Over the past decade, publishing has undergone a revolution, perhaps the most profound since Gutenberg. In this series, we’ll look at how digitalization has changed book consumption, book production, book marketing—and how it may ultimately even change the nature of books.

In Part 1 and Part 2 we talked about the Rise of E-books and Writers and Self-Publishing. The third Part is E-Book Production, Marketing and Sales, in which we take a closer look at how digitalization has changed the way books are edited, designed, and marketed. You can also find E-Publishing with Chinese Characteristics in Part 4 of this series.

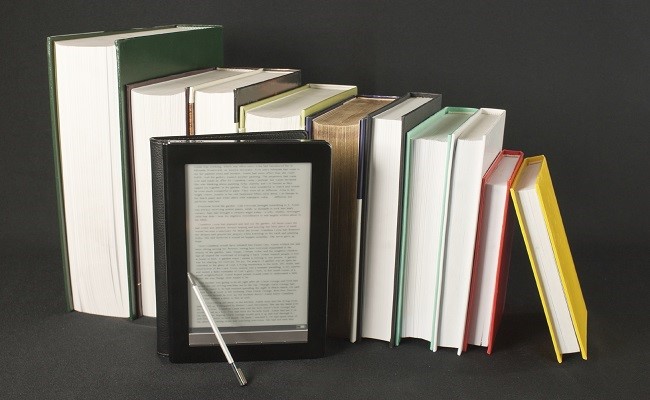

Part 1: The Rise of E-reading

On November 18, 2007, the book business looked more or less the way it had for decades: an industry dominated by a handful of conglomerates that produced a set of products that hadn’t changed much since the 1940s and distributed those products through a familiar set of sales channels.

The next day, Amazon introduced its Kindle e-reader and everything changed. Not all at once, of course—the Seattle company’s first e-reader retailed for $399, and after selling out in 5.5 hours, remained out of stock until April 2008—but over the next few years, the numbers grew at the same pace with which many digital innovations, from the internet to social media, have taken off: by 2014, half of all Americans owned either an e-reader or a computer tablet, and 28% had read an e-book in the prior 12 months, according to a survey by the Pew Research Center.

All over the world, a similar shift has been underway—slower in markets where bookstores and book sales are regulated, such as France and Germany; faster in more open markets, such as China, where more than 2 million digital book titles are now available and nearly half (44%) of all books sold are sold online, according to a report by German Book Office Beijing.

Yet a surprising thing happened on the way to the digital bookstore: even in the US, a largely unregulated book market, most book buyers still end up with books they can set on their bedside tables. In 2016, in the US trade market, publishers sold nearly 810 million print books, compared to nearly 486 million e-books and 42 million audio books, according to a tally prepared by AuthorEarnings.com.

In contrast to the way MP3s swept away physical CDs and the DVD displaced VHS, print seems to be sticking around. Even the younger “digital natives” who analysts thought would be big e-readers have reportedly not given up on paper.

“What distinguishes delivery of books from digital delivery of movies and music is that the consumption experience changes,” says Mike Shatzkin, founder and CEO of the Idea Logical Company, a New York publishing consultancy. With movies and music, watching and listening to a digital file is the same as watching or listening to an analog product, he says, but reading a digital book is a different experience.

“A lot of people prefer print—they just do,” says Shatzkin. “Even now that we’ve got to the point where everybody has got a device that they could read a book on…people are perfectly happy to buy a printed book and carry a printed book and read a printed book.”

So was publishing’s digital revolution just a successful format change, like the invention of the paperback in the 1940s? Not entirely. Digitalization has also driven a much more profound story about how books are made and sold. From production to distribution, virtually every aspect of the publishing business has changed over the past decade.

To begin with, thanks to e-books and print-on-demand technology, the actual process of printing a book has changed. David Kudler, a small publisher in the San Francisco Bay Area, says that e-books and print-on-demand technology have been transformative. “When I first got into publishing, printing was real simple. You got the book ready about six months before you wanted it to go to press, and you sent it off to China—that’s where the good presses were and that’s where the people who knew how to really put together the book were. And whether you were in Europe or in North America you waited the six months that it took for that book to show up in the stores again.”

The growth of e-books and publishing on demand also helped drive changes in how books are sold. In the US, physical bookstores now represent roughly a quarter of all book sales. Since 2007, US brick-and-mortar bookstore sales have fallen from $17 billion to $11.17 billion in 2015, according to US Census figures. All told, 69% of US books are sold online, according to AuthorEarnings.com.

The new technology also made it possible to publish without holding much inventory. For large publishers too, it meant that their backlist books never had to go out of print or at least not as quickly. “All of a sudden if you had a book that sold 100 copies a year or a thousand but it sold steadily, you could keep it in print. You have it printed on demand. When a bookstore wants it they order it. You print it, you send it. It’s a lower profit margin but it means that you have more books that are out there, which helps everybody,” says Kudler, who owns Still Point Digital Press. Small publishers too, were suddenly able to publish without much risk.

The main online web sellers looked at the same technology, Kudler says, and saw a different opportunity. “Apple, Barnes & Noble here in the United States and obviously Amazon—all of them took these same technologies and said, well, look at that: We can cut out these huge publishers and these big distributors and we can just go straight to the author or the small publisher,” he says. Suddenly, they could give them the same access to the reader as the multinational conglomerate. Kudler’s publishing house has been a beneficiary: “I am by no means a multinational conglomerate, I have a small publishing company, and I have books available on every continent.”

Other trends also helped smaller publishers. Hard times in the traditional publishing industry led to leaner staffs, making it easier for small publishers and authors to hire experienced editors, designers, and marketers on a freelance basis. Organizations such as BookBaby and Amazon’s CreateSpace sprang up to lead people through the entire publication process, along with smaller, more specialized agencies such as Reedsy and NY Book Editors.

For the small publisher, it’s all added up to a golden opportunity to produce books with relatively little financial risk. “All the things that require an organization can be got for a percentage of sales,” says Shatzkin.

Not surprisingly, as the barriers to entry have fallen, the number of books published has grown. Instead of 150,000 books coming out in a year, roughly 1 million now flood the US market, publishing experts say.

This boom in self-publishing has led to some unexpected hits, such as The Martian, Andy Weir’s nontraditional science fiction story about a shipwrecked astronaut, and E. L. James’ sadomasochistic erotic romance Fifty Shades of Grey, two books that Kudler believes would probably not have been brought out by traditional publishers, although they both found massive audiences online.

Publishing in this new era made it possible for the writers to bypass not only the agents and editors who act as gatekeepers in the traditional industry, but social pressure as well. At least in the case of the racy Fifty Shades, Kudler argues that one reason for its unexpected success was another feature of the e-book: anonymity. Readers like being able to read whatever they want in public without fear of a disapproving glance. “When I’m reading my pulp science fiction book, the cover has got the monster ripping the scantily clad woman away from her spaceship or whatever—it’s a stupid cover and the books are silly—but nobody knows that’s the book I’m reading. Because all they see is this,” he says, waving his charcoal-colored Kindle.

For publishers, this has created a double-edged sword, Kudler says. “E-books and the democratization of access from the publisher’s end has allowed for the consumer to get a much, much broader opportunity to read what they want to read as opposed to what the publishers want them to read. And so I think that’s a wonderful thing. The other side of it is that as a publisher it’s a constant challenge to figure out: well, okay, I’ve got this wonderful book…how do I find readers that are going to want to read it?”

One way independent publishers have tried is by lowering the price. Low costs and high margins mean that small publishers, who may be taking home as much as 70-80% of every dollar, have tried to lure more readers by charging less for their books—sometimes even nothing, in the hopes of encouraging positive reviews on Amazon and by word of mouth.

Depending on the genre, the strategy seems to have worked more or less well: the average self-published romance novel e-book may have sold on Amazon for $2.92 compared to the $6.88 paid for a romance published by a Big Five publisher, but 55% of the market is now owned by self-published writers. In fact, only 34% of the e-book romance novel market now belongs to traditional publishers, according to AuthorEarnings.com.

Partly because of this price differential, self-publication, far from being considered the shameful vanity project it was for most of the 20th century, now offers a competitive advantage. “For every reader discovering a new Big Five author, there are literally dozens of readers finding brand new indie authors and Amazon-imprint authors they enjoy,” write the AuthorEarnings.com analysts. “…High e-book prices make newer authors invisible to the vast majority of avid readers, who don’t care how a book is published.”

AuthorEarnings.com estimate that there are now more than 1,080 self-published e-book writers, most of whom made their debuts within the last five years, who earn more than $50,000 a year from their Amazon sales.

As Shatzkin noted in a blog post, these changes have created an enormous business challenge for publishers. “The ability to put a book into the marketplace in a way that can reach more than half its audience with no inventory investment, making it possible to sell books and rights globally and only later, if it is warranted, put a bigger bet down on the book—combined with the increasing number of entities that have knowledge that could inform content and direct contact with a real market—is going to be transformative,” predicts Shatzkin. “Everybody in the chain but the author and the reader are fighting for their lives.”