As the Chinese property market slows and complicates the country’s economic outlook, the government faces a tricky balancing act.

The Chinese property market, long identified as one of the key fault lines in the countryʼs economy, has moved into one of its most testing phases yet. Eight out of 10 economists surveyed by CNNMoney in July named the real estate sector as the area posing the biggest risk to Chinaʼs slowing economy, and analysts and investors who subscribe to this negative view include Nomura, UBS and George Soros.

The importance of real estate to the Chinese economy is not in dispute, nor is the existence of bubble traces, at least in some parts of the country. The only uncertainty comes over the scale of the problem and how the Chinese government will handle it.

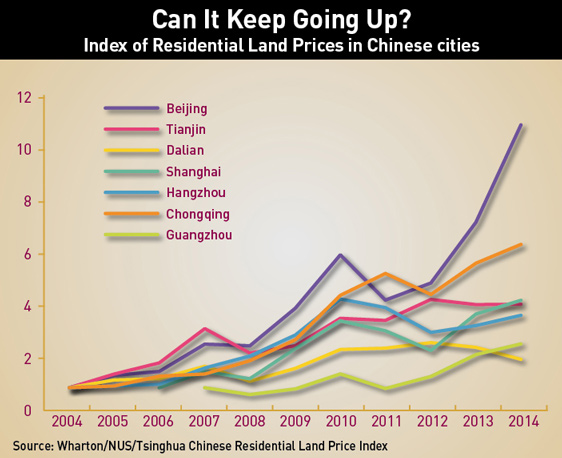

A string of developments in 2014—but set into motion years earlier—have highlighted the growing need for some sort of controlled adjustment. With cash flooding into the property market thanks to a massive 2008 stimulus, and for want of better investment options available to investors of every stripe in China, the governmentʼs attempts at market adjustment have in turn discouraged, then encouraged prices to balloon as local governments got cold feet.

Measures since then have helped mitigate the damage in the short-term, but in light of the problems spawned by the 2008 stimulus—among them the very property bubble being dealt with now—another broad stimulus is no longer an option in the eyes of top leaders. With stability on the line and pieces of the policy puzzle now falling into place, the governmentʼs intention to play a more active role in coaching the market to a more sustainable state is starting to come into view.

Brought to the Boil

Chinaʼs property bubble can be traced back to the global financial crisis in 2008, although prices had been rising solidly for years before that, says Shengxian Qin, Deputy Research Director for J Capital Research, a Beijing-based firm. China largely escaped the impact of the 2008 crisis by pumping a RMB 4 trillion ($585 billion) financial stimulus package into the economy, which included loosened lending conditions and lowered interest rates. By early 2009, property sales and prices were skyrocketing.

This put further pressure on ordinary Chinese, for whom property now serves as a storehouse of value. Beijing resident Florence Fu, 40, owns two apartments. Her family lives in one, and the other they rent out. She and her husband bought the second apartment 10 years ago, when she says it was much cheaper than it is now. Like most middle-class Chinese then, they bought it as an investment. “Because of inflation, there are no other ways to make your money grow,” Fu says. “If you invest in property, you can also get income [from rent].”

Societal pressures also play a role in new home purchases. Parents try to support their children until marriage, especially sons. A house or apartment is one of the three unofficial requirements for a bachelor to be considered marriage material.

Cao Loubin, 47, is another Beijing resident with two apartments, but is saving up to purchase another one. “I need to prepare it for my childrenʼs future use,” he says. “If I donʼt buy it now, when the children grow up, property prices may be too expensive to buy.” Like Fu, he believes his investment will only grow as property prices in the city rise. Fu likewise plans on eventually passing her second apartment down to her son, now aged 10.

Buyers were not alone in thinking housing prices would indefinitely rise— many property developers assumed the same. However, the ones who jumped on the bandwagon too late, especially in cities with more sluggish demand, caused a surge in excess properties throughout the country.

While the infrastructure-building boom that resulted from the stimulus had many positive effects, the lowering of restrictions on loans also led to many risky business decisions, especially in the real estate development sector. China has a paucity of investment outlets, pushing people towards the only viable investment vehicle: property. “Their stimulus actually helped finance property developers and made people buy more,” says Qin.

Home sales rose at an average rate of around 30% each year from 1998 to 2009, according to Centaline, the countryʼs biggest real estate brokerage, before slowing to about 10% from 2010. They briefly flattened in 2012 due to government policies that sought to control bubble tendencies, but took off again in 2013 when the policies were relaxed.

Further signs that Chinaʼs property sector could be forming a bubble came when it was revealed by Chinaʼs National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) that in 2013, the value of new home sales rose 27% to RMB 6.8 trillion ($1.1 trillion) from 2012.

Headlines of “Chinaʼs Ghost Cities” were continuously replayed in the media alongside images of empty, immaculate developments without a single person in sight. Abandoned, half-constructed residential and commercial units were also a common sight, as demand suddenly dropped.

The weak sales, oversupply of units and falling demand were all unhealthy signs that a bubble had developed in the Chinese property market.

Action and Reaction

In an attempt to stave off the growing property bubble, local and regional governments, one by one, began implementing purchase caps. The caps differed slightly from city to city, but their purpose was the same: bring an increasingly unruly drive upward in property prices under control.

As these purchase caps were being implemented, a nationwide campaign headed by President Xi Jinping was rolled out to eradicate corruption, with the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) at the helm. The corruption crackdown affected the property sector as many officials had accepted houses as bribes, although exact numbers are hard to come by.

Heads began to roll and those fearing NDRC scrutiny not only ceased buying properties, particularly luxury units, but also began offloading them at heavily discounted rates. And to make matters worse for luxury developers, a Barclaysʼ survey in September of individuals with $1.5 million or more in net worth found that 47% of Chinese respondents want to move to another country in the next five years. These two things combined to put a dent in real estateʼs most profitable sector.

By May 2014, housing prices in half of the 70 cities monitored by the NBS registered decreases. This was the most they had fallen since May 2012 when the government first tried to rein in the growing property bubble.

With signs that efforts to control the bubble had actually been too successful, local governments quietly or openly began discarding purchase restrictions. In early August, 32 out of 46 regional governments relaxed or scrapped limits on the number of properties a person could own, according to Caixin magazine. By late October, Bloomberg reported that only five cities had the restrictions in place.

Housing prices had continued to fall, with Augustʼs figures showing the lowest drop since the NBS changed its calculating method in January 2011. Sixty-eight cities registered a drop in property prices that month, down 1.1% from the month before, after dipping 0.9% in July, according to Reutersʼ calculations based on the NBS figures. The next month, all but one of the 70 cities monitored by the NBS registered a drop in property prices.

Home sales fell 11% the first nine months of 2014, as per Bloombergʼs calculations based on the NBS numbers. Additionally, the China Land Surveying and Planning Institute reported slowing growth in residential land prices for July-September, the third consecutive quarter that this had happened.

The runaway growth in prices had been successfully contained, but the change had been too quick for the government and investors to be comfortable.

Old Problem, New Measures

Investorsʼ fears of an uncontrolled crash were somewhat soothed when the Peopleʼs Bank of China (PBoC) distributed RMB 500 billion ($81 billion) to the countryʼs top five banks in the same week that the low August NBS figures were announced.

The national Golden Week holiday, annually celebrated from October 1-7, typically results in a cash crunch due to an uptick in consumer spending at this time of the year. Some analysts speculated that the RMB 500 billion stimulus was for liquidity issues that would arise with the holiday, but because giving RMB 100 billion to each of the banks was large enough to lower the banksʼ reserve ratio by 0.5%, easing pressure on mortgage lending, others thought that it might well be connected to the countryʼs ailing real estate industry.

“Basically this is a small stimulus,” says Liu Jing, an accounting and finance professor at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. “There are lots of uncertainties. And under the situation where there are lots of uncertainties, people donʼt invest,” he says. “When this happens, the government needs to stimulate a little bit and itʼs been doing it for a while.”

Lending further weight to this view, on the eve of Golden Week the PBoC and the China Banking Regulatory Commission issued a statement allowing banks to lower mortgage lending rates to people buying second or third properties. This was the first time property restrictions had been loosened since 2008. It was becoming clearer that the government was taking steps to address the deflating bubble.

Previously, the government had been taking steps to cool an overheated property market, with loan conditions for those looking to buy a second or third piece of property being made more onerous to discourage borrowers. The statement now allowed second property buyers a 30% discount on their mortgage rates—previously only available to first-time buyers. Down payment levels were also cut more than half to 30%, and restrictions for third-time property buyers were similarly loosened.

These actions were enough to see a small rally. Poly Real Estate, one of Chinaʼs top five developers, reported that their sales from October 1 to 7 reached RMB 7 billion ($1.14 billion). Stock indices of both Poly and Vanke, Chinaʼs top real estate developer, surged at least 2.8% the week. However, analysts predicted the gains would be short-lived. True enough, Polyʼs stock fell the succeeding week by 2.1%.

Complications: Numerous

In part, this is because the policies are not sustainable, according to Qin. “I donʼt think this will prompt too much demand to purchase properties. There will still be a large amount of inventory in the market.”

“Our checks show that inventory in some low-tier cities is already higher than the actual population,” says Qin. “We interviewed many people in lower-tier cities and most people have more than one unit. Some have 2-3 units.” The danger lies in there being little or no migration into those cities to absorb the surplus.

The effect a housing bubble has on wealth is further reason to correct it. “The housing bubble generates a substantial degree of resource misallocation and welfare losses, prolonging economic transition and slowing aggregate economic growth,” said a working paper by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis titled ʻThe Great Housing Boom of Chinaʼ. The authors of the paper, Kaiji Chen and Yi Wen wrote: “Such welfare consequences offer an additional explanation for the Chinese governmentʼs concerns over the great housing boom and its policies to contain the bubble.”

“Housing investment is one of the largest investments people have in China,” says Liu. “If the price [of land] goes down, you can wipe out so much wealth.”

However there are stark contrasts between market sentiment in first-tier cities and everywhere else according to Liu. “The higher end markets, for example, in larger cities, are still holding up quite well. But in second-tier, third-tier cities, I think that probably prices have gone up too much and are coming down fast,” he says.

Qin emphasizes that prices are falling because of excess supply. “The government wants to help developers de-stock their inventory,” she says, but some prices are stubbornly high. “The buyers cannot afford the market prices. Investment demand will be squeezed out in the long-term and short-term.”

Prices that are inflated and too high, like in the lower-tier cities, can distort the economy, according to Liu. An ideal situation would be the government letting the air out of the housing bubble slowly and in a carefully controlled way. “Maybe not too much,” he warns. “You donʼt want to have a crash situation, but it should go down or theyʼll have a bigger problem down the line. It is better to correct it now.”

In for a Long Landing

Strong signals have been coming from the government that it has learned a hard lesson from its 2008 borrowing binge. Premier Li Keqiangʼs speeches at the Summer Davos meeting and a Germany-China business forum in October shows that the government has come to grips with its slowing economy and understands that its previous investment and export-led growth model is not sustainable.

“This new leadership is very cautious. They acknowledge that the past stimulus has been excessive,” CKGSBʼs Liu Jing says. “In 2008, the stimulus was rolled out under a panicky situation. Thatʼs why theyʼre doing things very slowly,” he says, referring to the targeted stimuli.

Premier Li emphasized the need to get used to Chinaʼs “new normal”. For 2014, the country would target 7.5% growth, but Liu says it will be difficult to reach. The Chinese real estate market plays a large role in the countryʼs GDP, making up approximately 15% of it. According to a UBS calculation, every 10% drop in property investment is equivalent to a 2% drop in GDP growth.

Michael Pettis, Professor at Peking Universityʼs Guanghua Business School, explains on his personal website that it would be better if the government aims for a long (not hard) landing. This would involve controlled growth declining sharply but at reasonable rates like 3%, as opposed to a few years of still impressive growth at 6-7% followed by a hard landing.

Falling investment growth in real estate would cause unemployment to surge, he wrote in September post, because of its connection to about 40 separate industries. That would affect household income and consumption growth, representing a challenge to an orderly adjustment.

“Chinaʼs real estate sector is undergoing a major revamp,” writes Phei Chen Chin, CEO of Sino-Singapore Guangzhou Knowledge City Investment and Development Co., in an email interview. “It will eventually lead to healthier development in the future with moderate but more sustainable growth in line with Chinaʼs economic development.”

Despite uncertainties, it appears the government will continue playing an influential role in controlling the state of the property market, at least for the time being, and in late October the government declared its support for the market, although details werenʼt forthcoming. Property owners can breathe a little bit easier knowing it is in the governmentʼs best interest to avoid a disastrous property collapse.

According to Chin, the growing pains currently being felt are a bitter medicine that has to be swallowed today in order to guarantee a healthier property market tomorrow. “It will allow the government to reduce direct interference in the real estate market, giving more room for market forces to determine real estate development,” he says. “However, for the foreseeable future, the governmentʼs policy influence is still essential for maintenance of stability.”

The present may be shaky as the government irons out the countless wrinkles accumulated from longtime overuse of housing as a storehouse for value, and it may have a tough time weaning China off its real estate addiction in the short term. However, there seems to be little doubt that so long as stability comes first the authorities will step in when needed to ensure health of the market—and the country.