Companies are considering moving production out of China, but how many can successfully do so? The diversification of production away from the “Factory of the World” is happening, at least to some extent. But some industries are finding it hard to break free of the China hold.

With facemasks flying off the shelves at the beginning of the year, it dawned on the world that China was their only source of the pandemic must-haves. While Japan, Taiwan and the United States produce PPE, they did not have enough to even satisfy domestic demand, giving China an arm lock on production when it came to scale. Production is now being ramped up, but industry insiders say that in terms of the raw materials alone, China is probably irreplaceable as the primary source of masks for at least three years.

Over the past 30 years, the world has shifted sizable amounts of manufacturing to China because of its low labor costs and high efficiency. But the production and logistics freeze-ups that accompanied the early weeks of the pandemic caused many companies to realize the danger in concentrating all production in one place.

Different sectors and types of businesses have various reasons why they might want to move, but the virus has underlined the necessity to diversify supply chains away from the Middle Kingdom. This swing away from China was underscored by comments in August from Liu Young-way, the chairman of the Taiwan-based contract manufacturing giant Foxconn that supplies Apple and other tech titans.

China’s “days as the world’s factory are done,” said Liu. “No matter if it’s India, Southeast Asia or the Americas, there will be a manufacturing ecosystem in each,” Liu added. Foxconn started manufacturing Apple’s top-end iPhone models in India for the first time this summer. It is reportedly investing $1 billion to expand one of two factories in the country.

A mask monopoly

Masks and PPE illustrate how China has captured and optimized supply chains over the past four decades, and the extent to which it remains dominant. Once the market demand became clear, Chinese manufacturers responded instantly. Mask production on a daily basis surged eightfold between the start and end of February, up to 76.2 million units, with most of them shipped overseas.

Through the building of ports, railways and telecom networks, low labor costs and a relatively skilled workforce, China has created a manufacturing ecosystem of production that has dominated in a way unmatched in human history. But many countries and businesses have now realized how an over-dependence on Chinese goods involves considerable risk.

“I don’t think people quite appreciated the extent to which they are reliant on China until the beginning of this year,” says Deborah Elms, founder and executive director of the Asian Trade Centre, a consultancy and advocacy group in Singapore. “What caught many off-guard was the extent to which they rely on China for non-obvious things.”

British carmaker Jaguar Land Rover is a case in point. The shutdown of Chinese manufacturing for most of January and February left the company with barely enough inventory to last two weeks. And after Wuhan went into lockdown in late January, prices for the LCD panels used in laptops, smartphones and TVs more than doubled as five factories in the city account for a sizable share of total global production capacity.

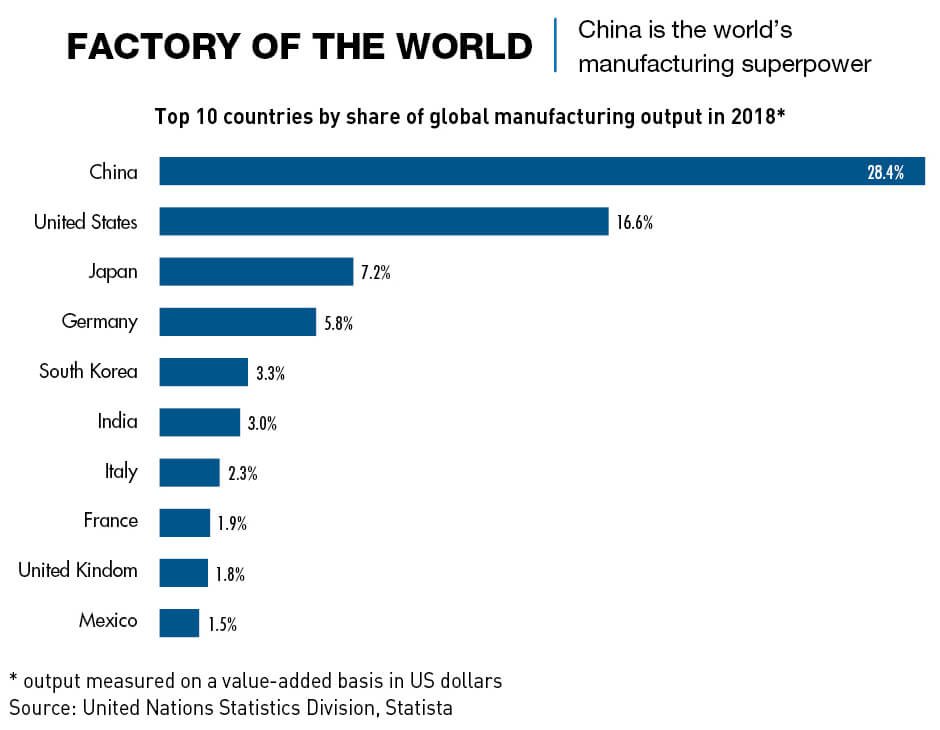

As the world’s largest exporter, China has been continuously upgrading its manufacturing industry in capacity and quality. The Chinese share of global manufacturing value added soared from 1% in 1990 to 28% in 2018, according to a McKinsey study from July 2019. China accounted for 12% of global manufacturing output from 2003 to 2007, but 33% during 2013-2017.

Nowhere is China’s dominance more visible than in electronics. Two-thirds of the world’s smartphones were made in China last year, along with half of all printed circuit boards—the guts of any device—in 2018. And of all the production facilities operated by Apple’s top suppliers in 2019, 381 were in China. Just 58 were in the US.

Swing away

The world’s dependence on China for key parts of its supply chains for everything from face masks to smartphones has shot up on the political agenda—particularly in the United States. This has sparked calls for diversification of China-centric global supply chains.

“There is some hard thinking going on,” says Gerry Mattios, vice president at Bain & Company’s Singapore office. “Companies are thinking about how to de-risk their supply chains so they don’t put all their eggs in one basket. They are appreciating the fact… that shorter supply chains producing closer to where they sell are actually less risky.”

Australia, the European Union, India, Japan and South Korea have all joined in the effort to convince companies to re-route supply chains to some extent, and it appears that Beijing could face a tough fight to hang on to many foreign manufacturers. Japan, for instance, earmarked ¥243.5 billion ($2.27 billion) in April to tempt Japanese firms back home or to other parts of Southeast Asia. In mid-August, US President Donald Trump pledged to punish American companies that move jobs abroad and reward firms with tax breaks for shifting work from China to the US.

Trump’s carrot-and-stick approach underlines how much the threat of politics intervening in business has heightened this year as decoupling between the US and China accelerated. The seismic shocks from the ongoing split are still ongoing.

Global chip and phone supply chains were jolted by US sanctions in August that barred Huawei from buying semiconductors developed with US software or equipment. But how much production will return to the US and other major consumption markets is an open question.

“There are lots of discussions about supply chain diversification, but only a smaller sector is talking about reshoring,” says How Jit Lim, a managing director in Shanghai with consultancy Alvarez & Marsal (A&M).

It would be wrong, however, to characterize the situation as a wholesale and sudden shift out of China. The trend started several years ago, and not everything is going to move. A member survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai in April showed that 70% of respondents were not thinking of moving supply chains due to the virus. Likewise, only 11% of companies responding to a business confidence survey by the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China said they were “considering shifting investment to other countries,” down from 15% the previous year.

The strategic goals of each company determine the extent to which they can, and even want to, move manufacturing out of China, according to Elms from the Asian Trade Centre. Firms in China for the domestic market will approach the debate differently from those using China as a production and supply base for global sales.

“If you’re an American company making products in China and selling into your local market or Europe, it is getting more challenging to do that for political reasons,” says Elms. “For those firms, I would say restructuring or at least thinking about restructuring is important.”

Still chained to China

Moving supply chains out of the world’s biggest manufacturing nation is easier said than done. Many companies find China a hard habit to break thanks to the country’s advanced infrastructure, low-cost labor market and business-friendly regulations. In addition, China has a huge domestic market with rising disposable incomes. Furthermore, its workers already have the technical skills that companies need.

“You can argue that China ought not continue to dominate manufacturing and supply chains. The reality is that alternative locations still cannot match speed, flexibility and often price. Even if an individual item can be created elsewhere, the support ecosystem is lacking—labels, logistics, packaging, warehousing, etc.,” says Elms.

Supply chains were already leaving China in certain industries, including apparel, footwear and textiles, which have shifted to lower-cost destinations such as Bangladesh, Indonesia and Vietnam. Southeast Asia in general is one of several regions positioning themselves as alternatives, but Mattios from Bain says that moves only make sense for specific sectors.

“The answer is not the same for every industry,” he says. “Take an expensive one, like automotive—global automakers do not have a lot of choice about where they can move without having to commit billions in investment to bring the ecosystem with them.”

With thousands of suppliers involved in a vehicle’s value chain, diversifying suppliers to increase resilience involves considerable ongoing costs, says Mattios. Suppliers, wherever they are, need to be able to produce to detailed specifications, and meet strict quality and safety standards.

Other manufacturers, such as of consumer goods, are more flexible, and China’s share of global exports of consumer goods, including handsets and household electrical goods, fell to 42% in 2019 from 46% in 2018. Meanwhile, Latin America and South-East Asia each gained a percentage point to reach 14% and 7% respectively.

Production of home appliances such as refrigerators and air conditioners could move from China to Malaysia and Thailand. But South-East Asia is a mixed bag: worker protests are weighing on Cambodia’s productivity, for instance, while restrictive foreign investment policies and high taxes work against Indonesia. Vietnam is benefiting from the swing away from China in the manufacturing of products such as computer hardware and audio visual technology, according to a recent report from law firm Baker McKenzie and consultancy Silk Road Associates.

Another option is Eastern Europe, which Elms says has a manageable cost structure. “Countries like Poland are well connected and tend to have people with skills, so Eastern Europe is another location that that we’re noticing firms shifting to.”

Closer to home for American companies is Mexico, which emerged as a sought-after alternative at the peak of the China-US tariff war, particularly after the passage of the US-Mexico-Canada agreement (USMCA). Proximity makes Mexico a tantalizing possibility for American firms because companies do not need to wait weeks for goods to be shipped from China.

Fragmenting supply chains

The consensus among most experts appears to be that for many businesses, adjusting supply chains means expanding from China, but not necessarily leaving. What seems likely to emerge is a bifurcation of supply chains: one part would serve China; the other, the rest of the world.

Many companies are pursuing a “China plus one” strategy in Asia, setting up factories in lower-cost countries to serve other markets or hedge against disruption in China, but the approach come with extra costs. “China plus one still has to pass the business case, it’s not free,” says Lim from A&M. “There is risk involved, there’s a lot of friction, a lot of investment needed.”

More investment is an understatement. The total bill for shifting all export-related manufacturing not intended for Chinese consumption out of China could reach $1 trillion over the next five years, according to Bank of America.

There will be a human cost to redrawing supply chains too, which will inevitably raise prices of goods. “The US consumer is going to be worse off,” says Mattios.

The fear expressed by some economists is that higher costs from supply chain changes will lead to a vicious cycle—as consumers’ wallets are hit by rising costs, they will rein in spending and consumption, which reduces demand and leads to economic contraction.

While China is unlikely to emerge unscathed, the trend provides an opportunity to upskill its manufacturing workforce and climb up the value chain—which dovetails with the government-led “Made in 2025” manufacturing initiative. There will inevitably be job losses, but they could be balanced by job creation in other areas.

“There may be fewer textile jobs, but more manufacturing jobs, potentially,” says Elms. “They could be better jobs, so one shouldn’t assume that disruption automatically means no jobs or worse jobs. It just means different jobs.”

China’s vast and still-expanding market ensures it remains a growth opportunity for companies. But many analysts do think the age of China as the undisputed factory of the world is closing—manufacturing will become more fragmented globally, with smaller regional factories working alongside China.

Foreign investment in Chinese manufacturing will likely be largely for the domestic market, as underlined by BASF’s $10 billion plastics project underway in southern China, which will primarily serve local customers.

“We went from a world that was relatively isolated to an interconnected one with global supply chains in China,” says Mattios. “Now we’re heading more toward a multi-polar manufacturing strategy with higher levels of fragmentation. We will have more of ‘China for China’, but also more ‘Poland for Europe’ and ‘Mexico for North America’.”