China has approved five new varieties of genetically modified crops for import, highlighting the huge impact Chinese GMO restrictions have on the global agricultural sector. Is Beijing planning to relax its near-total ban on GMO?

As China and the United States tried to hammer out a deal to end the trade war through the winter and into spring, an unexpected issue arose as a key focus of negotiations: genetically modified crops.

Agricultural products have long been the backbone of America’s agricultural exports. In 2017, the US shipped $13 billion of grain to China and almost all of these products were grown from genetically modified seeds.

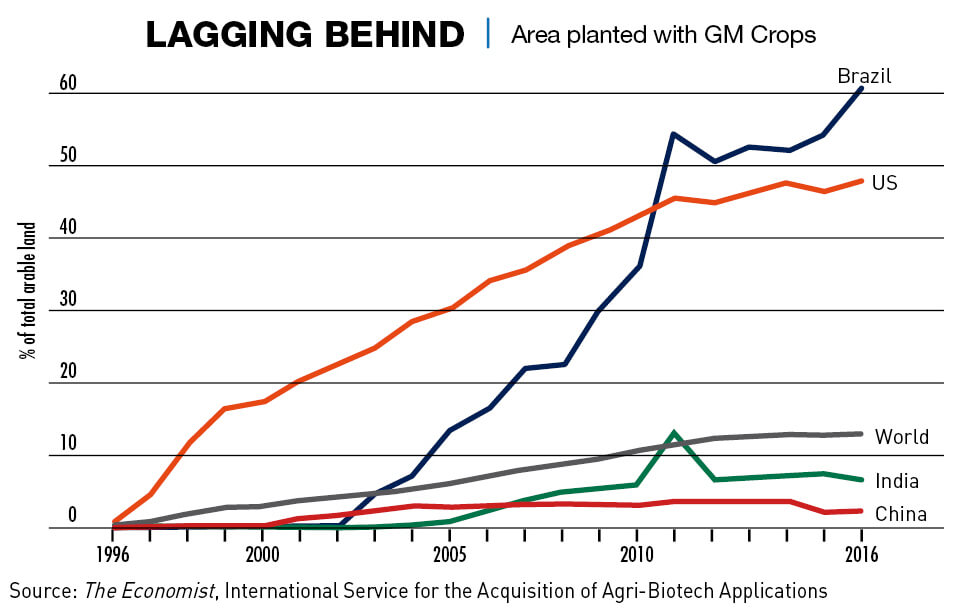

But Chinese policy toward genetically modified organisms (GMO) is much more cautious than the US, creating a continuous source of tension between the two sides.

“The GMO issue has become a hotly debated one in China, perhaps the most contested science-related debate,” says Cong Cao, a professor at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China and author of GMO China. “Given the state of public sentiment right now, the government is understandably being cautious.”

Commercial planting of transgenic crops in China is almost entirely illegal, with the exception of some strains of cotton, papaya, tomato and tobacco.

Beijing has approved imports of more than 20 types of GMO crops, which has allowed the US to emerge as a key agricultural supplier. But in recent years the government has become increasingly reluctant to grant further licenses.

The regulatory panel that decides on new import permits used to meet a minimum of three times per year, but over the past five years this has fallen to two, or sometimes just one.

This has created a problem for global agricultural technology firms, and the farmers who use their products, because China has become such an important market. Before the start of the trade war, around 60% of US soybean exports went to China each year.

It is almost impossible for global agricultural technology firms to commercialize new products until they have been approved for import by Chinese regulators.

In 2018, Swiss agtech firm Syngenta, now owned by ChemChina, was forced to pay US farmers $1.5 billion in compensation after prematurely commercializing a pest-resistant strain of corn, which led to the grain being rejected by Chinese customs.

The agtech firms argue that the slowdown in Chinese approvals has impacted innovation in GMO across the world, since firms are unwilling to invest in developing new varieties unless there is a clear path to commercialization. DowDuPont estimates that it takes 10 years and $250 million to bring a new seed product to market.

Growers have also suffered because the new seeds awaiting sign-off from Beijing would allow them to increase yields. As time passes, older GMO crops, such as Monsanto’s widely used Roundup Ready products, are becoming less effective as weeds develop a resistance to the company’s Roundup weed killer, also known as glyphosate. Agtech companies have created products with different mixes of pesticides to get around this problem—using 2,4-D and other chemicals—but Beijing has only approved a few of these new products. As a result, American farmers are largely unwilling to use them, meaning that agtech companies are losing large amounts of money.

The agtech industry body CropLife International estimated last year that the regulatory slowdown in China had cost the US economy $7 billion since 2013.

Which brings us back to the “trade war” between China and the US.

US negotiators have been pushing China to relax restrictions on GMO. They appeared to score an early victory on this front in January, when the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs announced it had cleared five varieties of GMO crops for import, including transgenic strains of canola, corn and soybeans.

These were the first approvals granted in more than 18 months. What’s more, the varieties given the green light included DowDuPont’s Enlist soybeans—a product analysts consider to have a large market potential but which had been stuck in China’s approval pipeline since 2014.

“This move looks like a signal from China’s regulators that they are willing to play ball on trade,” says Even Pay, Lead Agriculture Analyst at Beijing-based consultancy China Policy.

But US negotiators are continuing to push for further concessions. In April, one American trade official told Reuters that China’s GMO policy remained a “big issue” preventing the two sides from reaching a deal.

According to Pay, the US side is likely to have three main goals concerning GMOs in any trade negotiations. The first is an assurance that China will accelerate its approval process.

A second, more ambitious ask is the creation of a system of mutual recognition for new GMO varieties, which would mean that any seed approved by the US would automatically be eligible for export to China.

The third demand, which is the concession the US dreams of securing, is that Beijing legalizes the cultivation of genetically modified staple crops inside China. This would give American agtech firms access to sell their transgenic seeds and other GMO products in China’s vast agricultural sector, which produces around a quarter of the world’s corn and nearly 30% of its rice.

“If China were to grant approval for domestic GMO grain cultivation, it would be the fruition of more than two decades of investment by the world’s top agricultural biotechnology firms,” says Loren Puette, CEO of agriculture market consultancy China Ag. “It would greatly benefit the global agtech industry.”

How far China is willing to go on GMO policy remains to be seen. Beijing’s top priority will be avoiding any perception that it is caving to US pressure on this issue, as Chinese public opposition to GMO is intense.

But a move to relax bans on growing transgenic grains is not out of the question. In fact, there are tentative signs that Beijing is already sowing the seeds for such a policy shift.

A plot against China?

Far from being GMO-skeptic, the Chinese government has long had ambitions to lead the world in transgenic crop research. China is home to 22% of the global population but has just 8% of the world’s arable land, and so the government has been keen to promote any technology capable of boosting yields.

In 1992, China became the first country to legalize commercial planting of a GMO—a virus-resistant tobacco plant.

Since then, the government has invested billions in GMO research and development. In the 13th Five-year Plan for Science and Technology, released in 2016, GMO crop research was one of 13 strategic technologies singled out for priority promotion.

The same year, the government laid out a three-stage roadmap for legalizing the commercial use of GMO seeds. The first to be approved would be non-food crops like cotton, then would come crops mainly used for animal feed, such as corn, and then finally regulators would move on to staple foods like rice.

There is strong support inside several government departments, especially the agriculture and science and technology ministries, for allowing cultivation of more GMO crops, according to Cao.

“The government has already invested so much money into research in this area—it has an incentive to push for commercialization,” says Cao.

Yet progress towards this goal has stalled in recent years. Beijing appears unwilling to legalize domestic cultivation of GMO grain until domestic seed firms emerge capable of challenging the global agtech giants.

“Chinese-owned companies would have to profit directly from domestic GMO cultivation [for the government to consider a policy change],” says Loren Puette, CEO of agriculture market consultancy China Ag.

The government launched a crackdown on false information about the health risks of GMO in 2015, but it has been unable to stem the flood of online rumors. In December, officials were forced to deny that the agriculture ministry has a secret non-GMO food supply for its cafeteria.

According to Kai Cui, a professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, who conducted a GMO survey published in Nature, the strength of public opposition has made the government reluctant to move forward with commercializing GM grain.

“Only 18% of the Chinese population thinks GMO crops are safe to eat, 21% lower than the figure in the US,” says Kai. “And people’s reasons for opposing GMO are also different.

“In China, people worry that GMO might change their genes, and also impact the safety of their food. There are widespread conspiracy theories claiming that people in the US don’t eat GMO food, and the US just exports all its GMO crops to China.”

Point of no return

But China may be reaching the point where the government perceives a policy change less of a risk than maintaining the status quo.

For one thing, it is becoming increasingly clear that the restrictions on GMO have done little to deter farmers from seeking out transgenic seeds to boost their profits.

The exact size of China’s black market for GMO seeds is unknown, but evidence suggests that it is very large indeed. Caches of illicit seeds have been uncovered across the northern provinces, from Xinjiang in the west to Heilongjiang in the east.

A 2016 Greenpeace investigation in northeastern Liaoning province found that 93% of corn samples collected tested positive for GMO contamination.

Officials have launched several high-profile crackdowns on GMO, locking up seed distributors and farmers and burning their crops to the ground. But more incidents keep emerging.

In August 2016, for example, the local government in Jingbian, a rural county in northwestern Shaanxi province, announced it had completed an inspection of the entire region and destroyed all illicit crops. But court documents uncovered by Caixin revealed that officials uncovered dozens of metric tons of GMO corn seeds during the following months.

The continual seed scandals put the government in an awkward position. First, the images of officials burning fields of GMO crops undermine the government’s message that GMO is safe. Second, the fact that GMO are being grown illicitly means that consumers have no idea whether the food they are consuming is GMO or not.

And third, the existence of the black market sharpens the trade tensions with Washington, since US companies are missing out on large amounts of revenue.

An investigation led by Wang Deyuan of the China National Rice Research Institute found that most of the GMO corn planted in China is derived from the insect-repelling MON810 variety developed by Monsanto, now part of German conglomerate Bayer.

According to Wang, the Monsanto seed is entering the Chinese market through two main channels: by breeding it from GMO corn found in imported animal feed, or by smuggling it directly from the US.

Pushing back

The big question is how Beijing will choose to respond to this situation. Early signs suggest that the government is generally lying low. This year’s Number One Document, Beijing’s annual list of priorities for agricultural policy, gave little away on potential GMO reforms.

Some provincial governments, including Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia and Shandong, have launched fresh crackdowns on GMO seed dealers in an attempt to reassure the public.

But the Science and Technology Daily, the official publication of the Ministry of Science and Technology, has been taking a more bullish line. In July, the paper published a report arguing that farmers use illegal seeds because they “love” GMO and that the government should wipe out the illicit seed trade by simply legalizing commercial planting of GMO corn.

The message the ministry appears to be sending is that Beijing has now succeeded in preparing its domestic seed producers to compete internationally. In other words, conservatives’ worries that GMO legalization would lead to American companies dominating the Chinese market are no longer valid.

Beijing has made intense efforts to make its seed industry more competitive, consolidating a number of small producers, promoting partnerships with state-run research centers and encouraging firms to acquire global intellectual property rights.

In 2016, state-run chemicals conglomerate ChemChina acquired Syngenta, one of the world’s top GMO seed producers, for $43 billion—one of the largest corporate acquisitions ever made by a Chinese company. This has allowed China to create its own vertically integrated seed and agrochemicals giant to rival Bayer and DowDuPont.

According to Pay of China Policy, the ban on domestic cultivation is actively holding back Chinese firms.

“A lot of Chinese companies are already set up to be globally competitive,” says Pay. “In order to do that, the easiest way is to have a market at home.”

Next steps

Where Beijing chooses to go from here is likely to depend mainly on political calculations by China’s top leaders.

“Ultimately, the decision [over commercialization] lies with the State Council and everyone will have to do what the top leaders say,” says Cao.

According to Kai, the moment may be too sensitive for any bold moves on GMO.

“There are other things that the government needs to pay attention to: the economic slowdown, the China-US trade war, the problems in the financial and real estate markets—those are emergencies,” says Kai. “So, if you’re the leader of China, you’re in no hurry to approve GMO.”

For Puette of China Ag, any reforms are more likely to come next year. “ChemChina is still integrating Syngenta, while ChemChina itself is likely to be merged with SinoChem in the coming months,” Puette points out. “The corporate landscape has to settle somewhat before such a large endeavor can take place.”

Pay agrees that there are signs of momentum toward a policy change further down the line. In February, the government announced plans to open a new GMO research base in Heilongjiang, China’s northmost province, the first such facility to be built in a major grain-producing region.

“There has never really been a break in refining and improving the regulations that would enable commercialization eventually,” says Pay. “The more these research initiatives see investment and expansion, the more I think it’s only a matter of time.”

China’s research community, however, appears tired of waiting. At a seed industry meeting in July, Liu Yaoguang, a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, summed up the mood well.

“If China waits until the entire general public accepts GMO to commercialize them, that day will never come,” Liu said.