The focus of the BRI is shifting to projects aligned with China’s national strategic priorities

If you had attended the 2019 Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, there is a chance you could have bumped into one of seven different EU leaders. Just four years later, however, only Hungarian leader Viktor Orbán made the trip to the Chinese capital, and one of the seven countries, Italy, has left the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) altogether.

The October 2023 forum marked the 10th anniversary of the BRI, and in spite of the lack of attendance by some countries’ leaders, it marked the coming of age of the initiative, with new characteristics. At the forum, Chinese leader Xi Jinping made it clear that the focus will now be on more yuan-denominated, and what he termed as “small yet beautiful,” projects, as opposed to the monolithic infrastructure undertakings of the past.

Along with a greater focus on the Global South, these changes are set to a background of criticism of various parts of the initiative, such as financing. But what is clear is that the BRI is here to stay and it is providing a useful tool for China across the world, both economically and politically.

“The BRI is many things to many people,” says Dominic Chiu, Senior Analyst, China and Northeast Asia at Eurasia Group. “First and foremost, it is China’s global program to offer public goods to the world, especially to developing countries. But the Chinese government policy is also realistic, it also hopes to gain both economically and politically from the BRI.”

Showing initiative

China’s rapid economic expansion since the turn of the 21st Century is well documented, and integral to this has been the country’s massive infrastructure development. But by the early 2010s, domestic demand for infrastructure development was beginning to be outstripped by supply, and a new home was needed for some of this capacity. At the same time, the launch of the BRI in 2013 offered a chance at a greater political and economic role on the global stage.

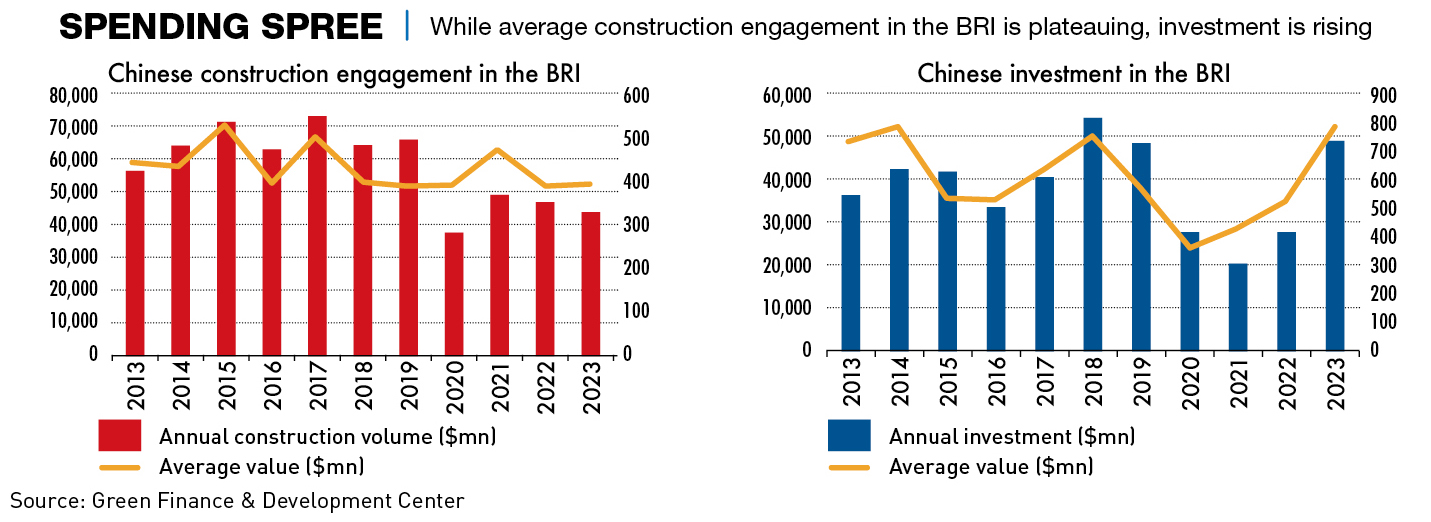

As of the end of 2023, more than 200 BRI cooperation agreements have been signed with over 150 countries and 30 international organizations, and, according to the China Belt and Road Initiative Investment Report, 2023 saw around $50 billion in BRI-related investment, the highest it has been since 2018. The decade mark also saw cumulative BRI engagement pass $1 trillion, with around a 60-40 split between construction contracts and non-financial investments.

In 2023, investment grew across most of the Global South, and a decrease in Latin America and the Caribbean does not indicate much in the way of future trends, as BRI investment into specific regions has regularly fluctuated throughout the initiative’s history. Overall there has been an upward trend in engagement since the last fall in 2019.

Projects have ranged from traditional infrastructure such as ports, roads, and railways, to digital advancement programs including telecommunications infrastructure, satellite television, and Wi-Fi. More recently, green technology and renewable energy projects have come to the fore. China’s energy-related engagement in 2023 was the greenest in absolute and relative terms of any period since the BRI’s inception, reaching $7.9 billion. The battery sector saw another $8 billion in engagement.

“China’s capacity in green technologies has expanded significantly, particularly over the last 10 years, and this has been reflected in the BRI,” says Christoph Nedopil Wang, Professor of Economics and director of the Griffith Asia Institute at Griffith University. “In the olden days you would have expected developed countries would benefit mostly from this, but there are actually a lot of emerging economies, particularly in Southeast Asia that have benefited from China’s green technology investment.”

Making headway

For a global initiative of such scale, the BRI can be considered a success by a number of metrics, and has met many of its original goals of helping deal with infrastructure overcapacity, providing value for both China and recipient countries, and helping build goodwill.

Market development has been a key benefit of the BRI, with projects playing a role in creating new markets for Chinese goods and services. The initial major infrastructure projects, such as roads, railways and ports, are now able to be used by other businesses, including a growing number of private enterprises, to enable increased trade.

“It’s not just a case of building the infrastructure, and then the infrastructure sits there,” says one European analyst. “It’s also that Chinese companies are often piggybacking on to this, meaning a lot of Chinese companies are now invested in parts of the world that they might not have been, had the infrastructure not been built in the first place.”

“Taking Africa as an example, China’s trade has gone through three stages,” says Tao Zhigang, Professor of Economics and Strategy at CKGSB. “The first was low-end business, selling clothes and the like. The second was the large SOEs coming in and doing the large infrastructure projects. Now that the infrastructure is ready, we’re seeing the third stage, and that is the involvement of larger businesses, including many private enterprises, approaching the markets as they would anywhere else and conducting much more profitable business.”

As a result, there are now a number of privately-owned Chinese companies that have been set up with non-domestic targets in mind, including Shenzhen-based mobile phone manufacturer TECNO Mobile. The company has no real presence in the China market but utilizes the country’s supply chain advantages by manufacturing most of its products domestically, before exporting them to the target markets for which they are specifically designed, most of them BRI participant countries.

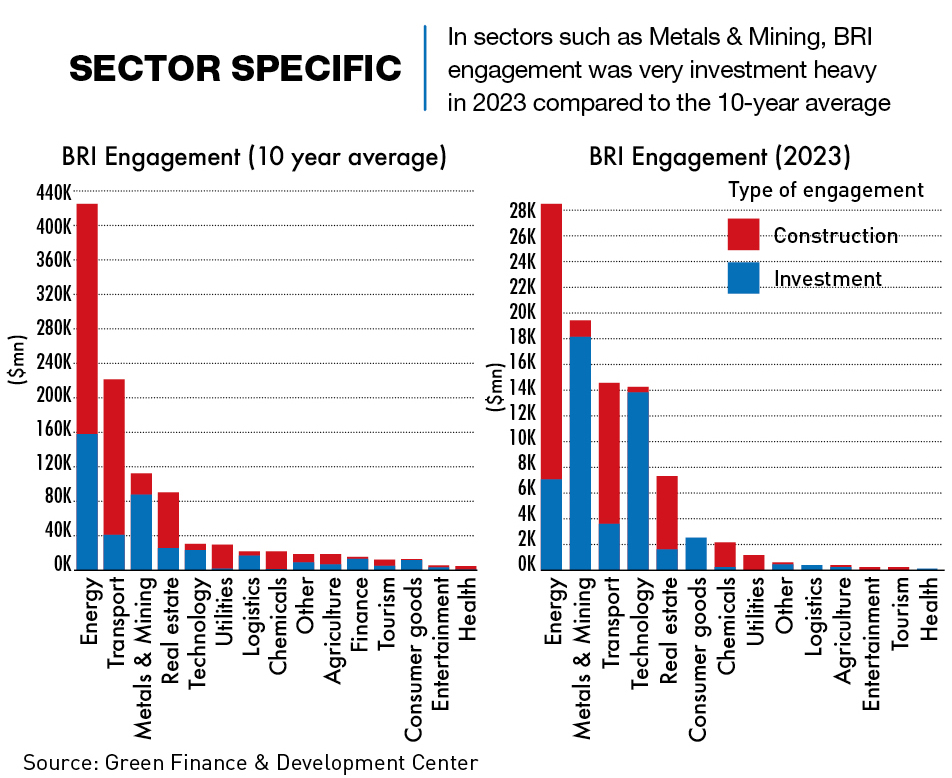

China has also gained access through the BRI to a wide range of resources to support its domestic supply chain, now with a particular focus on the green transition. Chinese engagement in metals and mining reached $19.4 billion in 2023, the highest level since 2013 and up 158% from 2022. Engagement is spread across Africa, Southeast Asia and Latin America, and is increasing in its verticality, with companies now engaging more in downstream activities in the source country on top of simple resource extraction.

“Securing resource access has been almost tangential to the BRI,” says Nedopil Wang. “It is driven by a desire to shore up the domestic supply chain, but the development of various infrastructure projects through the BRI has certainly helped the process.”

China has also gone some way to increase its soft power impact in many BRI countries. Soft power is difficult to quantify, but often the key balancing act for countries in terms of international allegiances lies between national security and the economy, and China isn’t necessarily aiming to claim pole position for both.

“The geopolitical ambition of the BRI and broader Chinese statecraft in a lot of the developing world is not so much trying to get countries onto China’s side, but it’s trying to get countries to a position of neutrality,” says the analyst. “The countries will often still view the US and institutions like NATO as a security provider, but China has very quickly become their primary economic partner.”

For recipient countries, there have been some benefits to participating in the BRI, including the aforementioned market development that has occurred at a speed and scale that would not have been possible without Chinese financing and expertise.

Tightening belts

While there have been positive outcomes from the BRI, for both China and the countries that have received BRI-related spending, the initiative has not been without its controversies. These range from small, project-related issues to larger concerns regarding China’s approach to deal-making or geopolitical impacts.

At a project level, there have been several criticisms of built infrastructure either being left incomplete or failing to meet specifications, and in some cases falling apart after only a short period of use.

China has also been accused of undertaking ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ by financing projects with a low level of commercial viability, something which the country has always denied. Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port is the most cited example, where the China Harbor Engineering Company built a port that many analysts argued lacked any real level of viability. Following an economic downturn in the country, Sri Lanka was forced to turn to the IMF for a bailout and the government needed a way to raise funds, for which the poorly-performing port was a prime candidate. Subsequently, a contract to operate the port for 99 years was secured by China Merchants Port Holdings.

“In Sri Lanka, the construction of ports and airports, financed by Chinese loans, became emblematic of the ‘debt-trap’ narrative, however, the complexity of the debt dynamics, including interest rates, repayment terms, and project viability, often obscured a clear understanding of the situation,” says Yasiru Ranaraja, Founding Director of education and consulting platform Belt and Road Initiative Sri Lanka. “Many challenges can be addressed more effectively with improved transparency and communication throughout the project lifecycle.”

Hambantota is not the only example, and the specter of unpayable debt now hovers over a number of BRI countries. According to a 2023 report by the research institute AidData, which tracks development finance, China is now owed around $1 trillion, similar to their total outlay, with 80% of that debt being held by countries classed as being in financial distress.

By the end of 2021—the most recent data available in the report—Russia, the largest recipient of BRI funding, owed $169.3 billion, the most of any country. And given that these figures were prior to the war in Ukraine, it is very likely that the number is now much higher. Other major debtors are Venezuela, owing $112.8 billion, Pakistan, with $68.9 billion in debt and Angola, which owes $64.8 billion.

“The debt issue is increasingly becoming a challenge that China is facing, and in several cases, it is unclear whether or not Beijing is going to get fully paid back,” says Harry Broadman, a former White House and World Bank official, who is now at the RAND Corporation and WestExec Advisors.

At least 23 zero-interest loans to 17 African countries have been canceled. Beijing has worked with Zambia to restructure some of its debt, but this only accounts for a very small percentage of overall debts. At the October 2023 BRI forum, a revamped debt appraisal framework was announced, the new rules beefed up criteria to assess the economic growth of borrowers, aiming for a more prudent approach in assessing growth risks.

Another pertinent issue is who exactly is party to the deal-making process, given that many of the governments in recipient countries are associated with notable levels of corruption.

“In many of these emerging markets, the people who sign on the dotted line are either heads of government or finance ministers, who frankly, in practice, are somewhat untethered from the bulk of the population’s best interests,” says Broadman. “Moreover, because the countries tend to be less developed, their leaders, too often, don’t face pressure to engage in robust public dialogues. This is an issue that may well come back and bite China insofar as trying to fulfill Beijing’s stated objective of furthering the economic development of the countries.”

More concerns arise with accusations that China acts somewhat like a colonial power by importing Chinese workers, failing to develop local capacity, and extracting resources for local benefit. Some larger and more developed recipient countries have begun to push back, such as Indonesia in a deal with battery manufacturer CATL which requires a certain amount of resource processing to be done in-country prior to export, but many are not in a position to do so.

Additionally, where Chinese-made products and services are incompatible with non-Chinese technology, they can effectively lock countries into purchasing any future upgrades from China.

“There is a role for China to play on a global stage in terms of standard setting for the future of technologies,” says Nedopil Wang. “The way things are, there is a short- to medium-term risk of countries being locked in to Chinese technology, so there is a need for more international standards to avoid this.”

Refocusing

The BRI is currently going through a period of change, something that is to be expected of any initiative of such a scale, and the need for these changes stems from both the natural progression of the initiative over time, as well as the shifting nature of the external environment.

The announcement of a shift in investment towards “small yet beautiful” projects is an example of natural adaptation combined with external pressures. At a fundamental level, there are only so many major infrastructure projects a country needs, and this means that for those that have already built major ports, railways and road infrastructure, any more would be surplus to requirements.

“Smaller is also more sustainable from a financial perspective because Beijing is currently holding a lot of debt from a lot of countries that are not necessarily able to handle that debt,” says the analyst. “The BRI must continue, but doing that in a way that doesn’t saddle China with even more debt relies somewhat on smaller projects.”

At the same time, headwinds at home, caused by domestic economic struggles and exacerbated by the results of growing geopolitical tensions, mean that the state financing of projects may be becoming more difficult.

Also discussed has been the promotion of more yuan-denominated projects as part of BRI investment, which tracks with China’s increasing desire to have the RMB provide a legitimate alternative to US dollar hegemony in international trade. But, as with China’s other efforts to increase international usage of the RMB, how fruitful these efforts will be in the long term remains to be seen.

The other major change in focus of the BRI relates to the types of investment being made and in which sectors, many of which align with the existing national economic priorities in China. This is something of a mirroring of the overcapacity for infrastructure that was originally at the heart of the BRI.

China’s progress in renewable energy has been remarkable, and the country is now a global leader in sectors such as solar power and battery technologies. For solar energy in particular, prices within China are dropping due to an abundant supply, and domestic firms are under pressure to expand beyond the country’s borders.

“There may well be a shift towards diversification in BRI projects, moving beyond traditional infrastructure development to include investments in digital infrastructure, green energy projects, and initiatives focused on sustainability and climate change mitigation,” says Ranaraja.

Alternatives

The BRI is unique in its size and scope, in part due to deals being done between a variety of international and domestic stakeholders from both the public and private sectors. Although there are several multilateral institutions worldwide that offer financing for development projects, such as the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the IMF, there is no single-country-led initiative that matches the BRI.

There are many infrastructure development ‘corridors,’ such as the Japan-led East-West Economic Corridor, several of which pre-date the BRI and may have even facilitated the Chinese initiative to some extent, with many recipient countries viewing them as complementary. After all, for a participant country, receiving a power plant and an industrial park are two separate benefits, regardless of whether they were funded through different initiatives.

In recent years, the US launched the Development Finance Corporation, which partners with the private sector to finance solutions to critical challenges in the developing world. The Biden administration, alongside G7 partners, also announced the Build Back Better World (B3W) initiative as a direct alternative to the BRI in terms of funding, but also with a focus on climate, health and health security, digital technology and gender equity and equality.

But despite their goals, tangible results, particularly in the case of the B3W, have been lacking, and publicity for the initiatives is sparse. “Even at the time of the announcement it was not exactly clear what the B3W was trying to accomplish,” says Broadman. “It came across both through its structure and timing as something of a knee-jerk reaction and doesn’t appear to be particularly well thought out.”

Hitting the road

The BRI is not without its difficulties, including financial fairness, the sustainability of how and with whom deals are made, and the potential impacts of China’s domestic economic slowdown. But on the whole it has been positive for China over the past decade, fulfilling many of its original goals and broadening the country’s role on the international stage as a development actor.

This growing influence means that the initiative has been somewhat subsumed into a larger question of how the world is organized. For some, it is an indicator of an increasingly polarized world, while others argue that it is a part of an overall shift in the global status quo.

“The BRI has 100% been part of a large political and economic shift,” says Nedopil Wang. “China would probably not have been able to do this 20 years ago, but it was 10 years ago and still is now. And it’s able to do it now in a greener way than 10 years ago.”

What also seems clear is that the initiative will continue to exist and develop for as long as the political will domestically remains strong.

“The BRI is here to stay and it’s going to continuously evolve and adapt,” says Chiu. “Over the next few years, it will have to deal with the legacy problems from the first phase, such as debt, and it also has to keep focusing on expanding its new phase, being more targeted, selective in recipient countries, and looking more at the profitability of its projects.”