E-commerce has been growing exponentially and occupying market share previously dominated by physical stores. What does this mean for the future of Chinese retailers?

Whether they live in a metropolis like Shanghai or an out-of-the-way town in the countryside, the e-commerce revolution over the past few years has touched almost all Chinese consumers—an order on JD.com doesn’t discriminate between customers in the biggest cities or the smallest towns. All but the most remote villages can get their packages within a few days.

Prices, too, are generally lower online, begging the question as to what advantages physical stores still have over their powerful online counterparts. The booming figures of e-commerce giants show a world in which they are driving consumption growth, and are even responsible for making cultural activities evolve.

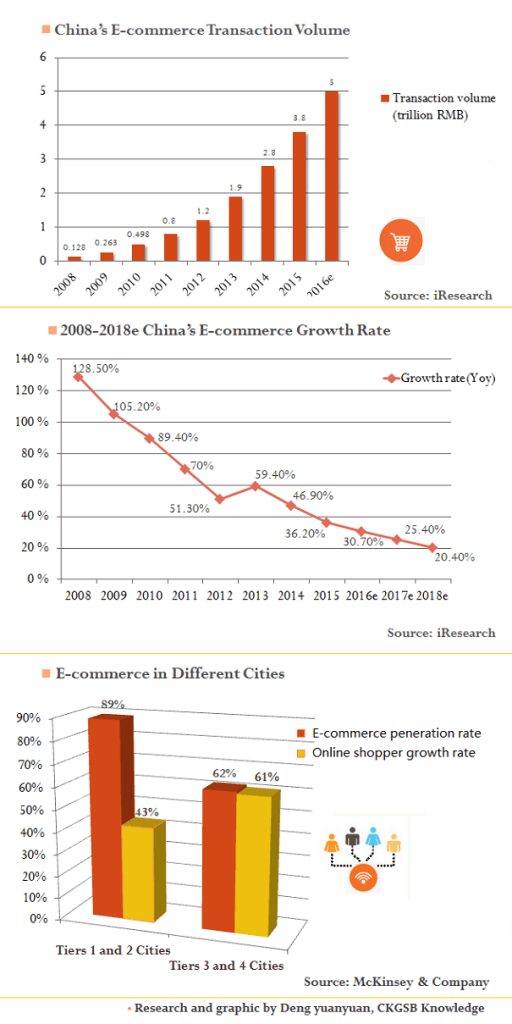

Alibaba’s Singles Day Sales have become an annual event for Chinese of all ages, while cross-border e-retail companies are bringing Black Friday and Boxing Day discounts to China. Figures from iResearch reveal that in 2015, the transaction volume of e-commerce was 3.8 trillion, almost 30 times higher than the same number seven years earlier. Even everyday grocery items are increasingly being bought by customers sitting at home, using a smartphone.

So will e-commerce keep growing and wipe out online stories entirely? The answer was once blurry, but is now growing clearer. To really examine this, we need to go back to a case study from five years ago.

In 2012, Alibaba founder Jack Ma and Wang Jianlin, the CEO of Dalian Wanda Group, bet on the future of China’s ecommerce—Wang was bullish about the offline business, he stood firm in his belief that e-commerce wouldn’t replace physical retail. And he was right. Despite the growth of the e-commerce market, it represents about 10% of all retail sales.

So what is happening to the other 90%?

New Retail

After the incredible speed of e-commerce growth in recent years, it seems to be slowing down.

One reason behind this is the high penetration rate. By 2016, 62% people in Tier 3 and 4 cities were shopping online, while the number in Tier 1 and 2 cities stood at 89%.

Consumers in China have also changed over time, now the middle class are shifting their money from cheap products to premium services and goods where experience and recognition ties take priority. Beijing based IT engineer Derek Wu says he doesn’t want to order online and wait for a couple of days for a better deal. “Buying Lego technic in store costs more than buying from a substitute buyer on Taobao, I checked both prices then bought it in store,” he said, adding that he didn’t want to delay having fun.

A McKinsey report also pointed out that shopping malls are also where two thirds of Chinese consumers choose to go with family. “Every time I go home I spend two or three days shopping with mum. It’s not that I can’t get those clothes elsewhere, it’s because we enjoy shopping together and we talk a lot,” Rachel Mi, a college student who goes to her hometown twice a year, told CKGSB Knowledge.

Integration

“Online-only won’t survive, all businesses need to integrate online and offline resources,” Wang Jianlin said to media not long after his half-joking bet with Jack Ma. Wanda, who profit most from its commercial property, have attempted to develop an e-commerce platform Feifan to better serve its malls.

Jack Ma also brought up this “New Retail” concept on various other occasions. At the 2016 Computing Conference he made the clear point that there wouldn’t be “e-commerce” in the future, instead, there would be a form of “New Retail”.

Yintai runs the high-end Intime fashion malls in tier one and two cities. In 2014 Yintai received 5 billion RMB in investment from Alibaba. As a listed company on the Hong Kong stock exchange for ten years, Yintai is now seeking a deal in which Alibaba takes its ownership of Yintai up to 74% for RMB 17.7 billion.

It’s no coincidence that Alibaba and Yintai are looking at this merger—the two companies collaborated during the 2016 double-11 festival, when Yintai unified its online and offline prices and saw sales in physical stories increase by 48.8% compared to the previous year. In addition, Yintai’s online platforms sold RMB 41.8 million worth of goods.

Uniqlo is another example of a company merging their online and offline operations. During the 2016 November Singles Day event sales, it demonstrated what “New Retail” actually means.

After being the bestselling brand on the Tmall Double-11 (another name for Singles Day) festival for three years in a row, Uniqlo blazed a new trail this year. On Singles Day at 11’o clock, the Uniqlo Tmall store announced that all stock for the online platform had sold out, but customers could still purchase it in brick-and-mortar stores with the same discount as online stores. This move saved much by way of logistics expenses and shortened customer’s waiting times.

Another record breaking sale was at BESTORE, a snack company with online stores on all mainstream e-platforms in China. A customer named Mr. Li, in Shenzhen, was the first person to receive his Double-11 order—only 11 minutes after he completed payment. As with most brands on Tmall, BESTORE did a pre-sale event before Double-11, in which customers put a down payment a couple of days prior to the Nov. 11th sale, then according to their location, BESTORE shipped products to its nearby stores. Once the second payment was complete, the closest store would send out the order to customers at the shortest time possible, in this case, 11 minutes.

But are these efforts really examples of integration of online and offline resources? Baozun, a company that provides e-commerce services for global brands told CKGSB that integration is not only an issue of logistics, but also a business issue.

Firstly, the branding of the stories themselves can be quite complex. A brand may have different kinds of stores across the country: some are franchise stores, others are direct-sales stores, and some are dealer-stores.

When operating franchise and direct-sales stores, brands can decide on promotions, product categories and link online orders to offline stores for faster delivery. But in the case of dealer-stores, the relationship with other stores can be fraught with complexity as they also compete with them and may conflicts of interest in terms of brand image. Brands sell to dealers but once sold, brands have zero control over dealers’ decisions.

Dealers don’t necessarily share customer information with brands and if those stores continuously give discounts, it can damage the brand image—people won’t pay the standard prices anymore.

And even with the franchise and direct-sales stores, there are concerns about management. Serving the consumer is the ultimate goal, but when an order comes from online channel and is allocated to a direct sales store, who should get credit for making the sale?

In Uniqlo’s case, there are plenty of reasons for their retail success. Uniqlo keeps products and prices unified in online and offline channels. With over 470 stores across China, people in many cities can feel and touch the product in person without worrying about product quality or whether they have snagged a good deal—and this is good for brand image: one key survey shows that even consumers who are likely to engage with brands both online and offline, the shopping experience in physical stores is always better and satisfaction levels remain higher.

Women’s apparel brand Inman is a very successful “Tao Brand”. The term Tao Brand refers to brands that built their presence on Tmall or Taobao, without physical stores. Now Inman is seeking outlets beyond Taobao. On May 2016, the sales from all of Inman’s physical stores reached RMB 20 million. CEO Fang Jianhua believes that contrary to what first impressions might indicate, a period when physical stores are seeing their presence shrink might be a good time to enter this market, as costs are lower. In fact, he believes that in third and fourth tier cities, costs might be lower than those of online channels—attracting consumers online has become much more expensive and difficult.

Take children’s shoes, for example. Sales volume in physical stores stands at 80%, but on online platforms it is now at 20%. “As prices unify both online and offline, the physical stores have much more potential in terms of sales and development,” said Huang Lipeng, general manager of children’s footwear company LixunKids.

But not everyone thinks the trend is to be followed. Hstyle, also Called Handu Yishe, is one of the most successful women’s apparel Tao brands. It has no plans to launch physical stores. High level managers of Hstyle have discussed their reasons for this in various media interviews. The number of customers a brand can reach to from online channels and offline stores is very different, and a lot of orders occurred at irregular hours of the day, when stores would not be open. They also say that online stores have more to offer in terms of promotion and discount.