Will the Shanghai free trade zone live up to the hype?

“In retrospect, one of my biggest mistakes was leaving out Shanghai when we launched the four special economic zones,” Deng Xiaoping, the chief architect of China’s early economic reforms, said in 1992. The 88-year-old Chinese leader spoke those words during his “southern tour”, a trip to generate support for his plan to “open” the Chinese economy. More than 20 years later, the reforms launched by Deng and his followers have transformed China into a booming market economy. This fall, China’s new leaders sought to fulfill the rest of Deng’s wishes by setting up a special economic zone in Shanghai.

The 29-square kilometer China (Shanghai) Pilot Free Trade Zone (Shanghai FTZ) was formally launched on September 29, and a first batch of 25 Chinese and foreign companies have already been granted licenses to register in the zone. But much about how the zone will operate remains unclear. Expectations for the zone’s likely impact range from the pessimistic to the irrationally exuberant, providing a picture of China’s reform debate writ small.

The zone’s announcement was met with high expectations, as pro-reformists mused about the potential for dramatic reforms, including currency convertibility, interest rate liberalization, rule of law and tearing down the Great Firewall. But opinions subsequently swung toward the pessimistic as the government released a long list of prohibited activities for foreign companies in the zone.

The reality is somewhere in between. Analysts say the zone will initially offer limited but significant reforms to liberalize trade, open the service sector, streamline bureaucratic controls, and open the country’s financial sector. Implementation always the issue in China, authorities are likely following Deng’s famous economic reform strategy of “crossing the river by feeling the stones”—gradually trialing policies in the zone for potential nationalization.

A New Source of Growth

One of the loudest proponents of the zone has been Li Keqiang, China’s current premier. In an editorial in Financial Times, Li called for increasing the role of the private sector to sustain growth. “We can no longer afford to continue with the old model of high consumption and high investment,” he wrote. “We will explore new ways to open China to the outside world, and Shanghai’s pilot free-trade zone is a case in point.”

Li and his supporters believe that the dividends are fading from China’s current growth model, which relies on manufacturing and infrastructure investment, and they see the zone as playing an instrumental part in reinvigorating growth by helping to rebalance the economy towards consumption and services.

Chen Long, Professor of Finance at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, says falling returns on investment, inadequate funding for small and medium sized companies, and extremely high grey market interest rates have all convinced the government that it needs to reform. “What’s impressive about the free trade zone is that it reveals what the government wants, its intention for the next five to 10 years. And the point is to transform China into a society that is part of international standards,” says Chen.

Chen identifies three major areas of reform that authorities have pledged to carry out in the zone. First, the government plans to reshape the investment environment. These reforms include switching to a “negative list”—in which foreign and private companies are allowed to operate in all sectors from which they are not specifically barred—and allowing companies to set up operations through a registration system rather than lengthy government approvals, says Wang Tao, Economist at UBS Investment Research.

Secondly, the government has promised to introduce financial reforms, including relaxing controls on investment and restrictions that prevent foreigners from investing in China’s capital markets and Chinese from investing abroad. These reforms would help Shanghai meet its goal of becoming a global financial center by 2020—a goal that was looking like a dim prospect before the zone’s establishment.

Thirdly, in order to bring the investment environment up to international standards, the government has to redefine its role in the economy, Chen says. Policies state that the zone will standardize regulatory and administrative treatment for all firms, essentially leveling the playing field for state-owned, private and foreign companies.

Chen argues that these goals have become clear just in the past few months, partly as a result of China’s trade negotiations with the US. When the Shanghai zone was initially approved in July, it was meant to be a low tariff zone for trade and shipping. But since July, the zone has been upgraded into a national strategy that could potentially pave the way for China’s entry into global trade agreements, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

Talks over the TPP now encompass the US, Japan, Korea, and other countries around the Pacific Rim. Although Chinese officials initially seemed to see the TPP as a way for other countries to contain its rise, recently appear to have realized that not joining the world’s foremost economic and trade pacts could weigh heavily on China’s future growth. Joining international investment agreements means China must abide by international standards, which includes greatly curtailing the role of the government and carrying out significant domestic reforms with regards to intellectual property rights, state-owned companies, and investment.

The Shanghai zone could be instrumental in helping China carry out the necessary reforms to join the TPP, says Nicholas Borst, China Program Manager at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “If they get experience with some of these policies measures now, they can scale them up more quickly in the future.” However, Borst cautions that there are further necessary reforms not addressed in the Shanghai zone, which prelude China from the TPP.

Nay-Sayers

Not all observers are optimistic about the Shanghai FTZ’s role in meaningful reform. Announcements that the zone will not offer lower corporate tax rates, relax restrictions on foreign ownership of banks, or liberalize interest or exchange rates anytime soon have led many to curtail their expectations. The long “negative list” released by the Shanghai government, detailing 190 restrictions on foreign investment in the zone, added to the pessimism. Some critics point to the disappointing precedent of the Qianhai Special Economic Zone, an area on the mainland near Hong Kong for trialing financial reforms that has had little impact on the broader economy.

Qinwei Wang, China Economist at Capital Economics, argues that the impact of the Shanghai zone has been overplayed. “My view is that the Shanghai free trade zone will be consistent with what happened over the last couple years, of China trying to push reform forward but it happens in a more gradual way [rather] than in an aggressive way.”

The Shanghai government and proreform officials such as Li Keqiang are clearly pushing for reforms in the zone, but leftists in the government and vested interests that could see their wealth and influence curtailed with financial liberalization, such as the executives of state-owned enterprises, may be dragging their feet.

Another factor that may limit the scope of reform is the stated requirement that the changes in the zone be replicable elsewhere in the country, writes Ting Lu, China Economist for Bank of America Merrill Lynch, in a note. As a highly developed international city with strong governance and human capital, Shanghai may be ready for dramatic financial and legal reforms, but these standards will be harder to implement in China’s hinterlands.

Finally, some analysts say that financial regulators fear that liberalizing exchange and interest rates in the zone, but not elsewhere in China, would create tremendous incentives for people to make money through arbitrage and create risk for the financial system, says Wang of Capital Economics. “I think they will be very cautious, and that’s why there are so few details about the financial sector measures.”

Borst of the Peterson Institute agrees. “I think there’s just a huge concern that interest rate liberalization will lead to unhealthy competition amongst banks, potential losses for depositors, and financial instability, and that’s the last thing the government wants. They weigh that very concrete fear against the broader, more diffuse benefit of a more balanced economic model, and the more concentrated fear of a financial crisis wins out.”

Chinese economic planners may be looking to the examples like that of South Korea, which pursued an ambitious liberalization regime in the 1990s. While the international community applauded South Korea’s efforts, in the end the reforms left the country vulnerable to the Asian Financial Crisis that struck the region in 1997.

History Lessons

Wang of UBS argues that reforms to open the services sector and streamline government administration and supervision will be the most influential, since they are easiest to expand nationwide.

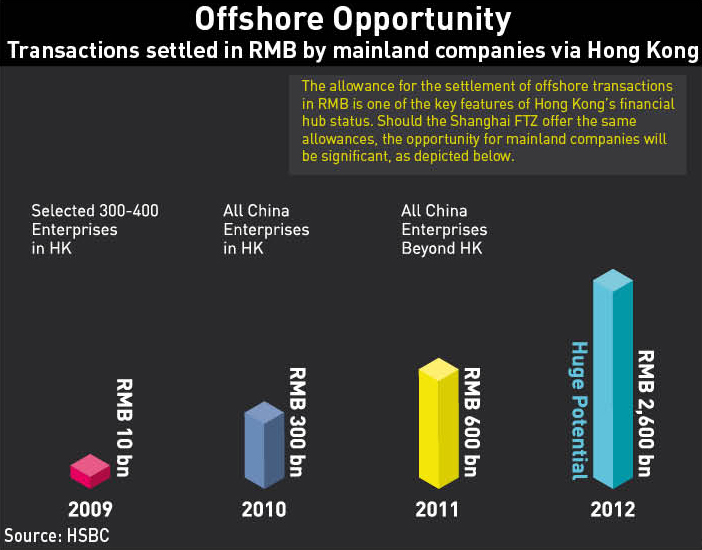

The zone’s financial reforms also look transformative, but whether they will have much of an impact on the broader country is less certain. In an announcement in December, the People’s Bank of China clarified the financial reforms that it will carry out in the zone, including allowing foreign companies in the zone to invest in Shanghai’s securities markets and Chinese companies in the zone to invest in exchanges abroad. Among other reforms, the zone will also promote cross-border financing in renminbi and foreign currencies and allow foreign financial institutions in the zone to borrow renminbi from overseas.

Money will be allowed to flow relatively freely between the zone and the outside world. However, the central bank will set up special accounts in the zone that it can monitor to control flows to the mainland. When it comes to setting up such a firewall, regulators face a tricky dilemma, says Wang of Capital Economics. A lack of an adequate firewall may lead to destabilizing capital flows. But if they strictly control capital flows, the impact of reforms in the zone could be limited—as the example of Qianhai, set up in 2010, demonstrates.

The Qianhai special economic zone was heralded as a hub for global financial services that would help internationalize China’s tightly controlled currency. Chinese companies in the zone would be allowed to receive renminbi loans from Hong Kong banks, while local private equity funds could raise renminbi capital from Hong Kong investors.

Today, these trades are taking place, but their scale has been much more limited than anticipated. One major reason is that authorities set up extremely tight firewalls between Qianhai and the rest of the mainland, such that renminbi flowing in from Hong Kong can still only be used for investment within Qianhai itself.

“Qianhai has erred way too much on the side of containing things within the zone,” says Borst. “They really just want to open a very controlled channel between Hong Kong and Qianhai, and not let too much else spill out. But the whole value of the zone is how much they let things spill out of it.” Also complicating investment is a lack of clarity on whether money will be allowed to leave Qianhai in the future, and how quickly restrictions may change.

Analysts are quick to point out that the Shanghai zone is happening on a much larger scale and with much stronger backing than Qianhai. Support at the central level is essential for implementing dramatic reforms, especially in the financial sector, says Wang of Capital Economics.

And the Shanghai zone has already developed much more quickly than Qianhai did, with regulators in charge of securities, banking, insurance and industry all releasing relevant guidelines: Shanghai “is leaps and bounds ahead,” says Borst.

Qianhai is one thing, but those who expect the Shanghai zone to compete with Hong Kong or rapidly lead to comprehensive national reforms need to curb their enthusiasm, argues Lu of Merrill Lynch. Hong Kong still benefits from transparency, the rule of law, low income taxes, and a long history and strong reputation as a financial center. Lu points out that the government has not announced a timeline for yuan convertibility, interest rate liberalization and cross-border use of the renminbi—only saying that the zone can test these policies ahead of other regions “as long as risks can be controlled”.

Window into the Mind

Many in the West argue that liberalizing a sliver of China’s economy through the Shanghai zone does not make much sense, as it opens up big opportunities for arbitrage. Looking at history, however, this is the model that Deng and other leaders consistently used to carry out economic reforms.

When China first began its switch from a planned to a market economy, leaders set up a dual-price system, in which some goods were still sold at low, state-determined prices, but excess production could be sold at market prices. That led to massive arbitrage, but it also helped liberalize the Chinese economy, against all Western predictions. The Shanghai FTZ appears to be one more step in the unconventional but effective reform path for China laid out by Deng Xiaoping.

Chen of CKGSB argues that the most interesting part of the zone is not what it can do in the short run, but that it’s an insight into the government’s longer-term goals. “With this government, it’s very clear what it wants to do,” he says. “It wants to reform China into a society that is compatible with international standards.”