Jobs, Jobs and ... Less Jobs?

Long-held prejudices against blue-collar jobs are hampering the filling of vacant positions

Mimi Wang looks exactly as you’d imagine someone would after a two-hour class baking bread. Covered in flour, she says, “I was interested in doing a class and the government will reimburse me once I’m finished, so I thought, why not? But I don’t have any intention of going into baking as a career.”

The 27-year-old, who has a day job in PR at one of China’s larger internet firms, is one of many young Chinese taking advantage of government-sponsored vocational courses for fun, rather than for career development. In 2020, the Chinese government introduced a plan to create 35 million vocational skill training opportunities, ranging from baking to childcare, through to e-commerce and programming. But the fact that these courses aren’t always being used for their intended purposes is reflective of the currently paradoxical nature of China’s labor market.

On one side there is a labor shortage in blue-collar industries, while at the same time, there is a surfeit of unemployed university graduates. The issue is exacerbated by a widespread perception that blue-collar jobs are the inferior choice for any graduate, even though many university leavers have not acquired the requisite skills for the white-collar jobs to which they think they are entitled.

“There is something of a paradox in the labor market, with so many graduates coming out of higher education but being much more selective about the jobs they take up. As a result, there are huge numbers of vacancies in the factory sector,” says Lu Feng, director of the China Macroeconomic Research Center at Peking University. “It’s a very strange phenomenon.”

The rat race

Around 70% of Chinese businesses are currently contending with some kind of labor shortage, and the Ministry of Education estimates that there will be a dearth of 30 million workers by 2025. The issue is particularly acute for those in the country’s crucial industrial sector, as it contains 36 of the top 100 occupations with the most severe staffing problems. Countrywide, 55% of businesses report being unable to find enough blue-collar employees.

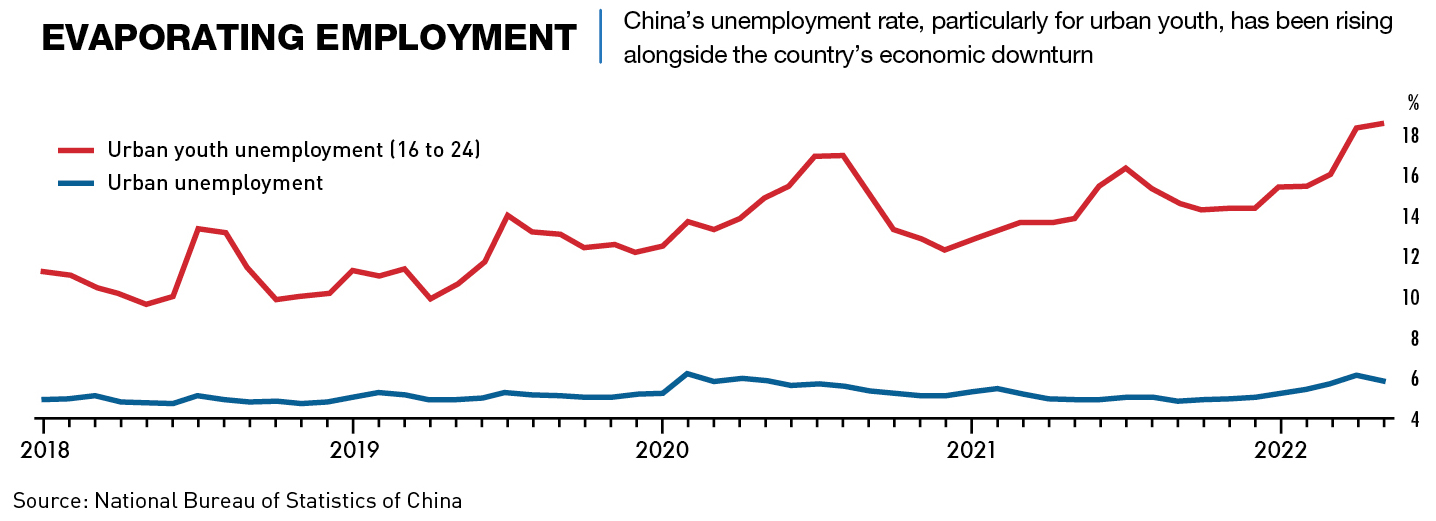

At the same time, there are record levels of unemployment among China’s graduate youth population, with nearly one in five young people out of work, according to official statistics. The youth unemployment rate reached 19.9% in July, far above the overall urban unemployment rate of 5.5%, and up 25% year-on-year. Graduates from rural areas face an even tougher time, they are significantly less likely to be employed than their urban counterparts. This situation is also far worse than in other major economies. For perspective, the youth unemployment rate in the US is 8.1%.

“There is a mismatch between the supply of college graduates and the market demand in China to some degree,” says Rockee Zhang, managing director of Randstad China Staffing and Outsourcing.

Although there are a vast number of open positions in factories, long-held prejudices around the quality or worthiness of blue-collar jobs make Chinese graduates reluctant to fill the vacancies. This has resulted in China’s seemingly contradictory state of simultaneous labor and job shortages, a paradox that has previously appeared in other labor markets around the world, particularly in recent years thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The market pressures in China were compounded in 2022 when a record 10.8 million graduates entered a cooling labor market. In addition, 2021 saw more than 800,000 Chinese students who graduated from universities overseas return home, further saturating the labor market.

The number of vacancies in companies looking to hire Chinese graduates actually increased by 8% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2022, but the number of applicants far exceeds this and is getting worse—the total number of applications grew by 75%. In mid-April, only about 47% of fresh graduates had received job offers, a substantial drop from nearly 63% in 2021.

The Chinese government has been promoting the country’s vocational colleges as a route to resupplying ailing industries and diverting people away from traditional universities. The sector is expanding, with 2,492 technical colleges in China at year-end 2021, 100 more than two years ago.

The number of new enrollments in higher vocational colleges did increase, but still fell 1 million short of the total available roles they would be expected to fill, and not all vocational graduates are continuing into the roles they are training for. Despite government efforts to boost promotion, the proportion of students in vocational education is actually down overall, with only 35% of students in vocational schools in 2020, down from 60% in 1998.

Rapid expansion

The current imbalance in China’s labor market is in many ways the result of the rapid expansion of Chinese higher education since the 1980s when the government initiated reforms to support China’s transition from a fully-centrally-planned economy to a more market-based economy. In 1993, the Outline for Education Reform and Development in China report emphasized the need for decentralized operations and management of academic institutions.

Today, China has the biggest higher education sector in the world in terms of total enrollment and degrees awarded every year. In 2020, a total of almost 42 million students were enrolled in 2,738 higher education institutions in China.

While the country now has a large supply of graduates, there is a gap between the skills universities are providing and the skills that industry needs. China produces around two million more STEM graduates per year than any other country, but there is a dearth of manufacturing workers and engineers in particular, which is worsening the pressure on China’s factories.

Chinese people generally attach great importance to education as a means of improving their self-worth and economic prospects. But education for the sake of education may not be the right move. “There’s a lot of educational inequalities across China, both in terms of availability and quality,” says Margit Molnar, head of the China Desk at the OECD’s Economics Department. “Many prospective students are not discerning enough about the quality of the institutions they wish to attend.”

Molnar adds that Chinese graduates are also often more highly qualified than they are highly educated, pointing to a growing gap in quality between the handful of elite schools at the top and the majority of universities across the country. “The expansion of the tertiary education system also brought about the dilution of quality,” she says. “With so many young Chinese graduates entering the system, it’s impossible to maintain the same quality of education.”

The widespread perception among graduates that factory jobs are inferior to office jobs has been one of the major factors leading to the current the job market situation. Children are told from a young age to dream of becoming a scientist or work in business when they grow up, but none are encouraged to want to work in manufacturing.

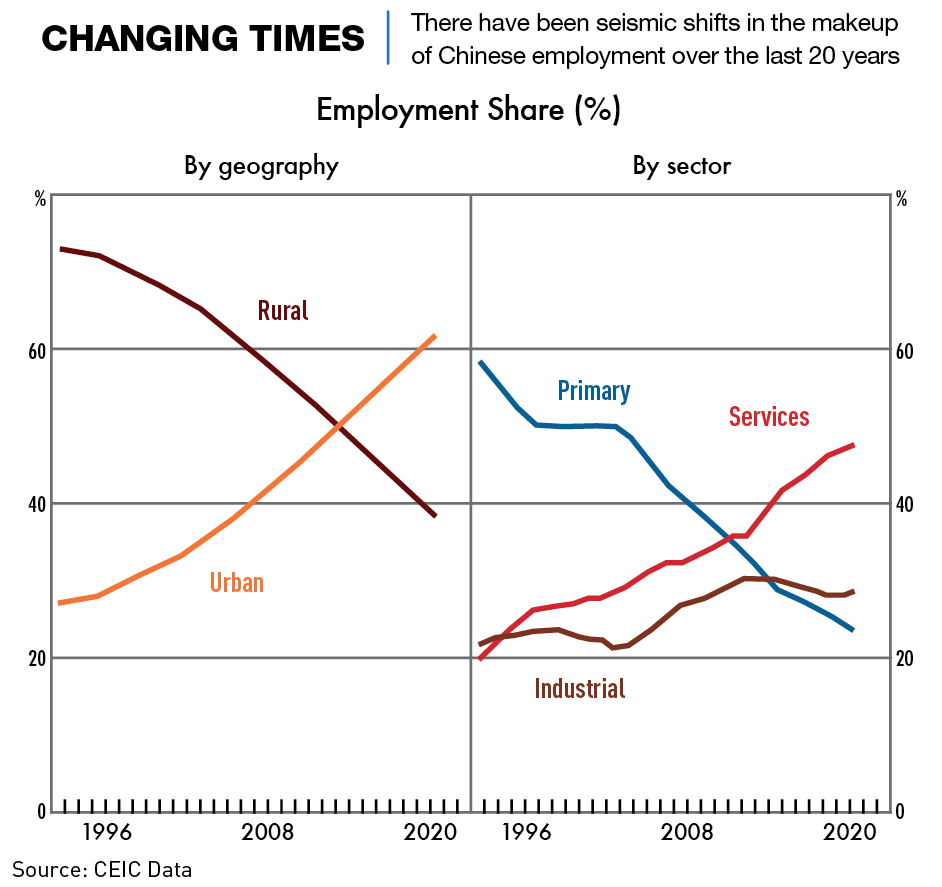

Economic reforms in the 1990s led to an increased portion of the labor force working in privately-owned factories, in sweatshop conditions, that led to an overwhelmingly negative impression of manufacturing work. Despite improvements in conditions and pay in the intervening years, many graduates remain unwilling to accept such jobs, having spent so much time and effort on their education.

But these manufacturing jobs have changed dramatically in the intervening years and, given the quality of education received by many of today’s graduates, there may need to be some concessions made.

“Graduate expectations in a tough job market are unreasonable,” says Julia Zhu, head of recruitment firm Robert Walters’ Suzhou office. “But the younger generation doesn’t want to compromise, and there is no real push factor for them to do so.”

Looking for work

Private sector roles were once coveted by Chinese graduates, but faced with a scarcity of jobs, many are now interested in the more stable, albeit lower-paid, positions in the country’s civil service.

According to a survey by the Chinese job-hunting website Zhaopin, some 11.4% of the newly minted graduates in 2022 were looking for jobs in the civil service, double the proportion from the year before. But again, these positions are highly competitive, with about 1.6 million applicants sitting 2021’s national civil service examination, in a scramble for only 25,726 jobs.

Meanwhile, the percentage of graduates seeking jobs at Chinese state-owned enterprises has increased to 42.5%, from 36% in 2021. Others are considering careers in medicine or education because of the stability provided to those roles thanks to their being government funded.

The graduate employment problem has been exacerbated by strict lockdowns in major Chinese cities. Beijing’s zero-COVID strategy diminished companies’ ability to absorb new staff. “A lot of companies are cutting headcount in China because of the supply chain shock from the coronavirus lockdowns,” says Julia Zhu. “This is a tough job market for graduates.”

In addition, over the past two years, the government has launched a regulatory crackdown under the common prosperity initiative that has hit the value of technology companies, which until recently were significant employers of Chinese graduates. Chinese tech giants including Alibaba and Tencent have recently conducted widespread layoffs, according to media reports, further enhancing the appeal of more stable civil service jobs.

On top of this, the crackdown on the tutoring industry, in an attempt to ensure equal access to education, wiped out many jobs last year, adding pressure to an already tight labor market. The sector has shed tens of thousands of jobs, with one group, New Oriental, sacking 60,000 staff. Graduates and young people have been disproportionately impacted, as many worked as after-school tutors.

Furthermore, an increase in automation in the private sector has to some extent offset the labor shortage in the manufacturing sector but has also worsened the problems facing young people, as it is expected to lead to job losses. According to the McKinsey Global Institute, up to 31% of working hours in China will be automated by 2030.

“The introduction of artificial intelligence and robotics into the manufacturing sector has very important implications for the youth unemployment rate,” says Feng from Peking University. “These digital technologies are expected to replace many workers because they can increase productivity on the factory floor.”

A top economic priority

Outgoing Chinese premier Li Keqiang has made the stability of the graduate employment market a top priority. The country is aiming to enroll 1.4 million students at technical colleges in the coming academic year, up from 1.09 million last year.

While many university leavers are unemployed, vocational college graduates are in high demand. Last year, 97.2% of them were employed, although not necessarily in their areas of expertise.

To make vocational training more attractive to high school students, some Chinese provinces including Shandong and Zhejiang now enable them to skip taking the grueling national Gaokao college entrance exam and go straight into higher vocational education. This is done through the newly introduced Zhongkao, a high school entrance exam taken at age 16, with many who fail ending up in vocational education.

China has the world’s largest workforce, numbering close to 900 million people, of whom 350 million are migrant workers. But digitalization and automation mean that many millions of people will need to reskill and sometimes change occupations entirely.

“Overcapacity in traditional industries, transformation, and upgrading of automation has led to more laid-off workers in some fields,” says Zhang. “But in the short term, the vocational skills of these workers do not meet the needs of re-employment positions.”

Some of this can be attributed to a lack of quality in the courses themselves. An example is 29-year-old Fu Hetong, who works for an energy company in Shanghai and is doing a Classic Coffee Making course for which he will be fully reimbursed by the government once he finishes. “I have no plans to become a full-time barista. I’m just doing it for fun,” says Fu. “The curriculum is not suitable for today’s specialty coffee trends anyway.”

McKinsey estimates that up to 220 million Chinese workers may need to transition into a new job by 2030, and this will require a lot of retraining. The government wants to ensure that China’s entire population has the skills it needs for a post-industrial economy. In mid-2019, it pledged the equivalent of about $14.8 billion to upskill the workforce through subsidies and a large-scale training plan in which 50 million people will receive vocational skills.

“China’s next phase of economic development is inseparable from the upgrade of industry, which in turn requires the cooperation of education,” says Liu Jing, professor of accounting and associate dean at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business.

Access to training is especially difficult for China’s rural-urban migrants, who numbered 291 million in 2019 and could grow to 331 million in 2030. China’s Hukou household registration system restricts access to training programs for many migrants, who are especially susceptible to job losses caused by automation because they tend to work in low-paid and low-skilled jobs. But some provinces have relaxed residency rules for recent graduates, helping them to settle in cities like Shanghai and access training and expand the local talent pool. The city of Zhengzhou has recently scrapped Hukou registration hurdles altogether.

Reflecting fierce competition for talent in some fields, employers are approaching graduates who have the correct skills up to two years before their graduation dates, helped by sweeteners from the government. “Employers who take on fresh graduates can get subsidies, tax breaks and easier loans,” says Zhu from Robert Walters.

Many employers have also strengthened their ties to vocational colleges through apprenticeship programs and mentorship schemes that help colleges better understand demands for skills and improve the design of training and strengthen pathways to employment.

In addition, larger firms are retraining graduates once they are employed, to address mismatches between skills and job requirements. McKinsey says the number of corporate “universities” is rising as employers retrain workers to improve productivity.

Many other countries such as Singapore have used immigration as the solution to the problem, especially in the construction sector. An analysis by the World Economic Forum suggests that, even with a stronger vocational training system, at least 4.95 million migrants would be needed annually in China to fill labor shortages.

But the likelihood of this happening in China is extremely small because of government restrictions on immigration.

In some sectors, technological advancements have helped ease various staffing problems. The Chinese working-age population has shrunk by more than 5 million in the past decade as the birth rate fell, worsening the shortage of labor. With wages also rising, many companies have begun to automate jobs in factories, warehouses and the transportation sector as they cannot find enough people to fill them.

“As the population ages, the phenomenon of re-employment in retirement may increase,” says Zhang.

No easy solutions

China now has a glut of unemployed graduates, with universities churning out far more degree-holding workers than the slowing Chinese economy can absorb. And while many are seeking shelter in civil service jobs as the private sector has been battered by COVID lockdowns, many graduates still aren’t willing to work on factory floors, where there are so many unfilled vacancies.

“Even in the coming years, for young people, the situation looks very grave,” says Peking University’s Feng. “There is still an oversupply of young labor but there aren’t the jobs to match the growth.”

Reskilling for millions of workers is required, and the Chinese government is encouraging the expansion of vocational schools and courses, to varying degrees of success. But ultimately, without a change in the national psyche around the perceived superiority of university education and a private sector or civil service job over blue-collar work, the labor mismatch in the country will continue to exist.

“With the qualifications they have, many graduates believe they have the right skills to match the jobs that they aspire to, but that isn’t necessarily true,” says Molnar. “This has built a perception in many that they are now at a certain level and blue-collar work is now beneath them. This is quite wrong, and a serious issue that China needs to deal with, in order to deal with their labor problems.”