The demand for wine among Chinese consumers is growing, creating an opportunity for wineries in the country as people look beyond imports

A stone chateau sits on a slope surrounded by sprawling vineyards complete with a wine factory and cellar, welcoming visitors for wine tastings while grapes are hand-picked and sorted under broad blue skies.

This may sound like a scene straight out of a famous wine-making region such as Tuscany, but Treaty Port Vineyards is in fact near the seaside town of Penglai on the eastern Shandong peninsula.

“I first started working in China in the 1980s and the local wines were terrible!” says Yorkshireman Chris Ruffle, owner of the winery. “This was one incentive in setting up Treaty Port Vineyards and planting our own vineyard in 2005.”

A thirst for wine

China has been producing alcohol since the dawn of civilization and is well-known for its formidable clear grain alcohol known as baijiu, but it is only fairly recently—in the past two decades—that the country has become a contender in the global wine industry. The modern trend in drinking grape wines started in the 1990s with the consumption of imported red wines being a major status symbol. Red wine was later also enjoyed at special occasions and official banquets, with its popularity enhanced by its alleged health benefits. Drinking a glass or two of wine has now become, for an increasing number of Chinese people, an ordinary part of dining out.

Over recent years, the number of wine drinkers has soared, making the country the fifth largest grape wine market in the world by total consumption, and the biggest in the world by red wine consumption, according to a report released by financial data provider MarketWatch. With the country’s growing thirst, the China Wine Competition, an annual international event held in Shanghai, estimates that consumption will rise over the next five years by over a third.

The amount of wine imported reached 729.68 million liters in 2018, an increase of around 80% when compared to 2013. France is the largest source of wine imports and leads the market with a 14% share, but French vineyards are seeing their share decline as other countries build their presence. The popularity of Australian wines is still growing, and they take a 9% market share—up from just 4% in 2016—driven by strong Australian brands such as Yellow Tail, Penfolds and Rawson’s Retreat, says Beverage Daily, a news and analysis firm of the beverage industry. Chilean wine takes third place with a 6% market share. The value of wine imports from France in 2018 was about $1 billion, Australia $723 million and Chile $270 million.

“In the 1980s almost all wine was imported,” says Ruffle. “But the potential [for domestic wine] is clearly massive given the scale of the market and the low penetration rate of wine in China.”

Imported wines now account for only about 40% of the wine market, reported Beverage Daily, meaning that most of the wine that is consumed today is produced domestically.

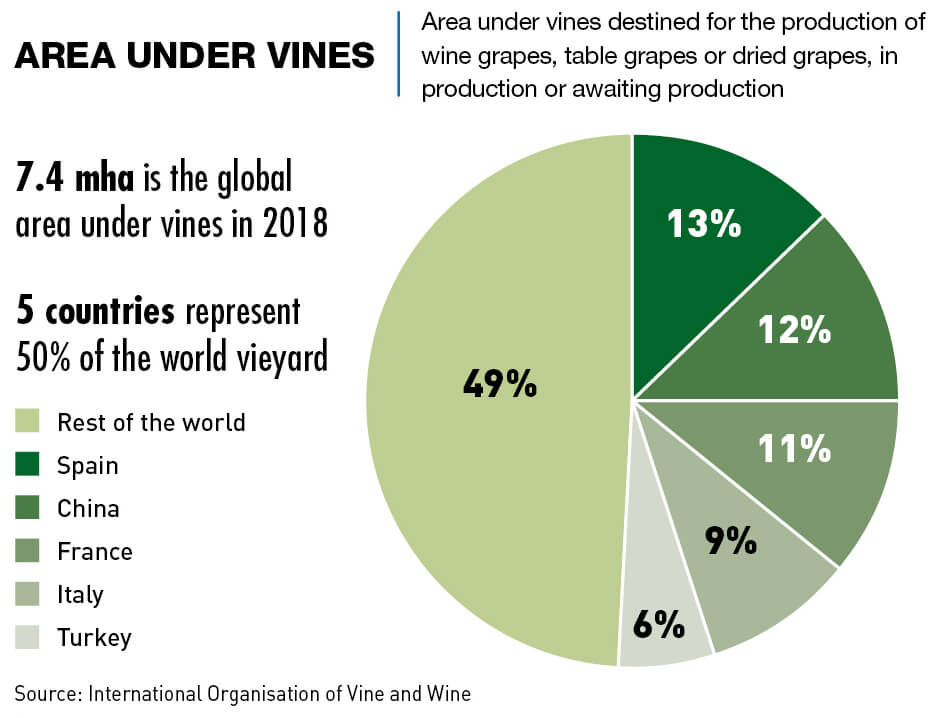

The growth of the domestic wine industry has been impressive, with several wineries now producing internationally-recognized wines. China produced over 900 million liters of wine in 2018 and has the second-largest vineyard area globally. Some of the best-selling names in the industry include Changyu Pioneer Wine, Dynasty Wine, Great Wall Wine and Ningxia Silver Heights Winery.

“Many wines sold in China are still imported, but as the market and domestic production matures, Chinese wines will have the opportunity to become part of mainstream wine consumption,” says Andy Xu, owner of Cellar Door Wines in Shanghai, an importer of Australian wines.

Suvania Naiker, owner of The Cellar, an importer of South African wines, highlights how there are now significantly cheaper options available to consumers, which also contributes to higher levels of consumption.

“Wine is priced very affordably in China, making it highly accessible,” says Naiker. “The cheapest locally produced wine I’ve seen comes in at around RMB 20 ($2.80) per bottle. Imported wines are more expensive, typically from around RMB 50 and up.”

The terroir

The most popular domestically produced wine regions tend to be in northern China, with the exception of Yunnan province, which is in the south. A report released by the International Bulk Wine and Spirits Show (IBWSS), an exhibition trade show in China, highlights Ningxia as having attracted the most attention from Chinese winemakers looking to expand. Located nearly 1,500 kilometers west of Beijing, it has a cool, dry, semi-desert climate and the report compares it to the sunnier Bordeaux region in France.

Yantai in Shandong province is also an admired wine-making location and is home to over 140 wineries, with 40% of all Chinese wine being made in the region. Decanter China, a leading wine media brand delivering China-related wine news, also identifies Xinjiang region as promising, as well as Yunnan province and the Loess Plateau in Shanxi province to the south of Ningxia.

“There is no perfect place to make wine in China,” says Ruffle. “My area, Shandong, often has problems with rain in August, so we develop strategies to cope with this and avoid thin-skinned grapes. In our main ‘rival’ Ningxia, the summer is hot, and there are few insect issues, but the vines need irrigation in summer and the winter is very cold, and all the vines need to be buried, which is labor-intensive.”

Red, red rosé

When speaking about wine in China, it is important to highlight how red wine dominates the market, particularly cabernet sauvignon, which accounts for 76.5% of domestic production, and merlot, which accounts for 12%, according to the IBWSS.

In the early stages of the wine boom, Bordeaux’s influence on the industry was huge, with many Bordeaux chateaux now having been bought by Chinese entrepreneurs. Varietal selection, winemaking techniques and even winery design have mirrored the famed French wine region, contributing toward the great interest amongst Chinese drinkers in cabernet.

Not surprisingly, local producers have also looked for ways to make use of this red wine trend. One interesting development has been the rise of marselan—a French cross of cabernet sauvignon and grenache vines—as the “signature grape” of China. Marselan appears to be on its way to become the most important Chinese grape, surpassing even cabernet sauvignon.

Apart from the status attached to it, as well as the rich flavors, red wine is also preferred by Chinese tipplers for health reasons.

“Wine is perceived as healthy, especially red wine,” says Ruffle. “And of course, relative to drinking baijiu, it certainly is! The color red is also considered auspicious, particularly amongst older generations.”

Aficionados also argue that red wine pairs better with Chinese cuisine, but while the dominance of red wine is undisputed, consumers’ knowledge about wine and tastes are a changing.

“There used to be a great deal of misunderstanding when it comes to white wine,” says Sun Zhiyong, a restaurant owner in Zhejiang province’s Wenzhou city. “Brand promotion was not done well, and the taste of Chinese food is generally heavier, so red wine tends to complement the food better.”

“More and more people are interested in trying white wines and even dessert wines,” says Naiker. “With Chinese interest in the wine scene being relatively new, consumers’ tastes need time to develop. In the north, there has actually been a large increase in sales of dessert wines, such as prosecco, moscato and rosé blends because of the way it is now marketed as a complement to food.”

Vinification

In terms of demographics, wine consumers are mostly younger urban residents, particularly in the country’s biggest cities— Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai—who view wine consumption as being international and fashionable.

“It’s definitely the young working professionals driving this trend of wine consumption,” says Naiker. “Previously it was an older demographic that enjoyed wine, but when more variants were imported and not just red, the younger generation started taking more of an interest. Chinese people have also been consuming more and more wine because it has made them feel like part of a global community.”

“Drinking wine is trendy,” says Xu. “Most young people will start with a sweeter variety, and as their palates develop, they become more adventurous and willing to try other kinds.”

Domestically produced wines are increasingly dominating the market but there are several factors that stand in the industry’s way, including high production costs, restrictive government policies and the limited scale of wineries.

“The wine industry still has a long way to go,” says Xu. “In countries like Australia, it’s not necessary for boutique wineries to have their own bottling facilities. They can rent bottling machinery by the day. Here, bottling equipment is a prerequisite before the government grants you a license to produce wine, which is a big challenge for the growth of Chinese wine.”

“Being able to produce wine therefore requires a huge level of investment,” adds Xu. “It’s changing, albeit very slowly, because it’s not good for business. The government can’t relax all of these regulations at once, because then it would be difficult to maintain standards.”

Currently there is next to no export of Chinese wines, but Naiker believes that there is potential for it to become a global contender in the future.

“Once issues involving branding, mechanized production and scale are resolved, then Chinese wines have a vast potential for growth,” says Naiker. “I predict that Chinese wine has around eight to 10 years to go before it becomes known on the world stage and there is a demand for it in other countries.”

There is also the question of how the “Made in China” label would affect sales abroad.

“There is a big credibility issue: ‘Wine from China?!’ So, we need to price competitively to get consumers to try our wine,” says Ruffle. “When they try it, the reaction is usually positive. My main aim is the break into the Chinese restaurant sector abroad, which at the moment largely misses out on the wine margin.”

“Chinese wines have huge potential,” says Naiker. “It needs to focus on its home base, as consumption here is massive. Interest abroad will take a longer time to grow, but it will surely follow.”

Fermentation

With the improvement of living standards and changing lifestyle choices, the demand for wine is continuing to increase. When visiting a vineyard in Ningxia in mid-June, President Xi Jinping said that the wine industry has promising prospects as the living standards of Chinese people continue to rise.

“The potential is clearly massive given the scale of the market and the low penetration rate,” says Ruffle. “However, there is also a big job of education to do when it comes to wine culture. More work needs to be done on food matching, given the variety of foods and tastes at a Chinese feast.”

“There are definitely opportunities for investors, but profit is not quick to make,” says Xu. “To produce good wine requires many years of trial and error. It needs to be viewed as a long-term investment.”