China is strengthening its intellectual property laws much faster than many realize. Intellectual Property Rights infringement has been a longstanding issue in China, but as patent laws have developed, foreign firms are saying there are signs of progress.

In late April, China’s Ministry of Public Security launched one of the most dramatic piracy busts in its history.

Over the course of a few hours, police in the eastern city of Yangzhou rounded up a huge crime ring suspected of selling bootlegged versions of a string of hit movies, took 251 people into custody, shut down 361 websites and seized seven servers that had been used to create high-definition copies of dozens of films. A Public Security Bureau (PSB) official estimated that the pirates had cost online streaming sites and film companies $117 million in lost revenue.

The South China Morning Post called the move “an apparent bid to support [Beijing’s] claim it has tightened protection of intellectual property ahead of trade talks.” But the arrests were actually more likely part of a very different story, and were aimed not at protecting the interests of foreign movie studios, but of Chinese ones.

The bootleggers’ most popular titles were domestic blockbusters including the sci-fi hit The Wandering Earth and comedy Crazy Alien.

While China remains the world’s copycat leader, the bust indicated that China is beginning to take the protection of intellectual property rights (IPR) more seriously.

“The Chinese government has done amazing things in this area in a short space of time,” says Erick Robinson, a partner at the law firm Dunlap, Bennett & Ludwig and former Director of Patents for Qualcomm in Asia. “The rules are changing every few months.”

“The Chinese government realized that China has a market to protect,” says Robinson. “Look at Alibaba, Huawei, Tencent and Xiaomi—all these companies are doing great things and they need protection.”

Stealing the crown jewels

Chinese IPR theft has been a hot-button issue for the US at least since the time of President Bill Clinton. In 1995, the 42nd president threatened to slap 100% tariffs on $2 billion of Chinese imports unless Beijing did more to live up to its promises on stamping out IPR infringements.

But the threats had little effect, and for decades most foreign firms considered constant IPR infringements an inevitable cost of doing business in China.

In 2015, a US government commission estimated that China accounted for 87% of global counterfeit goods. The same year, the software industry alliance BSA estimated that 70% of new computer software installed in China each year was unlicensed. Multinationals were also regularly victims of IPR theft, with hackers and paid-up corporate spies keen to acquire valuable trade secrets.

“When Western companies first began to operate in China, espionage at their facilities was rampant,” says James Lewis, Senior Vice President at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and a former official at the US Department of Commerce.

Western firms in a wide variety of industries were forced to form joint ventures with local companies in order to operate in China, and many found themselves subjected to official pressure to transfer valuable technology to their new partners.

This process was facilitated by controversial policies such as the Trade Import-Export Restriction (TIER) regulation.

“Under TIER, all improvements made to a technology as part of a joint venture, even if they were fully generated by the foreign company, were owned by the domestic partner,” explains Robinson.

Foreign companies had little power to defend their interests because of the inadequacies and inherent biases of China’s legal system.

Courts were inexperienced, the rules were stacked in favor of defendants and even if a conviction was made, the penalties for IPR violations were laughably low.

“A few years ago, my advice to clients was: don’t sue a Chinese company in China,” says Robinson.

Changing mindsets

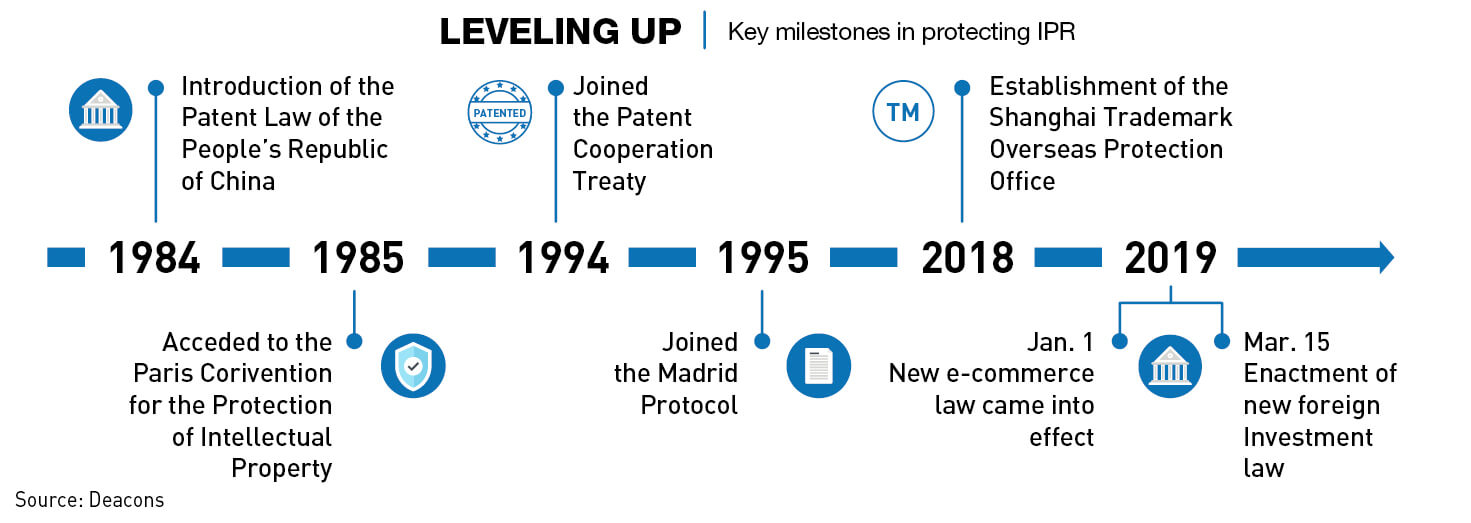

The Chinese government made promoting innovation central to its economic strategy in its 13th Five-Year Plan, published in 2014. Since then, it has made real progress in strengthening IPR protection for both domestic and foreign firms.

“Enforcement has really tightened up and laws have been changed to broaden and improve the quality of protection,” says Alice de Jonge, a senior lecturer at Monash University in Australia whose research focuses on IPR issues.

One game-changing measure has been to set up specialist IPR courts in major cities. There are now four such courts, plus another 17 smaller IPR tribunals.

The judges in these courts have been able to build up real expertise in handling IPR cases, which has led to much better outcomes, says de Jonge. “The experience gives the courts a lot more confidence to find that a breach has occurred and to calculate the proper compensation.”

In China’s legal system, cases decided by the lower courts and adopted as guiding cases by the Supreme People’s Court also have to the potential to improve the way IPR cases are handled.

Robinson cites the example of the way courts calculate loss of earnings in patent infringement cases, where a change made at the local level has led to a dramatic shift in the balance of power in Chinese courtrooms.

Defendants used to be under no obligation to hand over internal documents, such as product-by-product revenue figures, which are crucial to helping plaintiffs prove loss of earnings.

But then local courts started allowing plaintiffs to estimate losses based on publicly available data. The courts would use that figure unless the defendant provided proof that it was inaccurate.

This change in procedure has made it much easier for plaintiffs to win substantial damages.

“Damages used to be a joke in China, but my prediction is that we’ll soon see a $50 million award,” says Robinson.

Reducing risk

The stricter IPR environment is already bringing tangible benefits to foreign multinationals in China.

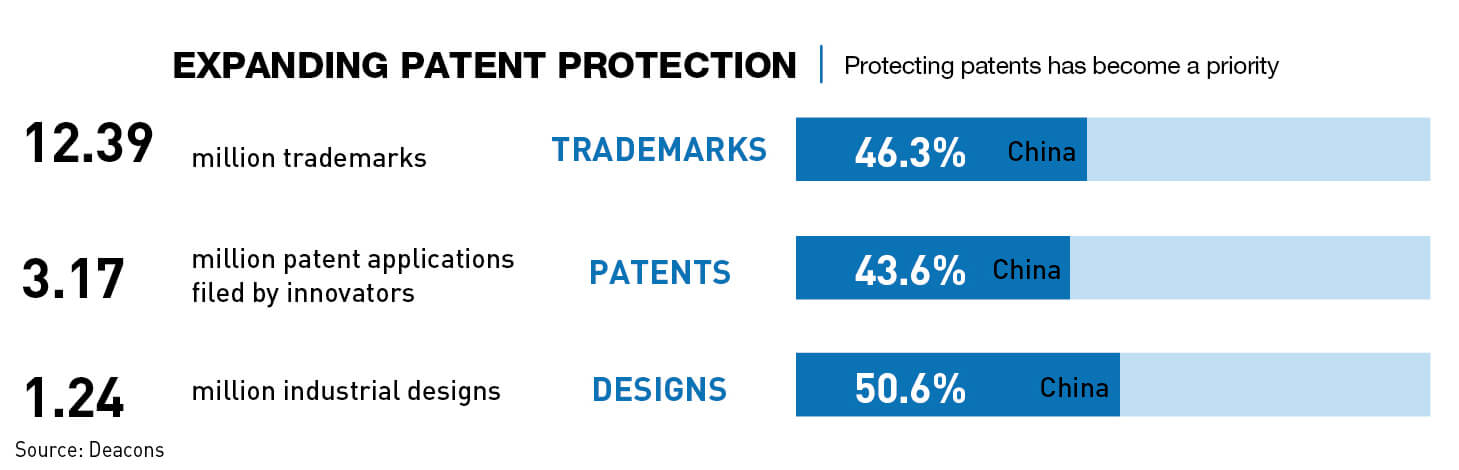

American companies received $7.2 billion in IPR royalties from Chinese enterprises in 2018, up from $3.5 billion in 2011.

Foreign firms in most industries are now less hesitant in enforcing their rights against domestic IPR violators, as most courts no longer prioritize defending the interests of local enterprises.

“No place is perfect, but if you’re a foreign company you can probably get as fair a shake in China as you could as a foreign firm in the United States,” says Robinson.

According to the law firm Rouse, foreign firms in China now have a higher win rate in patent cases than domestic firms and receive higher damages on average.

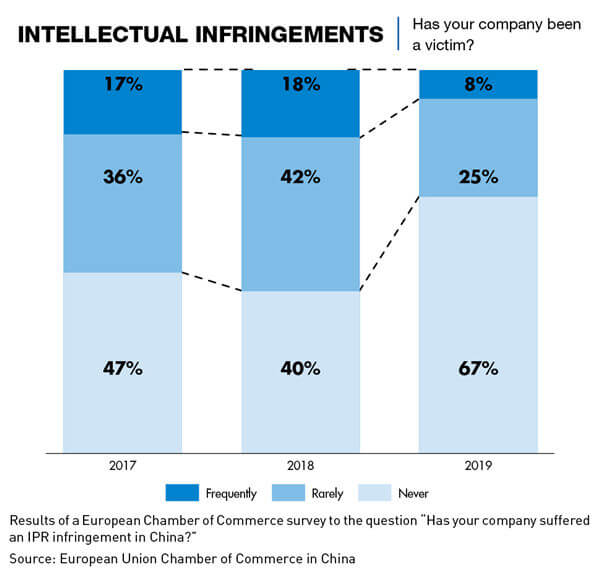

Recent surveys of foreign businesses in China also show that intellectual property protection, though still a serious problem, is less of a concern than it was a decade ago. In the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China’s 2019 member survey, 33% of European firms said that they had experienced an IPR infringement in China, down from 60% the previous year.

Fifty-nine percent of European firms now say they consider China’s IPR laws to be adequate, while 35% are satisfied with enforcement of these laws, up from just 13% in 2013.

When the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai asked its members to list their greatest operational challenges, executives placed IPR infringements seventh—far below issues such as rising costs and lack of available talent.

China vs. China

But the largest beneficiaries of the tighter IPR regime have been domestic firms, many of which now own valuable intellectual property themselves.

A spike in IPR cases occurred last year, with China’s courts accepting 41% more cases than in 2017. This was driven almost entirely by the rising number of local disputes, according to Laura Wen-Yu Young, Managing Partner of Wang & Wang, a law firm active in both Asia and North America.

In most industries, Chinese companies are now as strong as their international competitors. They have little to fear from operating inside a strict IPR regime that treats all parties equally.

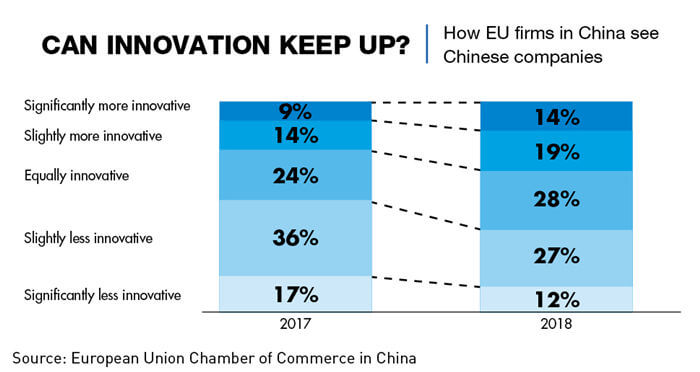

More than 60% of European companies in China now think that domestic firms are at least as innovative as foreign firms, according to the EU Chamber. More than 30% believe that Chinese companies are more innovative on average.

American firms in Shanghai now consider domestic competition their second largest business challenge, with 30% of companies agreeing that it is a “serious hindrance” to their growth. For this reason, many domestic companies largely welcome Washington’s attempts to push Beijing to speed up its IPR reform agenda.

“Chinese people continue to say that external pressure helps push the IPR development agenda along, and this helps local IPR holders as well,” says Young.

This can be seen clearly in sectors such as software and e-commerce, where Beijing has recently launched landmark reforms aimed at stamping out endemic piracy.

The US has been begging China to clean up these industries for years. But now that Beijing is finally doing so, the big winners are likely to be Chinese companies.

“The reason why they have heightened patent protection in the software space is that some of the most important and fastest growing software companies are, guess what, in China,” says Robinson.

Structural reforms

The strength of domestic firms also means that Beijing has little to lose by meeting Washington’s demands for fair treatment for foreign firms.

After trade war negotiations broke down in early May, US officials decried China’s refusal to write agreed reforms into law on certain issues. But the fact is that the Chinese government has already made legal changes that deliver on many of the US’s top demands.

The notorious TIER regulation has been abolished. Licensing rules have been simplified to give local governments less leverage over foreign firms. The definition of trade secrets theft has been broadened and the penalties for violations substantially increased. Likewise, penalties for patent violations have been hiked dramatically.

The revised Law Against Unfair Competition, meanwhile, specifically bans any form of forced technology transfer under any circumstances.

“If you look at the laws on the books in China, they are now equal to any developed country, particularly after the amendment to the Unfair Competition law,” says de Jonge.

“The trademarks and trade secrets reforms will be a big help to foreign companies, but they will also help the domestic firms,” says Robinson. “As China continues to evolve into a technology leader, these reforms will be needed.”

Straitjacket on innovation?

As IPR rules continue to strengthen in China, some have even begun to worry that the tighter rules could start to hold back innovation in the country’s dynamic technology sector.

There has been growing concern among social scientists that patents can in some cases stifle innovation. And a turn toward patent activism would be a huge culture change for China’s tech ecosystem, which for decades has been defined by its copycat culture.

For some experts, including Kai-Fu Lee, CEO of venture capital firm Sinovation Ventures and author of AI Superpowers, the rampant plagiarism among Chinese startups is one of the reasons why the tech sector has become so dynamic.

It has created an environment of ruthless competition where “gladiator” entrepreneurs like Wang Xing, founder of lifestyle super-app Meituan-Dianping, have to relentlessly tweak products and business models to stay ahead.

But China appears unlikely to replicate the problems of the United States’ patent system. The Chinese legal system more closely follows the German model than the American one.

The US system tends to favor large companies over smaller competitors because cases can run on for years and legal costs run into the millions of dollars. But in China, a patent case typically costs both parties just $250,000 to litigate and is completed within 10 months, according to IP Watchdog.

China also places more restrictions on the power of market leaders than the US because it has a much more relaxed attitude toward suits filed by non-practicing entities (NPEs).

NPEs are companies that make money by filing patent lawsuits on behalf of a small plaintiff and taking a cut of the winnings. In the US, they are often dismissed as “patent trolls,” but they can also play an important role in helping smaller players hold larger companies to account.

“If you take NPEs out of the equation, which the US largely has, then the middlemen have been removed,” explains Robinson. “It basically means that the big companies that have the money to destroy you in court, or just exhaust you, will always win.”

In fact, China’s more activist approach to IPR law is already being felt far beyond the country’s borders, as US companies with business dealings in China can also fall under the jurisdiction of Chinese courts.

China’s potential influence could be seen clearly in the recent legal battle between Apple and Qualcomm over the chipmaker’s patent royalties.

Apple looked to have the upper hand in the dispute, but Qualcomm scored an unexpected victory in December when a court in Fuzhou granted the firm two preliminary injunctions which banned Apple from selling several iPhone models in China. Tim Cook’s firm was able largely to circumvent this ban, but the decision sent shockwaves through global markets.

It is impossible to say whether the Fuzhou incident played a role in Apple’s last-minute decision to settle with Qualcomm in April, but Robinson suspects it could have been a significant factor.

“China turned out to be the great equalizer,” he says. “Apple still makes most of their stuff in China, they had just lost injunctions on two software patents and Qualcomm has around 40,000 patents that go to the heart of what makes a smartphone a smartphone.”

This case could prove to be just the beginning. For decades, China has been renowned as being the world’s number one IPR infringer. And while progress is being made, this may be the beginning of it becoming a key patent enforcer.