As China shifts to a new economic model, the New Normal is used to describe this supposedly more sustainable economic growth. But what does it really mean?

Until recently, Zhengzhou probably felt like China’s future. The capital of the inland Henan province has been on a construction binge over the past dozen years, building out to become the heart of hinterland China. The largest high-speed train station in the world opened on the eastern boundary in 2012, burnishing Zhengzhou’s credentials as a transport hub. Zhengdong district, completed in 2013, is larger than the rest of the city put together.

Zhengzhou built itself up by gorging on investment and debt. Now development has slowed in tandem with the rest of China. GDP growth fell to 9.6% in the first half of 2015, an improvement from 9.3% in 2014 but down sharply from an average of more than 13% in the past decade.

Zhengzhou is confronting the ‘New Normal’, a stock phrase used by President Xi Jinping while touring the city of 9 million people last year. In recent months, it has become a near-ubiquitous mantra for Chinese officials. The problem is there have been no attempts to define the slogan, and Beijing has been happy to leave it vague.

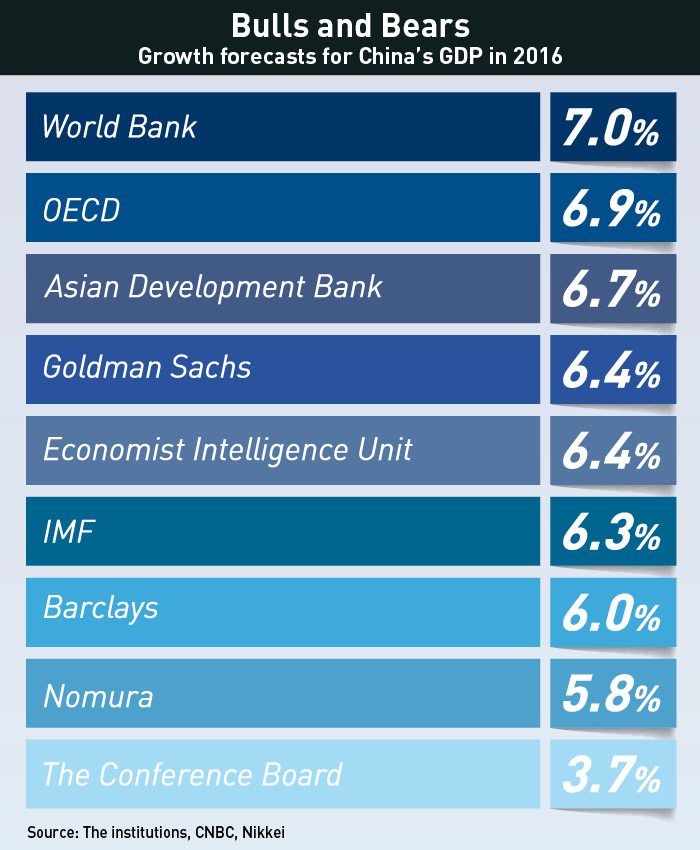

“Xi just talked about China being in a New Normal and there was no attempt at describing it,” says Michael Pettis, Professor of Finance at the Guanghua School of Management at Peking University. “It just doesn’t have any meaning… but I think most people assume the New Normal means growth of 6-7% is what we can expect for the next several years.”

New Narratives

China watchers generally echo that view. Gone are the days of double-digit growth. The consensus now is the New Normal will usher in a steadier, stronger, more sustainable economy led by consumption and services. So the slogan is intended to refocus the minds of officials on the quality of growth instead of quantity, says Michelle Lam, a Hong Kong-based economist at Lombard Street Research in London.

China’s economic data, from trade figures to manufacturing and services PMI, have been weak for months, belying the reassuring optimism espoused by the New Normal and making it increasingly difficult to believe the leadership’s mantra. That is reviving longstanding worries over the trustworthiness of China’s statistics and its true growth. Lam believes the world’s second-largest economy has now entered a critical period in its post-crisis adjustment, posing serious risks for the rest of the world. “The sharp growth slowdown… [will] be a stern test of Beijing’s resolve to reform in coming quarters,” she says.

Other analysts believe the New Normal goes beyond the economy, to portend a retrenched market environment—one potentially less hospitable for private and foreign businesses.

David Hoffman, Senior Vice President Asia and Managing Director of the China Center at The Conference Board, says a characteristic of the New Normal has been a U-turn from the market orientation supposedly championed by the Communist Party two years ago.

“What we’re seeing is a tightening of controls on the emergent market forces that now are active in China, after years of incremental opening. These market forces are not being allowed to play a more decisive role in the economy,” says Hoffman, citing as an example the state’s quick and heavy-handed containment of the stock market crash this summer, and the ongoing state support for over-capacity industrial sectors.

“In our view, the New Normal business environment is one that is more tightly controlled, less open to market influences, and for those reasons, a more difficult operating environment for Western multinationals,” says Hoffman. He pins the pullback from market forces on fears of economic instability. Subjecting China’s acutely overbuilt and uncompetitive industries to real competition from Western and private domestic firms would undoubtedly usher in a wave of ‘creative destruction’—a cornerstone of capitalism, whereby the market delivers innovation and productivity growth by forcing out inefficient players.

But creative destruction is likely seen as being more harmful than helpful, says Hoffman. China is in a tug of war between “markets and masters”—that is, using markets to drive growth and innovation, or relying on government-led economic engineering to do so.

That does not bode well for foreign firms. Their independence from the state and well-honed competitive instinct make them a wildcard.

“The investigations on product quality and safety, on tax evasion and on monopoly practices are designed to curb multinationals’ influence and competitiveness in the Chinese market, in aggregate, and are all a byproduct of these tensions between market forces and non-market forces,” says Hoffman.

A Painful Transition

When Xi used the phrase in Zhengzhou last year, fears were mounting over a slowdown in the Chinese economy. American and European demand had not recovered to support Chinese industrial growth. Worse still, disappointing imports were signaling weaker domestic demand at a time when China was vocal about the need to shift the economy away from an export and investment-led growth model to one driven by internal consumption.

“Growth rates had been slowing significantly and, for a long time, people didn’t really expect it. They thought that there’d been some sort of model that China had created that was capable of generating very, very rapid rates of growth,” says Pettis.

That view began to shift in mid-2014. “There’s a big debate about how much China’s going to slow. People even think the Chinese economy is going to collapse. I think the context of the New Normal is concern about the sustainability of the Chinese economy and the government is trying to build confidence by saying we’ve more or less bottomed out.”

Appetite for Consumption

A core component of the New Normal mantra has been a long overdue shift in the growth model, away from debt-driven investment and exports to consumption and services. Until recently, investment accounted for at least 50% of China’s GDP. Nowhere was this more evident than in the construction binge that has taken place over the past six years. In Zhengzhou, for instance, thousands of workers are racing to finish a second terminal and runway for the city’s airport by December, just three years after construction broke ground.

The government faces two formidable challenges: raise the proportion of consumption in GDP—58.4% in the first nine months of 2015 from 50.2% in 2014—and slow down debt expansion.

The tasks are intertwined because slower debt accrual would weaken growth in investment, which risks damaging the economy and creating a surge of unemployment. Pettis says that to mitigate this risk, China has “got to get consumption up in order to smooth this transition away from debt and investment.”

So there is some relief in the fact consumption remains a bright spot in the economy. The Chinese public have shrugged off the gloomy outlook by opening their wallets, with retail sales of consumer goods in October rising by 11% over last year—the highest growth rate so far this year. And a recent consumer confidence index from ANZ and Roy Morgan found nearly 43% of respondents reported being better financially off in October than a year ago, compared with 16.9% who felt worse off.

Unlocking more consumption will involve expanding demand for tertiary services like healthcare, education, tourism and financial products. To do that, policymakers will need to first bolster the household share of income and reduce the country’s national savings rate—which stood at 50% of GDP in 2013, according to the World Bank. Lam says the bulk of household financial wealth is tied up in interest-bearing deposits, so freeing up deposit rates will transfer income from firms to households as savers get rewarded properly.

Manufacturing Turmoil

China’s slowdown has been self-imposed through its rebalancing act. But an unexpectedly sharp decline in some areas of the economy over the past year—partly due to weak global demand—sparked fears of a more serious slump.

The problem has been exacerbated by Beijing’s insistence on sticking with high growth targets—7% for 2015—and the resulting reliance on credit to produce the output needed to hit that goal. Pettis says that because the credit system has been designed around implicit state guarantees, a large portion of financing is misallocated to the less-efficient, highly indebted economic sectors.

The New Normal narrative has been damaged by recent trade and market developments. Economic growth is weakening in a way not seen for years, with a deceleration to 6.9% in the third quarter—the slowest since early 2009 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. A series of surveys have pointed to contraction in the manufacturing sector—Caixin’s purchasing managers’ index slumped to a six-and-a-half year low of 47.2 in September—while a severe slump in the real estate market has deprived local governments of land sales, their main revenue source.

Evidence has mounted that the government lost some control over the economy. The meteoric rise and then crash of the stock market over the summer left investors rattled, but what was worst in the eyes of many was Beijing’s reaction to the turmoil. An unprecedented government intervention to prop up plunging share prices was criticized as heavy handed and ended up discrediting China’s equity markets.

While the stock market was roiling, the Chinese central bank carried out the biggest devaluation of the renminbi in two decades. That jolted financial markets and renewed fears of a ‘currency war’, while sowing more doubt over the health of the Asia’s-largest economy.

Another shock has been the belated effort to resolve local government borrowing and misspending. The National Audit Office’s first attempt to estimate the size of local government debt uncovered a stock worth 26% of GDP at the end of 2010. It was 32% of GDP in mid-2013, and the latest study by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences showed debt had jumped to 47.5% of GDP by the end of last year.

These slew of problems have prompted more bearish takes on the economy. Most independent forecasters have cut their outlook for growth this year to between 6% and 7%. Lam from Lombard Street Research says, “It is difficult to see growth above 3-5% in Q4 and 2016 as the correction of China’s massive overinvestment is now underway in earnest.”

The impact of the slowdown and restructuring pressures have been especially acute in China’s coalfields and old industrial bases. The coal-dependent province of Shanxi shrank 4.7% in the first six months of this year from the same period a year earlier. The three rustbelt provinces of northeast China have also been hit particularly hard—Heilongjiang contracted 4.2%.

The challenges confronting these provinces reflect what China is also facing nationally—curtailing the power of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), allowing market forces to play a greater role and finding new drivers of growth now that the infrastructure and housing boom is arguably tapped out. Structural changes are desperately needed, but hard to swallow for regions that flourished under the old Soviet-style command economy.

The question for policymakers is how to implement changes in Heilongjiang and elsewhere without causing greater pain and upheaval. A failure to adapt to the New Normal could see them left behind, as reforms such as increased environmental oversight and SOE restructuring accelerate their decline.

That would not be so terrible, argues Hoffman, who points out that having cities and provinces grow at different speeds arguably makes China’s development more “normal” in international terms. One unusual aspect of China’s rise is that virtually all its cities grew rapidly over the last decade and more, rather than a mix of peak performers and stragglers.

But a looming productivity crisis resulting from the overinvestment will mean “China doesn’t have a cohort of 650 cities all growing at above-average rates”, says Hoffman. “If you think about it, this makes China more normal. In the US, we’re used to a Silicon Valley and a Detroit. So is all of Western Europe. This is actually very normal.”

Labor Pains?

The economic slowdown that China is experiencing would lead to a higher unemployment rate anywhere else, as companies downsized or went bust. But China has defied that assumption as its official jobless rate has held rock-steady at around 4%—though it did tick up for the first time in recent years between the second and third quarter and unofficial figures put the number higher. But Lam argues the New Normal is likely to have had minimal impact on labor markets so far for three reasons.

Firstly, China’s demographics have helped the economy rebalance toward consumer spending. A shrinking migrant population and labor force—caused by the end of surplus rural labor and an ageing population—has helped raise incomes. Secondly, a buoyant internet-based service sector has emerged to employ more people per unit of output than manufacturing and heavy industry. Lastly, local officials have been subsidizing SOEs to avoid layoffs that could cause instability.

But Lam believes the New Normal’s impact on employment will begin to tell soon. “Our labor market conditions index suggests that the labor market has now finally started to feel the chill from feeble demand. The next 12-18 months will be critical to assess whether faltering job growth and rising unemployment stir social discontent and, if they do, whether Beijing will keep its cool,” she says.

As growth disparities set in across the country, Hoffman believes China’s ‘migrant miracle’—the unprecedented flow of labor from countryside to city that underpinned the country’s transformation—will ramp up in years to come. “Just like the Bay Area or New York attract jobseekers from all over the world, similarly, the cities growing more powerfully here will draw on a talent pool around the region to relocate.” This will accelerate the regional growth disparity to some extent, as it will create brain drain in the cities that migrants are leaving.

Reform Reckoning

At the heart of the New Normal is an old idea—reform. Overhauling China’s economy to put it on a sustainable path has been discussed for years, but the government ignored the calls in favor of short-term growth objectives. That stubbornness appeared to subside two years ago when the Communist Party unveiled sweeping plans in November 2013 that ranged from a relaxation of the country’s strict one-child policy to the scrapping of controls over interest rates.

Implementation has fallen far short of expectations, however, and Pettis believes this should not come as a surprise. “Historically, these types of reforms are very difficult to implement,” he argues, pointing out only democracies or high centralized autocracies—such as China under Deng Xiaoping—tend to be successful. He pins the failure to reform on the huge vested interests—Chinese groups that risk losing power—that have been sharply criticized by the leadership for resisting reform.

“This whole issue is a political issue more than anything else,” says Pettis. “Economically, they know what to do. If you look at the reforms proposed in 2013, they’re more or less the right things. The problem is they’re politically very hard to pull off.”

Reform is becoming more urgent, especially now that China’s previous, investment-led growth model has run its course. Persistently weak global growth and an overvalued renminbi mean exports will not drag China out of its economic mire, and Beijing can no longer throw money at unproductive investment without inflating domestic debt. Non-financial debt, including shadow banking and the grey economy, already reached 240% of GDP last year, according to Lombard Street Research.

Outsiders have very clear ideas on how China should reform, but whether their prescription matches Beijing’s is another question. Foreign governments and multinationals may be banking on greater liberalization and a more open market, but some analysts believe Chinese-style reform is about making the state a better business performer.

“What we see is a lot of effort—so-called “reform”—to perfect the way the state sector operates—to make it more productive, efficient and stable through non-market means,” says Hoffman. “What we don’t see is a lot of reforms that would let markets drive productivity and competitiveness.”

This year’s continued economic weakness, coupled with rising financial distress and some policy missteps, have renewed the debate over whether China faces a hard or soft landing.

But that is a fundamental misreading of the situation, argues Pettis, who says the options are not soft or hard. Instead, he envisages China undergoing either a ‘long landing’—growth rates falling by 100-150 basis points annually—or a more painful scenario, whereby growth does not dip but debt grows so rapidly the country hits debt-servicing capacity. “Then you will get what people will call a hard landing, but it will be a very hard landing,” says Pettis.

Hoffman concurs. “We don’t believe that China has soft-landed in a ‘New Normal’ 7-8% range. Instead we think China is on a long, slowish descent, has been for several years now, and is already at a much lower rate of growth than the official numbers suggest.”

That may not be music to the ears of China’s officials or the more Panglossian analysts, but it does suggest the New Normal will not lead to the crash landing or apocalyptic collapse predicted somewhat gleefully by doom-mongers. Xi and other leaders may have left the terminology up in the air, but, pending reform, they still have a chance of landing somewhere in the middle of these two contrasting outcomes.