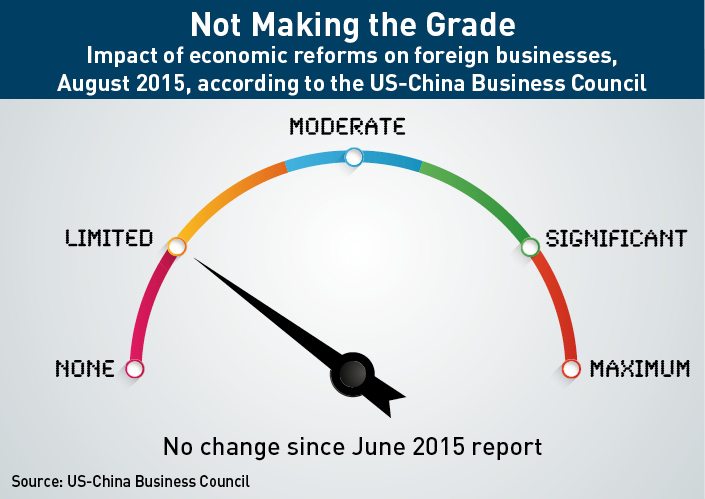

Over two years on from the landmark Third Plenum which outlined China’s reform blueprint for the next few years, just how much progress been made?

Traffic jams in China have become something of a YouTube staple. From the sudden appearance of paralyzing city gridlock when no one is prepared to give way, to the 100 km holiday-weekend nightmare caused by just too many cars. Both are, of course, a consequence of China’s rocketing, decades-long development trajectory, a failure to adequately adjust the rules, along with the simple fact of China’s vast population.

China’s longstanding reform program has arrived at much the same point. The enormous impact on growth of joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) has now largely played out, and the path towards developed economy status—while avoiding the so-called middle income trap—depends upon careful management of an extensive program of economic reform. In November 2013 at the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee, a grand total of 60 reform proposals were outlined, affecting almost every aspect of the economy.

“It’s kind of extraordinary that they were so ambitious,” says Kerry Brown, Professor of Chinese Studies and Director of the Lau China Institute, King’s College London. “But you’ve got to move beyond promises… when you make so many promises, you get people’s attention, and they wonder when the delivery is going to happen.”

Bold Intentions

The Third Plenum, however, is not the whole story. Brown contextualizes it as a “broad political commitment” which can only be assessed in relation to an associated “explanatory statement” issued by Xi Jinping himself, indicating 11 core priorities within the 60 proposals, which Brown summarizes as “absolutely orthodox Deng Xiaoping standard reforms… to deliver a sustainable economic model, to continue to have SOEs (state-owned enterprises) as the backbone of the economy, but to introduce, through the market, new ideas and new ownership models.”

Without the explanatory document, Brown views the Third Plenum communiqué as “a difficult document to interpret or make sense of beyond demonstrating elite political will” essentially leading up to the 13th Five Year Planning cycle; that is, ultimately, “the implementation document”.

That said, the key elements of the Third Plenum document will be familiar to most China watchers: the need to ensure the market plays a decisive role in resource allocation while conceding an important influence for the government on the management of the economy. The need to “work on the problems of an underdeveloped market system, excessive government intervention and weak supervision.” The desire to “promote reform by opening up.” It introduces the broad issue of land reform although this receives less prominence in Xi Jinping’s explanatory statement. Then there is the question of anti-corruption, which appears alongside general comments about strengthening the rule of law.

The communiqué is a long document, but the word that appears more often than any other is ‘reform’ itself, leaving observers with unanswered questions about the eventual detail. “From a macro perspective… [the] reform agenda… is very broad and principles-based and doesn’t contain details against each specific area,” says a senior, Beijing-based business consultancy source who wished to remain nameless.

Indeed, the same source suggests the frequency of the word ‘reform’ may disguise the absence of actual reform in the detail: “Without making reference to specific policies it can leave people wondering what area of reform we need to carry out. [Leaving] interpretation in the hands of whoever is in charge.”

The importance of the document therefore must reside in the principles it outlines, rather than the absent detail, which await clarification in the small print of the 13th Five-Year Plan. Nevertheless, the Third Plenum has always been viewed as a key moment in China’s periodic cycle of administration, and this last occasion was the first chance the current leadership had to set out its stall.

But in doing so, the leadership inevitably raised the stakes of reform and ensured they will be judged on its outcome. “The government is always chasing people’s expectations,” says Brown, and the people expect “the things that have been promised.”

There is no question that the ideas, if not yet the detail, outlined at the Third Plenum point to some very radical changes for the Chinese economy. Transforming a formerly communist—and still strongly state-lead—economy into one in which the market plays a key role in the allocation of resources is not simply a question of flicking a few switches. Headline macroeconomic plans towards internationalizing the RMB and opening up the capital account catch the attention of international markets, but most economists think the more urgent, and inevitably more difficult, tasks center on making the domestic economy more productive and more competitive, ultimately able to withstand direct international competition without the protective intervention of the state. And it is the area of SOE reform that attracts the most immediate skepticism.

Andrew Collier, Independent Macroeconomist and Managing Director of Orient Capital Research in Hong Kong, says of much heralded SOE reforms: “Recently there’s been a lot of noise about significant reforms, but I haven’t seen much progress. We’ve seen some mergers of some large state firms, but… most of those are in peripheral sectors or are… ways to avoid debt problems.”

Leslie Young, Professor of Economics at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, broadly concurs. “State enterprise reforms haven’t gone that far,” he says, although he puts this down to a question of priorities, suggesting that without immediate reform “nothing terrible is going to happen. [Xi Jinping] has just got higher priorities, like cleaning up the military.”

Young adds that there is much misunderstanding in the West of just how government works in China. “The implementation of the plan has been not so much prioritized in the technocratic sense or in terms of an economic analysis of priorities, but in terms of personalities,” he says, adding, “It is just the way things work in China.” He goes on to say of SOEs that “there is a vast, loose power structure… that is capable of hedging and fighting back”, neatly describing the hazards of confronting vested interests within a government characterized by complex personal entanglements.

Steady Progress

Nevertheless, despite the macro-level skepticism and the absence of detail so far, some do see progress, particularly in the area of innovation, but also on those SOEs not perceived as central to China’s notion of state-lead capitalism. Song Gao, Managing Partner at PRC Macro Advisers in Beijing, takes the view that “they have done a lot to encourage… innovation and… entrepreneurship.” Equally important, they have been active in “streamlining the government approval process”, all of which is significant from a supply side perspective. Song believes that “the Third Plenum reforms are more about the supply side”, reinforcing what he describes as the emergence of a “New Supply School or Theory” attributed to Xi Jinping.

Collier also stresses developments in the technology sector, with the emergence of companies such as Alibaba as key examples, but suggests this is largely a consequence of longer-term shifts in investment patterns, rather than directly related to the reform program. “There has been an inexorable rise in private investment over the last 20 years… you could argue that there has been a de-facto privatization going on regardless of the power of the large state giants.”

Moreover, Song suggests that so far, because the Third Plenum reforms are focused on the supply side, “the first two years” have prioritized laying “out the overall structure and direction, putting the legal framework in place.” Eventually SOEs will be divided into two types: “One will be for public services or SOEs in natural monopolies” and the others “classified as commercial SOEs or operating at a local level, will eventually be let go. Not privatization, but more like ‘public-ization’. They will be allowed… to diversify their shareholding… between private investors, SOEs and even local governments.”

Roadblocks

There are, however, important reasons why progress has been slow in this area. Like the holiday traffic, the sheer numbers of SOEs are staggering. There are estimated to be over 150,000 in China, regionally distributed, and attached to all different parts of government. “Even the State Council’s research department has about 10 SOEs. They are the mastermind of all the reform proposals, and they are supposed to be neutral… but they still have a conflict of interest,” says Song. “This will be a very slow process.”

Then, when considered abstractly, the question of valuation is no small matter, given the staggering stock market fluctuations seen last summer and in the New Year. This, CKGSB’s Young believes, is a regrettable distraction. “A collapsing stock market in Germany, in South Korea and the US means big trouble and… big wealth effects. But the proportion of Chinese holding stocks is relatively low, so the wealth effects are not anything like as significant.”

Moreover, he argues that “China doesn’t have law in any meaningful sense. Absent law, if you were to push the SOEs into market reform and the shareholders have no legal rights and you don’t have an independent judicial system, what you’ll have is Russia.”

Then there is the inevitable conflict of interests within the government itself, which like the sudden city gridlock, results from legislative gridlock as different centers of authority refuse to give way. Song suggests this is because “there has been a lack of consensus at the very top of the political spectrum about which direction these reforms should take”, a tension which can only be exacerbated by slowing growth and market headwinds. Song further argues that the main tension exists between the Ministry of Finance, which “controls … the central SOEs”, and the SASAC (State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council), which directly oversees the SOEs.

Further Afield

Another important area of reform concerns rural land rights, announced in an effort to improve land use and rural productivity in a time of rocketing food imports. Currently rural land in China is collectively owned and farmers are unable to exchange their rights for any financial benefits. This produces many constraints on economic development by tying workers seasonally to the land in order that they secure the meager returns available, while dis-incentivizing investment to improve the land over time. It also has the effect of preventing more rapid urbanization as farmers lose their small farming rights if the land use changes, prompting them to resist development due to a lack of adequate compensation.

In early 2016 this aspect of the Third Plenum reforms was announced again by Finance Minister Lou Jiwei, but there are still many question marks over how it will proceed, with pilot schemes in the more advanced provinces seen as most likely. Unfortunately, the structural resistance to these reforms is likely to be even greater than that over SOEs as the point at which the legislative gridlock will occur is already one of the key political intersections in China; that between local and central authority.

According to Collier, “local government derives anywhere from 40% to 80% of their revenue from land sales.” Song adds that the “central government is reluctant to allocate more tax incomes to local governments”, which places the issue into the wider context of very difficult fiscal reforms, with Song describing “this stalemate between the central and local fiscal reforms” as “a big hurdle.”

On these reforms, Young reverts to his point about the absence of meaningful law. “There’s no question that privatization and transferability [of rural land] is a definite plus because it permits aggregation and scale economies…. But you can’t predict that the legal, political, democratic structure will be powerful enough to provide an alternative safety net.”

Lastly, Song believes that on the question of land reform, “assigning property rights to farmers touches the bottom line of Chinese political commitments.” He nevertheless thinks there are some potential advantages from assigning partial rights for land usage, although these are still shrouded with reservations concerning the precise impact this will have on the economy, hence still some way off.

On the question of macroeconomic reforms China is perceived to have made some important progress on the Third Plenum aspiration of ‘opening up’. A signature step has been taken towards the internationalization of the RMB with its acceptance as part of the IMF’s special drawing rights (SDR) basket of currencies, and the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) is widely seen as a key initiative attracting considerable international backing, which will foster greater, state-directed capital investment overseas.

Once again, however, not everyone is convinced. “There is way too much praise given to those two reforms,” says Collier. “The SDR was symbolically very important for Xi Jinping, but I think from a financial and macroeconomic point of view it’s not that significant.”

Song regards the achievement of these two milestones more positively, noting “a prevalent view among the top leaders that the RMB’s inclusion into SDR is considered at the same level of importance as China’s accession to the WTO.” But he suggests that the ground for these reforms was prepared long before the Third Plenum, hence they are not necessarily a good measure of Third Plenum progress.

What Xi Wants

The one area of the Third Plenum reforms where obvious progress has been made, at least in terms of overall activity, is in the anti-corruption drive. This is not often thought of as an economic reform exactly, but it has become commonplace to see the assertive centralization of authority under Xi Jinping as a prelude to deeper reforms.

“There’s no doubt that Xi Jinping has more power than previous political leaders,” says Collier. He adds, by way of an explanation for the lack of progress on economic reforms, that “[Xi’s] focus is on politics, not on economics.”

Kerry Brown similarly views that “the leadership have had to create the political space to cut against vested interests… and they’ve being doing it incrementally by the anti-corruption struggle.” Furthermore, he notes that “creating a new consensus is never particularly easy.”

On the other hand, Brown also cautions against too much emphasis on Xi Jinping’s power, stressing that “the power of Xi Jinping… is of no use if it cannot deliver the very fundamental things that people are looking for in terms of the quality of their lives and the quality of the economic returns [from the reform program]”, raising the important question of what happens if the reforms do not proceed as outlined.

“With a falling growth rate and… no real sign of political reform [the question of] what people are getting for supporting the Third Plenum reforms is going to start becoming more urgent.”

Young, however, has an intriguingly different interpretation of the ongoing centralization of authority. Believing that “absent law” there is nevertheless a pressing need to “tighten the discipline and integrity of the process by which… officials are managed, supervised and rewarded.” And this “alternative form of corporate governance… is the [Central] Commission on Discipline and Inspection”, or the institutional form of the anti-corruption drive.

Young adds an important codicil with the view that the stock exchange in China is not only different from other stock exchanges around the world, but is actually a “mistake”. “To have private share ownership by Mrs Wong who does it by feng shui, it just creates a political liability… you [do not create] a market for corporate control.” What you have instead is “random redistributions of wealth, often [from] people who can’t afford it.”

All of which informs his view that the institutional mechanism of the anti-corruption struggle is itself a key economic reform, rather than a prelude to others, and it is not a temporary measure, but is here to stay. In short “where the SOEs are not subject to the market for corporate control, they are subject to an organizational discipline through the party.”

The question of success or failure of China’s Third Plenum reforms inevitably falls into the Zhou Enlai category of ‘too soon to tell’, but according to Kerry Brown “we have a lot of knowledge of the framework, we have a bit of knowledge of the particularities, and in a few months we will know much more detail.”

Young also urges the need to take a longer view, avoiding what he terms the “knowing sarcasm” informed by misunderstanding governance in China as purely a question of power. “[The leadership] have correctly addressed the most critical issue—corruption was becoming intolerable and to privatize more SOEs, and even [carry out] land reform, that can wait for another five years.”

Brown, however, is less sanguine about the timeframe, believing that “the people’s expectations in China are… very high.” He adds that “the government contract with them is not being met, they’re just being given a lot of empty promises for tomorrow and they want something today.”

All of which leaves China in the unenviable position of needing to clear the reform logjam, or see the arrival of a more prosperous future fade further and further away. As Brown says, “They now really need to be about delivery, not just about promises.”