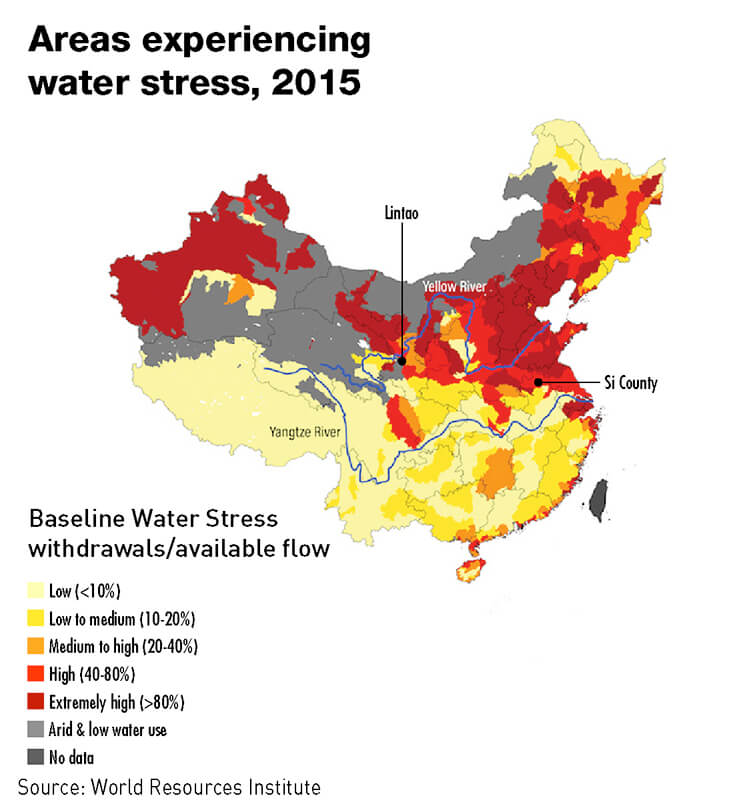

The moment finally came just after Lunar New Year, 2016. That morning, residents in Lintao, a city of 200,000 in the remote northwest, turned on the taps, but no water flowed. The groundwater that provided the town’s supply had simply run out.

A year later, Si County, a cluster of settlements 2,000 kilometers to the southeast, also ran dry. After municipal wells began to empty, local schools and hospitals resorted to drilling their own. But even private wells are often ineffective as the county’s daily water shortage has surpassed 20 million liters.

Hundreds of cities across China now face similar crises as the country’s rapid development takes a terrible toll on water supplies. Urbanization and industrialization on a massive scale have led to an enormous rise in water use.

In the north, which contains nearly half of the population but only 20% of the water resources, there is not enough to meet demand. Groundwater storage on the North China Plain fell at a rate of more than 6 trillion liters a year between 2002 and 2014.

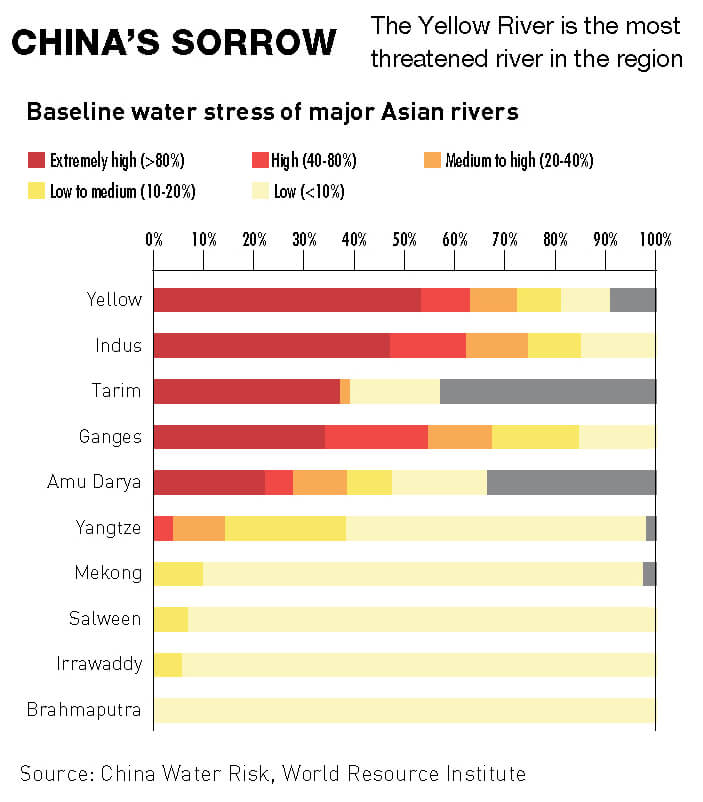

In 1990, there were 50,000 rivers in China. Now, there are only 22,000. Even the mighty Yellow River, once called “China’s Sorrow” due to the devastating floods it unleashed, is a shadow of its former self. Flow has fallen so much that the river often fails to reach the sea.

Former Premier Wen Jiabao warned in 1999 that the growing water crisis could be a threat to the “survival of the Chinese nation.” Many analysts agree.

“These problems are massive. You wouldn’t expect any government to easily solve them,” says Charles Parton, a former British diplomat in China and Associate Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) think tank.

Drastic Measures

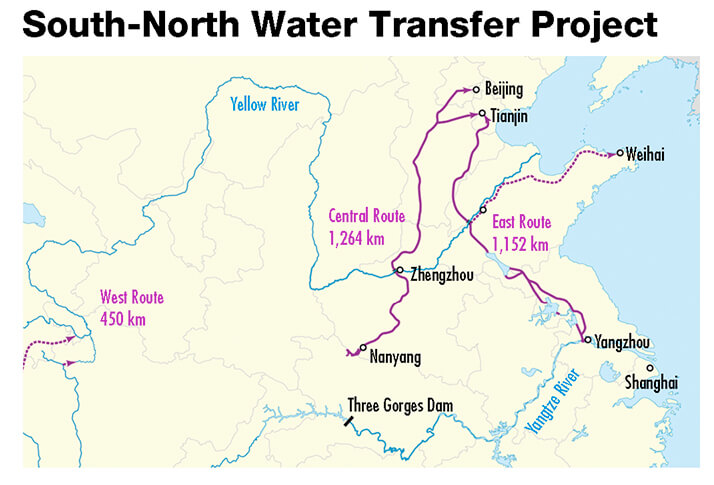

A large part of the government’s response so far has been to tackle the problems with grandiose engineering projects like the South-North Water Transfer Project. This vast network of canals, which has already cost a staggering $62 billion, is designed to provide relief to the parched capital, Beijing.

As Beijing’s population swelled to more than 20 million, the city resorted to overusing groundwater to meet demand. Reserves are now being emptied so rapidly that the city is sinking more than 11 centimeters every year as aquifers collapse, according to satellite radar observations. The per capita water resources of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, home to some 112 million people, are lower than the per capita annual consumption of Saudi Arabia, a country of 32 million people which, unlike China, can afford the energy resources to desalinate, according to Parton.

The first phase of the project was completed in 2014 and now delivers billions of tons of water from the Yangtze River to Beijing. As a feat of engineering, it is impressive, but critics argue that the project will only provide temporary relief. The capital still has an annual shortfall of 400 million cubic meters of water and continues to rely on pumping groundwater. The Economist, with trademark snark, labeled the canal system a “massive diversion.”

Other proposed fixes appear more outlandish. Officials in Gansu, the arid province where Lintao is located, have suggested transferring water 2,000 kilometers from Siberia. Other ideas include shipping vast quantities of snow across the country or storing river water so that it is not “wasted” by flowing into the ocean. Technology for a rain-seeding network that could one day cover an area three times as large as Spain is currently being tested in Tibet.

While these projects might bear fruit, a long-term solution will need to tackle the skyrocketing demand for water, as well as increase supply. Luckily, the government has already taken many steps designed to do this, although these efforts have so far received little attention from the media.

“In the last five years, China has completely reframed how it manages its environment,” says Debra Tan, Director of China Water Risk, a Hong Kong-based nonprofit research organization. “This year, the government entrenched the concept of ‘ecological civilization’ in the constitution.”

Like many phrases coined by the Chinese Communist Party, there is debate on the meaning of “ecological civilization,” but it is clear that it is more than just environmental protection. The approach seeks harmony between the economy, politics, society and the natural world.

The constitutional tweak has also produced concrete results. Tan points to the cutting of subsidies for cotton grown on the North China Plain, an area stretching from Beijing to Nanjing that is famed for its fertile soil. One-quarter of China’s cotton crop is grown on the plain, and this has exacerbated the region’s water issues. Growing cotton requires over five times the amount of water per kilogram than cereals such as wheat.

Switching crops could save up to 8 billion cubic meters of water, double the annual consumption of Beijing. There is huge potential for savings across the economy, particularly in the inefficient agriculture sector, which accounts for 63% of water usage.

Nearly 50% of water used for irrigation, for example, is wasted. This is primarily because flood irrigation, the oldest and most commonly used method, simply dumps water on fields where most of it evaporates or runs off. The country has been investing in more modern methods, such as drip irrigation, which pipes water directly to plants, and to good effect. Irrigation efficiency rose from 0.44 in 2004 to 0.53 in 2016. This is still far below the developed world average of 0.7-0.8, but progress nevertheless.

But Parton is doubtful whether further efficiency leaps will be possible in the short term. “Low-hanging fruit can still be expensive fruit,” he says.

According to Parton, the dominance of smallholder farms may be a roadblock to investment. In 2013, 86% of Chinese farms were 1.6 acres or smaller. The government has been pushing corporate farming, but this has been inhibited by sluggish land rights reform. The efficiency problem is ultimately a political issue. “Until you can allow larger-scale farming, who is going to pay for these upgrades?” Parton asks.

Taxing Problems

Another potential solution is to use the tax system to discourage businesses and individuals from wasting water. Analysts have long observed that water is so cheap in China that overexploitation is almost inevitable. Until recently, water tariffs for businesses were $1 per cubic meter, a third of the rate in the United States, despite the US having more than triple the amount of renewable fresh water per capita.

Hebei Province has trialed a water resources tax, and a larger pilot project is underway involving nine further provinces. But raising the cost of water could risk the economy and social stability.

“Farmers, for example, are not used to paying for water,” says Parton. “Farmers do not make a great deal of money, and so if you start charging them a realistic price you will exacerbate their problems.”

The new tax avoids this by adopting a more granular approach. First, not all uses are taxed equally. Water for golf courses, for example, will be taxed at a higher rate than for non-luxury activities. Second, water extracted in areas experiencing high water stress is taxed at a higher rate than areas where water is plentiful.

These measures appear to be effective. Before the pilot, Hebei used only 13.8% of its quota of water from the transfer project. Since the scheme was introduced, 85% of water supply plants have changed their source from groundwater to transferred water, according to China Water Risk.

A separate pilot scheme is tackling water pollution—also an important contributor to water scarcity—by introducing a cap-and-trade system that requires factories to buy permits to discharge wastewater. In some areas, these permits now trade for hundreds of times their face value and can be used as collateral for loans. This encourages players unable to meet pollution standards to close up shop.

But such reforms may not be enough. Some of the most water-intensive industries, such as coal mining and power generation, will always be based in the northern provinces, where the resources are located. And most companies in these industries are state-owned enterprises with severe financial difficulties, which could ill-afford the extra costs of emission-saving technologies and higher charges.

Perhaps the most important lesson of the local trials, however, is that the water challenges are just that: local. China is often presented as a country of two halves, but in hydrological terms it is made up of over 1,100 separate catchments, or areas of natural water collection. If the issues are viewed at this micro level, problems that appeared imposing can suddenly seem manageable.

Dr. Wang Jiao, an associate at the World Resources Institute’s China Water Team, believes that there is reason for hope. Dr. Wang’s team has evaluated the effectiveness of a 2012 policy known as the “Three Red Lines,” which mandated stricter management of water resources by capping total annual water usage at 700 billion cubic meters by 2030, increasing irrigation efficiency and protecting water quality.

“We found that the rate of increase in water withdrawals slowed from 5.1 billion cubic meters per year in 2001-2010, to 1.6 billion cubic meters per year in 2010-2015,” says Dr. Wang. The team also observed that areas experiencing a decrease in water stress grew ninefold during those same periods studied.

Dr. Wang cautions that this does not mean that China is close to solving the problem, but it indicates that it is making progress. “We consider these results to be positive,” she adds. “At least it’s not getting worse.”

Man vs. Nature

If China is to reverse, rather than merely slow, water scarcity, there needs to be buy-in across society. Fortunately, this is starting to happen. Several sub-national governments are following Beijing’s lead in setting up their own water management systems, and these sometimes have even stricter policies. Regions are also slowly starting to work together to find solutions.

“Some provinces are working on river policy more collaboratively,” says Stephanie Jensen-Cormier, China Program Consultant for the NGO International Rivers. “They are looking at eco-compensation systems, which would provide compensation for areas that chose not to develop their section of a river.”

However, some observers feel that a truly sustainable solution must involve a fundamental shift in how China, and indeed humanity, views economic progress. Debra Tan, of China Water Risk, calls this “water-nomics.”

“We have to look beyond things like efficiency savings,” says Tan. “It is about wedding water resources management into economic planning.”

Doing this effectively in China would result in big changes in the global economy due to China’s leading position. According to Tan, one easily understandable change will be the disappearance of “fast fashion,” which relies on supply chains made possible in significant part by the abuse of water resources. “China’s manufacturing prowess led to the rise to fast fashion. So if China now changes the rules of the game, it follows that that business model will also change,” she says.

Readjusting the entire economy is a tall order, but far from impossible—China did it once already, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping. But the real curve ball is climate change. Nobody is sure how severe the effects will be, but research suggests that China will be hit hard.

One recent study by MIT found that that the North China Plain could become prone to severe heatwaves that top a “wet-bulb temperature” of 35 degrees (95 degrees Fahrenheit) by the end of the century. At that level of heat and humidity, even fit people sitting in the shade would die within six hours.

Such dire predictions have produced a growing chorus of fatalists arguing that climate change is a done deal and none of China’s efforts can prevent a crisis. But the only sure way to fail is to give up.

“It is about what is most important at the moment, and what is doable,” says Dr. Wang. “I believe if you do something, there is a high chance things will get better.”