intel, Samsung, Nike, Foxconn and a range of Japanese companies including Canon all having pursued the idea to various extents.

“A China Plus One, or China Plus Two strategy is definitely an essential component of any large brand-buying operation due to rising labor costs and shortages in China,” said Judith Mackay, Asia Apparel and License Compliance Manager at New Balance, when commenting on the idea to Bloomberg.

A Changing China

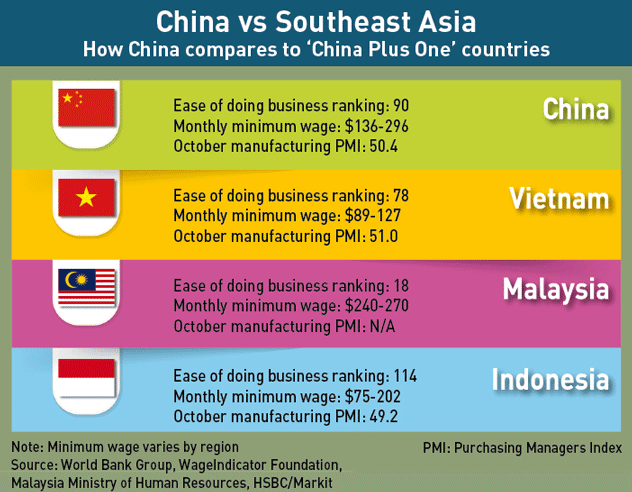

This trend is being driven by many factors, but the main reason is higher labor costs, with wages having risen significantly in the past few years, particularly in the coastal regions that have long served as Chinaʼs manufacturing hubs. A Standard Chartered report based on a survey of non-mainland manufacturers operating in the Pearl River Delta predicted wages in the region would rise 9.2% in 2014, having increased 8.4% in 2013.

Underlying the increasing labor costs are two factors—changes in population and shifts in government strategies.

China is getting older—the workers that have powered its economic growth are nearing retirement age, and the so-called one child policy means that they wonʼt all be replaced. In 2013, the working age population decreased by 2.4 million according to Chinaʼs National Bureau of Statistics, the second year in a row that the total workforce declined. As workers become scarcer, those left are in a position to ask for more.

The other factor underlying rising labor costs is the governmentʼs desire to shift China towards a consumption-oriented economy. Wages in many regions are constantly nudged higher by local governments increasing the minimum wage.

Financial pressures arenʼt just limited to wages—higher real estate and compliance costs have also played a role.

But beyond a desire to keep costs down, the China Plus One strategies of manufacturing companies are increasingly being driven by other factors, particularly risk diversification and the awareness that there are other markets to address beyond China.

“Companies are much more conscious about trying to have robust supply chains in which you can continue production even if your principal site of business is facing some difficulties,” says Peter Petri, the Carl Shapiro Professor of International Finance at Brandeis University. “You want to have a geographically diverse supply base, you want to have access to markets in many countries and you want to protect yourself against a wide range of risks.”

Added to this is the recognition of the development of Asia as a whole—the growth of a middle class in many Asian countries, and thus a growing body of consumers, which makes having a manufacturing presence in those places a much more sensible idea.

For some foreign companies, it can also come down to simply being made to feel welcome. Some Southeast Asian countries have also been rolling out the red carpet for foreign businesses, offering incentives and competitive tax rates. This has come just as the business environment in China has become more challenging for many foreign companies, with labor strikes increasingly common and a new government that some have claimed are targeting selected foreign companies on antitrust grounds.

“A lot of people are sick to death of China, and angry at China, and feel like they canʼt get a fair shake, and feel like theyʼre not really wanted there anymore,” says Dan Harris, a partner and founder of Harris & Moure, a law firm with years of experience in China, and co-author of the widely respected China Law Blog.

The shift towards the adoption of a China Plus One strategy is not necessarily limited exclusively to manufacturers. According to Chris Devonshire-Ellis, founder of Dezan Shira & Associates, a specialist in foreign direct investment practices, the trend applies to all companies in China, even service companies such as sourcing entities. “Itʼs not just a handful of companies or a niche,” he says.

Alternatives to China?

An indicator of this growing interest in Southeast Asia is the fact that in 2013 foreign direct investment into the ASEAN-5 (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand) outstripped FDI into China, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch. It has happened before, but the difference was more substantial than previously. This statistic cannot be taken as ultimate proof—the bulk of the money was flowing into Singapore, not a China Plus One destination—but it is still indicative of an overall trend. In addition to the leading ASEAN countries, Cambodia, Bangladesh and, less credibly, Myanmar are also touted as China Plus One candidates.

But the country most often put forward as the alternative to China as a manufacturing base is Vietnam. Intel, Samsung and Nike and other multinational manufacturers have expanded into the country in recent years, attracted by the much cheaper labor on offer there, as well as attractive tax incentives. Intel spent $1 billion on its Ho Chi Minh City facility and has committed another $21 million to high-level workforce training, while Samsungʼs $2 billion factory in the north of the country was granted four tax-free years (the following 12 are half price). In addition, Vietnam has stated that it will reduce its basic corporate tax rate to 20% by 2016, five points lower than Chinaʼs.

A quick glance at your clothes might reveal the growing preference of garment manufacturers for Vietnam, but the presence of giants like Intel and Samsung attests to its appeal far beyond the cheap labor costs always sought by textile makers. The Vietnamese government is very consciously targeting companies in the high-tech sector with its IT Master Plan, which aims to improve infrastructure and help the country meet international standards. Vietnam also appeals to companies because of its growing consumer market (the country has a population of 90 million) and its geographical position close to global supply chains.

Other countries have their own strengths too and each place has advantages that appeal to different industries contemplating China Plus One. Peter Petri cites the strength of Thailandʼs automobile-related supply chains and expertise, and Indonesia for its rich natural resources as industry-specific strengths of the two countries. “The important point is that in several Southeast Asian countries there is now very good local industrial infrastructure with which you can work to make this happen,” he says.

But China Plus One strategies are at this point mainly the preserve of large multinationals and are much harder to implement for small and medium-sized enterprises because they donʼt have the same level of resources to call upon when contending with the challenges that undoubtedly remain in these China Plus One countries.

Southeast Asian countries have also benefited from the development of new trade agreements in recent years. One of these is the ASEAN-China free-trade agreement, which reduces tariffs on 90% of imported goods, although not all countries are compliant—the remaining ones, including Vietnam, are expected to be by the end of 2015. This will have the effect of opening up the China market to manufacturers looking to access consumers there, while still allowing them to take advantage of what the Southeast Asian countries have to offer.

“[The ASEAN-China free-trade agreement] will have a significant impact on the relocation of light manufacturing destined for the China market,” says Chris Devonshire-Ellis.

However, the ASEAN-China trade agreement is viewed by some as quite a modest step, and not necessarily the key driver for businesses weighing up China Plus One strategies. “Although it probably helps to smooth some of the linkages between China and ASEAN so that you could divide your supply chain a bit more comfortably… itʼs not an especially ambitious agreement,” says Petri.

Perhaps of greater importance is the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a proposed US-led free-trade agreement in the Asia-Pacific region, for which both Vietnam and Malaysia have participated in negotiations and which China has been excluded from. According to Petri, one of the key benefits for these countries that will flow from TPP is access to US markets, particularly in terms of textiles and garments where US tariffs are still quite high.

“That agreement will be amazing for Vietnam, itʼs almost like it was written for Vietnam,” says Dan Harris. “A lot of people are excited about what TPP can mean for Vietnam, and theyʼre doing exploratory missions to Vietnam because of TPP.”

No Time Soon

But for all this, China still has huge advantages, and the countries looking to cut into Chinaʼs dominance of manufacturing are still bedeviled by a long list of problems of their own.

For one thing, China has deep manufacturing know-how, experience and the most sophisticated supply chain platforms on the planet, something that rival manufacturing companies simply canʼt compete or replicate. Its infrastructure and industrial clusters give it a huge edge, and China is where a lot of components will ultimately be sourced from anyway. It is perhaps unsurprising then that at the same time as opening its new factory in Vietnam, Intel opened an even larger facility in Dalian, with this factory dealing with the actual manufacturing of chips—the Vietnam factory merely handles assembly and testing.

“China is just so ready, I mean itʼs so easy,” says Harris. He points to the sheer wealth of choices that a company has in China when choosing a manufacturing partner, even in a single region, and the countryʼs ability to produce highly complex goods in such phenomenal quantities.

Moreover, China is a huge country with many places, principally inland, where labor costs still havenʼt reached the same heights as those in the coastal regions, for manufacturing to potentially move to. In Standard Charteredʼs survey of Hong Kong and Taiwan manufacturers in the Pearl River Delta, a shift to inland areas was greatly preferred to moving capacity out of China.

An HSBC Global Research report in September identified three such areas: Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei (nicknamed “Jing-Jin-Ji”); a “New Silk Road economic belt” with strong links to central Asia that includes nine provinces, five of which are in the northwest; and a Yangtze River economic belt upstream from the traditional manufacturing hub of the Yangtze River Delta.

In October, Airbus announced plans to open a completion center for its A330 planes in Tianjin, and Foxconn jointly opened a laptop production facility in Chongqing in 2012. However skepticism remains for many companies over the idea of diversification solely within China given the concerns that go beyond wage costs. Infrastructure cannot match that of the coastal regions, and a high-profile strike at Foxconnʼs Chongqing factory in October also raises questions of how viable these inland areas are as alternatives.

However the fixation on costs also overlooks the appeal China has because of its growing market. “I think what keeps companies in China is above all the future,” says Mats Harborn, Vice President of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China and Executive Director of the Scania China Strategic Office. “The clear shift is that companies are now in China for exploring the Chinese market—companies are not in China for having China as a production base for export… that is the way we perceive it.”

Beyond having to compete with Chinaʼs strengths, the countries that can potentially benefit from the China Plus One strategy come with their own flaws. Infrastructure tends to be less developed than China, and for Vietnam and others, a huge issue is skill shortages. “Despite impressive literacy and numeracy achievements among Vietnamese workers, many Vietnamese firms report a shortage of workers with adequate skills as a significant obstacle to their activity,” noted the World Bankʼs 2013 Vietnam Development Report.

Organizational structures of businesses also affect the prospects of China Plus One gaining traction. Devonshire-Ellis considers the management of many firms operating in China as being too China-centric and so oblivious to other opportunities in Asia. “I think thereʼs a knowledge gap of the financial incentives and tax incentives that are available,” he says, adding that many in senior management have a vested interest in staying in China. “Thereʼs a danger for global manufacturers that are in China and relying too much on their China-based executives [and] Chinese executives to dictate the future of the China operations.”

The practical limits of China Plus One strategies are also revealed by examples of companies that talk about it, but have so far not actually made the move. In February 2014, Foxconn signed a letter of intent to invest $1 billion in Indonesia, claiming that more detail would be forthcoming within three to four months, but as yet no actual investment has materialized. In September, Chatib Basri, the then finance minister of Indonesia, told Reuters that Foxconnʼs demands for free land and generous tax incentives were unrealistic.

That is not to say that China should be sanguine about the situation, even if China Plus One perhaps doesnʼt represent an immediate and significant threat to mainland manufacturers. The fact that talk of such strategies refuses to die down, and on the contrary has become more intense, illustrates the very real concerns of some companies about Chinaʼs business environment.

“How many of those [companies considering China Plus One] are actually pulling the trigger? Not that many, not a large percentage. But theyʼre getting ready,” says Harris.

The concerns are part of the overarching shifts in Chinaʼs economy as it moves from being the low-cost workshop of the world to being a country based on consumption and higher-value manufacturing.

In fact, if anywhere does look set to take the “factory of the world” mantle from China, it is perhaps a country that, although sometimes mentioned in the context of China Plus One, is nonetheless too large and full of potential to be merely a supplement to a neighboring nationʼs manufacturing might: India.

India today finds itself in the same demographic sweet spot that China was in years ago, and it currently benefits from a strong, business-friendly national government with a mandate for reform. Devonshire- Ellis points to Chinaʼs agreement in September to invest $20 billion over five years in Indian infrastructure as a sign that China is ready to “pass the baton”.

“If you have an increasingly wealthy Chinese society, that still means they need cheap goods, and if Chinese labor is becoming expensive and cannot provide that, then Chinaʼs consumers need to be able to obtain those cheap products from another market,” he says. “Frankly, itʼs only India that has the workforce size and the cost base that is able to provide the huge Chinese market with the low-cost products it requires.”