Having conquered China’s smartphone market, Xiaomi now wants to take over your living room—and the world

Achieving a $45 billion valuation is an immense feat for any company. To do it within four years and without achieving significant recognition outside of your home country is an even greater one. Yet that is exactly what Xiaomi has done. Xiaomi, an upstart internet company that has generated fervent fandom in China, is now poised to shatter the longstanding image of Chinese tech companies abroad.

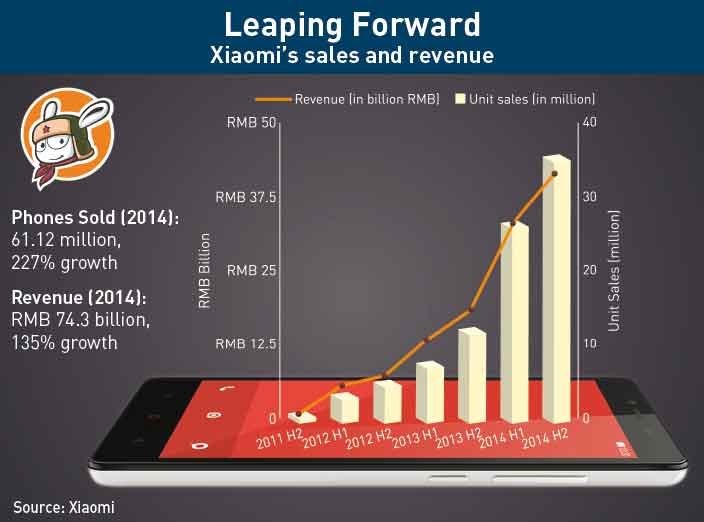

Founded in 2010, the company has since leapfrogged more established competitors such as Samsung and Lenovo to become China’s top smartphone brand (at least for a time), until Lenovo’s acquisition of Motorola, the third-largest smartphone brand in the world by shipments, all the while eschewing the standard tactics found in the sector.

But the company’s approach goes beyond the smartphones with which it made its name, and it is now making its first forays into the much heralded ‘Internet of Things’. It is off the back of this that Xiaomi achieved the $1.1 billion funding round that gave the company its mega valuation, and among the investors were the Singaporean sovereign wealth fund GIC, DST Global and Yunfeng Capital, a private equity firm co-founded by Jack Ma, Alibaba’s Chairman. That $45 billion valuation is greater than that of Lenovo or Uber, the world’s other hotly tipped start-up.

For all this, the company is now entering its trickiest phase yet as it branches out internationally and beyond its traditional smartphone base. Will it manage the transition and can it export its China success?

The Spread of Xiaomi

Xiaomi’s meteoric rise is reflected in the company’s rapid increase in its valuation, up more than 10 times from $4 billion in June 2012. Overseeing this growth has been co-founder Lei Jun, now Xiaomi’s Chairman and CEO. He has played a significant role in drawing attention to the company and cultivating the diehard fandom amongst consumers that has been a key plank of the company’s success. Comparisons are often made to Apple’s inspirational founder Steve Jobs due to Lei’s at times similar appearance and presentation. Lei has previous experience too in the worlds of tech and commerce having previously been the CEO of software company Kingsoft and founder of Joyo.com, an e-commerce site that was later acquired by Amazon. He has also become one of China’s leading angel investors, with the online retailer Vancl being one of his investments.

“He’s made himself very visible as a tech entrepreneur, as a very successful person in China,” says James Roy, Associate Principal at China Market Research Group. “He’s a figure because of his success and his company’s success as a Chinese company in a field that’s has been much more dominated by larger international companies… and that’s viewed by a lot of Chinese people, especially young people, as an inspiring thing.”

Beyond Lei’s celebrity, Teng Bingsheng, Associate Professor of Strategic Management at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, identifies “three pillars” to Xiaomi’s success. One of these has been its smartphones featuring high-end specifications, yet coming at prices significantly cheaper than their competitors. “They positioned their phones nicely,” he says, noting Xiaomi’s ability to compete with China brands on price, while still maintaining quality levels that are closer to the top end of the market. “For the money… you get [a] cell phone that’s probably 80 or 90% of the functionality of an Apple iPhone or a Samsung.”

While still primarily sticking to this strategy, in January the company made its first foray into the premium price segment when it unveiled the Xiaomi Note, the Pro version of which retails for RMB 3,299 ($530). Jingwen Wang, a research analyst at Canalys, thinks that this could be a successful move as Xiaomi’s existing users develop more disposable income and wish to differentiate themselves more.

The second factor in its success is its strategy of selling directly to consumers online, making particular use of flash sales as a way of generating buzz and scarcity. This also has had the effect of lowering the company’s costs by eliminating the need to maintain retail stores, the savings from which can be significant. “In China, the costs for the [retail] channel are particularly high and inefficient. Companies oftentimes have to give out 30% of the total revenue just to their channel,” says Teng.

The third pillar is its strong social media presence, which it has used in lieu of traditional advertising, again a cost-effective strategy. According to confidential documents seen by The Wall Street Journal, in 2013 the company spent just RMB 876 million ($140.9 million), 3.2% of revenue, on sales and marketing.

“Marketing methods that have been used by traditional industries are a thing of the past in the internet age,” said Lin Bin, the company’s president, in an interview with the Nikkei Asian Review. (The company said it was unable to answer questions from CKGSB Knowledge.)

This social media focus has also fed into the company’s product development, with the company routinely incorporating feedback from customers into future updates, further strengthening the bond with consumers and helping to give rise to so-called ‘Mi fans’. Through the company’s social media forums “[Xiaomi] will understand their consumers and quickly react to improve their software,” says Ivy Jiang, a research analyst at Mintel.

Taken together, these elements have catapulted Xiaomi to the top of the smartphone market in China.

“[An] affordable product with [a] high configuration, understanding the consumers’ needs, as well as quickly reacting to improve their software, I think that’s what’s made Xiaomi the top smartphone brand in China right now,” says Jiang.

The conventional understanding of Xiaomi’s business model is that it sells its phone almost at cost as a way of directing consumers to where it really makes its money—software and services. But despite the low margins, the documents seen by The Wall Street Journal showed that Xiaomi was still able to make a net profit in 2013 of RMB 3.46 billion ($556.8 million) from revenues of RMB 27 billion ($4.3 billion), with 94% of its revenue coming from hardware sales.

Nonetheless, this drive towards services plays an important role in Xiaomi’s attempts to create stickiness, and is key to understanding the next steps in Xiaomi’s strategy, evidence of which we are now beginning to see. Its wildly successful smartphones would likely not be sufficient to justify Xiaomi’s high current valuation, and the key to understanding what does back it up lies in the ecosystem the company is rapidly creating.

One Device to Rule Them All

Already Xiaomi has branched out into other devices beyond the smartphone including a smart TV, air purifier, TV set-top boxes, routers, headphones, wearables and even a light bulb. All of which is just the start, with other household consumer goods soon to bear the Xiaomi brand. This is part of the company’s ‘100 Xiaomis’ strategy that seeks to apply the lessons of its smartphone devices to other product categories.

To that end, the company has invested in a wide range of companies. In December, Xiaomi invested $200 million in home appliances maker Midea, while Xiaomi’s light bulb and air purifier were designed by the start-ups Yeelight and Zhumi, respectively. Lei Jun has said that Xiaomi has invested in 25 start-ups.

But more than just representing expansion into new areas as the company grows, these partnerships and investments are about creating a full ecosystem. As such, they represent the firm’s desire to fully participate in the so-called ‘Internet of Things’, with a Xiaomi smartphone lying at the heart of an array of devices. For example, the company’s air purifier can be controlled through an app, with pollution readings and notifications of when to change the filter being sent to the user. And in January the company unveiled sensor panels for its smart home ecosystem.

“Xiaomi is now building an ecosystem through these investments and extending its business coverage to not only smartphones, but [also] to the whole smart home, and even some related hardware devices,” says Jiang.

All of which serves to enhance loyalty and stickiness among its users as they buy into that interconnected Xiaomi ecosystem. Xiaomi’s Android-based MIUI operating system that comes with all Xiaomi devices and which is also freely available for non-Xiaomi phones, plays a core role in tying all these elements together, as well as enabling access to Xiaomi content and services.

Teng compares this to how other brands have created worlds for their followers to “live in”. “If you enjoy motorcycles then you may want to live in the world of Harley Davidson—they have everything surrounding you with the Harley logo,” he says. “Xiaomi [has] a similar strategy. They’re confident that whatever they do, their true fans will follow and buy the product. So the product itself doesn’t need to have significant differentiation… with the Xiaomi logo, with this social media frenzy I think they’ll be able to achieve significant sales regardless of what they do, at least in the short term.”

This fandom and devotion is particularly relevant given Xiaomi’s youthful demographic. Analysis by the mobile analytics firm Flurry shows that Xiaomi’s users skew heavily towards business professionals under the age of 34. Not only is this a fast growing segment of consumers with significant spending power, but it is also one that is coming to a point where home ownership is a likely occurrence, and complete set of interconnected devices from a brand they have loyalty to will be an obvious choice when kitting out their home.

Beyond hardware, Xiaomi has also moved to position itself as a future hub for content. An investment in Youku Tudou in November 2014 for an undisclosed stake and value saw the creation of a strategic partnership between companies, which will allow Xiaomi to act as a gateway to entertainment content and also see the company participate in content production.

Not satisfied with its attempts to conquer the home, Xiaomi is also casting its gaze beyond China’s borders, in particular towards emerging markets. Overseen by Hugo Barra, Google’s former Vice President of Android Product Management, who was hired in 2013, Xiaomi initially made its way into Singapore in February 2014 before entering India, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines later in the year. Brazil and Russia are the next candidates, according to Lin Bin.

These emerging markets are the places where the next wave of smartphone growth will occur, and it is particularly important for Xiaomi to harness that growth as China’s smartphone market matures. Moreover, Jiang points out that consumers in these emerging markets are more price sensitive. Smartphone growth in these countries is primarily directed at cheap devices—according to IDC, in 2013 nearly half of all smartphones sold in India cost less than $120.

But here Xiaomi has had to diversify its approach, in some cases eschewing its direct selling approach, at least initially, and instead partnering with local vendors. In the case of India, it has teamed up with the country’s leading e-commerce site Flipkart, although it now also sells its phones through its own site, and has even made its smartphones available in brick-and-mortar stores. What hasn’t changed is the company’s commitment to flash sales and social media, with Xiaomi making use of Facebook and Twitter as well as its own message forums.

Fertile Ground?

Xiaomi has worked hard to create an ecosystem that locks in consumers, but its success in this regard is by no means assured, and history shows plenty of former mobile phone giants—from Nokia to Motorola to HTC—who have fallen by the wayside.

“With the MIUI software, I think Xiaomi has already successfully made a lot of its young users invest money in it, so it means that even in the future if they want to transfer, all this money has been wasted,” says Wang of Canalys. “That will be helpful to increase its brand loyalty.”

But youth, Xiaomi’s main demographic, are notoriously fickle and there is no guarantee of Xiaomi’s status being maintained.

“If they keep doing what they’ve been doing, this can be sustainable for a while. But I think in three years they have to come up with something new, something that continues to get people excited, because young people, their focus can shift very quickly,” says Teng. “If there is something emerging in the economy… then it’s possible that Xiaomi might lose that cutting edge image. I think this is a big threat.”

Zhang Zehua, a 22-year-old student, is a Xiaomi user. “I have used the product for a year now, I would say that I kind of like it. But like other electronic devices, they change too fast—I don’t think I will use it for long,” he says, adding that he would consider other, non-Apple brands when buying his next phone.

Wu Yunrei, a radio DJ in his twenties who isn’t a Xiaomi user, is not convinced by the company’s phones. “I wouldn’t choose Xiaomi in the future, because I don’t think it is good quality, at least some of my friends say so after they bought one,” although he admits he would consider other Xiaomi products, such as its air purifier, because of Lei Jun’s status and influence. “I want to see his ideas and creativity.”

Rivals imitating its tactics might also be a threat, and Lenovo and Huawei have or are planning to introduce products aimed at young people backed with internet-driven marketing—Huawei has said it sold 20 million Honor smartphones, its handsets range that competes with Xiaomi.

Meanwhile, the company OnePlus boasts its own competitively priced, yet high-spec smartphones.

Teng thinks that this might prove to be a threat to Xiaomi, but it will be hard for any company to entirely mimic what they’ve been doing, particularly older phone companies that are still firmly tied to traditional business models, and social media buzz is not easy to create. “[Xiaomi] has a nice combination,” he says. “[They] will still have a sustainable edge in the next few years.”

Wang agrees: “In 2015 Xiaomi will continue to face all these kind of threats, but maybe they cannot be called too strong challengers.”

But Xiaomi’s international expansion has already hit stumbling blocks—in December, an Indian court ruled that Xiaomi had to suspend its sales in the country after Ericsson brought a patent complaint against it, although the ban was partially lifted until January 8.

Xiaomi possesses very few patents—in China the company has made use of patent licenses pooled by the chipmaker Qualcomm—and Wang, Jiang and Teng all identify this as being a major sticking point in the company’s international moves.

Localization also presents a challenge. “The real challenge for Xiaomi is whether they can understand the local consumers’ needs,” says Jiang, while Roy points out Xiaomi’s need to engage with foreign consumers on an emotional level if the company is to succeed. “How do you create fans, how does that work?” he says.

Wang also stresses the need to cater to consumers on their own terms, saying that localization of the MIUI operating system will be crucial, and she also points out that having the right talent in these countries will play an important role.

But if Xiaomi’s expansion throws up some difficulties, it is nonetheless in pursuit of aims that will ultimately strengthen it as a business. By constructing a rich ecosystem and utilizing social media-driven marketing, it stands to maintain a brand loyalty that has eluded all phone companies except Apple, and its policy of targeting emerging markets represents a prudent decision based on these countries’ growth prospects and Xiaomi’s own strengths and weaknesses. However, it is this international expansion where Xiaomi is weakest—its position in China is strong, but the tactics that have got it there will be much harder to recreate abroad.

(To read about other companies in China trying to emulate Xiaomi’s success in smartphones, please click here.)