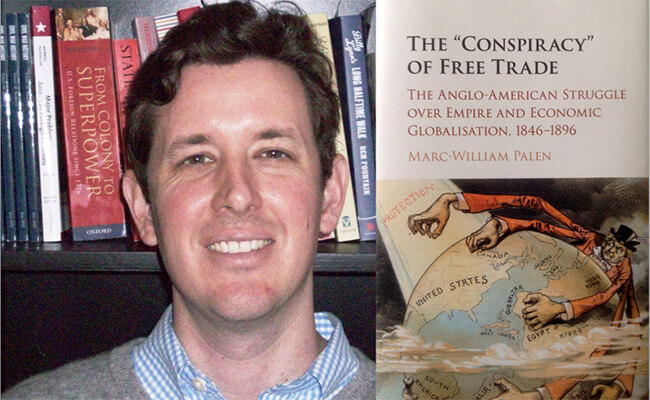

“Trade wars are easy to win,” says US President Donald Trump. US-UK trade historian Marc-William Palen disagrees. In this interview, Palen, author of The “Conspiracy” of Free Trade: The Anglo-American Struggle over Empire and Economic Globalisation, 1846-1896, and senior lecturer in history at the University of Exeter (UK), argues that US politicians’ pursuit of trade wars in the 19th and 20th centuries yielded mostly short-term political gains for themselves and high, long-term economic and strategic costs to their country.

Should we be surprised to have a conservative American president who is anti-free trade?

The Republican Party was not always the party of free trade and free markets; the so-called Reagan Revolution and the GOP’s libertarian love affair with Atlas Shrugged are very recent developments. If you go back to the Republican Party’s founding in the 1850s and onward, it was the party of protectionism, of big government serving the interests of big business.

Why were they so keen on protectionism?

They felt that if the industrializing US were to shelter its less developed industries from the big, bad British—who were, admittedly, more industrially advanced than the rest at that time—this would allow US “infant” industries to develop instead of getting undermined by less expensive British competitors.

But mostly they were motivated by a fear and hatred of the British that was palpable throughout American politics in the 19th century—in part because the memories of the War of 1812, and the British role in the US Civil War were still fresh, and in part because at this point, the British were top dogs, the global superpower. This also made them easy political targets. Particularly during election years, the Republicans would demonize Britain and its empire in a big way.

And that often meant Canada.

Of course, being so near the United States, Canada, as a contiguous British colony, was a common target.

The Republicans did very well electorally with trade wars and protectionist threats for a long time, but did it always yield the economic results they wanted?

The record is mixed. For example, one common side effect of protectionism is that it increased outsourcing. In the case of the Canadian-American trade conflicts, some American companies — Singer Manufacturing, American Tobacco, International Harvester, Westinghouse — realized that it would be cheaper to just move their production to Canada rather than paying the high tariffs that Canada had put in place: by the late 1880s, around 65 U.S. manufacturing plants relocated to Canada. But in the short-term, such trade wars also helped foster the US tin plate industry and the “Sugar Trust.”

Did the trade wars with Canada have any other long-run implications?

In 1890, the Republicans passed the highly protectionist McKinley Tariff. Many Canadians thought the US was enacting this tariff as a secret ploy to annex Canada and force it to become an American state. This led to a pitched political battle in the 1891 federal elections in Canada, between the Canadian protectionists— Conservatives who wanted to strengthen ties with the British empire—and the Liberals, who wanted US-Canadian free trade. It was close but the Conservatives won the election, with long-term repercussions.

So the conservatives won in the polls north and south of the 49th parallel, but practically speaking, who won that round of the trade war, Canada or the US?

Britain. The Canadians ended up developing closer trade ties with Britain for decades to come. It would take another hundred years to get Canadian-American free trade, culminating in the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement.

The trade war poisoned the US-Canada relationship in other ways, too. For example, there were secret plans drawn up by both Canada and the United States—on the books, so to speak, until the 1920s and 1930s—on what the countries were going to do if the other were to invade. This mutual suspicion remained in no small part because of continued economic tensions. Of course, trade wars don’t inevitably cause military conflict, but there’s a growing body of literature that suggests there is a strong correlation.

Did protectionism have any impact on American imperial aspirations at that time?

You can’t disassociate economic issues from America’s embrace of imperialism in the late 19th century, which culminated in the Spanish-American War in 1898. At the time, Republican rhetoric didn’t really make a distinction between political nationalism and economic nationalism. These became entwined. Only when you had a Democrat in office, during the two administrations of Grover Cleveland in the late 19th century, did you see a temporary retreat from this protectionist imperial project as Cleveland tried to reverse a lot of what the Republicans had done.

A lot of the imperial aspirations began with the economic crisis that ran from the early 1870s to the mid-1890s, a long depression that scared American manufacturers and farmers into thinking that the country needed new outlets for its surplus goods, while American bankers felt that they needed new customers for their surplus capital. And so the Republicans, being the ones in charge, oversaw this imperial acquisition of new markets for surplus goods and capital under a protectionist umbrella. That’s why, when the US acquired the Philippines, for example, really stringent protective tariff walls were put up around the Philippine Islands. Filipinos had to buy American goods, and then pay tariffs to sell their goods in the United States.

How about in the 20th century?

The Republicans were very good at utilizing economic crises alongside the bogeyman of “Free Trade England” to make the case for protectionism. But this all changed following the now-infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930. After the US raised duties on a swath of imports, Canada responded once again with tariff increases of its own. Much of Europe did too, and it essentially turned into what is now commonly thought of as the Smoot-Hawley tariff wars of the 1930s.

Let’s take Italy as an example. In the wake of Smoot-Hawley, American-made cars were attacked on Italian streets, and US car sales plummeted. Nor did the blowback end there. The American tariffs had unintended geopolitical consequences, as well; not only was there a massive decrease in American imports into Italy — $211 million worth of imports in 1928 fell to $58 million by 1932 — but the Italians turned from the United States to the Soviet Union. They signed a commercial treaty with the Soviets in August 1930, and followed this up two years later with a non-aggression pact. And of course, the Soviet Union was more than happy to have Italy as a trading partner because it remained an international pariah at that point.

So besides hurting American industry, the Smoot-Hawley trade war reduced US leverage with Italy, and helped drive Italy and the Soviet Union closer together. Is this kind of knock-on effect common in a trade war?

Trade wars often have this sort of unexpected, unpredictable geopolitical fallout. Just look at how Trump’s protectionism has already soured relations with America’s closest allies over the past couple months.

Which is why the Americans soured on trade wars after World War II?

After the Second World War, American protectionists were no longer able to win the ideological and political debate. For one thing, they could no longer blame Free Trade England because Britain had abondoned free trade in 1932. For another, Smoot-Hawley took the blame for worsening the Great Depression and creating geopolitical tensions in the lead up to the war. I think that’s why after the war, you see a very different Republican party start to take shape and widespread American support for trade liberalization.

Of course, it’s impossible to prove a negative, but do economists have a sense of whether protectionism slowed down US economic growth in the end?

This is a question that economic historians continue to debate: were these protectionist policies responsible for what is, by and large, a success story of America’s late-nineteenth-century rise to industrial dominance? Most economists say yes, the United States expanded, but argue it likely would have done so much more efficiently and effectively if it had embraced free trade instead of protectionism. However, there are heterodox views. For instance, in Kicking Away the Ladder development economist Ha-Joon Chang argues that protectionism had benefited early-nineteenth-century Britain, which only turned to free trade in the 1840s once its industries had matured, and that protectionism also served the US well until it became an industrial powerhouse in the 1940s and found it advantageous to promote free trade worldwide.

How about the strategic implications?

From an economic standpoint, the result of a trade war means higher costs for consumers. But the answer to how a trade war will fall out geopolitically is, I think, the big question mark. What’s remarkable (and, for many observers, worrying) about what’s going on now is that we have the United States, which oversaw the creation of the post-1945 liberal economic order, essentially being the first to signal the retreat from it. We can get some idea of the likely results from history, but because of the unprecedented nature, what happens next is anything but certain.