Brexit has changed China’s relationship with both the UK and the EU

On the morning of June 24th, 2016, China woke up to witness an unexpected drama unfolding half a world away. The previous day, millions of UK citizens had voted on whether the UK should remain in the European Union, and all opinion polls, betting and market expectations pointed firmly towards ‘Remain.’ But as the early results came in, as China was eating its breakfast, the startling prospect of Brexit became a reality.

With typical British understatement, Mark Pinner, Managing Director and Partner at Interel China, a public affairs and government relations consultancy, called the result “a bit of a shock.”

The reasons divined for the ‘leave’ vote were many, but one consistent theme was a desire of British voters for Britain to make its own decisions, and to chart its own course in the world. The effect, however, could be to redraw the economic map, requiring companies and governments to rethink long-held assumptions concerning market access and investment strategies.

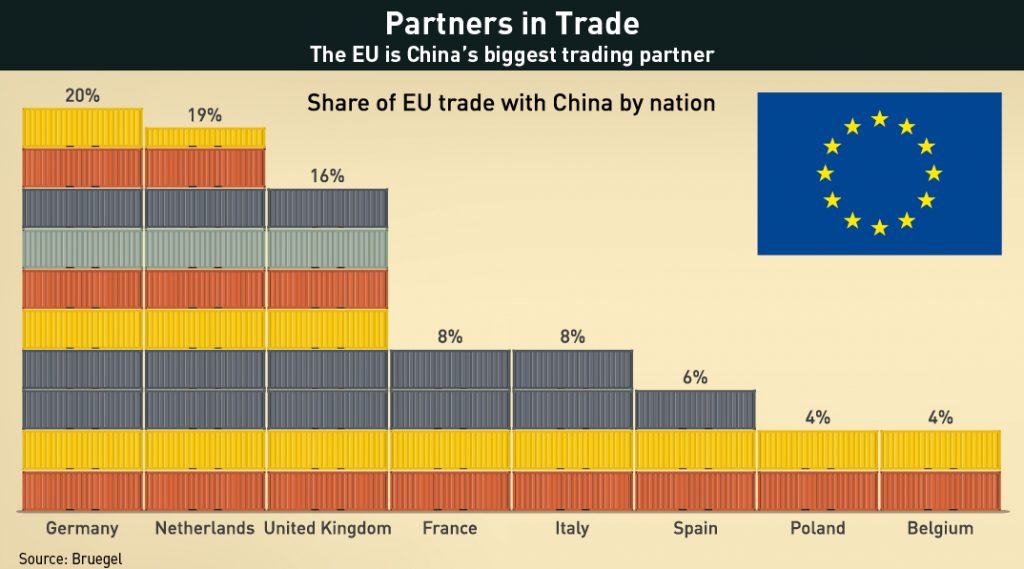

Furthermore, although the EU is for now China’s largest trading partner—accounting for nearly €190bn in imports in 2015 and €321bn in exports, or nearly 16% of China’s total exports—losing the UK will mean the EU will once again come second to the US.

China and the EU

How exactly Brexit would affect China’s relations with the EU prompts much disagreement.

Writing in September about China’s relationship with the UK, Jie Yu—China Foresight Project Manager at LSE IDEAS, the foreign policy think tank of the London School of Economics—highlighted how it complicates Chinese investors’ plans to enter the 500m-strong European market, noting that “Brexit has indeed diminished Beijing’s hopes of treating the UK as a strong advocate for China in the EU.”

But Song Gao, Managing Partner at PRC Macro Advisers in Beijing, an economic forecasting firm, disagrees, arguing that investment in the EU is small compared to exports.

“The Chinese… have other ways to penetrate the EU market, for example [through] Greece,” he says, noting Chinese support of the Greek government and projects like ports.

In a sense, they are both right. Chinese investment in the EU has so far been limited, but it is on the rise. China’s investment in 2013 was only €4.7 billion out of a total foreign direct investment into the EU of €621 billion, but in 2014 it rose to about €8 billion, or 6.5% of €119 billion total FDI, and has certainly grown further since.

Song, however, focuses on the more political dimension of the economic risk.

“China is apparently going to lose an ally within the EU Council,” says Song. “That could [threaten] China’s pursuit of free market status designation from the EU.” According to the terms of the agreement reached to allow China into the World Trade Organization in 2001, China was to be given “market economy status” at the end of 2016. However, the EU balked earlier this year, due in part to issues of alleged steel dumping related to China’s continued support of state-owned enterprises.

Other fair trade issues have further ratcheted up the tension. The €670 million Chinese acquisition of German chip manufacturing technology company Aixtron was held up in October. The breakdown in the deal was due at least in part to German security concerns, but broad issues of fairness and reciprocity likely also played a part. Chinese firms have been on an M&A spree in recent years, prompting other countries, Germany not least among them, to complain that foreign firms are restricted from acquiring similar companies in a huge range of Chinese industries.

It would appear, therefore, that there are more potential roadblocks to China’s EU investment strategy whether the UK remains a member or not.

Golden Relationship?

Also in play is the so-called ‘Golden Relationship’ between the UK and China, which has been assiduously cultivated in the past couple of years.

Part of this relationship is based on institutional cooperation and access to London’s financial services and currency markets, but the more important consideration for the UK is China’s growing investments in infrastructure. The Hinkley Point C nuclear power station is the best example. Despite doubts following the historic vote, the project made headway in the post-Brexit UK with final approval for the deal given by the UK government in September.

Song Gao considers this kind of infrastructure investment rather than access to the EU as being the key factor in China’s future relationship with the UK. The opportunity derives from the perceived need for “the UK to promote investment in infrastructure to offset the economic headwinds from leaving the EU.” That in turn will create more investment and financing opportunities for China.

“The Chinese would love to jump in and provide financing for infrastructure investment in the UK,” Song says.

Salvatore Babones, Associate Professor of Sociology at Sydney University, Australia, is less optimistic about China’s long-term interests, but instead sees opportunity for Britain.

“The UK may be willing to seize opportunities to fleece the Chinese government on big financial deals,” says Babones. “The English have had an eye for a good deal for half a millennium now, and if China wants to subsidize British infrastructure, the UK government will let them.”

But Brexit also throws London’s status as a financial capital into question, and that may very well put a hold on many deals.

“There will be more hesitation before major commitments in the financial area [until] the picture gets clear,” says He Jun, Career China Fund Manager based in Hong Kong.

However, the main problem with gauging the consequences of Brexit on the China-UK relationship is that the process is uncertain, and the outcome unknown. There is now a little more clarity with the promise to invoke ‘Article 50’ by the end of March 2017, implying a likely exit date by April 2019. But that also means nothing can be formally discussed until March of 2017, after which the negotiations promise to be highly complex.

“Britain can’t really undertake detailed trade negotiations with other countries until it leaves the single market,” says Pinner.

Nevertheless there is a fairly strong impression that China will want to strike a trade deal with the UK.

“It is very likely that UK and China will sign a free trade agreement after Brexit,” says Song. “[Brexit] will simply make Britain more flexible in terms of negotiating trade agreements with third-party countries outside of the EU.”

To that end, high-level discussions between the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer and one of China’s Vice-Premiers have been scheduled for November, according to an announcement in October by Liu Xiaoming, China’s Ambassador to the UK.

China and Brexit: The downsides

There are, however, some specific challenges that confront China in the short term. The most obvious is the effect on China’s currency of the Brexit vote, and now also the US election of Donald Trump.

“The new RMB overall currency policy now is targeting a basket of currencies,” says Song. “So [while] Brexit will have a huge downside pressure on the Pound … the Chinese currency has to follow.”

He adds that policy makers worry the market will see such depreciation not in the context of targeting a basket, but in the context of a broader weakening of the Chinese economy.

The bigger concern though is about the spill-over effect of Brexit on the entire European Union, the fear being exits of more countries, such as Italy, or even a collapse of the Eurozone. “The Chinese are extremely worried about this prospect,” Song says.

He Jun concurs, though is perhaps more sanguine.

“It is obviously hard to gauge exactly what Brexit means to the world ultimately,” says He. “So far the Chinese government is taking a relatively relaxed attitude on the issue and their chief concern is whether it will create another round of 2008-style global systematic risk.”

Babones takes a contrasting view, believing that the problem will be less about economics than politics.

“Post-Brexit Britain will inevitably move closer to the United States,” he says. “Chinese policy coups like the Hinkley Point nuclear contract and Britain’s decision to join the AIIB will be less likely in the future.”

China and Brexit: The upsides

There are some bright spots, however. The most obvious opportunity stems from the immediate decline—as much as 18% by the end of October—in the value of the Pound.

“[This] makes Britain very attractive to investors,” says Pinner. “Tourism from China is booming and investment in … real estate has jumped very significantly, too.”

Song goes further: “Chinese SOEs have been instructed to purchase technologies and more productive sectors from foreign countries, so the Chinese see this as a great opportunity for them to increase their ODI.”

In a more strategic sense, however, the biggest opportunities may not be economic.

“The Chinese government sees a less unified Western world more as an opportunity politically,” says He Jun, which “leaves the way open for China to gain concessions [and]… win support from at least some of the European countries on some issues.”

Babones agrees, further speculating about the opportunities thrown up by a weakened EU.

“The post-UK European Union is likely to be more amenable to—or vulnerable to, depending on your point of view—Chinese diplomatic initiatives as the overlap between the EU and NATO declines,” he says.

But the division also has the potential to overshoot, which is a big concern for China.

“[The EU may] become more conservative in terms of global trade.” says Song.

That touches on the wider current phenomenon of de-globalization, with which Brexit has been identified.

Walling Off

In the broadest sense, Brexit’s challenge is philosophical as it points to a fragmentation of the existing institutional order. In this way, it is linked to other trends around the world, including a rise in protectionism and a threatened reversal of the long post-war trend towards increasing trade and interdependence.

“The growing anti-globalisation sentiment in developed countries is very much noticed among Chinese academics and investors,” He Jun says. “Brexit should certainly be viewed as part of that development.”

Indeed, He Yafei, Vice-Minister of Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council, made exactly this point a week after the vote, stating that “from a strategic and global perspective, Brexit may be defined as the first wave of anti-globalization and rising populism that washes over the world.”

In the wake of United States’ election of Donald Trump as president, he may have been correct.

At the most recent BRICS meeting in India in Mid-October, President Xi Jinping himself warned that a “rising tide of protectionism and anti-globalization was endangering the world economy’s still fragile recovery” blaming “deep-seated imbalances that triggered the financial crisis.”

But Salvatore Babones, whose academic work focuses on de-globalization, says that this is not new.

“The falling trade between China and the rest of the world is part of a long-term super-cycle,” he says. “The era of increasing globalization came to an end in 2008.”

Babones also sees de-globalizing forces at work in China’s efforts to carve out a stronger sphere of influence in the South China Sea. And while this may not represent an absolute retreat from trade, it is shifting toward a system that is more regional, rather than truly global.

Re-globalization and Brexit?

But what Babones sees as ‘de-globalization,’ others see as ‘re-globalization’—a response to deglobalization that envisages creating new patterns of trade, perhaps regional or sectoral, as a way of forestalling an expected downturn in global trade. Song sees China’s efforts in the last few years, in particular with the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative and its associated institutions, as a specific response to China’s long-held expectations of more difficult trading conditions.

“The political dynamic is definitely shifting against globalization and this trend is not going to reverse anytime soon,” says Song. Expanding on OBOR’s reach into the central Asia, he adds that the Chinese initiative “[involves] the corridor that has been very much excluded from the previous wave of globalization.”

“[These areas] lack the infrastructure [and] financing to facilitate trade,” he adds.

And this brings the whole question back to a wider context in which Brexit could be a remarkable opening for China. It is within the potential for “re-globalization,” a re-thinking of the globalization process, that China may see the opportunity to deepen its relationship with the UK—and with a more fragmented EU—to complement its long-standing efforts to promote regional trade initiatives from a more global perspective.

While the UK may be a relatively small economy, it is very global in outlook, with strong connections and institutional presence all around the world. In that sense, the UK leaving the EU just as its relationship with China has matured is seen, in Song’s words, as a “great opportunity for China and Great Britain.”

Clearly the huge uncertainties that still hang over Brexit make prediction difficult, but inevitably China will need to rethink its relationship with the EU. Having lost a sympathetic voice on the inside, there is a danger that the EU will now be more suspicious of China’s intentions, as recent decisions on mergers clearly show. Nevertheless, a more flexible UK will provide some very obvious opportunities for Chinese investment, just as the EU will maintain an overwhelming interest in continuing to improve trade.

The key danger for China is if Brexit goes badly wrong and somehow helps to trigger a global downturn, but as the chances of that slowly diminish, China may find itself moving beyond the shock of the event and looking toward what is next.

“We should be confident in a promising future for China-UK relations,” said Vice Premier Liu in October, when announced China-UK talks. “What is more, we should seize the opportunities when they come along.”