Ups and Downs

Convincing consumers to part with their cash can be a difficult prospect and there is a need for demand-side stimulus in China

As she picks out groceries at her local supermarket, Chen Jinwen now checks prices more than she has ever before. “I’ve always been quite conscious of my money and have the habit of tracking my expenses in an app on my phone,” says the IT project manager who lives in the eastern Chinese city of Nanjing. “I feel like I need to be more careful with my spending, both because prices went up but also just in case my situation changes in the future.”

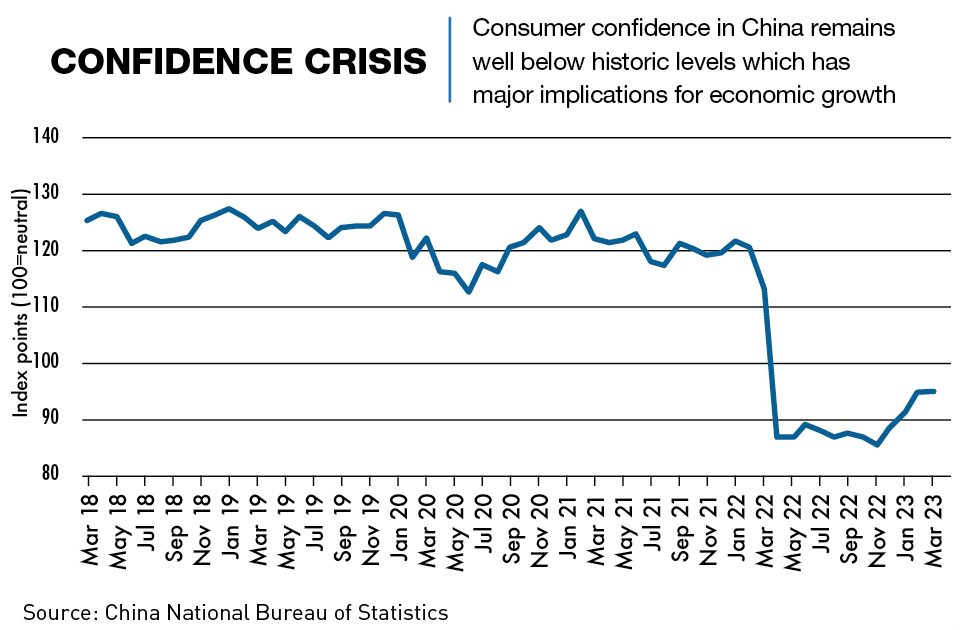

Chen is one of a growing number of Chinese consumers who have become hyperaware of how much the cost of living has risen in China, with many adopting more conservative attitudes toward spending and thinking twice before making purchases. Inflation is a factor in this thinking, but the underlying issue for Chen, and millions of others, is confidence in the stability of the economy.

Economic headwinds, the lasting effects of the volatility of the COVID-19 years and growing uncertainty about the future have resulted in an increased reluctance to spend. What is worse is that the Chinese government’s growth plans heavily rely on rising consumer spending to make the slowing cogs in the economic machine turn faster.

Many are trying to get a handle on how consumer spending is trending, with estimates in the first few months of 2023 varying and opinions ranging from “Consumers are being cautious” to “Consumer spending is in a strong rebound.” But what is clear is that without robust spending, overall long-term economic growth will be impacted.

“Declining consumer confidence could have its origins in long-term structural headwinds. Slowing demographics and rising debt levels may have ebbed on households’ propensity to consume because they felt less certain about the future due to these factors,” says Carlos Casanova, Senior Economist for Asia at the wealth management firm Union Bancaire Privée. “If consumer spending remains low, if for example, China is unable to effectively pivot its economic growth model, then we would expect to see a decline in potential overall growth.”

Royal flush

Over the past two decades, China has undergone a transition into an increasingly sophisticated consumer economy. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, over half of the country’s 1.4 billion people are now categorized as middle class, up from just 3% in 2000, and disposable income per capita increased by around 700% over the same period—the global average increase was 200%.

As well as the increased availability of cash to spend, greater access to credit and other financial services have also helped drive consumption in the country across a number of different categories. Entertainment and leisure, food and beverage, education, health, renting, transport and apparel make up the large majority of spending, and according to figures by China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the bulk of Chinese household consumption in 2022 was on food (30.5%), housing (24.0%) and transport (16%).

As incomes have risen, Chinese households have also increasingly begun to spend on luxury items and services that they previously could not afford, including high-end electronics, imported cars, luxury vacations and premium education and healthcare services. As a result, China became the world’s second-largest luxury consumer market in 2008 and by some measures is now the largest.

“With the Chinese economy lifting as a whole, consumer spending went through a ‘consumption upgrade’ where people start buying higher quality products for less,” says Allison Malmsten, a B2C marketing expert at Daxue Consulting.

Interestingly, thanks to the country’s fast economic growth, while Chinese consumers’ overall spending has increased over the last two decades, the country has also consistently managed to maintain one of the highest savings rates in the world, in part thanks to the prudent financial management endemic in the country’s culture. Gross national savings as a percentage of GDP reached 44% in 2021, significantly higher than savings rates observed in the United States (17%) and Japan (26%).

“Chinese consumers are more likely to save additional income rather than spend it compared to their global counterparts, especially amongst developed markets,” says Casanova. “This ratio has declined gradually since its peak in 2010 (51.6%), reflecting a steady increase in Chinese households’ marginal propensity to consume. However, this remains low compared to the United States.”

At the same time, the country’s private sector is also feeling the strain from a lack of consumer confidence, with the CKGSB Business Conditions Index (BCI), a measure of business confidence, showing a correlation with consumer confidence levels. The BCI however, while showing a similar trend, has managed to return to above the 50 point confidence mark, while the national tracker for consumer confidence remained at 94.9—below the 100 point neutral mark—in March 2023.

The long-term trend of slowing economic growth in the country has exacerbated the existing propensity for financial caution and made it more difficult for the government to kick-start spending.

Pinching pennies

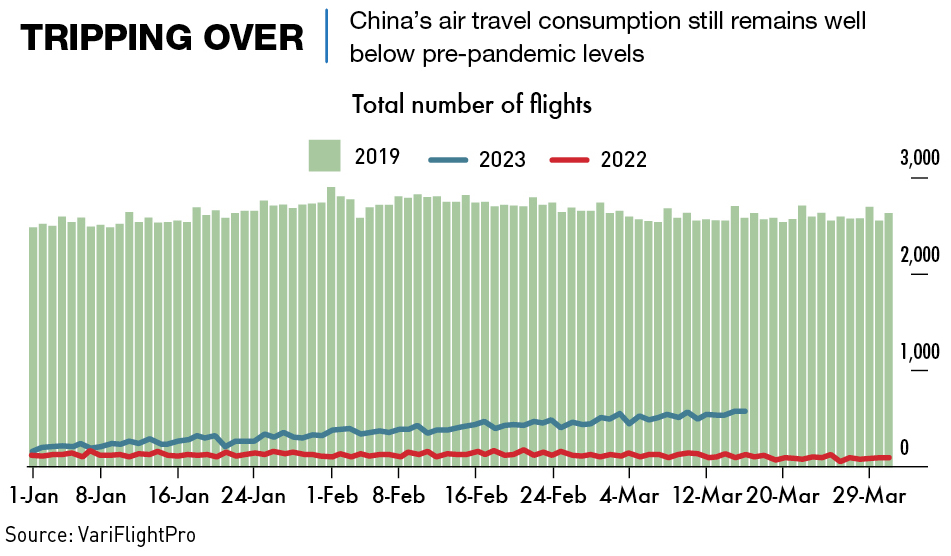

Although consumer spending was on the rise over the past two decades, the COVID-19 pandemic had a notable negative impact. Following the outbreak, China saw a 32% decline, or ¥329.8 billion ($45.92 billion) drop, in offline consumption in 214 cities across the country. Despite an initial surge in spending after pandemic-related restrictions were lifted, Chinese consumers’ willingness to shop has yet to rebound to pre-pandemic levels, and 2022 was one of the slowest years for economic growth in decades.

In the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, there was widespread panic-buying and hoarding of essential goods, such as food and medical supplies. This led to shortages and price spikes, which eroded consumer confidence.

“There were several waves of panic buying between 2020 and 2022,” says Chen. “It was first masks, then groceries, and the last being COVID-19 home testing kits and flu medication. I remember there also being cases of stores hiking up their prices, even though the government had prohibited them from doing so. I felt really worried about getting ahold of basic necessities at the time.”

Confidence has been dented by various other factors, including trade tensions with the United States, a slowing economy, and growing unemployment. Consumers are more interested in saving and investing their money than ever before. According to McKinsey’s 2023 nationwide survey of Chinese consumers, 58% of urban households indicated their desire to “put money away for a rainy day,” the highest level since 2014, and 9% higher than in 2019.

More reserved attitudes towards spending in recent years have, for example, led to South Korea overtaking China in terms of per capita luxury spending. In 2022, Koreans purchased $16.8 billion worth of luxury brand merchandise, equating to $325 per capita, compared to $50 in China. The China market remains larger in total due to its massive population.

“Chinese consumer spending has declined overall and you can see this in how luxury sales have dropped, how property sales have taken a hit, and how there are more and more stores selling second-hand products,” says Joyce Ling, Chief of Transformation and Strategy Officer for Greater China at global marketing communications agency Wunderman Thompson. “I don’t believe that spending power has changed to a great degree, but it’s more about how consumers are choosing to spend their money that has changed.”

China’s labor market remains under pressure with high levels of unemployment, which also contributes toward an unwillingness to spend. The surveyed unemployment rate was above target in 2022, reaching 5.6% on average compared to 5.1% in 2019. More importantly, youth unemployment reached 20.4% in May 2023, almost double the pre-pandemic levels of 11.9%.

“A lot of Chinese people who were working abroad, such as in Silicon Valley, have been laid off and they’re coming back to China to look for jobs,” says Ling. “Students who would have studied abroad and perhaps started working abroad are still in China. This is exacerbating the already competitive job market.”

“Another factor here is regulation,” says Casanova. “This impacted predominantly the housing sector and platform companies. However, given that both sectors play a sizeable role in the economy, this could have had an impact via wealth effects.”

In China, the balance of assets is much more heavily weighted towards state and corporate holdings than households, compared to Western and developed economies. Data from the International Monetary Fund shows that as of 2020, households in China held about 57% of financial assets, while corporations held about 43%. The situation in China stands in sharp contrast to countries like the United States where households account for around 71% of all assets. Other countries like Japan and Germany also have significantly higher amounts of household financial wealth in comparison to China.

The new normal?

Now that China’s zero-COVID policy has been lifted and borders are open again, consumption is expected to rebound to pre-pandemic levels eventually, but how long it will take to get there and when it will grow to become the economic driver that Beijing requires is yet to be seen.

Even with government officials and businesses hoping to see a greater rebound in the second half of 2023, experts predict that it could take significantly longer than that. “Consumption is going to bounce back a lot faster in Tier-1 cities,” says Ling. “We’re going to see a quick peak in consumption now because everyone is finally free to go out, travel and shop. But it’s likely to drop and steady out after that. That steady point is going to be lower than pre-pandemic levels and it’s going to take a few years before China can see the consumption levels that existed before COVID-19.”

“The pandemic caused many businesses to close their doors for good,” says Wei Li, a restauranteur in Shanghai. “Things remained very uncertain for years, and we had to let most of our staff go. When the zero-COVID policy was lifted, our restaurant was quite busy every day, but this level of business would have to be sustained for a long time to make up for all that we had lost during the COVID years.”

The sudden decline in consumer spending due to COVID has had a ripple effect on many sectors of China’s economy. As private consumption has accounted for 40% of GDP in recent years—compared to close to 70% in the US—this decline has made a significant contribution to the economic slowdown.

“China’s future growth rate must lag the consumption growth rate, and so its overall growth depends crucially on the growth rate of consumption,” says Michael Pettis, a professor of finance at Guanghua School of Management at Peking University in Beijing. “There is simply no way China can continue to maintain investment rates above 40% of GDP much longer.”

The slow rebound is also having a severe impact on the many companies that flocked to China as it became the world’s biggest consumer market. During the pandemic, consumers began focusing their spending on things that had a practical value in their lives, resulting in a surge of more wellness-oriented purchases, such as yoga gear, meditation workshops and cookware. Many businesses are already re-evaluating their approach and aiming to connect with consumers not just on a transactional level, while also aiming to show customers the value that their products could provide, in the hopes of stimulating faster recovery.

One example is IKEA’s partnership with SONOS to create mood-boosting speaker lamps. Lululemon, which sells athletic apparel and only entered China 10 years ago, saw business really take off in China during the pandemic, thanks to the growing emphasis being placed on health and wellbeing by the country’s middle class.

“Before 2022, a lot of Western companies were betting on China because things were not happening in the West,” says Ling. “There are a lot of changes in foreign trade and domestic demand, so they’re a little uncertain right now. Some of our clients in the beauty and consumer goods business are changing the way they look at marketing and investment. They’re not going to be as aggressive in their investment as before, but they are re-evaluating how they can connect to consumers on a more personal level.”

Cheques and balances

Beijing has taken various steps to rebuild consumer confidence and increase consumer spending, but efforts still appear to be insufficient and largely on the supply side. The People’s Bank of China took measures to stimulate economic growth by lowering interest rates five times in 2020 and injecting nearly $1 trillion into the economy through various methods such as cutting the reserve requirement ratio and providing direct credit to certain industries.

Beijing has also taken steps to boost investment, both domestically and abroad. In 2020, the government launched a new foreign-investment law that promises to protect foreign investors’ interests in the country while also increasing the number of industries foreign companies can operate in. It also increased its emphasis on key industries such as the digital economy, biomedicine and advanced manufacturing.

“China’s focus on supply-side stimulus has worked for them in the past, but continuing to do so will only result in more trade surpluses and more, mostly unwanted, infrastructure,” says Pettis. “Without demand-side changes, there is unlikely to be any increase in the household share of GDP and by extension the consumption share.”

The government has also launched tax breaks to support small businesses and entrepreneurs. In addition, the government is encouraging people to shop online by providing financial incentives such as coupons and discounts for online purchases.

“During the pandemic, when people couldn’t travel, the Chinese government opened up duty-free stores that didn’t require shoppers to travel abroad to benefit from lower prices,” says Ling. “That policy is going away soon, but they’re really trying to encourage consumers to shop more. These efforts have worked as beauty retailers and wine and spirits retailers have seen higher sales as a result.”

Economic experts have proposed a wide range of other solutions to promote consumer confidence, such as reallocating assets away from the state to households, providing greater support to small and medium-sized businesses, and ensuring consistent policies across the board. But these would require making difficult political decisions and could take years to bear fruit.

One example of going directly to households was seen in the US during the pandemic, where over half of stimulus spending was given to individuals. And while this may have been somewhat successful, with the US consumer confidence index remaining over the 100 point threshold, a similar approach to stimulus in Hong Kong hasn’t resulted in a bounce back of confidence, and it remains unclear whether this would have benefitted China, which provided no such payments.

China’s economic recovery hinges on revitalizing consumer demand, and while stimulating consumer spending may prove successful in the short to medium term, consistency in policies and reforms is required to provide a level of financial confidence in the country’s population.

“Domestic consumption should take over as the main driver of growth as the government aims to pivot towards a more sustainable consumption-led growth model,” says Casanova. “According to the government’s 14th Five-Year Plan, consumption should grow quickly in the coming years, and account for up to 60% of China’s GDP in 2025.”

“There are many historical precedents, even if most economists following China are not familiar with them,” says Pettis. “They suggest two most likely scenarios. The ‘slow adjustment’ scenario is more stable in the short term and will involve a small decline in consumption growth as investment growth declines sharply. The ‘rapid adjustment’ scenario, in which both GDP and consumption contract sharply, with the former contracting far more than the latter, is much more disruptive in the short term but tends to be resolved more rapidly. My best guess is that China will adjust very slowly.”

Selective spending

In the past few years, Chinese consumers have gone from being generally optimistic to largely pessimistic and shifting the wave back the other way is the challenge that needs to be addressed. Consumers’ attitudes towards what they spend money on have changed and perceptions of value have changed.

“My income hasn’t increased in the past few years while the cost of everything has,” says Chen. “I’m still willing to spend money on things like gym classes because I feel like they help me live a healthier life. But at this stage, it looks like I’m just going to have to tighten my belt on other expenses if I hope to achieve my financial goals.”

Discretionary spending has declined largely due to a lack of consumer confidence, and it will be challenging for the government to convince consumers to shift thinking back to how they were a few years ago, particularly if they remain focused on supply-side reforms. But if Chinese consumers were able to fully financially benefit from the sacrifices they have made over the past few decades, namely low wages and long hours, then they would be much more inclined to spend freely.

“A large amount of the results of Chinese economic development over the last few years has actually been enjoyed by the rest of the world thanks to a massive drop in the cost of living, but this drop was driven mainly by weak Chinese consumption,” says Pettis. “If more income were directed to Chinese households, then Chinese production would be less globally disinflationary and Chinese consumers more likely to spend.”