China’s plans for future growth revolve around future-facing ‘new productive forces’

Three is said to be a magic number, but for good measure the Chinese government is putting its faith in 300—the number of reforms it wants to carry out over the next five years. Outlined after a major conclave of the Communist Party’s Central Committee in mid-July known as the Third Plenum, the reforms cover everything from the economy and national security, to culture and social issues.

China’s new vision of economic reform clarifies Beijing’s strategy for economic growth and a more substantial position in the world, but it involves some significant issues, including putting it at odds with the Western world and potentially limiting economic growth in favor of national security and control.

The reform plan comes at a crucial juncture for the economy, which is battling structural imbalances, brittle confidence and heightened geopolitical tensions. Questions continue to swirl around specifics, implementation and the implications for China’s economy, foreign policy, society and R&D.

“When I hear the word reform, what does that actually mean?” asks Philippe Le Corre, a senior fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis and author of China’s Offensive in Europe. “I lived through the years of China’s open-door policy in the 1980s, the 1990s and even the first decade of the 21st century: people in China were enthusiastic and much more entrepreneurial than they are now. There is a feeling that business is not as positive as it was.”

Control versus growth

The overarching theme of the Third Plenum included an emphasis on so-called “high-quality economic development,” led by investment in innovative industries and consumption. The meeting also called for strengthening the resilience and security of industrial supply chains in light of rising geopolitical tensions, re-emphasizing the importance of the private sector, improvements to the pension system, strengthening the efficiency of the SOE system and measures to boost domestic consumption.

Key to creating fresh growth will be the digital economy, and there are ambitions to scale it up. A three-year action plan was released in April to nurture and attract digital talent and workers, and another roadmap in August to promote low-carbon development of digital industries.

Cultivating ‘new quality productive forces’ sits at the heart of China’s pursuit of a more resilient, forward-looking economic structure amid growing uncertainties. The concept is often taken to mean high-tech manufacturing, green energy industries and cutting-edge technologies that will eventually be mission-critical for a future economy.

The strategy marks a shift in China’s long-standing industry policy, as it aims to transform the country into a disrupter through technological breakthroughs and leadership of strategic industries such as clean energy and electrified transport.

“New quality productive forces are about advanced productivity freed from the traditional economic growth mode and productivity development paths,” says Bruce Pang, chief economist and head of research for JLL in Greater China. “They represent the innovation that traverses beyond traditional limits. Aside from emphasizing the use of cutting-edge technology to reshape industry ecosystems, they also aim to take advantage of China’s role as a global leader in manufacturing and export, showing the country’s ambitions to ascend the global value ladder.”

The emphasis on advanced manufacturing that embraces digitalization and resilience would appear to bear many of the same hallmarks as ‘supply-side reform.’ While there is some alignment, Rory Green, chief China economist for GlobalData TS Lombard, argues that new quality productive forces are not a simple rebranding of supply-side reform. “There’s more in terms of pushing for new ways of manufacturing,” he says. “The just-in-time models pioneered by Japan are fading out, and we’re seeing a new automated, IT-led production model with a highly mobile workforce that’s able to produce high turnover.”

Industry baby

China’s tilt toward an innovation-driven economy comes against a backdrop of a worsening macroeconomic outlook. The country faces issues with a property market collapse; stock and bond market drops growing local government debt; challenges over trade issues; weak investor confidence; and sluggish consumer demand.

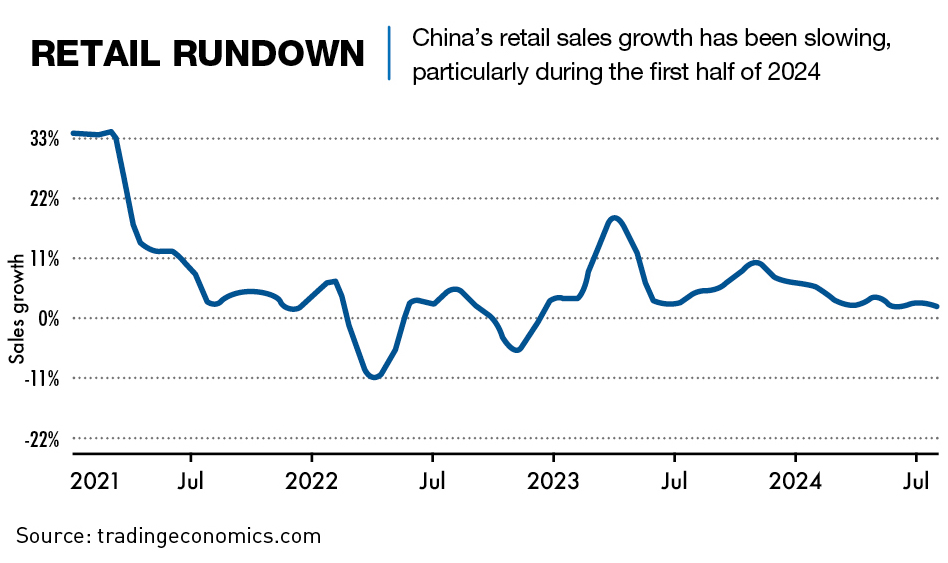

Consumer reluctance to spend remains the foremost constraint on near-term growth. A survey by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) in Q2 found that 61.5% of city dwellers wanted to increase the amount in their savings accounts, while only one-quarter wanted to consume more.

China’s recent economic wobbles have raised questions about whether the soft demand is cyclical or whether the problems run deeper. China is transitioning from an “easy to heat, difficult to cool” economy to an “easy to cool, difficult to heat” one, said Huang Yiping, an influential economist and member of the PBOC’s monetary policy committee, in May.

There have been calls for Chinese policymakers to change tack in their strategy of focusing on investment and neglecting consumption, with policy ideas ranging from setting a compulsory target for inflation to stepping up spending to address weak consumption. But at the same time, providing higher income for the consumption economy leads to higher labor costs which could impact competitiveness on a global scale.

Beijing’s bet on new quality productive forces also carries some risks. While Chinese R&D into technologies such as batteries and renewable energy has helped it claim leadership in these industries, significant investment in other critical technologies such as semiconductors has been less successful.

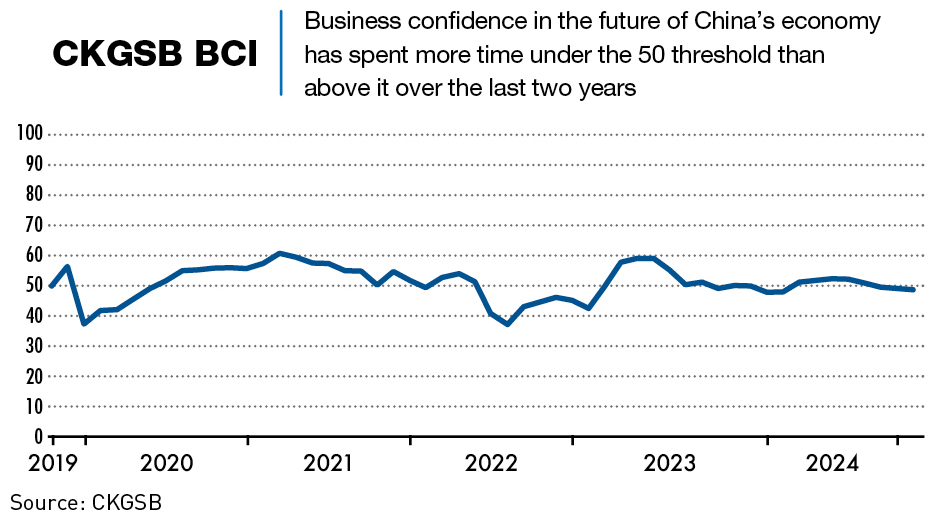

Confidence is also down across the board. Consumers, investors and private companies are all reining in spending to some degree. The pessimism has been reflected in CKGSB’s Business Conditions Index, a gauge of business sentiment that fell to a year-to-date low of 48.8 in July—the second month in a row it fell under the confidence threshold of 50. Brittle confidence has not been helped by a malaise in youth unemployment, with 17.1% of the roughly 100 million Chinese aged 16-24 out of work in July, a jump of around 4% over the previous month.

The gloom is most visible in real estate, a sector that remains in dire straits more than three years after Evergrande lurched into crisis. The unprecedented property recession has dragged on the economy, and left an estimated 20 million homes unfinished and up to 60 million unsold. While Beijing rejected a ¥6.93 trillion ($977 billion) housing rescue plan pitched by the International Monetary Fund, it did reiterate at the third plenum that there should be a focus on ensuring ample supply of affordable housing and rental housing, compared with the previous emphasis on commercial real estate.

But there was nothing on how this would be achieved, nor what efforts would be made to address the current property market decline. Instead, Beijing’s policymaking to stem the property decline has been a series of experimental and incremental steps. In May, the PBOC said it would provide ¥300 billion in cheap loans to help local state-owned enterprises (SOEs) buy unsold homes to turn into affordable housing, which has not yet yielded much success.

China’s new economic approach will also need to confront the epochal demographic challenges of a shrinking and aging population, as well as a declining birth rate, which have helped reduce the working-age population of 16 to 59 year-olds by more than 60 million from its peak in 2011 to 875.56 million in 2022.

Inside out

Even as Beijing touts new quality productive forces as the future of China’s economy, it will need to contend with a West already wary of China-made products in fast-growing industries. Chinese dominance in future-facing industries has put it in the crosshairs of other governments. For example, Canada has followed the US and EU in imposing high tariffs on imports of Chinese electric vehicles (EVs).

Neither is the skepticism over Beijing’s intentions confined to Western governments. Countries that once saw China as a customer now see a competitor. “The decade-long support from the Chinese economic boom has disappeared,” Mexican Finance Minister Rogelio Ramírez de la O complained in July. “China sells to us but doesn’t buy from us and that’s not reciprocal trade.”

The mistrust partly boils down to China’s more assertive foreign policy in recent years, according to Le Corre. “Since 2020, China’s foreign policy is unfortunately not seen positively in the West,” he says. “For example, all the benefits of the Belt and Road Initiative have faded away in Europe. The situation may be different in developing countries, but how many governments have actually thrown their full support behind China’s global rise?”

Leading the pack

Despite the headwinds, China’s economy is still, according to official projections, expected to expand by a level almost any other major country would envy. There are reasons for cheer, such as the staggering progress China has made in technologies deemed mission-critical for economic development going forward.

Green energy is one example. China already controls 80% of the global solar market, occupies 60% of the market for wind turbines, and produces three-quarters of all lithium-ion batteries. And with China’s installed solar and wind capacity on track to reach 1,200 GW by 2025 — five years ahead of schedule — the country will continue to be a clean energy superpower with a manufacturing base that underpins renewables rollout in the rest of the world. The country also already dominates the production of green hydrogen, a non-polluting fuel made using renewable energy sources that are seen as key to cutting emissions in smokestack sectors such as steel, cement and petrochemicals.

China’s new energy vehicle (NEV) industry, meanwhile, is set to contribute as much as 4.5-5% of GDP by the end of this decade, reflecting its massive growth potential as consumers increasingly opt for EVs, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

Other bright points that will help China overcome its issues include digitalization and artificial intelligence (AI) deployment. Greater AI implementation in industries ranging from automotive, transportation and logistics, to manufacturing, enterprise software, healthcare and life sciences could create $600 billion of new economic value annually in China, according to McKinsey.

Measuring the Middle Kingdom

As China endeavors to recalibrate its economy toward sectors with high productivity, gauging the success of the strategy will require close analysis of not only GDP growth but also confidence and overall policy direction.

Top of mind for policymakers will be scaling up technological innovation and new quality productive forces, followed by maintaining GDP growth at 4-5%, with the overall goal of structuring the economy without too much disruption. But consumption will also be a key metric to observe.

“I think I would be more focused than Beijing on the consumption side—if I saw the savings rate trending down, and the share of consumption trending back up, that would certainly imply confidence and employment,” says Green. “To me, that would be the most encouraging sign.”

China’s centralized, state-led approach will also need to be monitored to ensure Beijing lives up to its word of ensuring a level playing field for private and foreign enterprises. “The plenum’s statement makes a unique reference to the central role of the party-state in running the economy,” says Le Corre. “Unlike in the 1990s, the state sector is growing, not reducing. National security is over-emphasized which is not a good signal to foreign investors—many have become static as best, waiting for better news.”

“Foreign investors will need to treat China like any other big, opaque country with a big market, such as Brazil or Indonesia: do it, but with caution,” says Anne Stevenson-Yang, founder and research director of J Capital Research.

Opaque outcomes

China is clearly playing a long game with its economic pivot, building on strategic policies announced in the past few years. But while Beijing’s goals are clear, the specifics of achieving the ambitions remain murky and will likely remain so for the foreseeable future.

The nature of the Chinese system makes it difficult to predict the efficacy of the plans, their consequences and how exactly they will play out in the wider international context. Still, what is clear is that China’s leadership is aiming for something specific, and that is likely a political, rather than a business goal.

“Given that the final communiqué from the Third Plenum focuses on ideology as opposed to the economy—despite various structural problems and cyclical downturns, it is evidence of the fact that politics is what drives the Communist Party’s leadership,” says Le Corre.

“China has to do what it thinks best,” says Anne Stevenson-Yang. “Back in the 1990s and early 2000s, what was thought best was a big party for foreign investors. The party is over now, and good luck to them.”

Digital Directives

China’s plan to enhance the integration of digital technologies

in business practices across the country by 2026

- Innovation:

- Leverage advanced information technologies to drive innovation in business models, products and services

- International Cooperation:

- Expand channels and platforms for digital commerce

- Promote Silk Road e-commerce and join the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA)

- Foreign Investment:

- Attract foreign investment by easing restrictions in sectors like telecommunications.

- Facilitate cross-border data flow for qualified foreign enterprises.

- Consumer Spending:

- Boost digital consumption through incentives in the digital, green and health sectors.

- Create new consumption scenarios in experiences, entertainment and healthcare.

- Rural Development:

- Implement high-quality rural e-commerce projects.

- Enhance logistics and postal networks for rural e-commerce growth.

- Cross-Border E-Commerce:

- Promote standardized development and increase variety of global goods available to Chinese consumers.

- Encourage foreign SMEs to access the Chinese market through streamlined online channels.

- Openness in Digital Commerce:

- Expand Silk Road e-commerce partnerships with 31 countries.

- Establish bilateral cooperation mechanisms and a global e-commerce cooperation alliance.

- Global Engagement:

- Actively participate in e-commerce negotiations at the WTO.

- Strengthen dialogues within international organizations (e.g., BRICS, G20, APEC).

- Advance talks to join the DEPA to enhance global e-commerce collaboration.

Source: english.gov.cn