What is the state of stem cell research in China? Who is positioned to make the most money from stem cell therapy, and who or what will stand in their way?

Hours after delivering her first baby, Oscar, in November 2011 at the International Peace Maternity and Child Health Hospital in Shanghai, Cecilia Huang readily agreed to store the umbilical cord at a private facility for future use.

After stumping up RMB 20,000 for the initial processing, Huang will pay an annual fee of RMB 2,000 to bank the cord and its blood until Oscar turns 18. There is a good reason for spending so much to preserve something that is usually binned after birth—a potentially life-saving reason.

Umbilical cord blood is rich in stem cells, one of the most revolutionary and controversial topics in medicine today. Stem cells are believed to have huge curative applications because they can both reproduce themselves and transform into any kind of tissue in the human body. The cells could one day be used to treat Oscar if he ever fell ill with certain diseases, such as diabetes, heart failure and liver disease. They even have the potential to treat rare conditions that affect the brain and muscles—such as Parkinson’s and motor neuron disease—and autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus.

“All those diseases are incurable right now. We don’t have much to do for victims. That’s why stem cells have given such hope to patients,” says Guo Wei, professor and researcher at the Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center of Tsinghua University.

“Stem cells are of great importance. They might revolutionize our future medicine,” says Xu Xiaochun, Chairman and Chief Executive of Boyalife Group, which is engaged in stem cell banking.

Cord blood is particularly rich in hematopoietic stem cells, which can be used to create blood cells for transplants. These cells also could help Oscar’s family, as there is evidence to suggest the match between donors and recipients does not have to be as exact as it does for the other two sources of blood cells, bone marrow and circulating blood. Other stem cells, known as pluripotent cells, are what excite researchers today because they can potentially become almost any cell in the body—from muscle and nerve to heart and brain.

In the US, eight to 10 in every hundred delivering families opt to preserve their stem cells, according to Xu. In Hong Kong, that rate rises to one in five families, but in China, only Beijing comes close with a proportion of 14%. “In the entirety of China, the current number of families that have chosen to preserve is 0.7%. It’s almost like a brand new market.”

The field of stem cells falls under something called ‘regenerative medicine’ that Ajan Reginald, Executive Director of Cell Therapy Limited (CTL) from the UK, calls “the 21st century breakthrough in terms of medical innovation”.

“Current medicines often treat symptoms very well but they don’t actually repair the underlying problem—in this case, the underlying tissue of the cell. Regenerative medicine gives you the ability to repair tissue. Stem cells are the core technology behind regenerative medicine.”

Some of the touted applications for stem cell technology sound like science fiction, with talk of growing new organs and halting the aging process. But what sounded impossible a decade ago is beginning to become a reality, with the list of body parts grown from stem cells getting longer and longer—from ears and eyes to livers and kidneys, and even a heart.

“Some people say it could have an effect on aging, but this needs deeper study,” says Fu Xiaobing, the Director of the Wound Healing and Cell Biology Laboratory in Beijing and President of the Chinese Tissue Repair Society.

“The sky is almost the limit, but to be realistic, [the stem cell field] is working currently on a list of 10-20 different diseases that we think have the highest potential,” says Xu.

A Dose of Ethics

Perhaps more than any other field of science, the study of stem cells has been shaped by political opinion and subject to ethical objections. For much of the last decade, stem cell science was viewed negatively in the US. Devout Christians criticized the creation and destruction of days-old embryos for research, guided by their religious beliefs that embryos were emerging individuals. Elsewhere, the idea of producing embryos solely for scientific experimentation appalled people from more varied walks of life.

The debate became heated and politicized. Pope John Paul II called it a “cannibalization of embryos”. Then in 2001, US President George W. Bush limited federal funding for research on stem cells obtained from human embryos. That moratorium—lifted more than seven years later by Barack Obama in 2009—has left the US “years behind” leading stem cell nations, according to Reginald from CTL.

The debate became heated and politicized. Pope John Paul II called it a “cannibalization of embryos”. Then in 2001, US President George W. Bush limited federal funding for research on stem cells obtained from human embryos. That moratorium—lifted more than seven years later by Barack Obama in 2009—has left the US “years behind” leading stem cell nations, according to Reginald from CTL.

The debate in the US and West sharpened scrutiny on the morals and ethics of Chinese stem cell research, to the chagrin of some in China who chafed at what they perceived to be smug Western lecturing and condescension.

China has debated but not dwelled upon the ethical dimension of human embryonic stem cell research. The absence of outcry has been partly attributed to a Confucianist view that a person begins at birth, as people are shaped and defined by their closest social relationships—which embryos lack. Then there is the ‘utilitarian’ argument that embryo research is justifiable if it brings enormous welfare to people that cannot be otherwise achieved. Furthermore, the years of pervasive sex-selective abortions and infanticides in China could be seen as evidence of a cor-ollary cultural detachment from the value of a fetus or embryo, which contrasts starkly against some viewpoints in the US. China’s treatment of abortion may have normalized the practice, paving the way for societal acceptance of embryonic stem cell research. Also fueling interest are reports that tissue from aborted fetuses is a source of stem cells. New discoveries and advances in recent years have also dampened some of the moral controversy by sidestepping thorny ethical issues. A major breakthrough came in 2007, when two independent teams at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the US and Japan’s Kyoto University reprogrammed adult human cells to form pluripotent stem cells, negating the need to depend on embryonic tissue for stem cells. For his pioneering work at Kyoto, Shinya Yamanaka earned the Nobel Prize in medicine in 2012.

It is probable that in any case, ethical qualms would have taken a backseat to the Chinese government’s desire to move from ‘made in China’ to ‘innovated in China’. Stem cells fit in with Beijing’s ambitious plans to vault the country to the top of the research ranks. In 2001, the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology formed two independent stem cell programs under the National Basic Research Program—a special national research initiative better known by its ‘973’ moniker.

Since 2002, China has pumped money into the field through multiple sources. The ministry has provided abundant research funding through the 973 plan and a separate ‘863’ program—grant sizes from both can reach up to $5 million, with the difference between the two being that the former focuses on basic research and the latter on applications. The National Natural Science Foundation of China has also contributed grants, boosting funding from just over RMB 100 million in 2008 to more than RMB 450 million in 2012.

Chinese researchers are forging ahead in the field, backed by the substantial grants from central agencies and local governments too. And keen to reverse a so-called ‘brain drain’, Beijing has enticed Chinese scientists educated at top universities in the US and Europe to return home with the promise of competitive salaries, funding and leadership of labs staffed with eager young researchers.

While China smelled an opportunity to steal a march on the dawdling West, its interest in stem cells has more pragmatic reasons. The Chinese are aging quickly, with more than a quarter of the population set to be older than 65 years by 2050.

The scale of China’s greying could place an enormous strain on the healthcare system, as the number of people with degenerative diseases grows. China already has more people with dementia than any other country, while a new study suggests two out of every 100,000 in the nation have Parkinson’s. Stem cells then could allow China to stave off a healthcare crisis by offering much-needed treatments for these chronic illnesses.

Ceiling Up

China’s success in stem cells will depend on more than raw government investment in human capital like young scientists and material assets like labs. But the strategic state support and willingness to engage in stem cell science for the sake of national prestige and to ease looming healthcare problems has turned China into an attractive destination for stem cell companies to test their therapies.

Nasdaq-listed Neuralstem, for instance, teamed up with Beijing’s Bayi Brain Hospital—an institution affiliated with the Chinese military—to treat motor deficits from ischemic stroke by transplanting spinal cord stem cells directly into the patient’s brain near the stroke lesion. Neuralstem, which declined to be interviewed for this article, announced in January that the first patient had returned home after undergoing the treatment in late December.

CTL, meanwhile, agreed in July 2013 with Zhongyuan Union Stem Cell Bio-engineering to jointly invest $8 million in a new venture to commercialize findings from their stem cell studies.

“China is an exciting, enormous market with great potential and so we wanted to be at the forefront,” says Reginald. “There are very few Western companies coming to China to undertake breakthrough technology research. There’re very few people considering China as an innovation centre, and that’s what we wanted to do.”

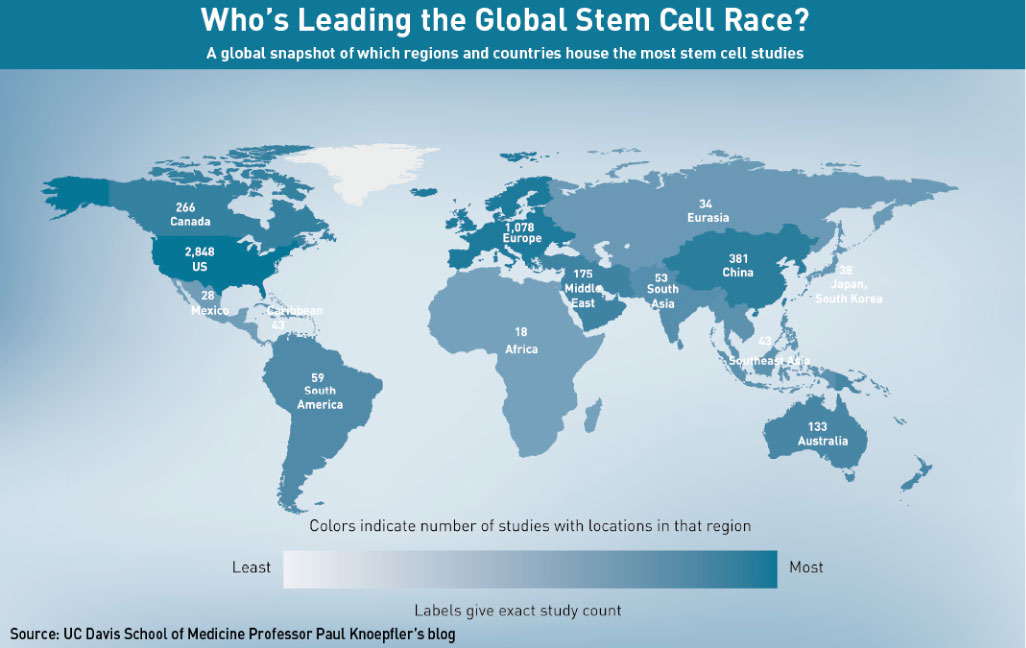

The number of stem cell-based clinical trials underway in China underlines the country’s rush into the field. China has the third-highest number of ongoing stem cell clinical trials in the world, at 164 studies, according to the US National Institutes of Health, second only to the US and Europe. In research output too, China is quickly catching up. A comprehensive report released last December, by Elsevier, Kyoto University’s Institute and EuroStemCell for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences, found that since the beginning of 2006, China has been the “second most productive country by volume of publications”. China’s growth curve, said the report’s authors, “is strikingly similar to that of the USA”—currently the biggest contributor of stem cell papers.

The volume is impressive, but quantity is not always commensurate with quality in Chinese research. The report noted another important development: China’s citation impact, though below average, had increased during the study’s assessed period of 2006-2012 and demonstrated a strong growth rate across all types of pluripotent stem cell research.

For all its progress, however, any assumption that China is helping to pioneer breakthroughs in stem cell science may be misplaced. The country is “not really” producing cutting-edge stem cell research, according to Reginald.

“China lags in medical innovation as a whole, so the lagging in stem cells is not really surprising,” he says. “China is excellent at a number of things but breakthrough technological innovation, es-pecially in the medical area, is not there yet. The government and universities are focusing on this but it takes a long time for this commitment to generate innovation.”

It is China’s neighbor to the east that is making great strides in stem cells. “The Japanese really are at the very forefront, and that’s not just because of Shinya Yamanaka—who won the Nobel Prize recently—but there’s also a halo effect,” says Reginald. “A lot of the great breakthroughs are coming from Japan.”

“Ten years ago Japan implemented a clever strategy in selecting the niche of regenerative medicine and a particular group in Kyoto of Shinya Yamanaka. In essence Japan decided that within medical innovation, they were going to be the leaders in regenerative medicine, and it looks to have paid off.”

Chinese scientists are keen to apply stem cell research to treating patients but public awareness of stem cell therapies in the country remains on the periphery. Part of that is due to the lead time for medicines to go from theory to practice.

“Stem cells are still considered a cutting-edge technology. [The lack of awareness] is directly related to education. A lot of people are not aware of stem cells, and there is no good public education for letting people know there is this science called stem cells,” says Xu.

He contrasts that with the US, where 24 states—covering more than two-thirds of the births in the nation—have passed laws that obligate healthcare providers to educate expectant parents about their options for saving a newborn’s cord blood stem cells after birth.

“Regenerative medicines are very new. Breakthroughs in the lab may take 15 or 20 years to convert into medicines in the public domain,” says Reginald.

“Doctors need to be convinced and for that safety is key. Things will go faster but we’re just at the stage where the first regenerative medicines are producing compelling data. You don’t just need good data—you need validated data that absolutely demonstrates that stem cell therapies are safe and effective. We’re just beginning to see that now,” adds Reginald.

Hazardous to Health

Healthcare providers in China have been enthusiastic about using stem cell treatments, in contrast with the rest of the world where such procedures are still undergoing clinical tests. The fear is that hospitals and private treatment centers engage in fraud by offering dubious stem cells to desperate patients without adequate oversight.

“There are rogue companies—some are pretty well-known—that have been using stem cells to treat virtually anything if you are willing to pay,” says Xu. “The majority are unproven. People are paying up to half a million yuan for a completely unproven therapy.”

Numerous stories abound of desperately ill patients with incurable diseases encouraged by slick sales pitches to book therapies that are backed by little or no scientific evidence and are at best experimental. In many cases, they are charged thousands of dollars.

On a tree-lined stretch of one of Shanghai’s busiest roads lies the PLA 455 Hospital. In one high-profile case from 2010, Hong Chun, a 27-year-old diabetes patient from a midsized city in Zhejiang province fell ill the day after undergoing stem cell treatment at the hospital. Hong, who reportedly paid RMB 30,000 for the transplant, was rushed to another hospital and died a month later.

Authorities’ efforts to tackle the proliferation of unsupervised stem cell treatments by tightening policies date back almost five years. In May 2009, the health ministry classified all therapies as “category 3” medical technologies, deemed as “high risk” and “ethically problematic”, with clinical trials needed to verify their efficacy and safety.

Then at the start of 2012, the government announced a regulatory crackdown, halting new applications for clinical trials of stem cell products to improve the industry’s development. But those rules went unheeded, as hospitals and private clinics continued to offer treatments.

Since May 2013, only top-tier hospitals certified by the country’s State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA) have been allowed to apply to hold stem cell treatment clinical trials—with such tests free for patients involved. Experts say that has helped improve the regulatory environment, with policies now on par with those of the West.

“The regulation’s pretty strong,” says Reginald. “You can only undertake stem cell therapies in the most sophisticated hospitals, which are typically hospitals affiliated with universities. We’ve found the regulatory environment in China to be as stringent, if not more stringent, than what we have in Europe.”

Other insiders disagree with that assessment and have reservations about the latest ministerial ruling that confines clinical tests to elite institutions. Xu from Boyalife argues the move has “conflicts of interest”, spurring dubious firms to partner with hospitals fitting the SFDA criteria.

“Each health center will have a few clinical sponsorships, and those sponsors are most likely to influence the outcome. It creates a conflict of interest,” says Xu.

Future Perfect?

Formidable hurdles remain. According to Fu, a major problem hindering the development of new therapeutics is poor coordination. “In many settings, the clinic and the basic research laboratory are often completely different,” he says.

“Basic and clinical scientists, as well as scientists working in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries need increased awareness of the questions that must be answered before a stem cell-based product can be used clinically.”

On the corporate front for both foreign and Chinese companies is the well-worn issue of protecting intellectual property (IP) in a field where treatments can take tens of millions of dollars to research and develop.

“For stem cells, the IP protection technology is more complex than for conventional drugs, as for those you can simply draw a formulation or a structure and clearly define how it’s protected,” says Xu.

If it were only a matter of money, then China’s desire to become a future hub of world-class stem cell science would be assured. But all the billions of yuan pouring into the research field will take years and perhaps decades to translate into meaningful applications, with setbacks and false starts along the way. Patience will be key for a field that promises so much but where safety is paramount, and it’s a mantra that Chinese scientists are preaching.

“There’s a lot of hype and expectation,” says Kee Kehkooi, Professor at Tsinghua University. “That’s the challenge, whether we will be able to cope from all the pressure.”