Many companies are now pursuing a ‘China plus one’ strategy to lessen their reliance on the Chinese supply chain

A standing ovation when China’s president takes to the stage is nothing unusual. Still, it was not an ordinary audience that applauded Xi Jinping in San Francisco one rainy night last November. Crowding into a hotel ballroom were more than 300 US political and business elites—including Elon Musk of Tesla, Apple’s Tim Cook, and Pfizer head Albert Bourla—all seeking a chance to talk with the Chinese leader.

Xi, on his first visit to the US in six years, sought to soothe the nerves of the corporate chieftains—many of whom had a vested interest in maintaining good ties with China. “We are in an era of challenges and changes. It is also an era of hope. The world needs China and the US to work together for a better future. China is ready to be a partner and friend of the US,” Xi said.

The speech went down well but US-China relations remain at best cool, amid renewed talk of decoupling and now de-risking. There is recognition on both sides that full-blown decoupling—that is, the complete bifurcation of the world’s top two economies—would be almost impossible, not to mention disastrous.

“Companies are not going to leave China, you can’t not be in China,” says James McGregor, Greater China chairman at APCO Worldwide. “The equation has always been, this is a problematic and difficult market, but it’s still the market where the largest middle class will emerge in the next couple of decades.”

De-risking—the process of reducing exposure to the Chinese market—has now superseded decoupling, but the softer language belies the negative impact that the trend has had on China in recent years.

A word of difference

As the US and China began mutually escalating tariffs on their massive trade flows in 2018-2019, the chatter of decoupling began to surface in Washington. “Decoupling was introduced mainly during Donald Trump’s administration and had a tone of absolute finality to it—that you were somehow looking to completely separate the two economies,” says Ken Jarrett, a senior advisor at Albright Stonebridge Group and former president of AmCham Shanghai. “That would be quite intimidating to most companies, as well as most fair-minded Americans or Chinese.”

There is a question of who started the decoupling process, and many analysts, such as Steven Okun, CEO of APAC Advisors and senior advisor at McLarty Associates, see the Made in 2025 policy—a Beijing-led industrial policy unveiled in 2015 that aimed at ending China’s reliance on foreign technology imports—as one of the triggers.

“For many years China has been looking to improve its indigenous capabilities in strategic sectors like semiconductors and telecommunications, in part because it realized it was too dependent on foreign technologies,” says Alfredo Montufar-Helu, head of the China Center at a global think tank, The Conference Board. “That is a vulnerability that can be exploited by other governments—as is happening right now—so China’s focus on building technological self-reliance via policies and initiatives like Made in China 2025 and, more recently, the development of so-called ‘new quality productive forces’ is not at all surprising. It is a matter of national security for the Chinese government.”

From the outside perspective, there has also been a growing desire to reduce dependency on China’s manufacturing capability and supply chains. The de-risking strategy caught on after European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen coined the term a year ago ahead of a spring visit to Beijing.

De-risking quickly gained currency with US officials, and less than a month after von der Leyen’s remarks, US national security adviser Jake Sullivan referenced her when he said Washington “converged with key European leaders in saying we are for de-risking, not for decoupling.”

“A company sourcing all its inputs from a single supplier, or even a single country, would be de-risking when it acts to diversify its supply chain. Decoupling would be eliminating any activity from a single company or supplier,” says Okun. “From the perspective of foreign businesses, the shift in language when discussing the reduction of economic interdependence on China to include both decoupling and de-risking is more accurate.”

But the line between the two approaches is somewhat blurred, and China has complained that de-risking is in fact decoupling in disguise. The country has, however, had something of its own de-risking campaign in place, involving a state-led push to develop domestic technologies and materials, thereby curbing imports for critical supply chain segments.

“When the US and Europe do it, it’s called decoupling and de-risking. When China does it, they call it self-reliance,” says McGregor.

Fork in the road

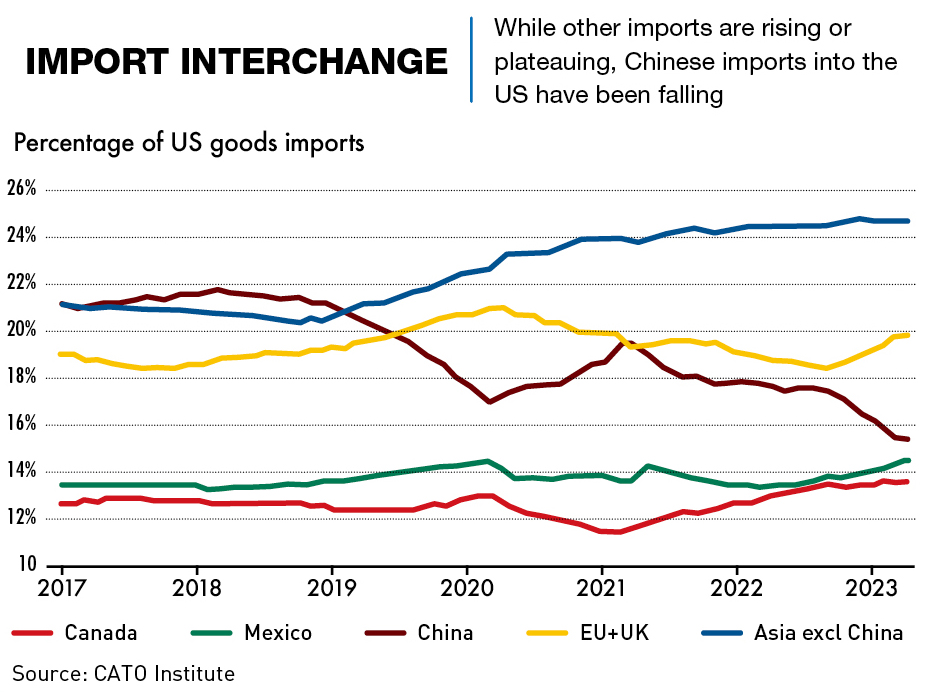

There is evidence of some distancing between the US and Chinese economies in recent years. The US trade deficit with China fell last year to its lowest since 2010, plunging by more than $100 billion to $279.4 billion, according to the US Bureau of Economic Analysis. Mexico also last year replaced China as the US’s main source of imports.

The apparent parting of the ways between China and the West has been most pronounced in the finance and high technology sectors. China’s net foreign direct investment (FDI) fell to $42.7 billion last year, down by nearly 80% from 2022 and the lowest since the country joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.

Increasingly vigorous oversight of consulting and due diligence companies, and curbs on international access to various corporate and economic databases have particularly undermined the investment case for China and prompted some foreign firms to think twice about committing more resources to the world’s second-largest economy.

Beijing also continues to maintain tight currency controls which make it difficult to move funds in and out of the country. The issue spilled out into the open briefly last year when billionaire investor Mark Mobius publicly blamed the controls for preventing him from withdrawing money out of China.

Currency restrictions, and the more complex geopolitical landscape, have also reduced Chinese outbound FDI to Western countries. Chinese flows to the US in particular have collapsed, from $46 billion in 2016 to less than $5 billion in 2022.

Foreign business lobbies in China, such as AmCham and its European counterpart, have long complained about the regulations covering cross-border data transfers. A new version of the rules released in March relaxed some of the requirements, but retained an expansive interpretation of sensitive personal information that could increase the administrative burden for companies sharing data overseas.

The US strategy of restricting key technologies from China has hit the Chinese microchip industry especially hard. In response, China has mobilized tens of billions of dollars under several ‘Big Funds’ that aim to propel semiconductor self-reliance, but it is unclear if the massive investment will pay off. “Supply chains for semiconductors are so vast and touch so many countries that it’s going to be very difficult, if not impossible, for any country in the world to be able to be completely self-reliant on microchips,” says Montufar-Helu.

Washington’s watchful eye is now also extending into biotechnology. “The sector has been lurking on the sidelines for a while and now it’s definitely in the limelight,” says Jarrett. “BGI and WuXi AppTec are current targets of that effort in the US.”

Foreign business lobbies have also long complained that China’s controls on the internet limit business competitiveness.

Brussels shouts

The US is not alone in seeking to recalibrate its economic relationship with China. The EU’s position took a distinct turn in 2019 when it called Beijing “a partner for cooperation, an economic competitor and a systemic rival”—a shift in messaging that aligned Europe closer to the US. A landmark EU-China trade and investment pact announced in 2020 then failed to pass the European Parliament, as tensions rose sharply after China responded to EU sanctions with sanctions of its own.

More recently, EU-China ties have been further strained by the deepening alliance between China and Russia following the invasion of Ukraine, and surging exports of Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) to Europe that could threaten the continent’s automotive industrial base.

China has sought to offset the growing discord by boosting economic engagement with the Global South. Beijing feted world leaders from developing countries last October when it hosted a forum to celebrate a decade of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which still enjoys strong support in many areas of the Global South. Non-financial FDI from China to BRI partner countries surged by 22.6% year-on-year in 2023, twice as fast as the overall growth of 11.4%

Turning a new leaf

Keenly aware of discontent among many foreign business people, the Chinese government has launched a charm offensive. Shortly after China’s annual legislative meeting the State Council released an action plan listing 24 measures aimed at boosting foreign investment, including easier procedures for visas and residence permits.

There has also been a recent flurry of engagement at the highest levels of the American and Chinese governments. US National Security Adviser Sullivan met Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi in Bangkok in January, while Xi followed up his meeting with US President Joe Biden in San Francisco last November with their first phone call since July 2022. In April, Treasury Secretary Yellen visited Guangzhou, where she voiced rising concerns about China’s industrial overcapacity.

Beijing has also stepped up efforts to rebuild bruised relations with Europe. It took the surprise step of offering visa-free travel for six European countries last December, and expanded the measure to further nations in March.

The outreach has also taken the form of more high-level face-to-face diplomacy—Wang Yi toured Germany, Spain, and France in February in an effort to thaw relations, while commerce minister Wang Wentao visited Paris in April to argue Beijing’s case over European scrutiny of Chinese EV industry practices. This all laid the groundwork for a trip to Europe by Xi in May. Momentum appears to be building as a result. The number of new foreign-invested firms set up across China in January-February grew by 34.9% year-on-year.

Defanging de-risking

While it works to assuage foreign concerns, Beijing is also attempting to mitigate the impact of de-risking by emphasizing “new productive forces,” a term that refers to future-facing disruptive technologies. Take the arms race over semiconductors for instance—despite US sanctions, the Chinese industry still appears to be making strides in advanced chips, with Huawei last year unveiling an unexpectedly advanced, self-designed 7-nanometer (nm) chip to power a flagship smartphone.

Further progress is expected, but this will be slow, and there is no guarantee China will ever catch up to US leadership at the cutting edge of microchips.

Chinese businesses in the private economy have also adopted a de-risking mindset as they look to sidestep the commercial impact of geopolitical tensions. Mexico, seen as a backdoor for the US market, has seen investment from China surge in recent years—by IMF estimates, mainland Chinese FDI in Mexico grew from $744 million in 2018 to $1.19 billion in 2022

The increase can be attributed to Chinese companies “nearshoring” operations in Mexico to bypass US tariffs on Chinese imports. Proximity also makes Mexico a tantalizing possibility for firms targeting the US market because companies do not need to wait weeks for goods to be shipped from China. Morocco, by dint of free trade agreements, appears to be serving as a similar Chinese conduit to European and American markets, as several Chinese battery metal players have announced investments in the North African country.

Chinese firms are going to great lengths to deflect anti-China sentiment from the US and other countries concerned by Beijing’s policies. Some—such as SHEIN, the world’s biggest fashion retailer, and Pinduoduo, the world’s second-largest e-commerce platform—have relocated their headquarters outside China, perhaps in an effort to play down their Chinese origins.

Though the challenges are rising, business surveys indicate exiting China completely is unfeasible for most foreign businesses. Rather than reduce their China presence, many companies are focusing on insulating their China operations from rising tensions. Some, such as Apple, are making progress in creating alternate production bases outside of China, while others, such as ExxonMobil, VW and BlackRock are opting to silo their China operations, walling them off from the global business so that they can withstand disruption from potential scrutiny or sanctions.

Jarrett also points to a trend of foreign companies trying to look more local. “It could mean localizing your executive team, a transition that has been underway in American companies for quite some time already,” he says. “More companies are thinking about joint ventures (JV), even though for many years nobody wanted to enter into a JV. Now there’s a recognition that a JV might give some welcome protection.”

Many foreign companies are also pursuing a “China plus one” strategy, moving some production out of China, even though the approach comes with extra costs. “China plus one still has to pass the business case, it’s not free,” says McGregor.

De-Day

While many corporate executives and officials resist the notion of decoupling, there is little doubt that efforts to reduce economic exposure to the Asian powerhouse are gathering pace. Intensifying scrutiny from the US and EU indicates decoupling and de-risking are unlikely to fade, especially as China looks to future-facing technologies to revive growth.

“What we’ve seen out of Washington in the last few months is a taste of things to come,” says Jarrett. “At first the focus was on semiconductors and artificial intelligence. Now we’ve moved onto made-in-China cranes in US ports, Chinese EVs, biotechnology, and TikTok. More and more issues are getting folded into the national security category. People will start to anticipate what else could be next because you don’t want to make a long-term investment in an area that in a year or two is now on a blacklist.”

Even as multinationals look to spread their exposure more evenly around the globe, they can play a positive role in encouraging dialogue between China and an increasingly wary West. Business has always been common ground between the two, and could yet be what keeps tensions from spiraling further.

“The US and China look at each other as strategic competitors. I worry about it slipping into strategic adversaries,” says McGregor. “That’s why the business bridge is extremely important, it’s the ballast in the relationship between countries. We have to figure out how to keep that business bridge going.”