China’s lower-tier cities are growing fast, with their consumption potential, development and affordability, will they be able to offset China’s slowing economic growth?

China last year recorded its slowest economic growth in 28 years, but for leading e-commerce player Pinduoduo, it was boom times, with business up 234% for the year thanks to a largely ignored market—China’s vast rural regions and smaller towns and smaller cities, termed “non-first tier cities”.

Pinduoduo is an online shopping platform that allows users to participate in group shopping deals, which have become a very hot area in China’s online economy. “More players are looking at lower-tier cities and they’re also trying to mimic what Pinduoduo is currently doing,” said the company’s CEO Huang Zheng. “The greater emphasis given to the lower-tier cities by our peers is also helping awaken the underlying demand for consumption that has been dormant in these cities.”

His peers include Alibaba, China’s biggest e-commerce player, which is also tapping into the potential of smaller cities, saying in an earnings call in March that more than 70% of the increase in its annual active users came from these low-profile regions.

China has a population of over 1.3 billion, and well over half of them live in urban areas outside of first-tier cities. Tier-one cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen are the most-developed and the largest of the cities across China with populations between 15 and 25 million. But lower-tier cities make up 50.3% of China’s population. More than 100 cities in China have a population of more than 1 million, and most of them are unknown outside of the country.

Many of these “smaller” cities are in fact still massive by most international standards. Lanzhou in Northwest China, for example, is considered a lower-tier city by Morgan Stanley’s standards, but still has a population of 3.7 million.

Despite the popularity of the city-tier system, the Chinese government does not have official criteria on how the classification of a city in a specific tier is determined. Cities are loosely classified based on various factors such as their GDP, population size, and level of infrastructure, with four tiers making up the city-tier system overall.

After decades of playing second fiddle to the first-tier cities near the coast, numerous smaller cities are now beginning to thrive, and in many ways they offer better opportunities for business growth than the mature metropolises do.

“In our big picture now, these so-called lower-tier cities, they will be basically the major driver of growth in China in the next 10 to 15 years,” said Robin Xing, chief China economist at Morgan Stanley in an interview with CNBC in March.

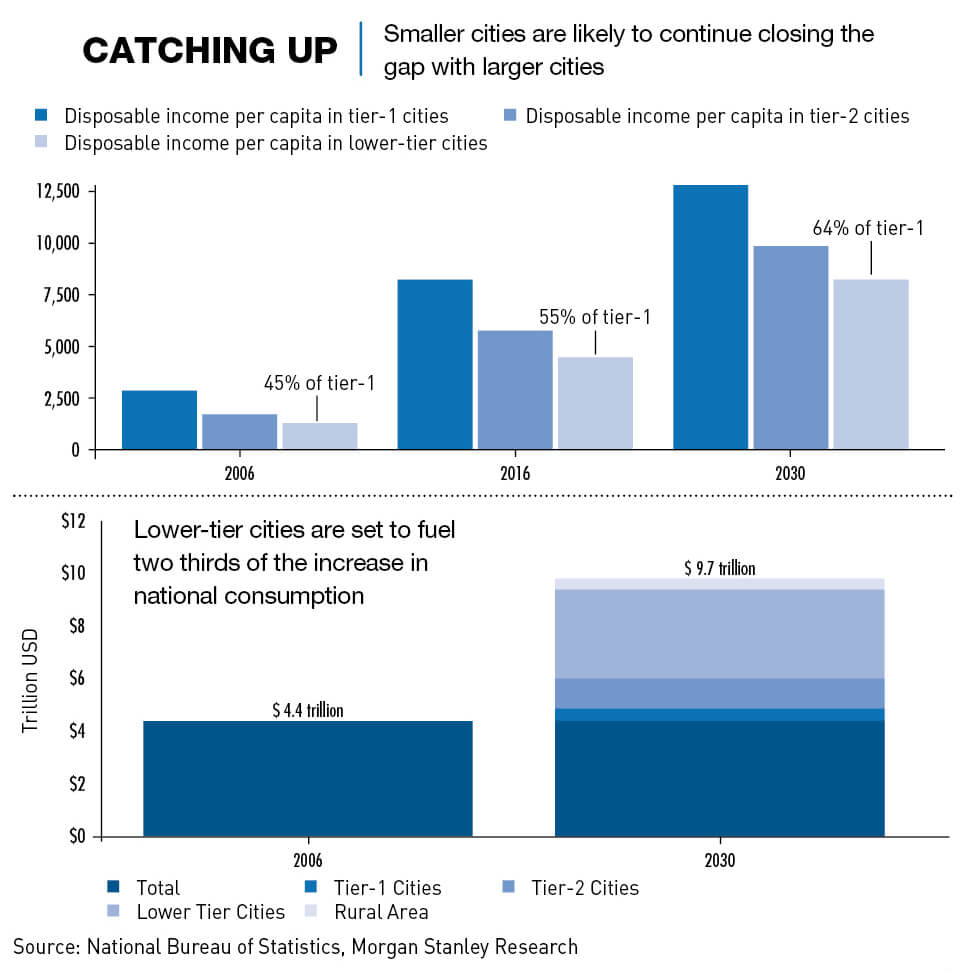

According to Morgan Stanley, consumption in China’s smaller cities is expected to triple between 2017 and 2030, due to population growth in those cities, favorable government policies on offer to enterprises that set up there, a rise in household incomes, and higher consumer spending.

China’s “new first-tiers”

The rise in population in lower tier cities is being fueled by two factors, movement from rural areas as well as people migrating from first tier cities.

According to United Nations estimates, more than 160 million people in China are expected to move from rural to urban areas over the next 15 years, with three-quarters of them going not to the major coastal cities, but to lower-tier cities inland. Many of them would probably still opt to move to the first-tier megacities if they could, but because of high living costs and inflexible household registration policies, an increasing number of people are choosing smaller cities instead, especially cities close to the richer first-tier ones.

“One of the things we’ve seen over the last three to four years is a trend of reverse migration, with people who had moved to first-tier cities to start their careers now moving to smaller cities to help companies establish regional offices,” says James MacDonald, Senior Director of Research in China at Savills.

Lower-tier cities have been seeing a large amount of growth and development in recent years, driven chiefly by central government subsidies, advantageous government policies and improved infrastructure. They offer higher standards of living, rising income and opportunities brought on by enterprises moving parts of their operations inland, and more flexible handling of the household registration policy—known as hukou in Chinese.

Under the hukou system, every Chinese person is registered according to their family’s place of birth and this impacts on many elements of a person’s life, including health, education and welfare services, as well as the right to live in and buy property elsewhere. It has historically been used by the government as a method of population management and it can be very difficult for people to change their hukou from a smaller city to a larger one, or from a rural to an urban area.

In practice, this means that migrant workers from inland areas who have been living in major cities such as Shenzhen and Shanghai may not be not entitled to public welfare services there—healthcare, unemployment benefits and education for their children—despite having worked and lived there for years or even decades.

To mitigate these difficulties and to encourage migrants to move to China’s smaller cities, China’s state planner in April directed local governments to lift hukou restrictions for second- and third-tier cities, making basic services in these cities accessible for newcomers.

Cities in Jiangsu Province such as Nanjing, Suzhou and Wuxi—all within an hour’s high-speed train ride from Shanghai—now report higher GDP per capita than China’s first-tier cities, each more than $18,000. But property prices in these cities are much more affordable than in first-tier cities.

“Most of our first time [home] buyers are from outside of Wuxi,” says Lucy Chen, an estate agent at Zhongshan Real Estate Group in Wuxi. “They’re moving to Wuxi for employment opportunities and a better education for the children.” Wuxi makes more sense than Shanghai for a number of reasons, including housing prices. “I’d say an apartment in central Shanghai is easily triple the price of an apartment in Wuxi,” says Chen.

Many young people are also choosing to remain in their smaller hometowns instead of moving to the nation’s megacities. “Some of my friends stayed in Yiyang because both they and their parents think that finding a stable job and remaining closer to home is ideal,” says Zoe Sun, a 23-year-old originally from Yiyang, a fourth-tier city in Hunan Province. “New companies and factories have recently opened up in Yiyang, providing more opportunities for employment. There are also plans for a high-speed railway station to be built there in the future.”

Ming Lu, an Economics Professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University explains that there are two forces at play, both of which are driving migrants back to smaller cities.

“The movement of people is driven by policy,” says Lu. “The central government is doing two things, one, controlling the population growth of large cities like Beijing and Shanghai using the hukou system and restricting land supply, and two, heavily subsidizing the hometowns of these potential migrants.”

“The first encourages migrant workers who may have been interested in, or already are living in China’s first-tier cities to move to smaller cities,” says Lu. “The second involves the ‘pulling’ of these migrants back to their hometowns or to other smaller cities.”

“Central government has been investing heavily in the infrastructural and real estate development of these smaller cities, subsidizing industries such as agriculture in the hopes of drawing the masses.”

The Winners

Those that benefit from these trends are the residents of smaller cities as well as companies that have taken advantage of the opportunities that smaller cities have come to provide.

In the past, many enterprises focused their business on first- and second-tier cities, but third- and fourth-tier cities are now also emerging as pillars of consumption. Much like Pinduoduo, other enterprises have also caught onto the potential for growth in smaller cities, with many Fortune 500 companies having opted to transfer parts of their operations to China’s inland cities. With lower costs, local government incentives, housing subsidies and a growing number of consumers in those areas, it appears to be a natural choice.

Last year saw both DHL and Lufthansa Cargo move portions of their operations to the city of Chengdu, while China’s top tech companies—Tencent, Alibaba and Baidu—have sought partnerships in inland cities to develop their AI initiatives, citing the benefits of lower tax and cheaper labor.

“Some companies are looking at first-tier cities and thinking that they are too expensive to hire employees at the salaries they’re able to offer and that smaller cities could give these employees a more reasonable standard of living for the salary they can provide,” says MacDonald.

Many small business owners also prefer setting up shop in smaller cities. “The pace of life in smaller cities is relatively slow while the quality of life offered here is quite high,” says Wu Kai, a small business owner in third-tier Rui’an in Zhejiang Province. “For entrepreneurs, third- and fourth-tier cities offer lower costs and a less competitive environment.”

Lower living costs in smaller cities allow their residents to have a greater amount of disposable income, which increases consumption rates. The rising level of income in lower-tier cities also means a change in consumption habits, with certain sectors seeing huge growth, particularly luxury goods, entertainment and tourism.

Those living in lower-tier cities also tend to have less debt, especially when it comes to home loans, allowing them to spend more. Official data showed that growth in sales of consumer goods last year eased back to 2.7% in Beijing and 7.9% in Shanghai, but generally less developed provinces such as Shaanxi, Yunnan and Anhui saw a growth of 10% or higher.

“Consumers in smaller cities now spend about 70 to 75% of their annual disposable income,” said Chinese investment firm Five Star’s strategic development general manager Frank Hu. “This is compared with 60 to 65% in tier-one and two cities.”

The China Tourism Academy revealed in 2017 that interest in trips abroad in lower-tiered cities was increasing dramatically, while travel company TripAdvisor said that interest in Chinese travel to Thailand is now driven by second-tiers cities as opposed to the expected first-tier ones.

Running risks

Despite the optimistic outlook that lower-tier cities may provide, there are still some key risks that need to be taken into consideration, including possible policy curbs on household leverage build-up, a housing market correction, the accumulation of local municipal debt, risks of private investment falling and a rise in US—China trade frictions.

MacDonald points out that “Smaller cities may have higher growth rates, but the actual additional value contributed to the Chinese economy is still heavily weighted towards the bigger cities, because they’re working from a larger base. So even though the bigger cities only report a 5-6% growth, they contribute more to the national economy than the 7-8% growth of a smaller city.”

The effect that the current national economic downturn may have on investment into smaller cities, particularly in infrastructural development and industry subsidies, could be huge as many of these smaller cities still rely heavily on funding from the central government.

To keep up with expectations, smaller cities also have to adapt to the demands of its newcomers. Common issues raised have been a lack of entrepreneurship support, still too few opportunities for employment and the need for higher salaries, particularly for recent graduates, and as Lu highlights, “Without jobs, people cannot move.”

There are two schools of thought on how the growth of smaller cities is going to play out. One is that consumption in inland areas may be able to act as a buffer against the economic slowdown that China is experiencing, while the other is that the growth of lower-tiered cities is to some extent artificial and therefore not necessarily sustainable. But regardless of how it plays out, the massive consumption potential of lower-tier cities could mean bright prospects for a range of consumer-focused industries, with implications for the overall Chinese economy and global investors.

“Of course, more than a decade ago no one would have thought that the speed of development would be so fast,” says Wu.

Others, however, say it is unlikely that stronger growth in smaller cities can meaningfully offset a nationwide slowdown.

“I do not have a very optimistic forecast for the growth of lower-tiered cities in the future, because if you look at the economic growth pattern of those smaller cities, you will see that their growth is mainly driven by very heavy investment,” says Lu.

“Many of their financial resources are transferred from the central government, and their local financial vehicles. They’re taking out bonds and loans from the bank, but the return on those investments are actually very low. So I don’t think the high growth in the past driven by investments can be sustained into the future.”