Stronger Together

Information and expertise sharing are two of the benefits of the more transactional partnerships being pursued by Chinese businesses

On a momentous day in December 2022, the first delivery trucks filled with goods bought via e-commerce rolled out of a massive warehouse in Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC). The deployment of these trucks would drastically slash shipping times between China and Thailand from 10 days to three.

The $300 million ‘Digital Free Trade Hub,’ a joint venture between the Thai government and technology giant Alibaba, is an example of a growing number of more balanced collaborations between Chinese companies and their international counterparts across Southeast Asia.

In the past, technology and knowledge acquisition was the name of the game for China’s businesses, forming part of the context for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and to do this, M&A deals were often 100% buyouts by Chinese firms. But there is now an increase in commercial partnerships formed of joint ventures (JVs) and minority stakes with an emphasis on cooperation over control, and both Chinese businesses and the government are increasingly looking at arrangements with local entities which are more equitable for both sides.

And with rising geopolitical tensions causing a decoupling between China and the West, as well as the growing consensus that there is a need for a fundamental shift in global supply chain structure, China and its businesses are increasingly looking to create a new kind of partnership across Southeast Asia.

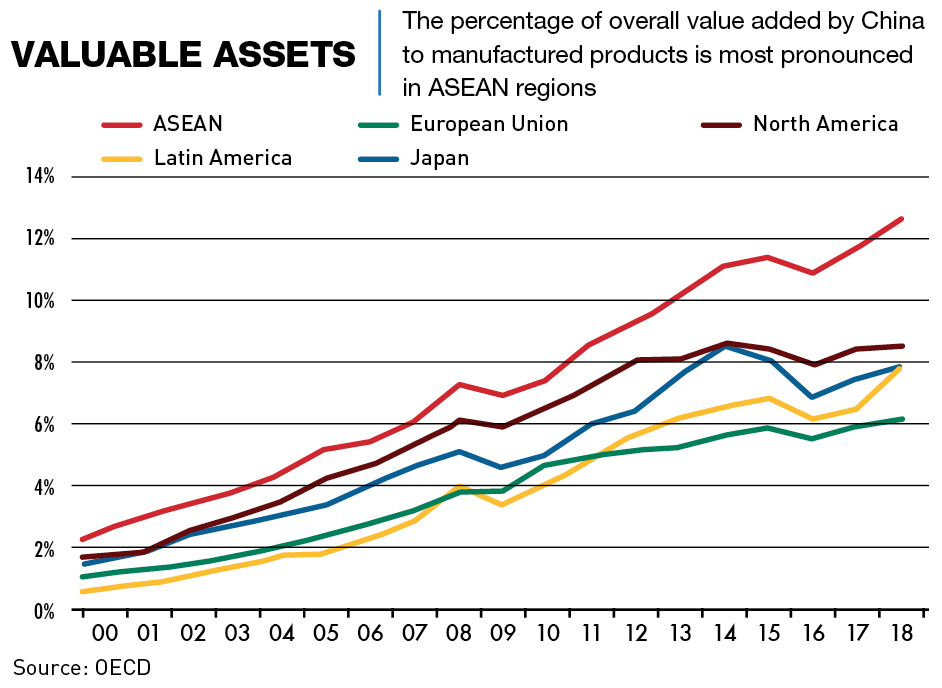

“We are moving towards a type of globalization that is divided into three increasingly independent silos: Asia, Europe and North America with some parts of Asia such as Japan and South Korea,” says Markus Taube, professor and chair for East Asian Economic Studies/China at the Mercator School of Management. “There will of course still be horizontal trade between the silos, but each will become more autarchic. The trends we’re seeing with Chinese business partnerships in Asia is one indicator of this shift.”

Power to partnership

China’s integration into the global value chain started in earnest after the economic reforms enacted by former leader Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s, with the country shifting from an agriculture-driven economy to an export-oriented industrial powerhouse. Prior to the BRI, China’s cross-border collaboration was government-driven and focused on bilateral and regional cooperation agreements, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). This often took the form of provisions of financial and infrastructure support by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), as well as a smaller number of private enterprises, in exchange for access to markets and resources.

The creation of the BRI in 2013 encouraged this further, offering a mass of opportunities for companies to get involved in infrastructure projects across the developing countries of the world, not just in Asia. More recently, membership of multilateral and regional partnerships, such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and increased involvement with the ASEAN region, have spurred China’s businesses to look further afield.

“The core encouragement for Chinese businesses, particularly state-owned enterprises (SOEs), going out into Asia at the moment comes from these regional integration partnerships,” says Taube. “RCEP and the other institutional frameworks, such as the BRI, provide things like guaranteed loans for projects.”

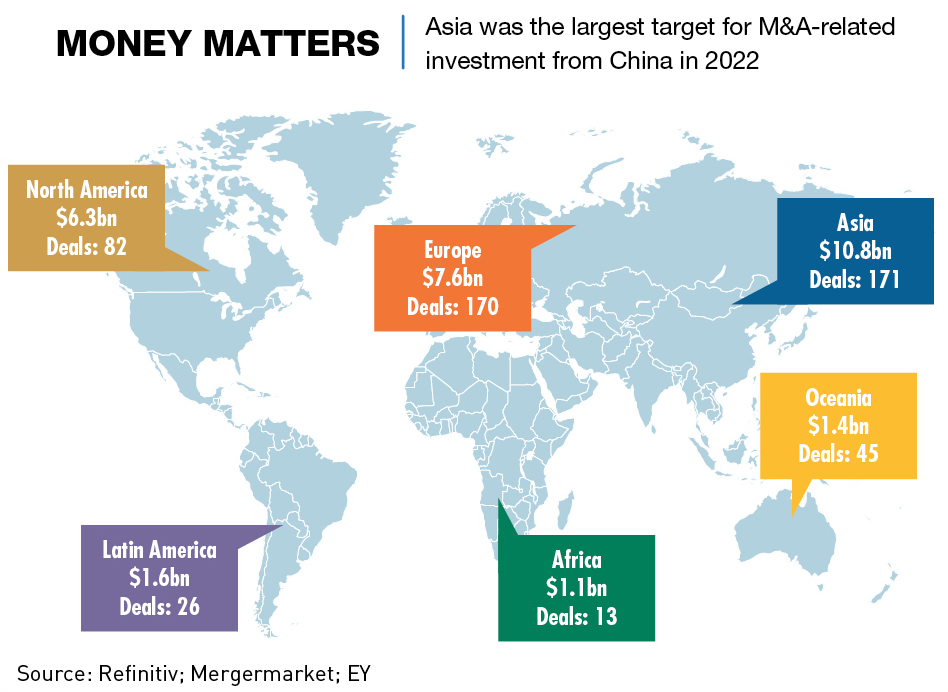

Asia as a whole is now by far the largest recipient of Chinese FDI, receiving $128.1 billion of the total $178.8 billion in outflows in 2021, and much of this money comes from SOEs rather than private enterprises. For example, of the top 100 multinational enterprises active in the ASEAN region in 2021, 65 were Chinese and 46 of those were SOEs.

But China’s rapid economic development has led to an explosion of private enterprise activity in the country, and many of these companies have also sought to expand internationally.

Historically, engagement and money flows stemming from China mostly took the form of M&A deals where the Chinese company would be either the clear majority stakeholder or the outright owner of the local partner. This approach reflects the nature of the Chinese system and the country’s business environment, but can often limit the effectiveness of partnerships through diluting or ignoring the relevant expertise provided by local partners.

The beginnings of a shift in engagement types by Chinese businesses in Southeast Asia, however, was becoming apparent even before the pandemic. More private companies and especially those in sectors related to the digital economy, are now seeking to utilize local partners through joint ventures or more equitably balanced partnerships.

“Chinese investors are becoming more sophisticated, they understand the need and the importance of being able to have constructive discussions with future business partners in the relevant markets,” says Addy Herg, Partner in M&A at Wong & Partners, a member firm of Baker McKenzie International. “They are thinking more holistically and further into the future and making more effort to bridge cultural or practical gaps.”

Despite this, there is still a desire for acquisitions over partnerships in more strategic sectors, such as those related to new energy or electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing.

“The type of collaboration often boils down to why the investment is being made and whether it’s a private or state-owned enterprise looking to make the investment,” says Yuxin Shen, Beijing-based Corporate and M&A Partner at law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer. “For private companies looking to expand their foothold around the world, they are usually happy working with local partners in a more equal relationship. But for SOEs looking to make an investment into a strategically important industry, then that often isn’t so much the case.”

It is also worth noting that, thanks to the myriad COVID-related disruptions to China’s trade and economy, the past few years have been hard to assess in terms of relationship trends.

Good neighbors

In the past, Chinese companies looking overseas were primarily interested in doing deals that would provide them with access to raw materials and cheap labor and this remains true in many areas, especially sectors deemed strategically important. Indonesia, for example, has access to around two-thirds of the various minerals required to produce batteries.

The country is now seeing an influx of Chinese enterprises, both state and private, looking to invest in the sector, with many of them seeking out joint ventures. In April 2022, a subsidiary of Chinese battery giant Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL) signed a tri-party framework agreement worth $6 billion. The deal, which brings together CATL and two Indonesian firms, is designed to develop the Indonesia EV Battery Integration Project, which includes nickel mining and processing, EV battery materials, EV battery manufacturing and battery recycling.

“I think these sorts of partnerships are likely to continue happening,” says Shen. “With geopolitical tensions continuing to rise, Chinese companies are feeling a certain amount of pressure to secure resources wherever they still can.”

As China’s economy has evolved, so too have its priorities and the country’s companies are increasingly looking for partnerships that will help them access new technologies, build brand recognition and establish a foothold in new markets. To do this, Chinese companies are looking to invest in or establish joint ventures with local firms in order to tap into local expertise and gain access to established distribution networks.

At the same time, Chinese companies’ own technological and management knowledge has grown over the years, and they are increasingly able to offer more in terms of expertise to prospective partners.

This has been particularly evident in Southeast Asia, where Chinese companies are partnering with local firms to take advantage of the opportunities provided by the region’s rapidly growing middle class. “Lots of Chinese businesses saw the similarity in current demographic structure in Southeast Asia compared to China 15-20 years ago,” says Shen. “The population is young, there is a mass market for e-business and tech, media and telecom (TMT) companies, so there are lots of opportunities in these areas.”

In e-commerce, Alibaba holds a large stake in the Indonesian platform Tokopedia, Tencent indirectly has the largest stake of Shopee and JD.com owns a piece of Vietnam’s Tiki. All three of these local firms remain under the control of CEOs from their country of origin, but are now able to implement China’s well-honed e-commerce best practices under the guidance of their Chinese partners who also reap the rewards of gaining greater access to a new market.

Chinese carmaker Geely is an excellent example of one company going full-circle, student to teacher. In 2010, Geely bought out Swedish firm Volvo Cars, with both financial motivations and technological and management knowledge acquisition in mind. Geely’s success and subsequent shift in priorities for its partnerships is then evidenced by its 2017 purchase of a 49.9% stake in Malaysian car maker Proton.

“It was almost the opposite, Geely was the much more sophisticated partner of the two,” says Lawrence Jin, Chairman of the Global Chinese Services Group at Deloitte China. “Geely brought some of the best models into Proton, whether that be the manufacturing technology, the supply chain or in product development.”

Not plain sailing

Despite the vast amount of potential benefits, these newer commercial partnerships can often be tricky to execute. The first, and perhaps most obvious issue, is that even with profitability and growth in China, success in a new venture is not guaranteed. JD.com has recently exited the Thai and Indonesian markets—the platforms in both countries were joint ventures with local partners—after failing to beat out other Chinese-backed competitors.

There is also competition from other countries, including Japan and South Korea, whose companies are already embedded in markets. Both countries have been investing heavily in the region, with a particular focus on high-tech industries such as robotics and renewable energy, as well as automotive manufacturing.

“Competition is always going to be fierce because, especially in Southeast Asia, you have the European and US multinationals and the Japanese are very well entrenched in the marketplace,” says Jin. “Toyota is a great example of a company that has already been in the market for around five decades or so.”

This has made it more difficult for Chinese companies to establish a dominant presence in the region, but at the same time, has forced them to become more innovative and competitive in their approach.

Different levels of legal protections have also been barriers to harmonious relationships. In China, trust and good faith both have a higher relevance in the dispute resolution system. This means that if a dispute is brought to court, the court may look into the fairness of the contract and determine which party is being unfairly treated and make a ruling based on that, even if the contract does not expressly provide for the parties’ respective rights and obligations.

“But if you look at the legal systems in several ASEAN countries that follow common law regimes, it’s entirely different,” says Herg. “If you don’t have those terms set out clearly and specifically in the contract, it will be difficult to avail yourself of the intended protections.”

Uncertainty over the similarity of long-term goals is another issue that is increasingly coming to the fore. Given that the majority of partnerships featuring Chinese firms in manufacturing, infrastructure and consumer sectors have been established within the last decade, many are only now reaching long-term status, and they have no blueprint to follow.

“Even with the best intentions, after a while expectations from both parties could start to differ,” says Shen. “Many Chinese companies are still trying to learn how to deal with that phase of the relationship.”

South central

While the more equitable partnership style is seemingly thriving in some areas of the continent, frosty diplomatic relations, among other concerns, are hampering its development in others.

“Chinese partnerships in Asia are trending in different directions in different areas,” says Shen. “Relationships in some areas of the continent are deteriorating a bit, especially when compared to Southeast Asian relations.”

The difficulties with partnerships outside of Southeast Asia are more fundamental, and there are concerns about China’s growing economic involvement in some countries and the potential for it to lead to outsized political influence. This has been particularly evident in countries such as Sri Lanka, where worries about Chinese influence have led to tensions with the local population, and with India where Chinese apps and telecoms companies have come under increased scrutiny.

In addition, there have been concerns about the quality of Chinese infrastructure projects in some of these countries, leading to questions over their long-term sustainability and casting doubts over future collaborations. One such example is Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, which was financed by a large loan from China and completed in 2010. But by 2017, the Sri Lanka government was struggling to repay the loan, in part thanks to the lack of commercial traffic to the somewhat inconveniently placed port, and was forced to lease control of the port to China for 99 years in a debt-for-equity swap.

“Chinese businesses have undertaken a vast number of infrastructure projects over the past few decades, and in many places they have done a good job,” says Stephane Grand, President of S.J. Grand, a professional services firm based in Beijing. “But in some cases, whether the results will stand the test of time is unclear.”

There are some examples of the newer style of Chinese business partnerships outside Southeast Asia. For example, in January 2023 the Indian government granted preliminary approval for 14 Chinese companies to form joint ventures with Indian firms to supply parts to Apple in a bid to develop the country’s electronics manufacturing. They join existing Apple manufacturers Foxconn, Pegatron and Wistron in the country.

But in general, there are currently more barriers than opportunities in these areas.

“When comparing Vietnam with Bangladesh, for example, it is often cheaper, easier and more reliable for Chinese companies to produce the same goods in Vietnam, so they will choose the former because of the stronger market and skilled workers,” says Shen. “Many South Asian countries in particular are limited less by the politics and more by the strength of their market and labor forces.”

Partner preferences

For businesses and governments outside of China, while there are many similarities between how SOEs and private enterprises run, there are also key differences when it comes to engaging in a partnership with either. Stylistically, management and decision-making within either type of company reflects the Chinese way of doing business. The key difference is what each can offer.

“The major difference isn’t the management styles,” says Taube. “It is that the so-called private companies are smaller, nimbler and more able to flexibly react to local circumstances. Whereas the SOEs, in particular the really large ones, can just push themselves into a market. They have state backing, all the finances they need and solid diplomatic support that really helps in securing licenses and permissions.”

While this demonstrates some of the benefits each business type can offer, there are also contrasting drawbacks. “The downside with the SOEs is that the decision-making process can be quite a bit slower since you’re not simply dealing with an entrepreneur who can make an executive decision,” says Edward Radcliffe, partner at Vermillion Partners, a global financial advisory firm. “On the other hand, the private sector can have difficulties getting cash if they are not already flush, and getting funds out of China can also cause delays.”

Southeast Asian companies looking for prospective Chinese partners would appear to prefer private companies over SOEs, but a shift is taking place. “The knee-jerk reaction has always been a preference for private,” says Radcliffe. “But that is changing thanks to Xi Jinping’s reforms as well as COVID. People see the SOEs as more solid and reliable, even if they are slow.”

Coming in

Until recently, a joint venture with a Chinese partner was a legal requirement for a foreign company to be able to operate in many areas of the Chinese market. Although this posed a barrier for certain companies, large especially ethnic Chinese-owned businesses in Southeast Asia have shown an appetite for the country. “These businesses in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia were the pioneers,” says Jin. “They have the cultural linkage and have been here, in some cases, for 40 years or more.”

The JV requirements for almost all industries have been scrapped in the last few years, but COVID-related disruptions replaced it as the main barrier to increasing overseas investment and business involvement in the country.

“There hasn’t been much new in terms of businesses looking to the China market recently,” says Taube. “There has been a small amount of reciprocal investment from some areas, aimed at strengthening existing cross-border business models, but not much. But given that the restrictions are seemingly behind China, there is a logic to expecting an increase over the next few years.”

Together forever?

With the maturing of the first real cohort of Chinese cross-border partnerships, which often took the form of full acquisitions, there are a number of lessons that Chinese private enterprises and SOEs have learned.

“Chinese companies are becoming more farsighted in terms of decision making,” says Herg. “This means that in the future we’re expecting to see Chinese business partnerships increasingly taking the form of joint ventures or other forms of collaboration to enhance their understanding and integration into the respective local markets.”

The changing nature of globalization means that China’s outgoing businesses have been moving away from the West and refocusing on developing their involvement and the value chain in Southeast Asia in particular.

The fundamental intention for many of these businesses is accessing new markets as well as securing strategic supplies, but Chinese companies are increasingly realizing the benefits brought about by having more equitable partnerships with endemic businesses, rather than just buying them out completely or muscling in.

“In contrast to more developed countries which can often be harder markets to penetrate for various reasons, Southeast Asia in particular offers room for rapid development and there are a number of production, consumer and supply chain advantages,” says Jin. “If you look at the global stage and ask where is the right place to go and make money but also help their globalization agenda is, it’s there.”