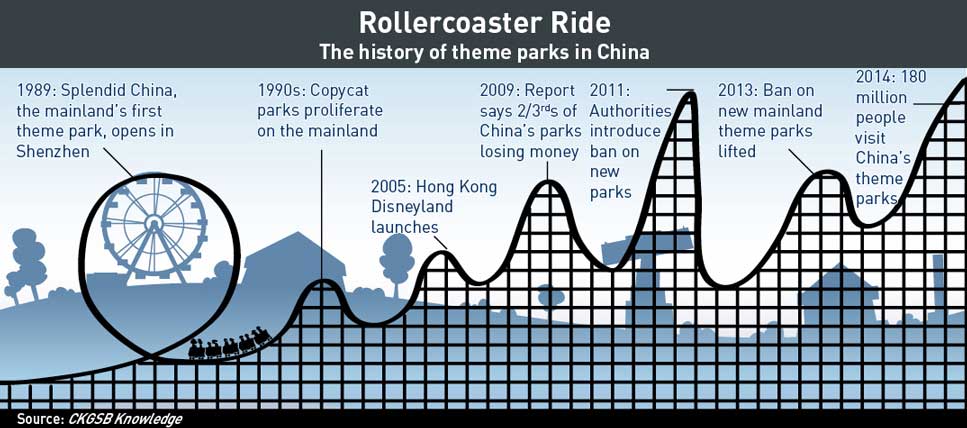

Theme parks in China are in take-off mode once again, but could some be heading for a big drop?

When the gates of Disneyland Shanghai open in 2016, visitors will be treated to the tallest towers of its largest and most interactive castle. It is to be located in the biggest theme park Disney has ever built, with park grounds sprawling over 30,000 acres, or 3,000 more than Florida’s own Disney World. As of April 2014, Disney and Shanghai Shendi Group had committed to pouring approximately $5.5 billion in total into the park. But Disney’s will be far from the first such castle to market on the mainland.

For a decade and a half, the unfinished, skeletal ruins of a strangely familiar fantastical fortress peeked out over the horizon northwest of Beijing. There, in 1998, all activity at the Wonderland Amusement Park suddenly died (along with investors’ hopes) when a dispute between landowners and developers halted construction. The increasingly infamous remains were finally razed in 2013, the same year China’s central government also lifted a nationwide ban on new theme parks.

Since then, with numerous parks opening, or being slated to open, across the country, concerns have arisen over whether the industry was headed toward another bubble like that seen in the previous decade, or the decade before, when many purported parks proved nothing more than copycat knock-offs at best and backdoor real estate deals at worst. But Chris Yoshii, Global Director in Asia for AECOM Technology, says that interest in China’s park sector remained substantial thanks to real market demand from a growing, cash-flush middle class.

“I think in the future we’re going to see a big increase in investment in this area,” Yoshii says. “I’m hopeful most of it will have a positive outcome, but I’m sure there’s going to be a few that are just… you’ll kind of wonder what they were thinking.”

From Anaheim to Shenzhen

The modern theme park industry began in America with the 1955 opening of Disneyland in Anaheim, California. But it would be over three decades before the first theme park launched in mainland China. In 1989 Overseas Chinese Town Group (OCT) finished construction in Shenzhen of Splendid China, a park featuring miniature replicas of many famous Chinese landmarks.

Splendid China was a roaring success, and from the late 1980s to 2005 saw 50 million visitors, took in RMB 2.6 billion in revenue and generated RMB 1 billion in gross profit, according to one academic study of the company’s performance. Some parks that launched nearby soon after Splendid China’s debut also became wildly popular.

In 2011 Winshang News cited Zhao Huanyan, Chief Intelligence Expert at Huamei, as having said that China had more RMB 150 billion ($24 billion) tied up in more than 2,500 theme parks, of which 70% were lossmaking, 20% were breaking even and the rest turning a profit. By contrast, statistics from the International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions (IAAPA) state that the US has over 400 theme parks.

But the early successes in Shenzhen built up false expectations among adventurous entrepreneurs elsewhere, who concluded that all they had to do to achieve similar profits was throw up a few rides outside of town. As parks proliferated around the country, many found themselves unable to attract repeat visitors and were soon shuttered. According to the Themed Entertainment Association/AECOM report for 2009, two-thirds of China’s theme parks were losing money, with billions of yuan either already lost or at risk.

Markus Schuckert, an assistant professor at Hong Kong Polytechnic University’s School of Hotel & Tourism Management who teaches and has written extensively about theme parks in Asia, says that originality was and still is a challenge even now for many Chinese parks.

“It’s still the theming, it’s the branding, it’s the storyline,” Schuckert says. He explains that Chinese parks can come off as less aggressive than their western counterparts because they focus less on thrilling, high-G-force rides, which exert pressure on riders. Instead they’ve opted to emphasize a more multimedia-based experience with soft rides that an entire family can enjoy. But that doesn’t make a signature brand and intellectual property any less important: Asian parks also tend to rely more heavily than other regions on merchandise, which Chinese consumers consider both highly collectible proof of their experience and souvenirs to bring back for friends and family.

That helps explain the widespread failure of China’s theme parks in the first decade of the millennium, though it was by no means the only culprit. Most parks were also far outside of town, which minimized property costs but made many parks nigh-impossible to reach. When visitors finally arrived, they found parks that were nothing more than copies of those in Shenzhen. Bad management and corruption further undermined park quality and visitor experience.

These troubling practices all came to a head in 2010 on the Space Journey ride at the Ecoventure Valley park when the ride malfunctioned, killing six people and injuring 10 more. Compensation and an apology from the chairman of OCT wasn’t enough to undo the damage done to the industry’s reputation. It had lost what Schuckert considers the other two prerequisites to the sector’s success: consumer satisfaction and a feeling of safety and security.

Lessons Learned

Even Disney’s performance in greater China hasn’t been flawless. When Hong Kong Disneyland launched in 2005, it was really almost half a park—a lack of attractions made the grounds look empty, and more had to be added post launch. The Hong Kong outfit only began turning a profit in 2012, when Disney was already working to seal the deal on a Shanghai park.

Shanghai’s park makes it clear that Disney learned from its mistakes in Hong Kong and won’t rush things—earlier this year Bob Iger, CEO of Walt Disney, told investors it would launch in spring 2016, likely so it will open during warmer weather. The grounds—now entering the final stretch of construction—are huge, but fully outfitted with plenty of rides, and are located in-between Pudong International Airport and the Shanghai city center. Disney is betting on big crowds from people seeking something special, and locals seemed set to oblige.

“Most parks are quite alike in China,” said a woman, surnamed Zhu, voicing a common complaint among those surveyed. While she hoped Shanghai’s park would charge less than those abroad, others didn’t mind if it meant less of a crowd.

One Mr. Li suggested better service from less sullen staff would go a long way, and most said they were glad for a park that could guarantee safety after an accident the previous month in Henan, where a rocking boat attraction had flung 19 visitors free of their seats and clear of the ride. And that was before a ride in Wenzhou killed two at the Zhejiang Pingyang Amusement Park in early May.

As Disney’s opus takes shape and restrictions on park approval have eased, attention has been drawn to a variety of other parks on the mainland that run the gamut from savvy to unsettling. The theme park concept fits nicely into the future of a consumer- and services-driven economy envisioned by China’s top officials. And China’s massive population, as elsewhere, makes the potential profits all the more alluring.

About 180 million people visited China’s theme parks in 2015 according to estimates from the IAAPA, and Yoshii says AECOM expects the theme park market to double over the next five years. Little wonder, then, that Disney isn’t the only one looking to set up shop on the mainland.

Foreign-planned mainland parks include the $2.4 billion Dreamworks Center in Shanghai, a $3.3 billion Universal Studios park outside of Beijing and a Six Flags park in Tianjin. These projects, backed by experienced Western theme park firms and well-situated within or near top-tier cities where discretionary spending is typically higher, all look relatively safe.

Local Adventures

Local developers run a wider gamut, and it’s easy to laugh at some of the more eyebrow-raising concepts on display and in the works. One widely-cited online review of a Hello Kitty-themed park in Zhejiang complained of ho-hum rides and wretched food. The chief executive of the main investment firm behind a planned Titanic theme park—replete with simulated iceberg collision—told Reuters that “[w]e will let people experience water coming in by using sound and light effects… They will think: ‘The water will drown me; I must escape with my life’.”

Not all the drama is hypothetical. Real estate conglomerate Dalian Wanda grabbed headlines with the debut of the nationalist-themed Han Show performance at its new Wanda Movie Park in Wuhan, and Chairman Wang Jianlin has plans to invest RMB 200 billion ($32 billion) in 12 theme parks around China—including in Guangzhou and Shanghai, where he hopes to take a bite out of visitor rates at the Disney parks nearby in Hong Kong and Shanghai. Michael Cole, Shanghai-based head of real estate intelligence site Mingtiandi, is less certain of Wanda’s plans for amusement park domination.

“That looks fairly challenging to me,” Cole says. “Part of what’s attractive about these places is the branded experience. Wanda’s trying to create their own brand, which is something they haven’t really done before [except with malls].”

Schuckert, too, is skeptical of Wang’s publicly stated ambition to use a dozen Wanda parks to cannibalize the target demographic of Disneyland and other foreign-backed ventures, particularly when compared to more established domestic players in the sector who have successfully crafted enjoyable, well-branded parks that offer visitors a unique experience.

“If Disney would have opened Disneyland in the US in four or five different corners [of the country], would it be so amazing to go to California or Orlando?” Schuckert asks. He points instead to newcomer Chimelong Ocean Kingdom in Guangdong province—the most-visited water park in the world in 2013, with visitors up 7.5% year-over-year, according to AECOM—as a paragon of park planning.

Other major Chinese theme park outfits include OCT Parks China, whose attendance in the same year was up 12.7% to 26.3 million visitors; Fantawild Group, which hit 13.1 million visitors, up 42.7%; and Haichang Group, which saw 10 million visitors, an increase of 7.4%. These three firms ranked 4th, 9th and 10th, respectively on AECOM’s latest list of top 10 theme park groups worldwide.

Fantawild in particular appears to have beaten Wanda to the punch in many mainland locales. While the firm is a heavyweight in the domestic parks industry, none of Fantawild’s attractions are located in first-tier cities. But the total profits from its many second and third-tier parks were enough to vault it into the ranks of global industry leaders for the first time in 2013.

Other headline-making plans from the past year are still amorphous at best. These include collaborations between local and foreign companies, such as vague plans from DMG and Valiant to build superhero-themed parks. Citic and Village Roadshow recently announced plans to jointly develop a panda-themed park in Chengdu, with five more locations around China being mulled.

If You Build It…?

Much like the first success stories out of Shenzhen, impending profits generated by big-name park groups’ China ventures have planted copycat dreams in the brains of many local government officials around the country. That’s not to say demand isn’t increasing; today there is a growing middle-class cohort willing and able to pay RMB 200-400 ($32-64) for a memorable theme park experience. That kind of consumption, says AECOM’s Yoshii, was unthinkable even just five years ago. But he cautions that the latest flurry of activity isn’t solely a matter of market fundamentals.

“There’s also the political push, that different cities want to promote themselves and they see theme parks as one of the things on their list. If they want to be an international city or a first-tier city, they’ve gotta have one,” Yoshii says. Local governments and developers aren’t necessarily aware that a good theme park is a capital-heavy, long-term investment that can take close to a decade to start paying off, he says. Cole of Mingtiandi agreed, and pointed to a similar bubble in America, long since popped.

“They did that in the US a bit too. Everyone thinks it’s a great idea to have an attraction that pulls people to their city and they all want to put their city on the map, and they tend to often fail,” he says.

There is also the issue of developers using theme park development as a backdoor for official endorsement of other endeavors. Schuckert says that when development projects in China are large enough, developers are required to provide value-enhancing elements, such as shopping complexes, together with another feature of either cultural or entertainment value. That is where theme parks often come in—as a box to be ticked on the road to approval.

“The primary goal is not to make revenue, it’s just to tick the box in terms of a long list of requirements,” Schuckert said. “This a part of the development game. So yes, there is still potential for a bubble.” That potential may have been heightened by the recent go-ahead from the central government to allow theme park projects valued at less than RMB 5 billion ($800 million) to be approved. This policy change may set the stage for another rash of unprofitable and quickly shuttered theme parks.

That stands in contrast to the proven and profitable park models already on offer from firms both local and global. With these juggernauts eyeing further expansion, the market for theme parks looks to soon be saturated. Big names like Disney and Universal, or Fantawild and Chimelong, will likely thrive due to their backing and experience, while theme parks without a strong concept and marketing will dissolve as quickly as they were thought up.

China’s theme park industry will almost certainly thrive in the course of the next decade. But observers can expect to spot plenty more spectral half-finished park grounds popping up along the way.