The problem of industrial overcapacity in China has assumed massive proportions. How can it be solved now that fiscal measures are becoming increasingly ineffective?

For more than a decade, Chinese policymakers have promised to rebalance the world’s second-largest economy. The objective has been to transition to a new growth model fueled by services and consumption instead of fixed-asset investment. At the National People’s Congress in March 2007, then-Premier Wen Jiabao warned: “The biggest problem with Chinaʼs economy is that the growth is unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable.”

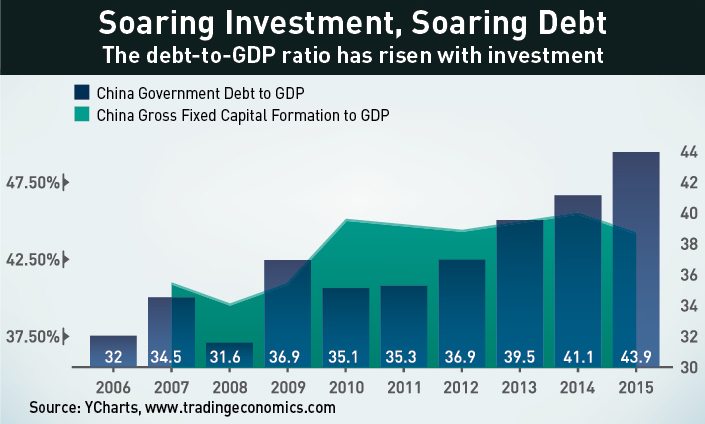

Wen’s words have proven prescient. In 2007 China’s GDP growth peaked at 13%. It then began a long deceleration in 2008. That was interrupted only by a massive fiscal stimulus package that shielded China from the worst effects of the global financial crisis but aggravated imbalances in the economy as wasteful spending ballooned.

Having delayed serious structural reforms, China faces eye-watering overcapacity in heavy industries. Steel production volume is more than double that of the next four leading producers combined: Japan, India, the United States and Russia. Aluminum production capacity reached 40 million tons last year, exceeding global consumption by 9 million tons, according to Chinese think tank Antaike. Most remarkably, between 2011 and 2013 China produced more cement than the US did during the entire 20th century—6.6 gigatons, compared to the US’s 4.5—according to data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics and the US Geological Survey.

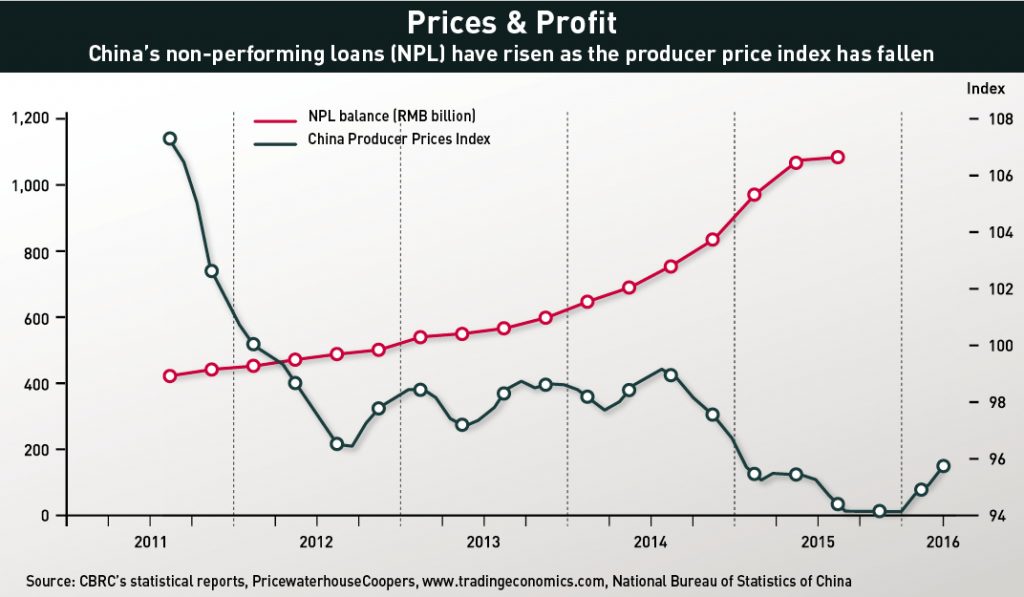

That excess capacity is weighing on the balance sheets of debt-ridden firms reeling from China’s economic slowdown. China’s producer price index fell continually during the 45 months up to December 2015. Non-performing loans reached a 10-year high of RMB 1.27 trillion ($195.63 billion) at the end of last year.

At the same time, tensions between China and its biggest western trading partners are rising as the European Union and United States move to curb cheap Chinese steel imports.

“Investment-driven growth has worked for China in the past,” says Gan Jie, a professor of finance at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB). “The manufacturing sector was pretty much developed by firms blindly pursuing short-term profits. But one day demand just wasn’t there anymore.”

Measures to contain overcapacity have been ineffective thus far. Local governments have growth targets that rely heavily on tax revenue from overcapacity industries and chafe at the idea of mass layoffs. “When things go sour, these firms would like to exit, but local governments look at that as destabilizing,” says Li Wei, an economics professor at CKGSB. “If all these workers are laid off, what are you going to do with them?”

Still, China has vowed to address its overcapacity problem with aggressive supply-side reform. Beijing says closing down debt-ridden “zombie” firms—bankrupt companies kept alive by loans from state banks and other government support—is a key policy priority for 2016. “For those ‘zombie enterprises’ with absolute overcapacity, we must ruthlessly bring down the knife,” Premier Li Keqiang said at a meeting of economic advisors in December.

But experts say Beijing’s planned measures are likely insufficient. “The government has announced concrete action to reduce overcapacity in coal mining and steel and I expect the authorities to make progress in this regard,” says Louis Kuijs, head of Asia economics at the research firm Oxford Economics. “However, compared to the problems, the plans are relatively timid and overcapacity is unlikely to be reduced sufficiently in the coming two years.”

A Legacy of Overcapacity

The origins of China’s industrial overcapacity are deep-rooted, a legacy of the nation’s planned economy that existed from 1949 to 1979. In a planned economy, the production of capital goods can continue regardless of whether there is demand for the goods they are used to manufacturing, notes Yongding Yu, director of the Institute of World Economics and Politics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, in a 2013 proposal addressing China’s overcapacity problem. “It is common in China that when there is no strong demand for consumer goods that use steel as input, steel will be used to produce capital goods. In other words, to absorb the excess supply of steel, more steel mills are built,” he wrote.

While China has undertaken major economic reforms since 1978, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) retain an outsized role in the economy. Many of the largest SOEs dominate heavy industries like steel, coal and cement. SOEs have thrived on access to easy credit from state banks and government-set rules that limit competition from private companies.

Beijing launched aggressive SOE reforms in the late 1990s as surging non-performing loans rocked the banking system. The reforms, which saw the worst-performing SOEs closed down or privatized, were a success: a banking crisis was averted and the pared-down SOEs posted better results in the early years of the 21st century.

Then the US investment bank Lehman Brothers tanked in September 2008, setting off the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Alarmed by the breadth of the crisis, the Chinese authorities responded with a mammoth $586 billion stimulus package.

That expansionary fiscal policy helped China escape the Great Recession relatively unscathed, but the ensuing credit explosion worsened industrial overcapacity. “The gap in return on assets was not very big in the heyday of China’s industrialization, just before the global financial crisis, but it has risen materially since then, because of continued large investment by SOEs in heavy industry at a time when demand has started to slow,” says Oxford Economics’ Kuijs.

In a February report on China’s overcapacity, the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China notes that prior to the 2008 financial crisis, Chinese producers were able to export goods to the US and Europe in overcapacity industries when domestic demand was insufficient. The report likens that strategy to “a safety valve on a pressure cooker.” Flagging demand from the US and Europe after the financial crisis made that strategy no longer feasible—at least not without provoking considerable backlash.

Over the Top

Meanwhile, local governments, flush with cash from Beijing’s rescue package, went on a construction binge. Infrastructure, housing and factories sprang up at a torrid rate, irrespective of demand. The share of investment in China’s GDP jumped to near 50% from 40% before the financial crisis. Within five years to 2014, China’s total debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 150% to 282%, the highest among all emerging-market economies.

Now the hangover from China’s construction bender is biting. To begin, resources are wasted as utilization rates fall. For instance, by 2015, China was the world’s leader in wind power capacity with more than 145 gigawatts installed. Yet many wind turbines across China have been abandoned. According to an April report in the People’s Daily, the official newspaper of China’s Communist Party, wind power plants have been ordered to run well below full capacity in Inner Mongolia (82%) Xinjiang and Jilin (68%) and Gansu (61%). China’s National Energy Administration reckons leaving the wind turbines idle has cost China RMB 16 billion ($2.47 billion).

In heavily polluting industries, the effects of overcapacity on the environment can be devastating given the enormous scale of production. In the case of steel mills, pollution remains a health risk even after the mills close because steelmakers dump toxic wastewater filled with acids and heavy metals into ponds or dry river beds. From there, it seeps into ground water and eventually sources of drinking water.

Overcapacity stymies innovation too, as cash-strapped firms have less money to invest in research and development. In its February report, the European Chamber of Commerce in China notes China’s Made in China 2025 initiative could be compromised by overcapacity. The report cites the supply glut in China’s ship-building industry as a major impediment to the government’s goal of Chinese-made high-tech ships reaching 40% of the global market by 2020.

Furthermore, the thin margins of companies in overcapacity industries means it is difficult for them to repay their loans. Gan of CKGSB estimates three-fourths of the firms in the manufacturing sector have margins below 15%. That has forced steelmakers to cut corners and costs to try to maintain profit margins. China’s major steelmakers lost RMB 53.1 billion ($8.07 billion) from January to November 2015.

As a large amount of bank lending is flowing to these capital-intensive industries, non-performing loans (NPLs) are on the rise, more than doubling in 2015 from the previous year to RMB 1.95 trillion ($296.8 billion). If NPLs continue to rise, Chinese regulators will be obliged to recapitalize the smaller and regional banks.

“It’s got to be a big worry for the Chinese authorities,” says Tim Condon, chief Asia economist of ING Bank in Singapore. To boost bank profits, “they may relax the provisioning requirement from 150% to 120%.”

Global Fallout

In some sectors, China continues to try to alleviate overcapacity by exporting goods to Europe and the US. That has unsurprisingly irked its Western trading partners. The European Union’s steel industry, which has lost 20% of its workforce since 2008, is lobbying to deny China market economy status this year as doing so would make it harder to impose tariffs on dumped Chinese steel. Beijing insists that the WTO must automatically accept China as a market economy at the end of this year because of the expiry of a provision in Article 15.

Some analysts say granting China market economy status could cost millions of jobs across the European Union. A September 2015 study by the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, DC, found that granting China market economy status would threaten 1.7 million to 3.5 million EU jobs.

Research by the Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies suggests that Chinese imports in sectors with current anti-dumping measures will rise 17% to 27%, while layoffs will be “significant” but less severe than what some industry lobbyists claim.

“We want to see solutions that work for everyone,” says Lance Noble, manager for policy and communications at the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China. He notes that just 2% of China’s trade is subject to trade remediation measures under the WTO. “That 2% is of great importance, but then there is the 98% that isn’t affected,” he adds.

For its part, the US does not seem willing to grant market economy status to China anytime soon. Experts say Washington sees it as one of the last remaining issues that provides leverage to push China to accept global economic standards.

Nor is Washington easing up on anti-dumping duties for Chinese steel. The US currently has imposed punitive tariffs on 19 categories of Chinese steel. In March, the US Department of Commerce imposed preliminary duties on Chinese cold-rolled steel imports (used in the manufacturing of auto parts and shipping containers) of 265.79%.

Damage Control

To alleviate overcapacity, Beijing announced last December that it would cut 6 million SOE jobs, including 1.3 million coal jobs and 500,000 steel jobs. The Chinese authorities estimate the cuts in the steel sector will reduce annual crude steel capacity by between 100 million and 150 million metric tons by 2020. That’s equivalent to about 13% of the existing capacity of 1.2 billion tons estimated by the China Iron & Steel Association. To cushion the blow for workers in the steel and coal sectors, China is setting up a fund worth RMB 100 billion ($15.3 billion).

Chinese policymakers “are averse to unemployment, but they can’t square that circle: they will have to swallow some job losses,” says Condon of ING. “They will try to get away with as few closures as possible.”

In a March research note, BMI Research points out 1.8 million workers comprise roughly 23.3% of overall workers in the steel and coal sectors, while the 6 million SOE workers account for just 0.7% of China’s estimated total workforce of 807 million. By contrast, about 30 million jobs were cut in the hard-hitting SOE reforms led by former Premier Zhu Rongji from 1998-2003.

“The problem is that China’s investment levels are still very high, relative to both output (value added) and current capacity,” says Kuijs of Oxford Economics. He notes that industrial capacity largely grew in line with actual industrial production (value added) until 2007. But since then, capacity has grown faster than production while demand has ebbed. “That means that, even as investment falls, capacity is still growing significantly,” he says, adding that Oxford Economics found China’s industrial capacity rose by 7.4% last year, compared to the official figure of 6%.

Additionally, BMI notes that worker “reallocations and/or retrenchments in ʻzombieʼfirms” will not address the companies’ debt travails, but only serve as compensation to those who lose their jobs. Firms must still repay their debts to avoid saddling state banks with more NPLs.

Some Chinese officials have suggested exporting China’s industrial overcapacity to countries in the developing world to build infrastructure. One of the main proponents of this scheme is Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs He Yafei, who notes ASEAN countries are projected to spend $1.5 trillion on infrastructure projects between 2011 and 2020.

Many countries may not be willing to accept high amounts of Chinese debt (lending from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank), production and labor, especially countries which have geopolitical disputes with China; in emerging Asia, they include India, Vietnam, the Philippines and to a lesser degree Malaysia and Indonesia. States willing to accept it are likely to be weaker, such as Cambodia, Laos or Pakistan, and more likely to default on their loans, notes the European Chamber.

In July 2015, Huang Libin, an official from the MIIT, said: “For us there is overcapacity, but for the countries along the ʻOne Road One Beltʼ(OBOR) route, or for other BRIC nations, they donʼt have enough and if we shift it out, it will be a win-win situation.”

No Easy Solution

Some analysts agree with Huang. In a study conducted last year, the Hong Kong-based brokerage CLSA and China Citic Bank found OBOR would enable China to export its overcapacity in steel, cement and aluminum as it created a massive new free-trade zone. “One Belt, One Road could have as much impact on China’s internal economy as it will have internationally,” wrote CLSA Head of China-HK strategy Francis Cheung and Head of China Industrial Research Alexious Lee. “China’s top priority is to stimulate the domestic economy via exports from industries with major overcapacity such as steel, cement and aluminum…. Large SOEs will lead the way, but smaller companies will follow.”

But according to David Dollar, a senior fellow in Foreign Policy, Global Economy and Development at the Brookings Institution in Washington, OBOR markets are not large enough to absorb China’s excess capacity in sufficient amounts. “In steel alone, China would need $60 billion per year of extra demand to absorb excess capacity…. The economies of Central Asia are not that large,” he wrote in a July 2015 paper.

“From an economic standpoint, China has been exporting excess capacity all along,” says Gan of CKGSB. If it were possible to boost exports in overcapacity industries to the developing world, “it certainly would help, but to rely on that as a solution [to the overcapacity problem] could be a bit of a stretch.”

She adds: “We certainly see a willingness from the authorities to address the overcapacity problem, but not a consistent set of policies.”

Why has Beijing let the problem fester? To be sure, the Chinese authorities fear the effect a massive wave of layoffs would have on social stability: They will not take that risk. But that alone does not explain the glacial pace of reform.

Rather, Chinese policymakers have hesitated to tackle overcapacity head on because to do so requires rethinking China’s model of state capitalism. As long as local governments are evaluated primarily on the basis of meeting a GDP growth target set in Beijing, they will be loath to slash industrial output.

In a 2015 report on China’s overcapacity, Ji Zhihong, Director General of the Financial Market Department at the People’s Bank of China, notes local governments eager to inflate GDP growth try “to boost investment at all costs” by keeping prices for land, water and energy artificially low while “implicitly guaranteeing loans in overcapacity industries.” That results not only in worse overcapacity, but also heavy pollution as “environmental costs are often not assessed on polluters.”

Ji urges Beijing to let markets play a larger role in resource allocation. He recommends introducing market pricing for land, water and energy, reducing or eliminating subsidies, and liberalizing interest rates to reflect the real cost of borrowing.

Yet few analysts expect this kind of drastic reform to come anytime soon. Reducing China’s industrial overcapacity “is going to be a process, not an event,” says ING’s Condon. “Chinese policymakers feel they have the fiscal wherewithal to draw it out and avoid sharp short-term pain.”

He concludes: “There is going to be burden sharing. The rest of the world is going to help China absorb the problem.”