Chinese companies are globalizing on an unprecedented scale, but with mixed success.

For the investors, it was all backwards. In early 2011, Chinese dairy producer Bright Food convened a meeting with outside investors and consultants. The company had mountains of cash, priceless connections and Beijing’s blessing. Having grown to become China’s second-biggest food and drink company, it was now looking to expand into the UK market. All it needed was something to actually sell there.

“We asked them, ‘So you’re planning to sell Guangming milk [the company’s flagship milk brand] in Manchester?’” says Paul French, founder of market research firm Access Asia and one of the consultants at the meeting. Bright Food executives responded that yes, they were. “We just said, ‘Well then, good luck with that one.’”

The episode, compounded by later failed attempts to acquire brands like United Biscuits and Yoplait, illustrates in part why caution–bordering on skepticism–is by far the most common theme that cuts across conversations with consultants, investors and managers involved in cross-border Chinese expansion.

“Don’t do it,” laughs Torsten Stocker, a China-based partner at the consulting firm Monitor, when asked for the advice he gives to Chinese companies expanding abroad. “Or at least, really think about why you’re doing it. These things sound easy and look great on a Powerpoint slide, but in reality they’re very, very difficult to do.”

That may be an understatement. Of the 300-odd foreign mergers and acquisitions Chinese companies conducted between 2008 and 2010, around 90% failed (by definition of losing 40-50% or more of their initial purchase value), according to a report by the Brookings Institution, a US-based think tank. Many Chinese companies have little experience in M&A, much less of the complexities involved in cross-border M&A.

Get past the obligatory notes of caution, however, and nearly everyone in the field says business is booming like never before, thanks to a combination of bigger and more ambitious Chinese companies, fiercer competition and a slowing economy at home. Outbound Chinese investment grew by an average annual rate of 45% between 2002 and 2011. It surged by almost 50% in the first half of this year, and the sub-category of outbound mergers and acquisitions jumped by 29%, according to data from Dealogic. China is now the world’s sixth-biggest global investor, and is on track to invest $1-2 trillion abroad by 2020, estimates the research outfit Rhodium Group.

Moreover, the global success of at least some Chinese companies is now undeniable, bolstered in no small part by their dominance in the world’s second-biggest economy. Haier is the world’s largest manufacturer of major home appliances by volume. Huawei is the biggest telecoms equipment maker. Lenovo may soon overtake HP as the largest computer maker. PetroChina is the world’s fifth-biggest resource company.

Chinese companies vary widely in why they choose to go global, how they go about it and their ultimate success. But those studying and involved with cross-border Chinese investment say it is still possible to tease out some basic patterns and approaches, and identify what works–and what doesn’t.

Sell Where You Know

By far the most common approach cited by those in the field is for Chinese companies to first expand into other emerging markets. Over 80% of China’s outbound investment in 2011 flowed into developing countries (though that figure also includes resource-related investments), according to the National Bureau of Statistics. There are compelling reasons why Chinese companies generally find emerging markets a natural springboard for international expansion.

For starters, many industries in developing countries are underserviced by big developed-world companies, which offer products that are either ill-suited or too expensive for local consumers. They provide an opportunity for low-cost Chinese manufacturers to edge in, usually without the need to overhaul their products.

Take the Chinese motorbike manufacturer Chongqing Lifan Industry, today a major auto manufacturer with annual revenues of around $1.37 billion. In the late 1990s, China’s motorbike industry was in a painful squeeze; supply far outstripped demand, forcing manufacturers to slash prices to break-even levels. In an industry with plenty of deep-pocketed state-owned companies, the seven-year-old Lifan’s chances didn’t look good.

Then the company’s CEO, Yin Mingshan, took a trip to Vietnam. He found that country’s motorbike market almost entirely supplied by Japanese brands like Honda and Suzuki, which were far more expensive than Lifan’s own “Hongda” brand (itself more than a little inspired both in name and design by Japanese auto makers).

In 1999 Lifan moved in, selling and distributing motorcycles at lower prices than comparable Honda and Suzuki bikes. Even so, they were still priced higher than what the same Lifan models were going for back in China, and Lifan pocketed the difference. The company then took those profits and used them to subsidize its sales at home, thereby gaining market share.

Within two years of entering Vietnam, Lifan leapt from a middling player to China’s biggest motorcycle manufacturer. Today it exports vehicles to over 160 countries and regions around the world, and sales abroad accounted for over 40% of the revenue it generated in 2011.

Lifan is the model many other Chinese manufacturers look to when going global, says French of Access Asia. Not only do many also find themselves with products that could sell well to consumers in other emerging markets, but they also look to foreign expansion as a way to subsidize their operations back in China.

He pointed to Haier’s expansion in Africa as another example with a similar strategy. The appliance maker has sold cut-price air conditioners, washing machines and refrigerators in the region for nearly two decades. Haier then pools revenues from these lower-end products to fund R&D and sales of premium and higher-margin appliances at home in China and in other, more mature markets.

Finding the Bottom Billion

Some companies also say they their experience in China gives them a better feel for what consumers in developing countries are looking for.

“We’ve gotten really good at developing technologies and products that are appropriate for [emerging] markets,” says Kaiser Kuo, director of international communications at Baidu. The internet search giant is currently making forays into Egypt (where it can access users across much of the Arabic-speaking Middle East), Southeast Asia and Brazil.

These are early days, but the company is optimistic about its prospects in emerging markets. Unlike Baidu’s ill-fated venture into the Japanese market, where it met stiff competition from Google and Yahoo! Japan, there are few dominant players in developing countries, says Jennifer Li, Baidu’s CFO. Perhaps even more importantly, she argues that Baidu’s experience with Chinese users in rural and less developed areas has helped it learn how to cater to less sophisticated consumers.

“The beautiful thing is people who are from less developed, less sophisticated markets, they actually expect more of technology, so it is actually a spur to innovation,” says Kuo. He cites the example of rural Chinese users who are unfamiliar with traditional smartphone inputs. To better serve these users, Baidu has ramped up investment in voice-enabled inputs and application activation–a technology that could transfer well into other developing countries.

“It doesn’t require us to make a ‘dumbed-down’ version–quite the opposite, in fact,” he said. “We actually make smarter products.”

These “smarter products” may also be a gateway into more mature markets like the US, Europe and Japan. Steven Veldhoen, a Beijing-based partner at the consulting firm Booz & Company, points to a new trend of what his company calls “mid-market innovation”: Chinese companies expanding into developed countries by selling low-priced but adequate-quality (“good enough”) products. These companies target the high end of bottom-tier markets and the low end of top-tier

markets.

To illustrate the trend, Booz points to Mindray Medical International, a Shenzhen-based medical devices company. The firm started in 1991 by supplying low-cost but functional in vitro diagnostic tools and life support systems to Chinese hospitals. Each year it ploughed about 10% of its revenue back into research and development to refine its products.

Beginning in the 2000s Mindray discovered that American hospitals were also interested in its “good enough” systems. In 2006 it listed on the New York Stock Exchange, and now ranks both as China’s biggest medical equipment provider and a strong player in the US market.

Mid-market stories are inspiring, but serious caveats apply. For one, almost all Chinese companies that have achieved a measure of success in mature markets–such as Huawei and Lenovo–derive a large share of their revenues from business-to-business (B2B) operations.

This is particularly true in the field of industrial equipment, where China’s building boom has given rise to a handful of companies that have developed the scale, capital and products to smoothly transfer business into other markets, argues Xiang Bing, Founding Dean and Professor of Accounting at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, in a recent report on Chinese corporate globalization.

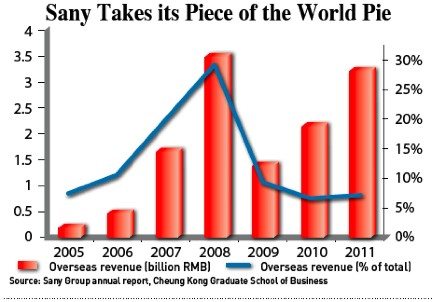

He points to the example of Sany Heavy Industry, an industrial equipment maker whose overseas sales jumped from around 2% of total revenue in 2005 to around 30% last year. That year the company purchased Putzmeister, a German concrete pump maker, instantly giving it access to several new markets across Europe, Asia and the Americas. The company said its international revenue more than doubled in the first half of 2012, buttressing the construction slowdown at home.

Model or a Fluke?

A notable exception to the B2B rule may be Haier. It entered the rich world by targeting the niche US home appliance market of student dorms and small fridges in the early 1990s, then expanded outwards. It has a modest presence in Europe (about 1% of large appliance market share), and thanks to a series of aggressive acquisitions this year now has a sales and a distribution network throughout much of Japan and Southeast Asia. Most recently, in September the company made a bid for Auckland-based appliance manufacturer Fisher and Paykel, giving it greater access to Australia and New Zealand.

But the jury is still out on Haier’s chances of success in mature markets, according to consumer goods analysts. Moreover, the home appliances industry may be so unique that Chinese companies cannot easily replicate Haier’s model in other sectors. “I think what Haier is doing works for Haier,” says Stocker of Monitor. “But is it something that Chinese consumer goods companies in other sectors can follow? I would say no, because in other sectors both the demand dynamics and [competitive] landscape are different.”

Haier aside, Chinese business-to-consumer companies tend to fare poorly in the US, Europe and Japan. “There aren’t too many examples of Chinese [consumer] brands that have done a stellar job of succeeding in developed markets,” said Jessica Vaughn, trends strategist at marketing firm JWT and author of Remaking Made in China, a report on Chinese branding in developed markets.

Making inroads with consumers in these markets requires lots of time and money to develop brand equity, she argues not least because Chinese brands must grapple with the ‘Made in China’ stigma of inferior quality. While some, such as Lenovo, TCL, Haier and others have launched marketing campaigns in rich countries, they “are still fighting an uphill battle,” says Vaughn, and predicts that a “slow and arduous” journey to Western markets lies ahead.

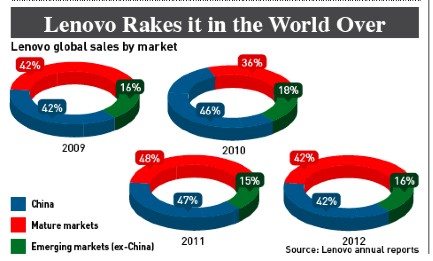

To be fair, mature markets are tough for Chinese companies of any stripe, says Siu Fung Chan, a Shanghai-based partner covering technology and industrial equipment at Monitor. He notes even Chinese companies that appear to be thriving in mature markets are not examples of unambiguous successes; Huawei makes headlines in Europe but still generates most of its revenue from emerging markets, and Lenovo, which acquired IBM’s PC unit in 2005, has squarely focused most of its expansion efforts on countries like Brazil, Russia, and India .

Part of the problem is that, as Baidu discovered in Japan, industries in mature markets are usually dominated by powerful incumbent players. What’s more, the competitive and regulatory environment in developed countries is often very different from what Chinese companies are used to at home. Various forms of protectionism also play a role, such as America’s Committee for Foreign Investment in the United States (CIFIUS), a panel that screens Chinese investment and has repeatedly blocked deals.

This mismatch was behind one of the most spectacular blow-ups of Chinese outbound investment, the acquisition in 2005 of Siemens Mobile by BenQ, a Taiwan-based mobile handset manufacturer. At the time, BenQ was among the world’s biggest low-end manufacturers of mobile phones, pumping out cheap handsets for the likes of Nokia and Motorola. But its ambition was to move upmarket into the more high-margin branded mobile phone market, and when Siemens put its mobile division up for sale, BenQ pounced.

But the company belatedly discovered that European labor market rules restricted its plans to fire the German workforce, close European factories and move the production line to Taiwan. After floundering for little more than a year, the acquired unit declared bankruptcy in 2006. Some analysts say BenQ, which wrote off nearly the entire $1.1 billion investment, never fully recovered from the fiasco.

Bringing it Home

Many of the most successful Chinese expansions into mature markets don’t involve selling anything there at all, says Andre Losesekrug-Pietri, founder and CEO of A Capital, a fund that helps Chinese companies invest abroad.

“You have a lot of Chinese companies that are really waking up to the fact that they have rising laborcosts but they don’t have a brand or technology,” he said. “So when you look at these companies, they’re still growing very fast, but the margins are getting thinner and thinner.” In response, many are now looking to acquire foreign technology and human capital in order to boost competitiveness back home.

To illustrate this point, Chan of Monitor pointed to a deal announced in August in which Wanxiang Group, one of China’s biggest auto parts makers, agreed to pay $465 million to acquire A123 Systems, an American battery maker.

A123 was founded in 2001 to develop advanced lithium-ion battery technology for use in electric and hybrid vehicles in the US. When the market for electric cars failed to take off as quickly as the firm expected however, A123’s share price collapsed.

For Wanxiang, the acquisition provided a chance to purchase next-generation electric battery technology, production facilities, as well as the company’s talent (Wanxiang’s memorandum of understanding with A123 includes plenty of incentives to keep the brains on board). The acquisition also bolsters Wanxiang’s position in the Chinese auto parts market, because A123 was a supplier to one of China’s biggest auto manufacturers, Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation (SAIC).

For Chinese companies looking to acquire operational know-how rather than assets or patents, minority equity stakes are the more popular route of choice. By taking a minority stake in experienced Western firms, Chinese companies can usually strike side deals to swap employees, customers and advice on improving operations at home in China. Such minority equity stakes made up a whopping 70% of Chinese investment in Europe during the second quarter of 2012, according to figures from investment fund A Capital.

They have been particularly useful in the natural resources sector because they avoid the political backlash that could come with full takeovers, says Thilo Hanemann, research director at Rhodium Group.

China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), for example, made a $18.5 billion offer for US-based oil and gas firm Unocal in 2005 that was blocked by opposition in Congress. After withdrawing its bid, CNOOC re-focused on acquiring unconventional oil and gas extraction techniques from North American companies for use on shale deposits in China.

The company re-entered the American market in 2010 when it bought a $2.2 billion minority stake in Chesapeake Energy. It has since increased that stake, and taken additional stakes in MEG Energy, Norway’s Statoil (which owns some US-based resource assets), and others. “In many cases, it has worked out better than 100% ownership,” says Hanemann.

A Bright idea

Yet for all the clever and counter-intuitive reasons Chinese firms choose to go global, few are as unexpected as that of Bright Food. After the meeting with investors last year, the company announced in May 2012 that it would purchase a controlling stake in Weetabix, an iconic UK cereal brand, in a deal that valued the company at nearly $2 billion.

Breakfast cereals are a fast-growing market in China, particularly in the muesli category (in which Weetabix owns the valuable Alpen brand). Besides distribution opportunities in China, Weetabix could lend Bright Food some brand

cachet.

But cereals (and foods of any kind) tend to be unique to certain regions, and it will be tough to transplant Weetabix’s offerings to the China market, say analysts. While these are still early days, neither Bright Food nor Weetabix has yet announced any plans to make major changes to their product line-up or distribution. French of Access Asia says he’s spoken with executives at Weetabix, who report that Bright Food has taken a hands-off approach to the company.

Rather, the acquisition probably had a much more mundane purpose. “The logic [to the takeover] is that you’ve got a lot of cash in a very high currency that you need to do something with,” says French. With asset prices in the US and Europe at record lows, Bright Food reckoned it was a good time to go shopping for Western food brands.

If the British economy improves it could yet prove a smart buy, especially considering the alternatives. “What else are you going to do with the money? Maybe buy a chain of hotels in Hainan or something,” French muses.

That one of China’s biggest outbound deals of the year might simply have been a portfolio investment will disappoint those in the British press who muttered darkly about a Chinese state-owned company stealing their prized cereal brand. But Chinese companies have long defied easy assumptions, and will no doubt continue to do so as they globalize and achieve success at an international level. After all, says French, they never really planned to sell Guangming milk in Manchester.

Double Take

When international expansion is an expensive marketing campaign

On the surface, Bosideng is just another Chinese company going global. In July the apparel company launched its first foreign store right in the heart of London’s swanky Oxford Street shopping district offering expensive, limited edition suits for men.

Dig deeper, however, and Bosideng is unusual. It is well regarded in China not for its high-end menswear but for its mid-range down jackets. Odder still, most of the advertisements at its London store are almost entirely in Chinese–hardly enticing for attract British customers. What’s going on?

It’s all about branding, says Paul French, founder of the market research firm Access Asia. Bosideng is globalizing and its London store is aimed at Chinese consumers. The company is hoping that newly affluent Chinese consumers will see its upscale store as they tour the city, leaving them with the impression the company is becoming a global brand and encouraging them to purchase more Bosideng products back home.

It’s a risky gambit, and French is skeptical it will pay off, especially given the high costs. “Not many people are going to be willing to follow Bosideng’s lead when they discover the rents in central London,” he said.

Many other Chinese firms have run foreign marketing campaigns to attract the attention of Chinese eyeballs. Yili, a diary company, bought ads on 400 of London’s red double-decker buses during the Olympics, many only in Chinese. Sportswear retailer Li Ning launched a store in Portland, Oregon in 2010, but closed it this year in the face of tougher business at home.

Chinese companies are always eager to gain a “seal of approval” from Western icons and brands because it boosts Chinese labels in the eyes of consumers, said Jessica Vaughn, trends strategist at marketing firm JWT. She noted that Li Ning and its rival, Anta, have recently struck deals with foreign sports talent, including US basketball player Kevin Garnett. Meanwhile, Meters/bonwe, a mid-range Chinese apparel company, purchased product placement space in the Transformers movie, and has been collaborating with the online game World of Warcraft.

Reports suggest the product placement approach is enjoying some success, said Vaughn. For all its chutzpah, the same cannot yet be said of Bosideng’s London play.

(Image courtesy Flickr user harry_nl’s photostream)