China’s online sector is witnessing a series of frenzied mergers, acquisitions and partnerships between sworn rivals. What is fueling this trend?

In the world of business, there are no permanent friends and no permanent enemies. Interest reigns supreme. Nowhere is this more apparent than in China’s internet sector. The year 2015 saw many unlikely mergers and partnerships between sworn enemies in different areas such as taxi hailing apps, online travel, group buying and classified advertisement websites.

Data collected by Dealogic shows that in the end of November 2015, China ranked first in the Asia-Pacific region with M&A deals totaling $497 billion, up by 69% year-on-year. Technology is the hottest sector and volume for tech M&As reached $153 billion, double the figure in the same period in 2014 ($75.8 billion).

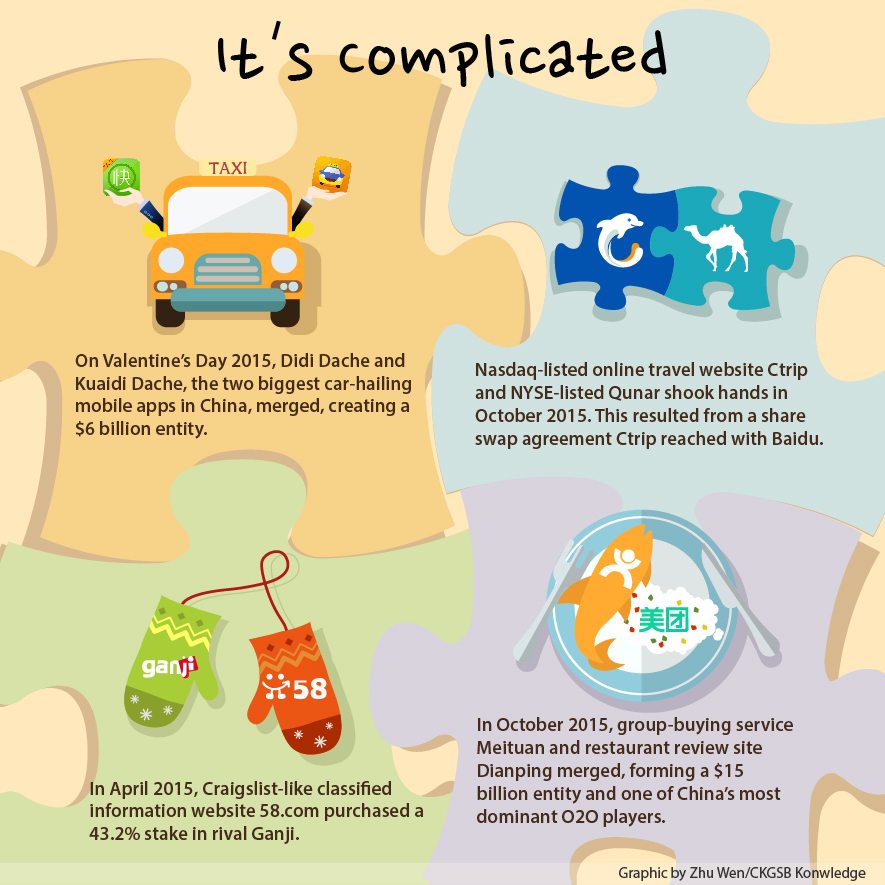

On Valentine’s Day in 2015 everyone was shocked when two sworn rivals—taxi-hailing apps Tencent-backed Didi Dache and Alibaba-backed Kuaidi Dache—decided to merge. The two had a bitter rivalry. They were engaged in a fierce price war in 2014, with each party burning cash in a bid to outdo the other and grab more customers. According to multiple sources, Didi and Kuaidi altogether splashed over RMB 2 billion (approx. $376 million) on subsidizing customer ride fares. Post-merger the two together control 83% of the private car-hailing app market in China.

Similarly in April 2015, the New York Stock Exchange-listed Craigslist-like classified advertisement site 58.com picked up a 43% stake in its old enemy Ganji. Data from multiple sources suggests that post this deal, 58.com and Ganji cornered over 70% of China’s online classified information market.

More recently, there was a merger between the Tencent-backed Dianping, which is often called China’s Yelp, and Alibaba-backed group buying website Meituan, a move that would further enhance their already solid foothold in the online-to-offline (O2O) market. This is the second time that Tencent and Alibaba have decided to work with each other after Didi and Kuaidi’s merger. However, things seem to have changed as Alibaba is now in talks to sell the 7% stake it holds in Meituan-Dianping in order to develop its own O2O platform, Koubei.

And in the online travel space, two of China’s largest travel websites, Ctrip and Qunar, found themselves in an interesting situation. On October 26th 2015, Ctrip confirmed its share swap agreement with search engine giant Baidu which held Qunar’s stocks. After the share swap, Ctrip now holds 45% of Qunar’s shares. James Liang, Founder of Ctrip, told the media that Ctrip will try its best to minimize talent loss and other instabilities that come in the wake of this transition.

Does It Make Sense?

So what is really fuelling this merger mania? How do two rivals who can’t see eye to eye suddenly decide to work together? Is there a method to this madness?

“One of the simplest ways to put it is that they can’t afford to burn cash anymore. Competing with each other ended up wasting a lot of investor money. Embracing each other seems more practical,” explains Arthur Zhang, Vice President at ZhenFund, an angel investment fund.

One of the newest buzzwords in China’s internet business is “capital winter”, a term coined to indicate the fact that less hot money is flowing in the market. Data from China Venture indicates that VC/PE activities during the second quarter of 2015 in China’s internet industry amounted to $3.78 billion, a fall of 50.36% compared to the first quarter. “Some money-losing projects, though large, find it hard to get investment these days,” says Will Tao, a China internet expert with extensive experience in the industry.

“Investors are more prudent at the moment, but still very active,” says Zhijia Xing, Vice President of ExaByte Capital, IDG Capital Partners. “Given that the economy did not perform as well as expected in the second half of the year, companies, especially the ones with great potential, are now more willing to talk.”

Competition is also indirectly fuelling the merger trend. According to Will Tao, “We often find more than five similar companies competing in the same industry.” He has a point. The success of some internet companies in China has spurred the rise of many me-toos. Take the food-delivery business where we are increasingly seeing more of the same kind of company with little or no differentiation. The question then becomes: how long before consolidation starts happening in the industry? Instead of indulging in a high-stakes competition with no surety of a reward, sometimes it makes more sense to work together. Taking Ctrip and Qunar’s case for example, Xing of ExaByte Capital, IDG Capital Partners, says, “Ctrip and Qunar, these two are too similar. Their tie-up at the core is about buying a competition out of the game.”

If you look deeper, you’ll see that many of the merged companies are somehow connected to BAT (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent). Didi and Kuaidi were heavily funded by Tencent and Alibaba respectively. Dianping received investments from Tencent. Baidu, on the other hand, was an investor in Qunar and post the share swap it now owns 25% of Ctrip. “BAT has played a crucial role in the mergers,” says Li Xiaoyang, Assistant Professor of Economics and Finance at CKGSB. “First of all, they have the money and money plays a big part. Second, they can drive the traffic.” There is an indirect connection too. “You can deem it as BAT extending their portfolio in this round of the internet heat wave,” says Zhang from ZhenFund.

Sailing the New Ship

When two rivals decide to join hands, it creates some synergies and some potential minefields. Often, the two companies have inherently different cultures, different work styles and possibly also a different understanding of who should be in the driver’s seat. This sets up the right conditions for friction and clashes.

In almost all the companies involved in the cases mentioned above, the founders still have a very strong voice in the actual operations. For someone who has worked very hard to build a company out of nothing, it is not easy to take the backseat. Understandably, the battle for who will sit in the driver’s seat is fierce. “In the actual operation of the newly formed company, one party will inevitably take the lead… This is bound to happen. The whole M&A process is intertwined with personnel adjustments,” says Zhang from ZhenFund.

Therefore, in order to achieve a relatively smooth transition, Didi and Kuaidi adopted the co-CEO model for the new company, where Didi’s Founder Cheng Wei and Kuaidi’s Founder Lv Chuanwei both serve as CEOs in the new company. Yet it is rumored that in reality it is Didi’s founder who has the upper hand. “[The] Co-CEO [system] is a temporary solution. Co-CEOs, especially [when we are talking of] ex-rivals, won’t last long. The competition will only disappear when one party is ruled out completely,” says Will Tao.

When Meituan and Dianping decided to merger, they claimed that the new company will adopt the co-CEO approach. But only one month later, Founder and CEO of Dianping, Zhang Tao, was assigned as the Chairman of the board and Meituan’s former CEO Wang Xing continued to serve as the CEO. At that time, almost everyone thought the new appointment signaled that Dianping was being ousted from the game. Zhang Tao, burst into tears at his farewell party.

The co-CEO strategy was also adopted in the 58.com and Ganji case. However, in November 2015, Ganji’s Founder and CEO Yang Haoyong stepped down from the new company’s management team and became CEO of second-hand vehicle trading platform Guazi.

Li from CKGSB says that one party will eventually have to give in, and that could either be in the form of managerial control or shareholding in order to keep the chaos at the minimal level.

The new company may also have to deal with another headache: the decision to keep both brands or just one. Some, like Didi and Kuaidi, keep both the brands. That can sometimes be a good strategy when both brands have their own loyal customers. But sometimes it may backfire as the two brands—now from the same stable—are still competing with each other. Sometimes it does make complete sense to maintain the individuality of both brands. For instance, in the Meituan and Dianping case, the two websites will continue to operate independently but with a different focus. Dianping is set to shift more towards low frequency and pricier services like wedding planning and exhibitions, while Meituan will lean more on higher frequency services such as food delivery. Similarly, Ganji is expected to reinforce its influence in second-hand car trading and recruitment, while 58.com will continue to develop the property leasing and O2O market markets which it is already good at. The difference in focus will minimize the possibility of them undercutting each other.

New Disruptors

When Didi Dache and Kuaidi Dache merged they ended up creating a $6 billion behemoth. When Meituan and Dianping merged, it created a $15 billion entity, one of the biggest players in China’s O2O industry.

According to data from Analysys, a research company, Ctrip and Qunar commanded 38% and 30% of China’s online travel market respectively in the second quarter 2015, ranking number one and two. In Didi and Kuaidi’s case, the two entities combined control over 83% of China’s car-hailing market, leaving Uber in second place with just 14.9%. Such monopolies make it hard for smaller start-ups to survive.

“In the US, some business actions are prohibited by law [if they create monopolies], however in China many actions are merely regarded as business maneuvers,” says Zhang from ZhenFund. On the other hand, he adds that “monopolies can actually boost productivity in some industries. If there is too much competition [from smaller companies] in the market, it will give rise to a lot of friction within the market.”

The creation of one entity out of two erstwhile rivals can have a positive rub-off too. “Taking Didi and Kuaidi’s merger as an example, the newly formed company will have more market power. They could shift their focus from competing to innovating,” explains CKGSB’s Li.

Xing from ExaByte Capital holds a different opinion. He believes that the word “monopoly” should not be used to describe the internet world at all. “The best thing about the internet is that it has fair competition. [The internet industry in China] has almost no government interference.”

Regardless of the hardships, smaller enterprises still have a chance to prosper in the business by finding a niche market or owning a core technology that no one else can replicate. “They need to find their [competitive advantage], rather than relying on BAT’s traffic or financial support,” says CKGSB’s Li.

The threshold of monetizing the Internet is quite low and as a result, the industry has become extremely crowded. But slowly, the situation is changing. As VCs become more prudent about where to invest, China’s internet industry will have a healthier and more sustainable environment for good businesses to flourish. “So I think smaller enterprises still have a chance,” says Will Tao.

The future of China’s internet market is hard to predict as everything changes so fast here, but it is estimated that more such mergers are likely in the foreseeable future. Industries such as food delivery, online video streaming and P2P (peer-to-peer) lending are expected to witness more consolidation. But once they take the plunge, companies should be smart about managing the transition else they’ll end up destroying more value than they have created.