China has taken the lead in the global shipbuilding industry, followed closely by South Korea and Japan. Will they be able to hold on to their top spot?

The H1416, the largest container vessel in the world, was launched from Shanghai’s Wai Gao Qiao shipyard last year and the world’s largest Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) carrier is currently under construction in the northeast China port of Dalian. In fact, more than four out of every 10 of the large ships sailing around the globe today were made in China.

It appears to be full steam ahead as China aims to take an even greater lead in the world shipbuilding industry. “China is now the world’s biggest shipbuilding nation,” said Kevin Oates, managing director of Marine Money, at the 2019 China Ship Finance and Offshore Summit in Shanghai. But there are also some difficult crosscurrents that China has to overcome if it is to consolidate its hold on the top position in global shipbuilding, including technology where it is in some cases behind, and costs where its main shipbuilders suffer from over-staffing.

In the lead

In 2018, the world merchant fleet totaled 1 billion deadweight tons (DWT)—a measure showing how much weight ships can carry, comprising over 50,000 vessels with a value of $851 billion, according to the Norwegian Shipowners’ Association. The vast majority of these ships are general cargo carriers, followed by tankers, container ships, passenger ships, bulk carriers and LNG tankers, mostly built in one of three places—China, Japan or Korea. Europe, the only other serious player, contributes a small fraction of the total number of ships internationally.

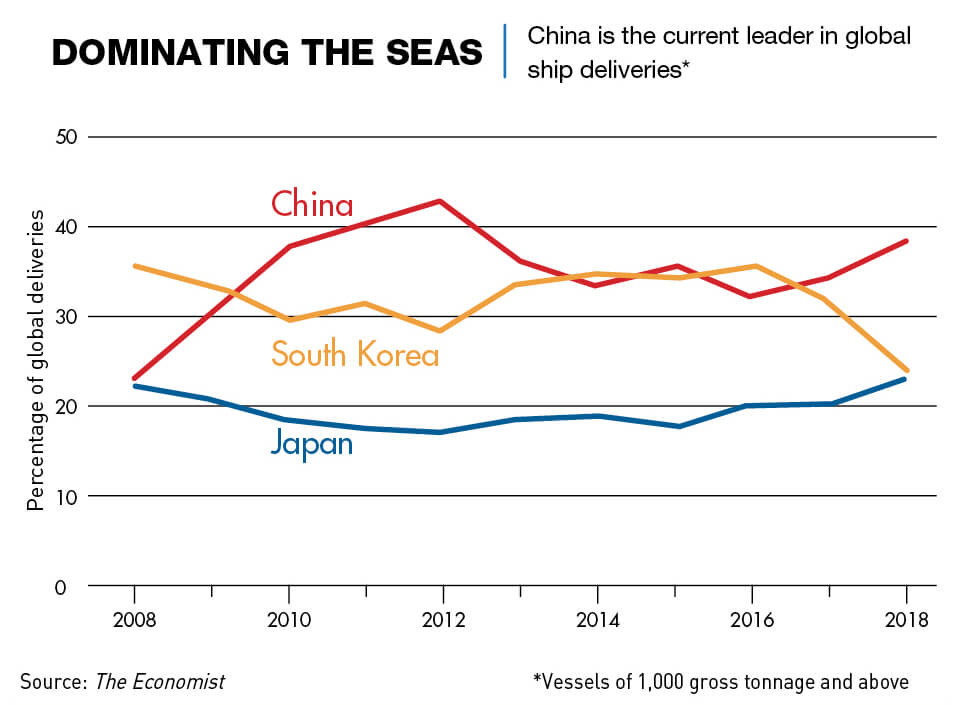

China became the leading shipbuilding country in 2017 when it launched ships totaling 23.6 million gross tons, followed by South Korea with 22.6 million and Japan in third place with 13 million. China, Japan and South Korea together produced over 90% of all ships launched in 2017.

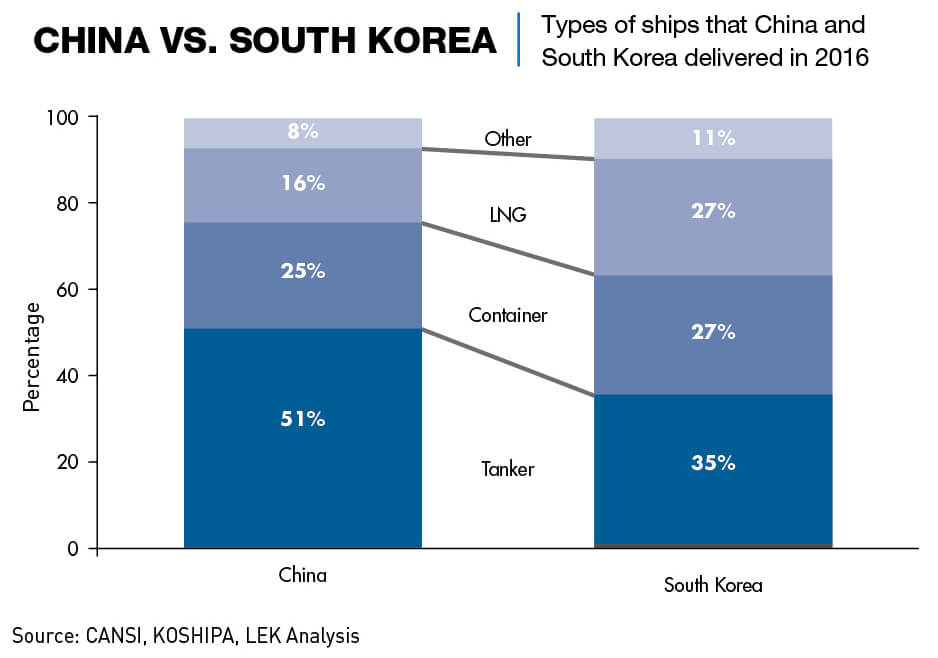

In terms of the types produced, China dominates in the production of bulk carriers—China’s market share in 2018 was 62% for bulk carriers—while South Korea dominated in oil tankers, with 50% of launched tonnage in that category. The market for containers ships is pretty evenly split between the three countries. And the market is expected to continue to grow.

An age-old industry

China has been a big player in shipbuilding for more than 2,000 years. Chinese ships capable of carrying about 1,000 tons started appearing around 1,000 BCE, and in the early 15th century, oceangoing junks were trading with Southeast Asia, India and even East Africa. But the voyages were halted after the death of the Ming Emperor Yong Le in 1424, leaving a vacuum in global shipping which European sailors filled in the centuries that followed.

The Portuguese and Spanish, followed by the British, the Dutch and the French, sailed the world and created huge empires in an era of colonialism that only ended after World War II. For a long time, the Americans and British dominated shipbuilding, but Japan leapt to prominence in the 1960s, then Korea in the 1980s and China in the 1990s. The key drivers of shipbuilding growth in each case were ample steel production, availability of skilled labor, technological developments and large-scale government support.

“China has become a leading shipbuilder due to its policy and support mechanisms for the shipbuilding industry,” says Nitin Agarwala of the National Maritime Foundation, a think-tank based in New Delhi. “It all began with the US, changed hands to the Europeans, then the Japanese followed by the South Koreans and now the Chinese.”

The deep-sea drilling boom has also contributed to East Asian dominance, with China and South Korea providing 80-90% of hull parts for semi-submersible vessels. But the export-oriented nature of the three economies was also a crucial factor.

“Shipbuilding has been a key part of the economy in East Asian countries,” says Sara Hsu, associate Professor of Economics at State University of New York. “Because these economies either were or are large exporters of manufactured goods to the rest of the world.”

China Inc.

While China, as a country, leads the shipbuilding market, the two largest shipbuilding companies in the world in 2019 were both South Korean; Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering and Hyundai Heavy Industries. The China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation, state-owned, was the third largest.

After nearly 10 years of planning, Beijing in late 2019 announced plans to merge the country’s two largest shipbuilders—Shanghai-based China State Shipbuilding Corp. (CSSC) and the China Shipbuilding Industry Co. (CSIC)—in order to cement the country’s position in the industry’s international rankings. The merger creates a shipbuilding titan with combined annual revenues of up to RMB 1 trillion ($141.5 billion) and capable of building vessels ranging from container ships and oil tankers to warships.

The tactic of consolidating state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to achieve greater efficiency and sometimes global advantages has been seen in a number of sectors. China began restructuring its SOEs in the 1980s, to introduce greater efficiency into companies that operate at home with the protection of monopoly control of the market. In the 1990s, there was a trend toward breaking up large SOEs into smaller units that to some extent competed with each other, but in the past decade, there has been a shift back toward mega-mergers to control debt, improve management, reduce unneeded production capacity and make the companies more efficient to fight for global market share in their sectors.

Mergers, such as the one being rolled out in the Chinese ship-building industry, effectively flattens competition as it is impossible for ordinary companies to compete with what is essentially the government. This has been a point of contention between China and Europe and the US for many years, because it gives Chinese SOEs a big advantage over private companies.

“Globally speaking, mergers are how the government creates champions to succeed in [the] global market,” says Xinling Wang, research manager at advisory firm China Policy in Beijing. “Unlike Western officials, Chinese officials believe big companies equal success. They would pay little attention to issues such as having a monopoly.”

It is important to note, however, that China is not alone in consolidating its shipbuilding industry—South Korea has also been planning a merger of Daewoo and Hyundai. Japan lodged a WTO dispute against South Korea in 2019, claiming that large government subsidies and significant state involvement in the industry were contrary to market regulations.

Weathering storms

The shipbuilding merger in China is clearly aimed at ensuring the country can maintain its lead in the global industry and provide a buffer in the face of growing economic headwinds. China’s economy has been slowing over the past few years and is expected to slow further, and the industry faces many challenges including shrinking profit margins.

“The policy right now is to strengthen state industries by consolidating them into two or three large companies,” says Penelope Prime, founding director at China Research Center, Georgia State University. “In China, the leadership wants to increase control over key industries and resources.”

Product specialization and shifts in demand for different types of ships also poses a major problem. “A shipyard, if constructing bulkers, manufactured only bulkers and had no capacity and knowledge to undertake construction of any other type of ship,” says Agarwala. After the global recession of 2008, “demand for many types of vessels dried up, forcing shipyards to relearn shipbuilding by changing their product of manufacture.”

To protect the industry and save the jobs of tens of thousands of shipbuilding workers, “the central leadership undertook a study to merge and consolidate shipyards that could be merged. In fact, China as a nation has gained immensely by this consolidation wherein shippers and shipping companies have grown in China with shipbuilding and trade originating from China.”

But keeping shipbuilding costs down and maintaining the jobs and salary levels of workers are often incompatible goals, and competition had forced some smaller, less efficient shipyards to the point of bankruptcy. The answer has often been for the central authorities to insist on mergers rather allowing companies to go under.

“[The] government is most concerned with the overcapacity in this industry,” says Wang. “Mergers and acquisitions have been pushed by officials as a way for profitable companies to take on their loss-making ones, to prevent massive lay-offs and social unrest.”

The growth in global orders over the long term has generally fallen. “As global trade expansion slowed … orders shrank significantly after the global financial crisis in 2008,” says Wang. “This general trend has not changed.” The slowdown led to the consolidation of production around the world into the hands of an ever-smaller number of ever-larger companies.

“The concentration of output peaked in 2008 and [was] at a similar level in 2018, with 20% of shipyards accounting for 80% of output and, remarkably, 6% of yards producing half the ships in [gross ton] terms,” says Stuart Nicoll of Maritime Strategies International, an business advisory firm based in London. There is a “slowdown in new building demand, in part due to uncertainty among shipowners about investing in ships with a 20+ year life expectancy at a time of such rapid change.”

Competition in the shipbuilding industry is fierce, with China and South Korea battling it out for the largest portion of market share. South Korea was for many years the top player before China took over in 2017.

“Demand for ships is driven by ship replacement and requirements for new ships,” says Laurent Daniel, shipbuilding expert at the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). “Global GDP (gross domestic product) and international trade, driving seaborne trade, are key factors driving the shipping industry.”

China is the unquestioned world leader in many industries, but is not so clearly dominant in shipbuilding due to overcapacity and overstaffing of its companies, technology shortfall and relatively inefficient yard management, all of which have given the shipbuilders in Japan and South Korea a chance to remain competitive. South Korea in particular has developed efficient production processes that keep costs down and leads in the increasingly complex technology integrated into the latest versions of massive ships. The early consolidation of its shipyards into two giants‡Daewoo and Hyundai‡allowed South Korea to capitalize on its technology advantage ahead of the competition in a wider range of ships.

Shipbuilding is “slow to absorb and move to new technology,” says Agarwala. “Newer technologies such as solar power and 3D printing, light weight structural materials … have still not found their way into the shipbuilding and shipping industry due to a lack of human expertise and the inhibition of ship-owners to introduce these technologies due to inherent added costs.”

“The challenge for China is to increase production and match the technologies successfully applied by Korea,” adds Nicoll. Digitalization is increasing, “manifested by increased remote monitoring of ship machinery to improve reliability. New propulsion fuels, energy efficiency measures, autonomous ships, increasing regulation and decarbonization. These are the watchwords for the industry.”

Broad horizons?

Increasing regulatory oversight of ship construction by the International Maritime Organization is having an impact on the industry. “The focus is now heavily on the evolution of more efficient ship designs and, more importantly, the search for low/zero carbon fuels. This issue will dominate the agenda over the next decade or so.” This is an area in which China is at a disadvantage. “China’s environmental protection has been weak,” says Wang. “This isn’t a clean industry, though it provides a lot of jobs.”

Companies that adapt effectively to these requirements will be in a strong market position, says Nicoll. “Such factors could be significant in terms of effective market power and the impact on price determination. There are opportunities ahead for those companies that can weather the current storm.”

And that means China’s position as the top player in the shipbuilding industry is not yet secure. Shipbuilding is ultimately dependent on global economic growth, the prospects of which are currently unclear. Pressure to go greener and introduce more advanced technology puts China at a disadvantage, while the large workforces at China’s main shipyards, all state-owned, hinder strategic moves into automation and niche technology sectors.

“China needs to embrace these trends to remain successful in the years ahead,” says Nicoll.