October 2020 proved to be a watershed moment for state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China. China’s investor community reeled with shock when it discovered that the Shenyang-based Huachen Automotive Group, one of China’s largest state-owned enterprises (SOEs), had more than $20 billion in debt with cash reserves that could only cover a quarter of it. Things moved fast and by November, the massive group had entered bankruptcy proceedings.

What was extraordinary about the development was not so much the size of its debt, but the fact that such a massive piece of China’s state-owned ecosystem was apparently being allowed to go bankrupt. For perspective, Huachen has controlling stakes in four public-listed companies and for the past 20 years, it has been the joint manufacturer of BMW vehicles in China.

Such a bankruptcy would have been unthinkable even a few years ago, but suddenly all bets were off and the steadfastness of SOEs came into question. Huachen, which employs 47,000 people according to its website, is not alone among SOEs in its debt-heavy predicament—two other major SOEs which have recently defaulted on debt repayments are Yongcheng Coal and Electricity on a payment of $151.9 million and chipmaker Tsinghua Unigroup on $198 million.

Despite often being poorly managed and lacking transparency, SOEs have over the years received high credit ratings from international as well as domestic lenders because of an implicit assumption: that the state will not allow them to fail. In their pecking order of goals, SOEs place social stability and employment ahead of profitability—unlike private enterprises whose priorities are clearly different.

“Local governments in China have long been so reluctant to let their SOEs go under because the firms are used to provide employment and social welfare, which is closely linked to social stability,” says Tianlei Huang, Research Fellow at US think tank Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE).

The lesson from the Huachen episode seems to be that this is no longer necessarily a valid assumption across the board.

Ever since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, SOEs have been the anchor and foundation of the Chinese economy. And while the economy today has broadened to include huge numbers of private enterprises, SOEs still play a crucial role in facilitating China’s state-mandated economic agenda.

SOEs make up 70% of Chinese companies on the Fortune Global 500 list and more than 50% of China’s 500 biggest companies by revenue. SOEs are the dominant or only players in a wide range of sectors including energy, telecoms, aerospace, finance, transport and construction. As outlined in Beijing’s 14th Five-Year Plan in March, the government views the continued strengthening of the SOEs as key to improving China’s economic system and reaching its strategic development goals.

While there is no doubt that China will continue to prop up almost all of its national champions, the rash of recent default cases have inserted a seed of doubt into financial market considerations with regard to the prospects of SOEs, particularly smaller companies. Tens of thousands of SOEs report to local governments which over the decades tended to indiscriminately bail out financially stressed SOEs to avoid negative social ramifications. But today, Beijing is apparently encouraging officials to allow some unviable SOEs to fail, sometimes spectacularly.

Shattered faith?

Huachen announced in October 2020 that it would not be able to repay a privately-placed bond worth RMB 1 billion ($150 million), just six months after the group had told bond holders that it had adequate financial backing to service the debt. The following month, bankruptcy proceedings commenced, sending ripples through the financial markets. And before investors could wrap their heads around Huachen’s situation, Yongmei Group, another triple A-rated SOE, started defaulting on a series of bonds worth more than RMB 3 billion ($460 million). The default by the Henan-based coal producer, with total bonds outstanding worth RMB 47 billion, puzzled the market too, for Yongmei is one of the largest SOEs in the province and local authorities have every incentive to maintain its stability.

Senior officials in Henan told domestic media that the government was trying to resolve the issue “using market-oriented methods,” but could no longer direct funds to its SOEs “blindly without principles”.

“The provincial government in Henan was reluctant to bail out Yongmei because the government itself was struggling with its own surging fiscal deficits,” says Huang.

The low profitability of many provincial SOEs such as Huachen and Yongmei means that local governments have increasingly had to rely on Beijing’s support to bail out such companies, according to credit rating agency Lianhe Ratings. “In most of the SOE default cases that happened last year, local governments were less willing to bail out these distressed state firms, which was rare in the past. It seems like the implicit state guarantee is no longer a golden rule,” Huang adds.

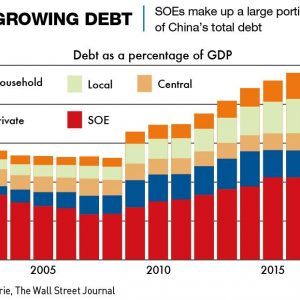

In 2020, SOE defaults blew up to RMB 98 billion ($15 billion). This was five times more than in 2019 and accounted for almost half of all bond defaults in the entire market. “It’s harder and harder for local governments to garner enough financial resources to pull off bailouts nowadays,” says a senior debt capital market (DCM) banker whose clients include many local SOEs. “They also lack influence on big banks because such large loans are now subject to approval by their head offices in Beijing.”

Before 2015, defaults of any sort were almost unheard of in China’s capital market, especially for SOEs. Investors would happily snap up SOE bonds without closely studying the fundamentals of the issuers, convinced that local governments would always step up to support them. But in recent years, China’s total debt has soared to 273% of the nation’s GDP, and the central government is concerned about both reducing the debt mountain and forcing SOEs to operate more efficiently.

There has been a debate at the top levels of China’s leadership ever since market reforms were first instituted in the late 1970s about the correct balance between state-owned and privately-owned companies in the Chinese economy. In recent years, statements from the center have encouraged assumptions on the ground that the leadership favors an expansion of the role of SOEs.

Some economists take the view that allowing unviable SOEs to fail could make room for emerging private businesses that would be more efficient, which would help boost the vitality of the Chinese economy. “It is a positive thing to always have new kids on the block,” says Xiang Bing, Founding Dean and Professor of China Business and Globalization at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. “That means the rise and fall of companies, whether they’re private or state-owned enterprises, is a healthy process.”

Following the Yongmei default, Chinese Vice Premier Liu He, who chairs the central government’s Financial Stability and Development Committee, publicly vowed “zero tolerance” for fraudulent debt-raising activities. Investment banks and rating agencies associated with the defaults were later slapped with hefty fines. By April, Beijing rolled out a tighter scheme to monitor local SOEs’ debt problems, imposing limits on various financial indicators for the firms. But while so-called faith in the SOEs may have been somewhat shaken, market analysts are generally of the view that such failures will always be carefully handled and that a run of large-scale defaults is unlikely.

Bittersweet memories

For long-time China watchers, this is a moment of déjà vu. “It’s a pale reflection of the changes that happened in the 1990s, when Zhu Rongji was determined to clean up the banks for global listings and reduce the influence of unprofitable state firms,” says Andrew Collier, Managing Director of Orient Capital Research, and author of Shadow Banking and the Rise of Capitalism in China.

Collier is referring to the vigorous SOE reforms spearheaded by then Chinese Vice Premier Zhu Rongji, who oversaw the closure of large numbers of SOEs in the 1990s. As many as 40% of SOEs at that time were losing money, putting huge pressure on the country’s fiscal and monetary systems. The result of Zhu’s reforms was millions of workers being laid off, but the burgeoning private economy in that era allowed them to find other work.

In 1995, the government declared that the reform of the SOE structure was at “the center of the restructuring of China’s economic system”, and the SOE management model was officially deemed “unfit to development requirements of the socialist market economy”.

In the years since, the surviving SOEs generally have become more efficient and have taken on many of the characteristics of major business groups anywhere in the world. But while the SOEs in some ways look like capitalist entities, they still publicly acknowledge that their first responsibility is not to be profitable on behalf of shareholders, but to meet state policy requirements. The SOEs provide employment and social services for millions of people.

Today there are an estimated 460,000 SOEs with total assets of RMB 234 trillion and a total of 50 million employees. They are supervised by the State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), which was set up in 2003 after China’s entry into the World Trade Organization.

A fine balance

Studies have shown that the SOEs have a significantly lower rate of return on investment and business efficiency than private enterprises.

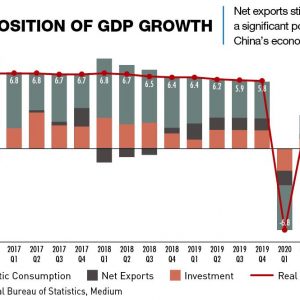

“Long-term profit maximization is indeed important for SOEs, but the objective is first and foremost to use SOEs to further national strategies, be it the Belt and Road Initiative, technological self-sufficiency or industrial policies like Made in China 2025,” says PIIE’s Huang. “SOEs are also used as a shock absorber during crises,” such as the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Long-term profit maximization is indeed important for SOEs, but the objective is first and foremost to use SOEs to further national strategies, be it the Belt and Road Initiative, technological self-sufficiency or industrial policies like Made in China 2025,” says PIIE’s Huang. “SOEs are also used as a shock absorber during crises,” such as the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The social purpose or social function of SOEs may be used to justify their underperformance,” adds CKGSB’s Xiang. “Ten to 20 years ago, a [private] company that offered many job opportunities would very likely be welcomed by the mayor of a city. But the social function of enterprises is going to become more and more prominent in this new era. In this regard, SOEs may be looked upon more favorably today to shoulder more social burdens, as the government can impose policies on SOEs more easily than on private companies.”

Solving the SOE dilemma, making them more commercially efficient while allowing them to retain their crucial policy role, is one of the biggest problems that China’s leadership faces. One solution that has been floated is mixed-ownership, where private companies are introduced as strategic shareholders of SOEs to boost competitiveness.

Beijing is firm on its policy of encouraging the most important SOEs to be “bigger, better and stronger”. But on the other hand, it is grappling with how to “release the small”—essentially allowing the weakest of the SOEs to die without causing social or financial market disruption.

While gradually shrinking the role of SOEs in “competitive sectors” has been discussed many times over the years, implementation is another story. “There has been considerable pushback and friction around the designation of firms,” Huang adds. “The central SASAC has been working on the categorization policy for more than half a decade, but it has never released publicly what firms fall into which categories.”

The approach generally taken in recent years has been for the center to order the merger of failing SOEs with stronger ones to avoid public defaults. An example of this was the merger in 2016 of the weak Wuhan Steel with Baoshan Iron and Steel to become the Baowu Steel Group, now the world’s second-largest steel maker, just behind ArcelorMittal.

“On the surface, merged SOEs may present better financial statements right away. But does that really boost the efficiency and competitiveness of the business?” the DCM banker asks.

Beijing is now developing a legal framework to facilitate SOE bankruptcies, and in 2019, established six specialized bankruptcy courts and issued new interpretations of the bankruptcy law, as well as improvement policies to fix the loopholes.

“The greatest challenge was getting a court’s acceptance of the bankruptcy case, because Chinese courts are reluctant to accept and administer such cases,” says Xiao Ma, a visiting Harvard Law School scholar and Doctor of Juridical Science candidate who specializes in bankruptcy laws. “As bankruptcies become less uncommon, the public has to gradually adapt and develop a healthy expectation for bankruptcy processes.”

Whether it is bringing in new shareholders, creating synergies through M&A, or facilitating bankruptcies using legal methods, China is treading extremely carefully to maintain a fine balance in one of most complicated SOE reform processes in the world. As for SOE defaults and failures, there may very well be more of them in future. But as the country doubles down on its current development model stressing the role of SOEs, one can also expect the continued strengthening of the overall SOE system. “They want to have it both ways, it’s a classic Beijing answer,” Collier says.