According to the World Bank, China is set to become the largest economy in the world by the end of 2014. But China’s rise to economic superpower status comes at a cost to its international maneuvers.

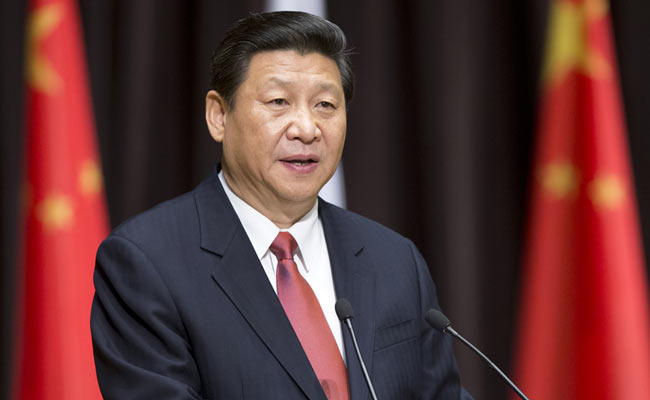

China’s economy has emerged rapidly in the past two or three decades. It surpassed Germany’s in 2009 and Japan’s in 2010 and is slated to become the world’s largest economy this year, according to a World Bank report. China has therefore attracted the world’s attention on a variety of fronts—political, economic and strategic. The world watched nervously in May as a collision between Chinese and Vietnamese vessels in the South China Sea threatened a serious escalation of tensions in the Asia-Pacific region. As Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive intensified, international media pondered the implications for foreign corporations whose Chinese partners were on the receiving end of the crackdown, from Canada’s National Petroleum Corp to the British cereal maker Weetabix. The rise of Alibaba from a Chinese startup to the world’s largest e-commerce company is about to make history, according to some, on the New York Stock Exchange with a record-breaking IPO value.

With greater power, however, comes greater scrutiny. As China becomes stronger it will use its soft power to play an increasingly important role in global politics. Small nations in particular will be attracted by the many benefits inherent in cooperation with the world’s largest economy, but so will developed nations. But scrutiny from developed nations will also increase, a prominent example of this being the United States’ foreign policy pivot to Asia and efforts to develop the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Economic power will necessarily lead to increased military power and strategic influence as well—so-called superpower status. Yet China is very different from the US, which has been the world’s only superpower since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The rest of the world has grown accustomed to its superpower status. China, on the other hand, is a new superpower both economically and politically. It is this element of the unknown that has created a certain amount of international anxiety. Other nations don’t know what to expect as China steps into its position as a new world leader.

This should come as no surprise to students of history. Whenever a new superpower steps onto the world stage, it naturally tends to cause discomfort on the part of the old superpower, which is typically reluctant to renounce its influence. Due to such fears, for example, the United States plans to strengthen cooperation with Japan to counterbalance the rise of China in the Asia-Pacific region.

A major benefit of China’s emerging superpower status is the ability to reduce its economic dependence on other nations. The world is dangerously reliant on the World Bank and other financial institutions, where the United States wields an inordinate amount of influence. A major issue currently is the inequitable distribution of shares. In the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the United States controls nearly 18% of Special Drawing Rights while China, rapidly becoming the world’s largest economy, controls a mere 4%.

To counter this, China recently signed a deal with Russia, India and the other BRICS nations to create a New Development Bank and is currently in talks with Korea to set up an Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Such institutions would counterbalance the financial domination of the World Bank and the IMF. That China is able to credibly propose such plans is directly related to its growing economic clout. Therefore China’s emerging economic power represents an encouraging development for emerging market nations.

As another example, the international financial system is dominated by the US dollar. This international demand for the dollar has resulted in a situation where quantitative easing (QE) and other domestic policies of the US Federal Reserve often exert a dangerous destabilizing influence on markets worldwide. When the Fed announced plans to begin tapering QE in late 2012, emerging market nations experienced sizeable stock market drops as well as increases in sovereign spread, a measure of the risk involved in lending to a given country. An important solution to this dependency is the internationalization of the renminbi. Reducing dependence on the dollar, the euro and other foreign currencies is China’s ultimate goal, and its new title as the world’s number one economy could help China reach this goal by giving it added leverage in negotiations.

Of course, even if China becomes the world’s largest economy, this does not mean domestic affairs will be easy. In fact, China’s new status will escalate citizens’ expectations for material wealth and continuous economic growth, making domestic politics increasingly complicated. China will be forced to work harder to improve social welfare and reduce debt, while its newfound superpower status also gives it the added burden of projecting its soft power worldwide.

What’s more, Chinese society is in a state of transformation. It is, in a sense, unprepared to fill the role of an economic and political leader. China will need to work to emerge as an economic leader independent of the aegis of the US. It can begin to realize this goal by taking actions that illustrate economic leadership, such as providing foreign aid to developing countries and helping to determine the course of the global financial system, to cite a few examples.

China will also have to work hard to win the respect of its neighbors as well as Europe and North America. It must develop its economy while increasing transparency, projecting its image as a responsible and reliable world citizen. This will help China’s case in the South China Sea dispute and in other issues of international relations. It is also important to present an image of nonaggression even as it consolidates its economic power.

There is space within China’s current political system for China to become a responsible global leader, but it will not be easy. Even as the Communist Party retains its hold on power, China is changing and democratizing. This has been underscored most recently by Xi Jinping’s fight against corruption.

Though China is a Communist country, nations of all ideological stripes are able to engage in peaceful and constructive diplomatic and economic relations with China today. This will surely be a boon as China steps into its new role as a world economic power.

Zhou Chunsheng is Professor of Finance at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business.