China is determined to become a world leader in lithium batteries and electric cars. And Beijing believes it has found the key to dominating these strategic industries: gaining control of the global lithium supply

Chile’s Atacama Desert is one of the most inhospitable places on earth. Situated 2,300 meters above sea level and encircled by mountains, the region receives almost no rainfall and the blinding sun singes exposed human skin within minutes.

But this year, this remote desert is the center of a struggle for control of one of the world’s paramount emerging industries. Forty meters below the salt flats that cover large swathes of the surface lie our planet’s largest and purest reserves of the chemical element lithium.

Lithium, the lightest of all metals, has the best electrochemical potential. This makes it perfect for rechargeable batteries, a technology that powers our smartphones and is expected to become even more crucial in the future.

“Lithium-ion batteries underpin the fourth industrial revolution,” says Simon Moores, Managing Director of London-based resources industry research firm Benchmark Minerals Intelligence. “They are the key to breaking the world’s addiction to oil and unlocking not only electric vehicles, but renewable energy through energy storage.”

Demand for lithium is rising faster than for any commodity over the past century, according to analysts at investment firm Morningstar. Total global sales in 2015 totaled 175,000 tons, but by 2025 demand could reach 775,000 tons, Morningstar forecasts.

Supply is already struggling to keep up with skyrocketing demand, and the average price of lithium has more than doubled over the past two years. Leading technology companies—including Apple, BMW, SoftBank and Tesla—are scrambling to lock up deals with suppliers of lithium and other battery raw materials to insulate themselves from a future supply crunch. Tesla has even signed a deal with Australian mining firm Kidman Resources, which will not begin producing battery-grade lithium until at least 2021.

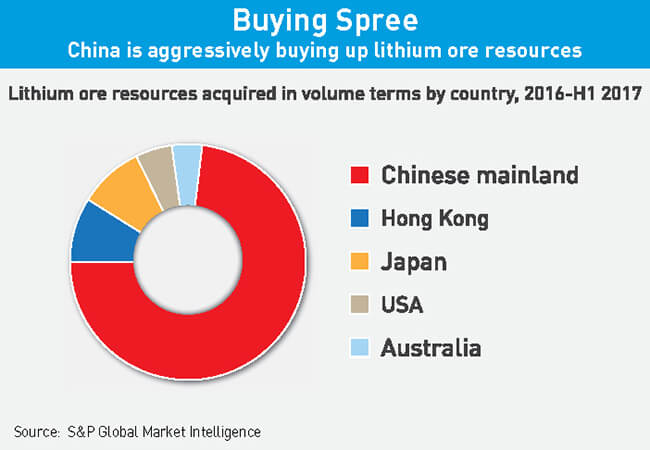

But the most aggressive movers have been Chinese companies. Between 2016 and mid-2017, Chinese buyers accounted for three-quarters of the lithium deals signed globally, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

China has the second-largest lithium reserves in the world, but most of the deposits are expensive to extract due to their low quality and location in high-altitude, remote regions. Chinese companies have therefore been snapping up higher-quality lithium resources, especially in Australia and Argentina, home to the world’s third- and fourth-largest reserves.

Now, Sichuan Province-based resources firm Tianqi Lithium is attempting to gain control of the Atacama’s reserves, which make up around 27% of global lithium resources. Tianqi is bidding to acquire a 25.9% stake in the Atacama mine owned by Sociedad Quimica y Minera (SQM), Chile’s largest lithium producer, for around $4.3 billion. The offer represents a 22% premium above market value, according to Reuters.

If the Tianqi-SQM deal goes through, the two companies would control nearly half the world’s lithium supply. Many analysts see the Tianqi-SQM deal as part of a Chinese strategy to control the global supply chain for lithium batteries. The market will be worth $93 billion by 2025, according to forecasts by research firm Grand View Research.

China also sees dominating the battery industry as crucial to its ambition to become a world-leading producer of electric vehicles (EVs). Made in China 2025, a Chinese government plan to transform China into an advanced manufacturing powerhouse, describes electric vehicles as a key strategic industry.

Tianqi’s offer has been accepted by SQM but could still be blocked by Chilean regulators due to fears the two companies would gain excessive power over the global lithium market. Santiago’s antitrust authority has until August to decide whether to probe the deal further.

But China is putting maximum pressure on Chile not to proceed with that investigation. Xu Bin, China’s ambassador to Chile, warned in April that a decision to block Tianqi’s investment would “leave negative influences on the development of economic and commercial relations between both countries.”

China’s anxiety to seal the deal is understandable. If current trends in the lithium market continue, the Chinese—who have nailed down access to the best and cheapest raw materials—could enjoy a significant competitive advantage in the battery and electric car industries. Yet, China’s multibillion-dollar bet on lithium could turn out to be a costly mistake.

Playing the Long Game

Beijing’s strategy of buying up raw materials for lithium batteries dates back to the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008, analysts say. The key resources it has focused on are lithium and cobalt, another metal that is used in the cathode (positive side) of a battery.

China’s economic planners saw that lithium batteries were becoming ever more important due to the increasing popularity of smartphones, electric vehicles and the transition to renewable energy. They set out to make China a dominant player in that industry.

But to do that, Beijing recognized that it would first need to gain control of upstream industries. The only way to make high-quality electric vehicle batteries affordable is to manufacture them at huge scale—as Tesla is doing through its Gigafactories. Making batteries at this scale requires access to vast amounts of lithium and cobalt.

“Dominance over the global lithium-ion battery supply chain would insulate China’s battery makers against a potential supply crunch and boost their influence over pricing,” risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft said in a March note.

In pursuit of that goal, China has gradually invested in and taken control of cobalt deposits in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where 65% of the world’s cobalt is mined, and built up a formidable refining capacity. China produced roughly 58% of the world’s refined cobalt last year, according to metals firm Darton Commodities.

“Now, the intentions are clear,” says Benchmark Minerals Intelligence’s Moore. “The foresight was incredible.”

Meanwhile, Chinese lithium chemical companies have been taking stakes in exploration stage lithium producers, according to Moore. Major deals have included Tianqi’s 2012 takeover of Australia’s Talison Lithium, then operator of the world’s largest lithium ore mine, for $815 million, and Ganfeng Lithium’s acquisition of a 43% stake in the Marion lithium project in Western Australia in 2015.

China has also taken control of the intermediate stages of the lithium battery supply chain. The country now produces 75% of the world’s electrolyte, 75% of its anode materials, 63% of its cathode materials and 45% of its separators, according to website Clean Technica.

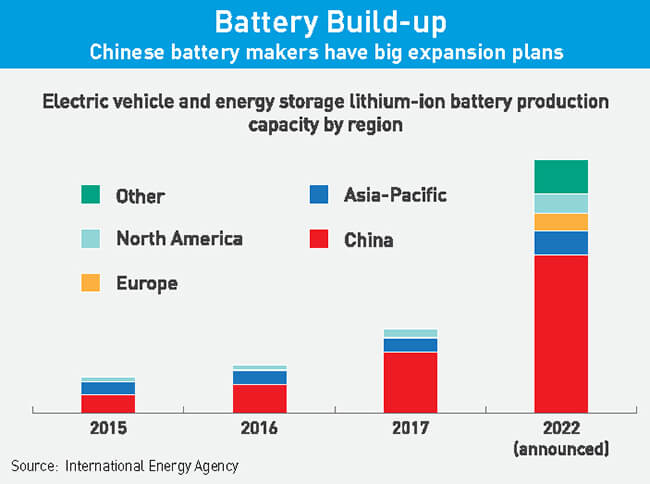

These foundations have helped China build out new battery making capacity at vast scale. Four years ago, there was only one lithium battery megafactory—a facility able to produce more than 1 Gigawatt hours of cells per year—under construction in the world: the Tesla Gigafactory in the US. Now, there are 40 worldwide, and over 50% of this new capacity is located in China.

“China needs the lithium: they are building EV and lithium-ion battery infrastructure on a scale that has never been seen before,” Moores says. “It is very much about supply over price and the long-term thinking is putting Western companies to shame.”

Panasonic was the world’s top EV battery producer in 2017, followed by China’s BYD and South Korea’s LG Chemicals and Samsung. But Chinese upstarts like CATL, fresh from a $1 billion initial public offering, are emerging as formidable players. As the Chinese players expand production at breakneck speed, overseas rivals are struggling to keep up, according to Moores.

“Established Japanese and Korean producers will still have a competitive edge in terms of quality in the near term,” he says. “But China will undoubtedly have leading companies at each level of the supply chain. For Japanese and Korean firms, it is about expanding while remaining competitive in terms of quality and cost.”

But this could be a challenge for the Japanese and Koreans if they struggle to access lithium at reasonable prices.

Demand Debate

China’s attempts to control the global lithium market raises geopolitical questions. If the road to lithium access one day passes through Beijing, could China use its near-monopoly as a weapon by denying foreign companies access to resources?

In the past, China has been accused of doing that with rare earths, the chemical elements used to make electronic devices. Beijing controls 85-95% of global production of rare earths, analysts estimate.

Lithium is so abundant that it would be extremely difficult for China to acquire a market share approaching 85%, according to Benchmark Minerals’ Moores. “China can become the world’s biggest buyers of the raw materials but there will be much competition from elsewhere as well,” he says.

But if China establishes a lower level of dominance, it could still hand Chinese battery makers an advantage, according to an Asia-based global auto company executive, speaking on condition of anonymity. “Chinese battery makers believe that controlling lithium supplies will reduce EV battery costs [by allowing them to determine prices], and give them a stronger competitive advantage,” says the executive.

Tianqi’s SQM investment could give the company significant power to set prices due to the Atacama’s massive reserves. SQM recently received approval to expand production, meaning that its output could more than treble to reach 165,000 tons by 2021, according to a forecast by Chinese finance firm Changjiang Securities. That is not far off the current total global lithium supply.

And if the lithium supply continues to tighten, the greater the strategic advantage in having access to the resources produced by SQM, currently the world’s lowest-cost lithium producer thanks to the purity of the Atacama brine.

The likelihood of a future lithium supply crunch is a subject of fierce debate among analysts. As noted, supply is struggling to meet demand, helping producers like Tianqi post massive profits. Yet lithium is far from a rare commodity. Lithium reserves outstrip annual production by 400 to one, according to data compiled by Bernstein Research. This makes the metal four times more abundant than cobalt and copper, whose reserves exceed production by a factor of 100.

A recent Wall Street Journal op-ed argued that China would never be able to control the lithium market because other countries could simply keep opening more mines. The writer suggests that even just in Europe, new mines could open in Germany, Portugal, Sweden, the Czech Republic and the UK.

Analysts at Morgan Stanley have forecast a 45% drop in lithium prices by 2021 due to the potential for massive increases in supply. But this forecast has been sharply criticized by others for both overestimating the potential for new supply and underestimating the likely rise in demand.

“I am firmly of the view that everyone, including Morgan Stanley, is grossly underestimating how quickly the market is moving on the demand side,” Ken Brinsden, CEO of Australia’s Pilbara Minerals, told Reuters in February.

“The mistake the mining analysts make is they think it’s like iron ore and other bulk commodities where you dig a big hole in the ground,” Duncan Goodwin, Head of Global Resources at Barings, told the Financial Times. “We can raise capital to bring on new supply but it’s going to be very, very difficult because of the nature of the product, which is very difficult to mine and process.”

Driving Electrification

China has a lot riding on this, especially considering the scale of investment it has made into electric vehicles and charging infrastructure. Beijing has handed out billions of dollars in subsidies to electric car companies over the past decade in a bid to become a world leader in the nascent industry.

A desire to reduce air pollution and carbon emissions is partly behind this embrace of EVs, but the primary driver is technological. The transition to electric offers China a unique opportunity to become a globally competitive auto manufacturing power. Most Chinese auto brands—with the exceptions of BYD, Geely and Great Wall—still lag behind foreign competitors, despite having had access to foreign technology via joint ventures for decades.

“Chinese automakers, especially state-owned companies, have been slow to develop solid brands and technology,” the auto executive says. “The powertrain [engine and driveline] of gasoline vehicles is holding them back: it’s the most difficult part to develop.”

In contrast, an electric induction motor is much simpler. “It produces direct rotational motion and uniform power output, is smaller and lighter, and doesn’t need a complicated transmission to connect it to the drive wheels,” notes Evannex, a seller of Tesla accessories, on its website.

“The Chinese believe they can quickly master the technology involved in an electric motor and leapfrog ahead in the global EV industry,” says the auto executive.

Whether Chinese EV brands like BYD and Nio (see page 53) will be able to supplant traditional auto giants is uncertain, but Beijing’s control of lithium could provide an advantage. The battery typically accounts for one-third of the cost of an electric vehicle, which means any savings in this area will provide a cost advantage.

If it establishes control over cobalt, lithium and nickel supplies, Beijing may achieve an ideal cost structure for the manufacture of entire electric vehicles, says Lu from TrendForce. “This will make the companies more competitive in the export of new-energy vehicles in the future,” he says.

Ford Chairman William Ford agrees. Speaking in Shanghai last December, he said: “It’s clearly the case that China will lead the world in EV development.”

If these predictions are right, the rewards for China will be enormous. Around 1.2 million EVs were sold globally in 2017, and that figure is expected to reach 10.8 million in 2026, according to a January forecast by BIS Research.

Fork in the Road

However, there is one wild card that could disrupt Beijing’s plans: the possibility of the widespread adoption of vehicles powered by hydrogen fuel cells instead of lithium-ion batteries.

Fuel-cell vehicles are superior to battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) in many ways. Whereas most BEVs only travel around 150 kilometers before needing to be recharged—a process that often takes hours—a fuel-cell vehicle can travel more than double that distance and be charged in under five minutes. As a result, fuel-cell vehicles are also eco-friendlier than BEVs.

“Fuel-cell vehicles take us out of the range anxiety problem, making them ideal for inter-city travel,” says Asad Mahmoud, an assistant professor of energy materials at South Korea’s Dongguk University.

At present, cost is the main bottleneck to wider adoption of fuel-cell vehicles. Toyota, one of the main proponents of fuel cells in autos, has sold just 4,000 of its Mirai vehicles since 2014. A Mirai retails for $52,500 in the US, compared to $30,000-$35,000 for a Tesla Model 3 or General Motors’ Chevy Bolt, Forbes noted in a December report.

If the cost of fuel-cell vehicles could be brought to parity with BEVs, the former could be a better replacement for the internal combustion engine, Mahmoud claims. “The driving experience with a fuel-cell vehicle is more like what people are used to with petrol cars,” he says.

Given the level of investment that has already gone into electric vehicles, a turn to fuel cells still looks a long shot at this stage. But if there were such a move, China would find that it had spent a decade subsidizing the auto equivalent of Betamax. “It would be a major setback,” says the auto executive.