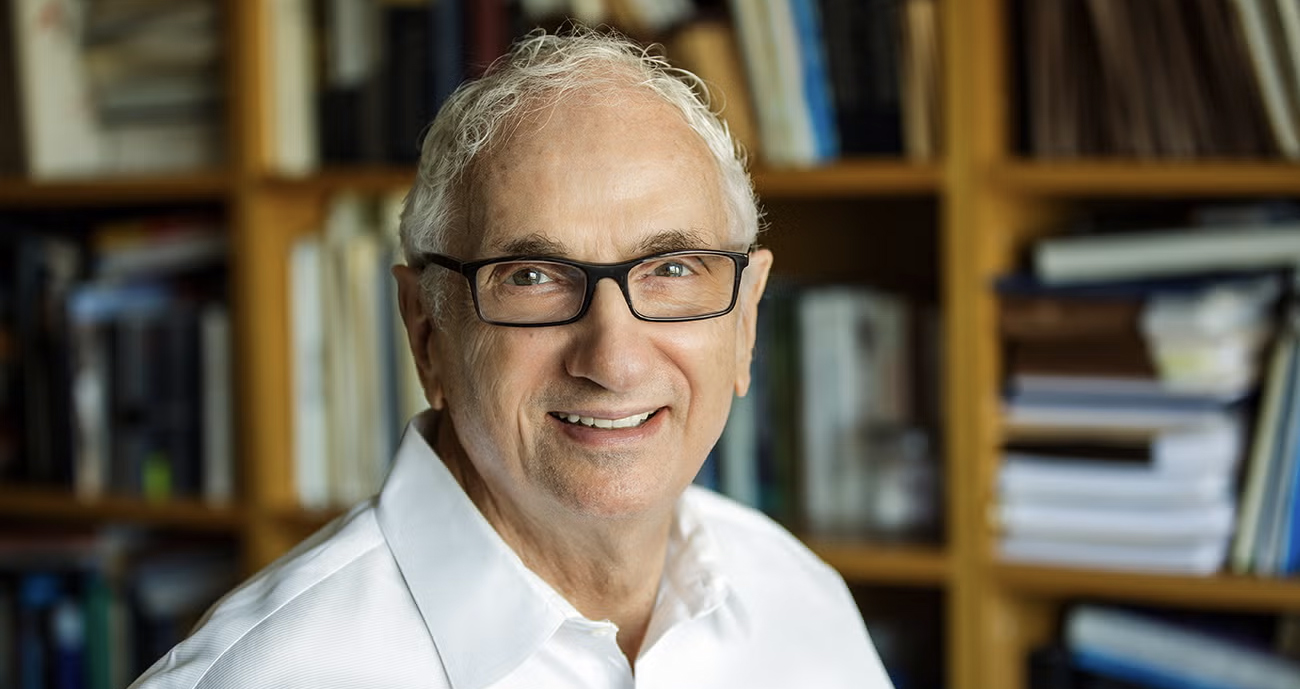

Shaun Rein, Managing Director of the China Market Research Group, talks about his new book, The War for China’s Wallet

One of the world’s most high-profile China experts, Shaun Rein made his name by highlighting new trends in the Chinese economy years before the Western media caught on.

In 2012, his first book, The End of Cheap China, highlighted that China’s low-cost manufacturing miracle was coming to an end. Two years later, he correctly predicted the rise of a new generation of innovation-led Chinese companies in The End of Copycat China.

Now, the founder of the China Market Research Group is back with his third book, The War for China’s Wallet. As he tells CKGSB Knowledge, the overarching message of this latest work is that it has never been more critical for brands to understand the Chinese market.

Q. What advice would you give to a business that is coming to the Chinese market for the first time?

A. What I would say is, understand the local consumer or local potential client. Really understand that your products and services might need to be localized. You want to keep your core brand DNA, but make it relevant for the Chinese consumer. Ralph Lauren is not relevant. When they have blonde-haired, blue-eyed models summering in the Hamptons—that’s not an image that Chinese can live up to. Have a nice lifestyle like Gucci, where the models have the same body shape as the Chinese, they tend to be a lot more petite.

Second, you’ve got to hire a China country head that lives in China, understands the China market and has a track record of success. It can be a mainlander or a foreigner, but it’s got to be someone who succeeded here. I mean, I had drinks last night with people from a huge company, where the CEO of China lives in Hong Kong. You can’t do that; you have to live in mainland China. To me, that’s like running your American operations from Puerto Rico.

Q. Are you surprised how many foreign brands come to China and do very little localization?

A. I talked to [British department store operator] Marks & Spencer and they said, ‘We’re Marks & Spencer, we cater to the suburban British housewife. That’s what we’re going to do here.’ I’m like, ‘There is no suburban housewife!’ And then the guy told me (this was the first or second year): ‘We can’t localize our sizes for Chinese. We have to bring the same clothes from the UK into China.’ It was ridiculous. They brought the same clothes, they didn’t even bring zeroes or twos or fours, it’s all size 16, 18, 20. It was shocking.

But, you know, I have to say: Asian countries make the same mistake. When I was at the Fifth Avenue store in New York for UNIQLO recently, they all had XS and S. You wonder, ‘Don’t they know Americans are like dinosaurs compared to Japanese?’ You need to get bigger clothes. So, it works both ways. Shocking.

Q. One of the key arguments in your book, The War for China’s Wallet, is that Chinese consumers can be mobilized to reward or punish brands based on a country’s relationship with China. The most striking example recently has been South Korea. How worried should brands be about this trend?

A. Brands need to be very worried. They need to understand the geo-political situation better now than at any time before. Five, ten years ago, you basically had to understand: what did the Chinese consumer want, what types of products or services, what’s the right marketing communications strategy? But now, it’s very clear that China is using its economic wallet and its muscle to reward and punish other countries—and, increasingly, companies—to ensure that they adhere to its political wants.

Q. What practical measures can brands take to protect themselves from this?

A. It’s not easy, frankly. I think there are a couple of things. They can, first and foremost, show from the very beginning that they’re friends of China. In the book, I used the example of Yum! Brands—KFC. They have always shown the everyday Chinese people that they respect the culture, respect the people. And they have done it by creating egg-and-milk food programs for poor schoolchildren throughout the country. That’s really important, because when there was South China Sea tension a year ago, sales in some parts of China for KFC dropped dramatically. But they rebounded after a month or two, because at the end of the day, the consumer realized KFC is a friend of China, and that’s a really important thing.

Secondly, you probably need to join associations. No single company can push back against the Chinese government, so you need to form blocks of 20, 100, 200 companies. Then, if one of them gets attacked, they can unify together and say: ‘Hey, wait a minute. This is not this company’s problem, this might be a government issue, don’t punish us.’

Q. How can brands from countries that generally enjoy a positive image among Chinese consumers take advantage of this without making themselves vulnerable?

A. It’s tough. I think iconic brands that represent a country are dangerous. It’s better to be affiliated, but not too representative. For example, Costa Coffee customers don’t always know it’s British. Right now, Harrods is doing fabulously well, because for Chinese, when they go [to London], it’s a destination. If you go to the UK, you have to shop at Harrods. The risk though, for Harrods especially, is that if there ever is tension between China and the UK, Harrods will be the first thing to get hit. Costa Coffee won’t be. It’s Toyota, it’s KFC, it’s Starbucks, it’s Apple… It’s good to show you’re from a certain country, but it’s also not good to emphasize it too much.

Q. Is there a chance this approach will become less effective if used too often?

A. That’s a great question. I think Chinese consumers don’t view it as propaganda, but rather as pride in the country. I think it’s a strategy that they can employ over the next 10-20 years, and it’s not going to make a difference. Even when we interview Chinese who were educated abroad and they come back, they still get really worked up.

The bigger risk is: will China go too far and cause too much worry for other governments, to the extent that that they do band together and they push back? Maybe they don’t band together in ASEAN, but maybe they band together in TPP. There are all these new organizations that are popping up. China needs to worry about that, that they don’t oversell their economic power.

Q. What role should governments play in terms of helping their own domestic brands position themselves in China?

A. I’m not sure they need to help position brands. What they need to do is help lobby governments more. I agree with Trump for pushing for more market access for financial services firms, and for beef. You need to take a respectful but strong line with China. And that’s why I liked Trump’s meetings here [in November]. He said (not a direct quote): ‘You’ve taken advantage of us, business-wise, but I don’t blame you.’ I think that’s a good way of doing it, because it’s saying, ‘You’re smart; you’re not evil. I’m not demeaning you, but now it’s got to stop. We now need to have a more equitable playing field.’

I think that’s what national governments need to do when it comes to technology, when it comes to financial services, because protectionism in China isn’t increasing—it’s always been there. It needs to stop. There are a lot of barriers that the government has put in place for foreign companies that might have made sense 20 years ago, when the country was just developing and needed “infant protection,” but now I think that the competition would only help China.

Q. Chinese outbound investment boomed in 2016, but then the government pulled it back in 2017. What do you expect for 2018?

A. I think that crackdown is a slight blip. I expect the outbound M&A will not grow as fast, but it will grow slowly but steadily over the next three to five years. I think the government wanted to stop companies where there wasn’t a lot of transparency. Were these companies just trying to get money offshore and untaxable? Were they trying to convert and do capital outflow in order to evade capital controls? Were they causing a systemic threat? If it’s the state-owned banks that are lending them all the money, if these things blow up, then what happens to the banking system? And that’s why the government is saying, ‘You can’t borrow money from state-owned banks or private Chinese banks; you can go to the HSBCs and Citigroups of this world and use their compliance and credit-risk officers.’ And if they blow up, it hits the UK; it doesn’t hit Bank of China.

Q. Will there also be a shift in the focus of outbound investment?

A. It’s going to be more Belt and Road-oriented, it’s going to be more technology-oriented. It’s more about bringing brands back into China, bringing technology back into China. Belt and Road especially—I think people are underestimating the potential for that. I think a lot Western journalists are poo-pooing it and saying, ‘Oh, this isn’t going to work, these are previously announced ventures.’ It doesn’t matter, because it’s now a systematic, methodical initiative that can rally all of these different nations, all of these different governments to China’s side. I think it’s brilliant. The question is, can they do it? But, even if they don’t do it as well as they hope, it’s still going to help them. But there are a lot of minefields, like between Qatar and Saudi Arabia. How do you support and take sides when you’re trying to be partners with both? That’s a fundamental issue: I think China can’t always run everything by saying they’re not going to get involved.

Q. How worried should Chinese companies be about the European Union and US strengthening oversight of Chinese investment?

A. It’s definitely a concern, and this comes down to the blocks that I was talking about—the [Chinese] government might overstep by punishing. You know, there’s a feeling that they can punish the Asians or the Africans and get away with it. Will the Europeans allow it? Probably not, because I think there’s a little bit more truculence, belligerence.

Q. As you describe in the book, many potential merger-and-acquisition deals go awry because of a culture clash between Chinese companies and their global counterparts. What are the main features of this clash?

A. I think there are a couple differences: Chinese companies, private ones, still tend to be controlled by the founder, entrepreneur, chairman. And he makes decisions quickly, he makes them himself and doesn’t delegate. So, it’s one man at the top: this is very different from American or British companies that have been around for 100-200 years and have layers of middle management. What you hear time after time from Western companies is that the Chinese aren’t trying to create long-term relationships—they want to maximize their profits this year, and they don’t care if you don’t like them because they don’t expect to do business with you ever again. But the reality you have to learn is that you probably will do business together again, so there has to be a little bit more gentlemanly civility when doing business.

Q. How much of that culture clash is a result of the economic conditions in China right now?

A. For sure, it’s about China’s conditions right now. Think short-term for profit, because you never know if the opportunity is going to be there in the future. And I find the Chinese don’t care about other people; they care about people within their own guanxi (personal network) circle. Everything else is a war. So, if you’re trying to negotiate with a shopkeeper on the street, they’ll try to extract every last penny from you. But once you become a friend with them and you’re in that guanxi circle, they’re the best people of all time.

Q. Do you expect China’s big companies to start resembling global companies more in the future?

A. Yes, much more. You’re already starting to see that as companies like Tencent hire foreigners and Chinese who have worked in foreign companies. It’s not an easy process, it’s not like you can work in a foreign company for three years and bring it back. We’re talking decades. It’s going to be a generational thing. And you’ll understand that the world’s not a zero-sum game. I’m a firm believer that everybody can make money together, you’ve got to share the pot.

Q. If a company in Europe or America is approached by a Chinese investor, what issues do they need to consider?

A. They need to know how legitimate it is—don’t open your kimono too wide. You can tell them you’re interested, but you don’t want to share too much detail, because, frankly, they might just be trying to steal information from you. We’ve had big companies call us and say, ‘Shaun, we want you to do our strategy for us, so we want you day-by-day to write a plan for six months, of what we should do.’ I’m like, ‘Wait a minute, that’s the proposal? You’re just going to take it and run the marketing campaign! You need to hire us first.’

Second, don’t salivate that you’ve got a big money guy coming in—it’s better to try to go slowly. If you’re a good business, the Chinese will still come.

Third, understand the culture. That’s a big one. Don’t be overly scared, actually, with speed. Sometimes, they do move truly fast, and it’s not necessarily because they have bad intentions. You should be more fearful of the Japanese. Because the Japanese, in the 1980s, when they made acquisitions, they fired the top layers and they put in bamboo ceilings for non-Japanese managers. The Chinese, very often, will put the money in and say: ‘You’re foreign and I respect you. You’ve got good management, teach us!’

Q. Foreign direct investment in China, particularly from Europe, has stalled in the past year. Why do you think this is?

A. You know, China’s a great market, but there are a lot of other markets now. Ten years ago, if you wanted to sell to a billion consumers, where would you go? You could only go to China. Now, India is coming up, Indonesia is very strong, Malaysia, Thailand and Africa… so it’s not the only game in town. I would recommend that the Chinese government tries to be seen as more pro-foreign investment. Right now, they’re not. With the new visa situation—it seems like they don’t want foreigners.

It’s also that the economy is weak. I think it’s weaker than people realize. I’ve always been one of the biggest bulls [on China]. I’m now not one of the big bulls. I would be investing in Vietnam right now. That’s the place to be. Southeast Asia is where the really fast growth is going to be over the next five-ten years.