While the number of yuan-denominated trades are growing, countries are still not noticably increasing their reserves of the currency

Sergio Massa had his eye on China as early as 2011 when he was mayor of a city on the fringes of Buenos Aires. He had just launched the first program in Latin America sponsored by the Chinese embassy to provide free Mandarin classes in public libraries. “We are preparing the future generations for the world to come,” he told local media.

Fast-forward a dozen years and Massa is currently Argentina’s Minister of Economy, with his eyes on a bid for President, and has turned again to China for support. In May, flanked by Argentina’s central bank president and China’s ambassador to the country, Massa announced that Argentina would start to pay for all Chinese imports in yuan rather than dollars.

This amounts to an average of $790 million worth of payments every month, and it seems the primary reason for using the yuan is to relieve pressure on Argentina’s dwindling reserves of the more useful US dollar.

Superficially this development indicates the yuan is gaining ground in its quest to end the dollar’s global hegemony. But while there has been an acceleration in yuan-denominated trade in the past year, the total remains minimal and the real key to a genuine shift away from the dollar depends on countries deciding to hold reserves in other currencies.

“There’s a lot of discussion these days about de-dollarization and whether the US dollar will lose its standing as the world’s sole reserve currency,” says George Magnus, an associate at the China Centre of Oxford University and former chief economist at UBS. “The other side of the coin is often the internationalization of the Renminbi.”

“The question is what exactly does the latter mean? Does it mean people are going to use the yuan more in international payments? Or does it mean it’s going to become much more of a global reserve currency on a par with the dollar and euro? There’s a world of difference between the currency you settle your trade in, and the currency you accumulate your balances in and it all relates to the level of confidence you have in the stability of those currencies.”

Down with the dollar

The US dollar has been the world’s reserve currency since World War II, playing an outsized role in global trade. Indeed, it was not until March 2023 that the yuan dethroned the dollar as China’s most popular currency for settling its own cross-border transactions.

Talks of a move away from the greenback picked up in 2022 after Washington’s Ukraine-related sanctions effectively locked Russia out of the dollar-dominated global financial system—causing concern for China and emerging economies from the Global South.

“In Beijing they were shocked by what the US did in freezing Russia’s dollar currency reserves,” says Yu Yongding, a former president of the China Society of World Economics and director of the Institute of World Economics and Politics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. “They were not prepared for this possibility.”

While China’s leaders have not openly referred to the geopolitical risks of dollar dependence, Beijing has made clear its deep concerns about the vulnerability of the Chinese economy to the dollar’s supremacy during the process of decoupling. Hence its desire to develop alternative systems to hedge against dollar risk. “The hegemony of the US dollar is the main source of instability and uncertainty in the world economy,” the Foreign Ministry declared in February.

The sentiment is shared by other BRICS nations. “Every night I ask myself why should every country have to be tied to the dollar for trade?” Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said on a visit to China in April 2023. “Why can’t an institution like the BRICS bank have a currency to finance trade relations between Brazil and China, between Brazil and all the other BRICS countries?”

The rhetoric has not been confined to China and the Global South. In April French President Emmanuel Macron suggested Europe should reduce its dependence on the “extraterritoriality of the US dollar.” At the same time, China’s economic diplomacy in the Middle East and Latin America has resulted in a steady drumbeat of announcements for arranging more yuan payments to settle international trade.

On a visit to Saudi Arabia in December 2022, Chinese leader Xi Jinping told regional leaders that China wanted to buy more oil and natural gas in yuan. Sure enough, at the end of March, one of China’s biggest oil companies used yuan for the first time to pay for a 65,000-ton cargo of liquefied natural gas sourced from the UAE.

Russia’s economic isolation following its invasion of Ukraine last year prompted Moscow to dramatically increase use of the yuan in trade with China, with the Chinese currency replacing the US dollar as the most-traded currency in Russia in 2022.

When Xi visited Moscow in March, Russian president Vladimir Putin said: “We support using Chinese yuan in transactions between Russia and its partners in Asia, Africa and Latin America. I am sure that these types of payments will grow between Russian businesses and their counterparts in other countries.”

King Dollar

Reports of the dollar’s demise, however, appear to be greatly exaggerated. It was involved in 88% of all foreign exchange trades in April 2022, compared with 31% for the euro, 17% for the Japanese yen and just 7% for the yuan, according to the Bank for International Settlements. The US Federal Reserve estimates that between 1999 and 2019 the dollar accounted for 96% of trade invoicing in the Americas, 74% in the Asia-Pacific region, and 79% in the rest of the world.

The yuan has a growing role in global finance trading but it still remains at less than 10% across all categories. But while the yuan has made inroads in international payments, as it was used to settle 5.8% of transactions worldwide in September, its highest level in five years and beating out the euro, according to data from SWIFT, the dollar still maintains the lion’s share at 42.60%. Additionally, while the yuan’s 7% share of forex trades is a small part of the total, it was nevertheless up from 2% a decade ago.

“If you use the analogy of the solar system to think about currencies, then the dollar is clearly the sun, around which all other currencies revolve,” says Hao Hong, partner and chief economist at GROW Investment Group. “But there are patches of space where other large celestial bodies, further away from the sun can have a significant influence, and here in the Asia Pacific region, the yuan is clearly that currency.”

While the use of a currency in trade is important, far more significant are the currency reserves held by central banks and foreign institutions—primarily to provide stability and to purchase key imports during periods of domestic or global economic crisis. For decades, the dollar has been the currency of choice for these reserves, to the tune of $6.5 trillion at the end of March 2023. The euro is a distant second at $2.2 trillion.

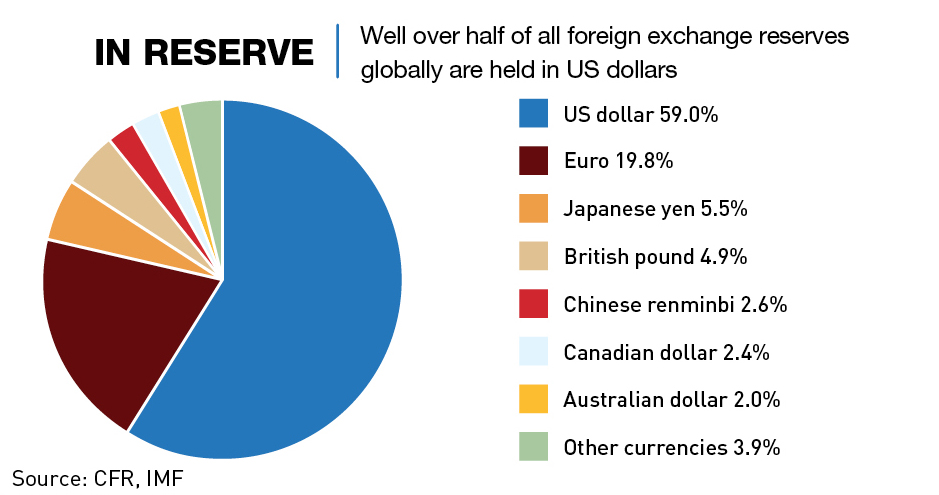

The yuan is among a number of contenders seeking reserve currency status, but pales in comparison with the dollar. Data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) shows the yuan’s share of world forex reserves has more than doubled in the last seven years to 2.58% during the first quarter of 2023, while the dollar fell to 59.02%—the lowest since the euro launched in 1999. The yuan’s growth has far outstripped any other currency, albeit from a very low level.

The nominal amount of international reserves held in yuan stood at $288 billion at the end of March, down from a record $337 billion at end-2021. But in a pool of global reserves totaling $12 trillion—of which nearly three-quarters was denominated in dollars and euros—these figures are negligible. There remains a long way to go for the yuan to reach even the levels of the Japanese yen and pound sterling at a respective 5.47% and 4.85%.

The way it is

The global reserve system has orbited the dollar for nearly 80 years since 1945, from which the US emerged in better economic shape than virtually every other major power. At the 1944 meeting at Bretton Woods, the origins of the dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency began to take shape.

“Under the Bretton Woods system, the dollar was pegged to gold and most other currencies were pegged to the dollar,” says Brad Setser, an economist and senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. “It was a formal acknowledgement that the dollar was going to be at the center of the initial post-war international monetary architecture. Even as we moved out of a world of fixed exchange rates to a world of floating exchange rates, the size of the US economy means a lot of people want and need dollars. There are network dynamics at this point… in the end, if everybody else accepts dollars, you need dollars.”

In the post-war era, the rise of Germany and Japan as major economic powers led to the view that the deutschemark and the yen would rival the dollar, dividing the world into three currency blocs. The yen’s share of global foreign currency reserves did rise in the 1980s, but peaked at close to 9% in 1991 and since has declined to less than 6%.

“It has been Pax Americana nearly all the way since the end of World War II,” says Magnus. The US still boasts the world’s largest economy which remained 42% bigger than China’s at the end of last year and prominent forecasters expect it to stay in pole position for another 10-15 years.

Washington’s willingness to run a current account deficit—the shortfall between the money paid out and money coming in—has also been a key driver. “People have called the dollar’s international role an ‘exorbitant privilege,’ but it’s also an exorbitant burden because it actually means America has to pick up the tab for everybody else,” says Magnus.

Deep, liquid and open financial markets have also ensured the dollar remains the de facto global currency. The total value of the US stock market stood at $40.5 trillion at the end of 2022, nearly four times bigger than second-placed China’s valuation of $11 trillion. “The US has capital markets that nobody else can even approximate in terms of depth and breadth. It has the rule of law. And it still commands trust for the most part,” says Magnus.

Something different

The idea of de-dollarization has been on the radar for at least 20 years. Yu recalls how momentum picked up after the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, which led to his participation in a United Nations expert commission on reforming the US-dominated international monetary and financial system.

“I participated in the commission for two years and we had many meetings without any result, because the US economy stabilized, the dollar stabilized and the US current account imbalance stabilized, so it slipped out of people’s minds,” says Yu. “Now, fears over how the US froze Russian assets have reignited talk again.”

The sanctions against Russia provide a cautionary reminder of the power Washington and the dollar wield in the current monetary era, according to Hao. “The way the US froze Russian central bank assets and disconnected Russian banks from SWIFT last year, coupled with the US debt limit fiasco in June, have got people thinking, ‘Perhaps now is the right time to look for a new alternative currency.’ That’s why there’s so much talk in this space.”

The global reach of the dollar extends the impact of US sanctions, which has been felt by the likes of Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Syria and now Russia. “Most dollar payments will ultimately involve a payment system that touches an American bank when they get cleared, and when it touches an American bank, the sanctions apply,” says Setser.

The debate over whether the dollar will lose its standing as the world’s sole reserve currency overshadows the problem that there are few good alternatives.

The yuan has made inroads in overseas trade settlement, but the consensus is that it has little chance of taking over as the dominant reserve currency anytime soon. The yuan’s status as a controlled currency is also a significant long-term obstacle. Policymakers in Beijing exercise control over the exchange rate which reinforces the view that the yuan can be a risky asset.

Backed by the dollar’s reputation, US treasuries are seen by large investors like central banks and sovereign wealth funds as a ‘safe haven’ to park hundreds of billions of dollars of wealth, as protection against balance of payments crises.

This is not the case with China debt, as underlined by a recent sell-off in Panda bonds by foreign investors who feared Beijing’s ties to Moscow could potentially expose overseas holders of Chinese assets to international sanctions. There needs to be confidence in the system underlying the currency before people will be happy to hold it. “It is very hard to create a reserve currency, without attractive reserve assets,” says Setser.

Building the yuan into a serious challenger to the greenback essentially requires other countries to decide to accumulate China’s currency—something that Magnus says can practically only happen if China imports more than it exports, thereby giving out yuan, or if it abandons capital controls, so that domestic firms and citizens can freely invest yuan abroad. “What we’re really asking is, is China ever likely to run big trade deficits on a permanent basis? I don’t think that looks likely,” says Magnus.

“No one to my knowledge is actually issuing a lot of yuan-denominated bonds to finance their current account deficits,” says Setser. “Deficits are still financed in dollars, pounds, rupee or lira, so we are a long way away from a world where the yuan is an important source of financing for countries running a current account deficit.”

Neither will these structural issues be solved by a government-backed digital yuan. Issued directly by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the electronic currency remains niche with ¥13.61 billion ($1.88 billion) in circulation at the end of last year—equivalent to just 0.13% of all cash circulating in China.

It remains unclear how the digital yuan might help Beijing improve the global standing of its analogue equivalent, as a programmable central bank digital currency would allow governments to trace all transactions and dictate which purchases could be accepted—a level of control that would be anathema to many countries. There are also concerns, though, that a digital yuan could be useful in helping Beijing evade international sanctions, such as those applied to Russia as a result of the invasion of Ukraine.

But Yu is circumspect about the prospects of the digital yuan. “We have stopped talking about this,” he says. “The existing options available through Tencent’s WeChat and Alipay from Ant Group are very convenient. So, people would ask why we need a digital currency?”

The euro made up 19.77% of forex reserves held by central banks in Q1 2023, but its chances of becoming the primary reserve currency have come and gone, according to Hao. “It’s been around for decades now, so 20% is pretty much it. The euro has tried for nearly one-quarter of a century already so I think we should give the yuan the same amount of time too,” he says.

Like the US and the dollar, the European Union and the euro have the benefit of rule of law, openness and transparency, and deep capital markets. But euro-skepticism has, to some degree, hobbled greater adoption of the euro, which remains an imperfect fiscal and monetary union. “There is still a reservation about the euro system in a way that there isn’t about the dollar system,” says Magnus. “People really understand what the US is and what it represents.”

There is a possibility that a new multilateral currency initiative—like the BRICS currency, an idea floated by Brazilian president Lula in April—could be an answer to the current dollar hegemony. In August 2023, the group announced a number of new members that would join in early 2024, this includes Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia and economic heavyweights Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

But for many it is still unlikely to be the answer, given the countries that form the backbone of the growing geopolitical grouping are too disparate to underpin a cohesive currency.

“The expansion of the BRICS certainly has geopolitical intent,” says Magnus. “As a group though, it is even less economically coherent and still further away from the kind of currency area that’s compatible with a common currency that could rival or supplant the dollar. They might try to use the yuan a bit more to invoice one another in trade but ironically, they all use and need to accumulate financial balances in US dollars.”

No credible replacements

Virtually all of these options lack credibility. Even though China was the largest trading partner to twice as many countries as the US last year, the greenback remains the world’s global settlement currency because of its stable value, the size of the American economy and the US’ geopolitical heft. “The trust and confidence that the world has in the ability of the US to pay its debts keep the dollar as the most redeemable currency for facilitating world commerce,” says Setser.

It is financial market participants that ultimately determine a currency’s status, and it is clear they have found the yuan lacking when it comes to reliability, convertibility, transparency and control over their finances. The renminbi’s status as a reserve currency has been impeded by Beijing’s unwillingness to free up its exchange rate, allowing the currency’s external value to be determined by market forces, and to fully open the capital account. Moreover, China’s financial markets are limited, with a number of constraints such as a rigid interest rate structure.

“The blockages on capital outflows, and misgivings over the trust and respect of China’s legal system and its capital markets are also a serious problem,” says Magnus.

Here to stay

China’s central role in the global economy means de-dollarization in international trade and finance will inevitably continue as the yuan chips away at the commanding shares of the dollar and euro. But this does not necessarily spell the end of the greenback’s hegemony.

Setser points to how the launch of the euro in 1999 reduced the dollar’s use for trade within Europe, but has not diminished US global power. “If you’re the government of China, Iran or Russia, it may be unsatisfactory that the dollar is still the first amongst equals in terms of global currencies, but it is what it is,” says Magnus.

The yuan’s acceptance as a reserve currency is likely to be much more measured—growing in importance in the decades to come but unlikely to dethrone the dollar. “No other country can kick the dollar out as the de facto international reserve currency,” says Yu. “Only America. It is theirs to lose.”