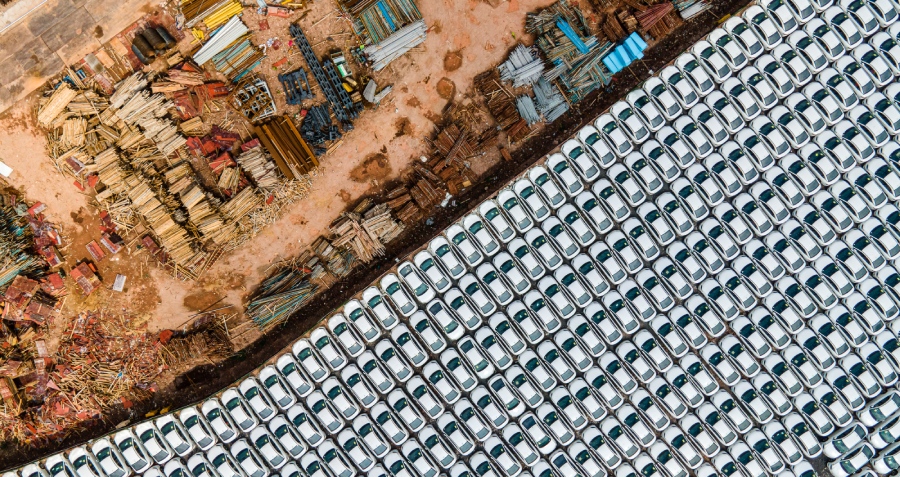

China’s ability to manufacture goods is unmatched but it appears clear that domestic and global demand is struggling to keep up. Dairy farms are having to ditch unsold milk, 70,000 China-made EVs are clogging Brazilian ports waiting to be sold and China is littered with empty apartments that have not yet found buyers.

The strength and scale of China’s manufacturing ecosystem, particularly now that digitalization of production is ubiquitous, has been a boon for the global economy, but continuing weak domestic demand has created indications of industry overcapacity across a wide range of sectors.

“There is a significant gap between Chinese production and domestic demand, that is a certainty,” says Scott Kennedy, senior adviser and Trustee Chair in Chinese Business and Economics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). “China produces around 30% of the world’s manufactured goods and consumes only around 18%. That’s a big difference.”

Rates of change

China’s increase in material output since the country’s accession to the WTO in 2001 has been meteoric. According to the World Bank, China’s manufacturing output in 2023 was worth $4.658 trillion, up from $625.22 billion in 2004. Over the same period, exports have risen from $607.36 billion to $3.513 trillion.

The WTO does not have a specific definition for overcapacity, but the concept is usually understood as product capacity that cannot be absorbed by domestic demand, which in turn usually leads to an increase in exports, often with prices subsidized. Capacity indeed does play a role, although the core problem is overproduction beyond market demand, regardless of the capacity available.

The manufacturing capacity utilization rate is also a key indicator used by economists to assess for signs of overproduction. “Things don’t look too terrible in terms of overall capacity utilization, which is currently at a pretty normal level for China,” says Julian Evans-Pritchard, Head of China Economics at Capital Economics. “When people talk about overcapacity, they tend to mean in a broader sense. It’s not just that there is too much capacity and that utilization rates are low, it’s also being used to refer to excess production, so production above the levels that the market would normally allow in a free market system.”

And it is excess production that is the key worry for both China’s economy and its international trading partners. China’s trade surplus reached a record $992.2 billion in 2024 after the country’s exports grew 5.9% and imports grew just 1.1% year-on-year. China’s continued subsidization of a wide range of industries, utilizing tax breaks and other incentives, is well documented, and the country’s increasing focus on self-sufficiency has only bolstered investment in sectors deemed national strategic priorities, regardless of demand.

The psychology of the system is less based on free-market economics and more focused on short-termism and market control, often ignoring the commercial viability of projects. “There are certain sectors that the Chinese government sees as national strategic priorities, and in those sectors, companies tend to respond to the signal from the government for investment in production,” says Yanmei Xie, geopolitics analyst at Gavekal Research. “They are, therefore, less sensitive to demand signals, and that tends to be a recipe for overcapacity.”

The excess production that results from this approach to industrial policy, and the deflationary impact that it can cause, is at the heart of the problem.

“My concern is that if inflation continues to fall, you’ll get a negative feedback loop where falling prices result in weaker wage growth, which then results in weaker domestic demand, which in turn makes the overcapacity situation even worse,” says Evans-Pritchard. “China needs to be careful it doesn’t enter a negative deflationary spiral.”

China has pushed back on overcapacity claims, with leader Xi Jinping stating in May last year that there is no such thing as “China’s overcapacity.” Liao Min, Vice Minister of Finance, also stated in July that Chinese manufacturing capacity is helping the world fight climate change and contain inflation. He pointed specifically to the fact that global demand for EVs will reach 45-75 million units by 2030, far exceeding current capacity.

“I should say that overcapacity, in a way, is a feature and not a bug of industrial policy,” adds Xie. “It can stimulate competition, and those companies that survive the resulting price wars become fiercely efficient and competitive, among other things.”

Feeling the pressure

From a baseline economic perspective, the impact of overcapacity and overproduction in the domestic market comes at the cost of inefficient resource allocation.

Still, China’s approach to managing its economy has always been relatively inefficient when compared to other more free-market-oriented economies.

For producers, the competition created by the dual threat of reduced domestic demand and excess capacity can result in price squeezes, such as the current price war in the auto industry, and is tough on bottom lines.

“Producers are facing cutthroat competition from all directions,” says Kennedy. “They have borrowed immense amounts of credit which they’re having difficulty repaying. Lower prices to remain competitive is leading to deflation, which means less income for businesses. It’s also affecting local governments around China, many of whom have backed some of these companies and are now seeing reduced tax receipts and significant shortfalls in their position.”

Additionally, government stimulus measures and the reluctance to allow companies to go bankrupt in the traditional sense mean that overcapacity in China tends to linger.

On the other hand, lower prices should theoretically be a positive for consumers, but domestic demand remains depressed for several reasons, including the property sector downturn and a general macro-economic weakness that has resulted in slower income growth. “People feel they have fewer assets because their property prices have been declining, and they feel less certain about their future earning potential, so they are less likely to spend,” says Xie.

Trade, tensions and tariffs

Given the issues at home, the natural approach to offsetting the problem of overproduction amid low domestic demand is to increase focus on exports, and this contributed to China’s record trade surplus last year.

International markets, either those that want to avoid de-industrialization or that are seeking to industrialize in the first place, are beginning to realize the impact of ballooning Chinese exports. And many are starting to impose controls and tariffs on Chinese goods.

The US is a prime example, with the country now very much in the mindset that further de-industrialization is not just an economic, political and socio-economic issue, but also a national security problem. The Biden administration had implemented tariffs on imports across several sectors, including the photo-voltaic solar sector where there is a significant amount of excess production in China, and the Trump administration has just announced 10% additional tariffs on Chinese imports. There has also been a similar response from the EU, with the introduction of tariffs on EV imports as well as several anti-dumping investigations into Chinese goods.

Given the current state of the China-US relationship, it is no surprise that the US’ trade partners are leaning towards greater controls on Chinese imports. But there are also countries with a greater geopolitical alignment with China which have begun to install trade safeguards.

“It has mostly been developed economies responding, but we have started to see emerging economies such as India and Brazil follow suit with higher tariffs on Chinese steel,” says Evans-Pritchard. “It is noteworthy that Brazil, given its closer relationship with China, will not necessarily sit back and allow Chinese firms to compete too aggressively with their domestic industries.”

Finding equilibrium

Although they don’t use the word overcapacity explicitly, China’s leadership appears to be aware of the issue, listing ‘involution’-style competition as the top priority to be dealt with in 2025 at the Central Economic Work Conference in December. The concept refers to the deterioration of a system due to intense competition and skewed resource distribution, and arguably has overcapacity at its center.

“The central government’s view is that the problem lies with local governments offering preferential policies to attract manufacturing to localities and engaging in protectionism, which in turn creates waste,” says Evans-Pritchard. “As a result, they have tried to limit that, as well as try to create a more unified national market in the hopes of reducing duplicate investments.”

This, along with the various market stimulus measures introduced since September aimed at increasing market confidence and investment, will help to some degree, but the bigger issue is that China’s quantitative supply-side approach to its economic problems does not address the macro-level imbalance between consumption and investment.

“Domestic demand and consumption have to be a much more central part of Chinese growth going forward, and it does seem like this message has gotten through,” says Kennedy. “The biggest shift will have to be in developing and implementing policies and putting the funds and regulatory support behind them, to shore up the ability of Chinese households to consume. This includes better healthcare and education, higher wages and better overall support relative to that which goes to Chinese producers. It’s a humongous challenge.”

Reaching capacity

The rise of market protectionism around the world means that simply increasing exports will not help China deal with the fallout from its overproduction. But until market demand becomes a more important factor, change will likely be slow. And the traditional supply-side, investment-driven approach to issues has only limited impact on the dearth of domestic demand and consumption that is at the heart of China’s excess capacity.

“There may be a turning point where policymakers change their approach and embrace more substantial consumption support, and the catalyst would probably be them becoming more worried about deflation,” says Evans-Pritchard. “At the moment they seem to be prioritizing national security and concentrating on reducing overseas reliance for goods, but at some point in the next five to 10 years deflation will hit a level where they have to switch tack and take more aggressive steps to address the problem.”

But for now, exports as a solution will become increasingly unviable.

“US tariffs are going to make it harder for manufacturers to offload excess production overseas,” says Evans-Pritchard. “There are obviously alternative markets to export to, but they are already shipping as much as they can to non-US countries, so it will be hard to fill the hole left by weaker US demand without cutting export prices even more.”