China’s public healthcare system is ill-equipped to handle growing demand. On the other hand, private healthcare in China is not an easy field to play in due to several reasons. Will investment sentiment survive in the country’s beleaguered healthcare sector?

It’s a typical scene in Subei People’s Hospital in Yangzhou, a third-tier city in China’s coastal province of Jiangsu. Patients that have been waiting dutifully for reception to open since 7am file in to pay for face-time with a reputable doctor. Once registered, the patients embark on a ping-pong like journey from cashier to doctor’s office, back to cashier, to laboratory, back to doctor’s office, back to cashier and finally to the pharmacy. Some patients tenuously carry their own ‘specimen’ in shallow plastic trays, collected in the centrally located restrooms which are without soap for washing up after said specimen collection. In the second doctor’s consultation the patient’s peers anxiously queue near the door waiting for the doctor’s comments, often listening in on other consultations in the process. Consultations last an average of five minutes in China, compared to more than 20 minutes in the US.

There are many facets to public hospital care in China that could rankle developed-country sensibilities: sanitation issues, lack of privacy, over-crowding and whirlwind doctor decisions, plus a strong likelihood to walk away with saddle bags of unnecessary medicine. But this is the system that Chinese people, regardless of income level, overwhelmingly trust, more than the private hospitals and clinics that are sprouting up around the country.

“I don’t trust private clinics,” says 27-year-old Ye Gen, a translator based in Shanghai. “In the past I’ve left [those clinics] with a feeling of being sold to, and not really cared for by the doctor,” she says, adding that one clinic was still sending her text message advertisements long after the appointment.

But everyone from the government to investment firms also agrees that China’s public healthcare infrastructure is unable to meet demands, especially from the increasingly affluent middle class and rapidly aging population. China’s leadership declared support for more private investment in the healthcare sector last December, and removed healthcare from the list of restricted investment sectors.

“For the first time there’s a reference to the healthcare sector as an industry, the thinking here, because historically it’s been viewed as a social sector,” says Murali Gangadharan, Head of Research at PricewaterhouseCoopers in Shanghai and co-author of a 2013 report on private healthcare investment in China.

Some private healthcare service provider firms are responding to the official green light and braving a healthcare terrain textured with inhospitable regulations, wary consumers, and doctors deeply ensconced in the nation’s top class of public hospitals. These firms all believe that in the long term, the severe demand for more healthcare options will turn into a healthy business model.

Welcome to the Jungle

Healthcare companies, both foreign and local, are still largely analyzing the market, discovering the holes in the public healthcare system and how to fill them.

China’s healthcare sector consists of three kinds of providers—public hospitals of varying sizes, domestically-owned private hospitals and clinics, and foreign hospitals and clinics, either through joint ventures or full ownership.

For decades, China’s population has funneled into the country’s large public hospitals wherever available. The top of the top are usually associated with renowned universities, such as Peking University in Beijing or Fudan University in Shanghai.

The system is in many ways inadequate in serving the public’s needs. Earlier this year, there was wide media coverage of a man dying of a brain hemorrhage after waiting 90 minutes for an ambulance in Shanghai. In some second and third-tier cities there is only one general hospital serving more than half a million residents, making it overstretched even when the hospital is in top condition, which is rarely the case.

One reason for the public’s reliance on large public hospitals is their monopoly on the nation’s best doctors. Unlike in other markets, Chinese doctors typically only find career advancement through the sponsorship of public hospitals. Prestige, political benefits and renown are career aspirations that only public hospitals can facilitate, and the larger the better.

“These doctors in the public system, beyond compensation, there is a lot that they get, they are essentially civil servants,” says Gangadharan. “In China, the hospitals do have control over essentially credentialing a physician…so you as a physician can’t just go out and start your own practice, the hospital is the entity that grants the license to practice.”

Accordingly, what Gangadharan refers to as “step-down” care facilities, or what US patients would call their primary care physician’s practice, is something private investors should consider.

“I think that’s an area of opportunity for private investors to come in and really grow this outpatient setting,” he says.

The two main challenges to such expansion are one, enticing doctors to work in private settings and two, the general lack of trust among consumers in private facilities.

“The more fundamental issue is that patient-doctor trust at the most basic level has been decimated,” says Clancey Houston, Executive Vice President of Chinaco Healthcare (CHC), a China-based healthcare provider founded by the Frist family of HCA Healthcare, operators of one of the largest hospital and clinic chains in the US.

The trust issue is largely traced back to doctors’ pay. In 2011, newly certified doctors made an average of RMB 2,000 per month, according to the China Medical Doctor’s Association, which also reported that the majority of the surveyed doctors were “dissatisfied” with pay and working conditions. In light of several recent high-profile cases of patients stabbing doctors, it is very likely these attitudes persist.

Mistrust of doctors is not without a basis in China. Many doctors have supplemented their low salaries with bribes from patients and over-prescribing unnecessary medications and treatments to generate revenue, and possibly kickbacks from pharmaceutical firms. Chinese authorities last year accused British pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline of bribing doctors in exchange for prescribing their products. Meanwhile, hospitals typically reward doctors with bonuses based on volume of patients and usage of facilities. So in the absence of a reasonable salary, many doctors in China effectively become corrupt drug pushers.

Seth Yu, Chief Administrative Officer for CHC and son of two doctors, explains that the attitude of patients exacerbates the problem. “If they just hear ‘go home and drink more water’, the patients aren’t feeling comfortable, they expect more, it becomes a really bad cycle. They think ‘you have to treat me seriously, do something on me’,” explains Yu.

Pilot reform schemes are underway in a number of public hospitals, such as in a performance-based pay study taking place in Ningxia Province, and the higher consulting fees and corresponding doctor salaries in Beijing’s Friendship Hospital. A seemingly viable alternative is the expansion of private facilities that pay doctors higher salaries, such as in the US-headquartered United Family Healthcare hospitals in China, but the doctors’ mentality that exiting the public hospital system means professional suicide limits the potential of that expansion.

But even if physician recruitment were easier, the rash of egregious profit-boosting activities of some, largely local, private facilities have left consumers largely opposed to non-public healthcare providers. There have been reports of clinics falsifying lab results in order to sell expensive treatments to the patient, going so far as to perform unnecessary heart surgery. These reports have created a serious branding problem for new private ventures.

From the perspective of foreign healthcare operators, China should be a golden opportunity. They are interested in the China market, and the government wants them to bring in their technology and best practices. But the challenges typify just where official support is falling short of real change.

Water, Water Everywhere

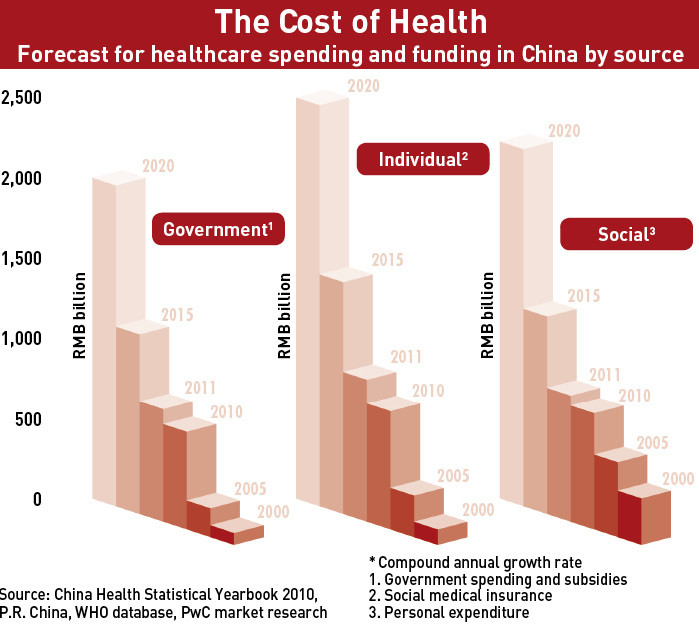

The opportunities mainly involve the increasingly affluent upper-middle class above 40 years of age. They are spending more on healthcare (see The Cost of Health) with a projected 12.9% increase in individual healthcare spending by the year 2020, reaching roughly RMB 2 trillion, according to a 2013 report from PricewaterhouseCoopers. Increased healthcare expenditure should in theory make for healthy business models.

“The climate for senior services in China is very good,” says Michael Li, Executive Director of Cascade Healthcare, which has two senior housing facilities in Shanghai. “The ground is very fertile.” Li refers to local government interest and an all-but-complete absence of transitional facilities for seniors. “China doesn’t have a true sense of a nursing home or skilled nursing facilities, there’s no senior living industry at all.”

Foreign-owned hospitals or clinics can play a role, and can do so more efficiently, in what Murali refers to as “step-down care”, care that can easily be administered by a nurse or other similarly certified professional in a more dressed-down setting than a public hospital. This may include post-surgery physical rehabilitation, clinical monitoring of progressive conditions like Alzheimer’s and dementia, or orthopedic care. The ideal arrangement would be the establishment of a referral system between the local public hospital and various categories of step-down care facilities.

“I’m not competing with the hospitals, I’m helping them, they don’t quite get that yet,” says Li, who says doctors are routinely skeptical of referring their patients to the care of a facility like Cascade, even while the option of returning home may prove more detrimental to a patient’s health.

Doctors at large tertiary public hospitals are as unsupportive of private facilities as their patients, and given that the profit structure of public hospitals is partially based on the volume of patient throughput, the inherent competition between public hospitals and step-down care facilities has resulted in virtually zero referrals.

“Public hospitals are actually afforded very little incentive to actually give a referral to an outpatient clinic,” says PwC’s Gangadharan. “Sometimes the doctors are set up in contracts that incentivize them into not doing external referrals but doing referrals within their hospital or within their clinic chain.”

But there is hope. A marketing associate for a prominent American orthopedic hospital in Shanghai, who prefers not to be named, says that they invite public hospital doctors to seminars his employer hosts to discuss the latest advances in orthopedic care, and in turn the doctors refer patients. Technology transfer is highly sought-after in public hospitals in urban centers. So while ‘seminars’ may seem like a soft reward for patient referrals, they do in fact fulfill certain requirements of the hospitals.

The other option is to recruit doctors from abroad and brand them as ‘the best in the business’, the only issue here being providing them with compensation on par with what they would earn at home. In the case of the Shanghai-based American clinic, they operate a revolving door of ‘visiting physicians’ whereby doctors take turns serving short stints, and are also stakeholders in the clinic.

The last serious impediment is payment. The national health insurance is the primary factor determining where patients seek their care. Public hospitals are generally permitted to reserve 10% of services for premium health insurance, or private plans that patients purchase to enjoy a VIP experience at renowned hospitals.

“There needs to be incentive to get the private insurance to become an alternative or a supplementary option to a whole range of people,” says Gangadharan. “If that happens you can have private sector healthcare for profit operating, you can [also] have non-profit sector with private investment, but with investors being able to get some return out of it.”

Gangadharan explains that even Chinese consumers who opt to purchase private health insurance are mainly looking to be treated in public hospitals, instead of exploring care from for-profit facilities. “Public hospitals are struggling to figure out how to expand their services to more than 10% without upsetting the notion of their being public hospitals,” he says.

Overall, the healthcare terrain is teeming with demand for solutions to the overcrowded public hospitals and their overworked doctors. But the lack of referrals, the inability to pull doctors away from public hospitals, a lack of alternative payment options and a crisis of confidence on the part of the patients is making it difficult to crack the market’s potential.

Pioneer Providers

Many companies agree they are involved in a necessary, albeit tedious, market development process. Those already in the market are the guinea pigs, stubbornly gnawing their way through the brambles so the system may become more hospitable to other companies in the future.

“It’s just a pity we have to be the ones suffering through this,” says Li of Cascade. “If you really look at the financials, we’re fools to come in at this point.”

But Li says that at this point positioning is key, positioning a company to be ready for the private healthcare expansion that most view as inevitable.

There are various frameworks that foreign companies are using to take advantage of healthcare growth in China. One of the best-known ventures involves Chindex, the China arm of US-based health insurance company United Healthcare. In addition to its high-end hospitals in China’s main cities, the company can also source management and equipment needs.

Using this model, Chindex has been pretty successful. The Beijing-based company reported a 16.3% increase in revenue from healthcare services (as opposed to equipment) in 2013 from the same period in 2012, bringing in $43.1 billion. And yet, Chindex announced in February that a consortium of private equity firm TPG and Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical would acquire Chindex and take it private.

Gangadharan says that as long as Chindex targets primarily the high-end consumers, their long-term growth is limited.

Another viable model is to pursue only management contracts, given the lower upfront capital investment requirements and the central government’s preference for building up existing public hospitals.

“You don’t need as much capital, that’s an interesting way in which the private sector can come in,” Gangadharan says. “That is essentially a trusty model.”

Gangadharan cites Beijing-based Phoenix Healthcare Group as an example, which as of June 2013 operated 11 general hospitals and 28 community clinics in China, and has begun raising funds prior to a planned IPO in October.

The most concerted investment comes in the form of direct partnership with local governments at the municipal and county level, the chosen path of Chinaco (CHC).

In 2008, the HCA Healthcare founding family, that of Dr. Thomas Frist, started to look to China for expansion and began talks with the government of Cixi, a town in China’s southeast Zhejiang Province. The Cixi government wanted to overhaul the city’s 2nd People’s Hospital. CHC presented its proposal, and five years later a new joint venture hospital is due to open this June.

“It’s become an increasingly important metric for provincial or even county level government to take responsibility for making sure their population is healthier,” says CHC’s Houston.

Good local government relationships are paramount for joint-ventures in healthcare, but this direct partnership whereby a non-Chinese company specializing in for-profit healthcare facilities is partnering directly with a government to “replace” a public hospital, is quite novel.

But importing best practices isn’t without its own complications. One is the implementation of Joint Commission Accreditation standards. The Joint Commission is a US-based agency that accredits hospitals that meet the requirements necessary to effectively administer healthcare. There is also an international version of the accreditation known simply as Joint Commission International (JCI).

“JCI has very strict requirements, for the time being, it’s very difficult for local staff to reach,” says CHC’s Yu.

Building a community’s flagship hospital won’t see pay-off for 10-15 years, says Yu. But it has the unusual benefit of an automatic supply of patients and doctors that will transfer from the old 2nd People’s Hospital to the new one. CHC is also taking the unusual road of accepting all kinds of insurance, from expensive private policies to the national insurance plan. The profit margin that hospitals can make off of patients using the government-provided health insurance is extremely slim. That’s why the more specialized private clinics are refusing the national insurance altogether.

“We wouldn’t accept the national insurance even if we could because we’d make no money from those patients, we’re not targeting 99% of the population,” says the marketing director for the Shanghai-based American clinic.

But Houston and Yu are confident that down the line they can partially recover expenses through supply chain optimization and higher efficiency. Of course having a cash-rich local government on your side is also handy. So if you haven’t hit the mother-lode, as CHC has in its municipal partnership in China’s under-ser-viced lower-tier cities, then you’re back to catering only to the affluent and their parents.

Age Before Wisdom

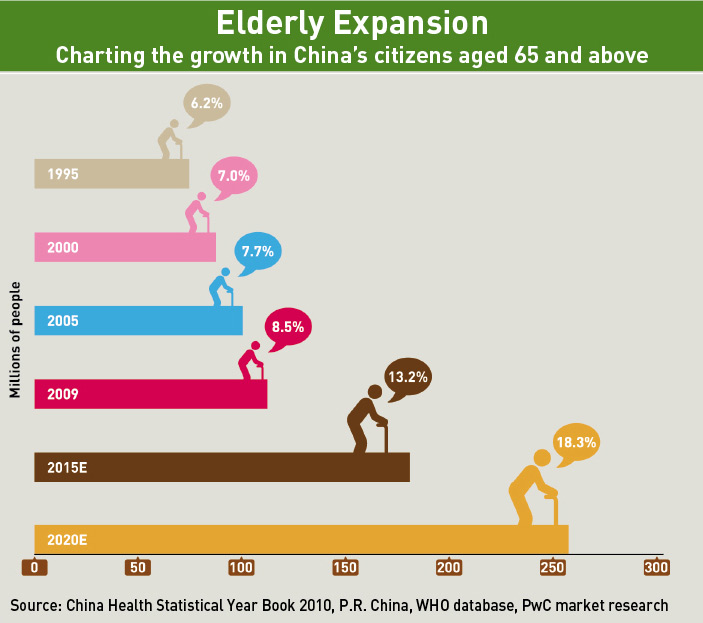

By 2053, the number of China’s senior citizens is expected to grow to 487 million people, or 35% of the population, compared to just over 12% now, according to the China National Committee on Aging.

Jim Moore is the founder of Moore Diversified Services Inc. (MDS), a US-based consultancy in senior care, and handles market research for China entry in the field of senior housing and acute senior care facilities. He says that the adult children of aging parents are waking up to the shortcomings of traditional parental care methods, and are now ready to spend to deal with the problem.

“We’re finding the same trends that we see in the US gradually evolving [in China], in that the adult child is busy, is employed, is fewer in number, and the acuity level of the aging parent is such that the housekeeper that they used to use and trust is not always able to keep up with the increasing needs of the seniors,” says Moore.

As a result, families increasingly see the benefits of what are called ‘nursing homes’ in the US, this channel for private investment, both from within and outside of China, becomes increasingly attractive. The initial start-up costs are less than for hospitals since the equipment and personnel requirements are lower, and the pool of patients can only grow.

According to Jim Biggs, the Managing Director of Honghui Senior Housing Management Consulting, if you can’t raise a facility within a five-mile radius of your target patient pool, don’t bother. As a result, senior care developments are heavily skewed towards urban centers, which means more expensive land.

“Right now the land is so expensive, the numbers don’t pencil out, that’s the paradox,” says Biggs. “Until the government says, ‘hey we need to fix this, we need to give what land we have, we need to make [land] available for the seniors in these locations where the seniors want to live,’ until that happens, we’re all kind of just chasing ourselves.” Biggs explains that there must be local government buy-in for a senior housing business model to really fly in China’s urban centers.

Ventures and Gains

Most researchers and industry insiders agree that China’s healthcare privatization is still in the experimental phase as far as private investors are concerned. It’s a guess and check system: build, publicize, educate, wait and assess. But one thing about healthcare investors in China is that they seem to be aware that they’re not going to get an instant return.

The strategy is for companies to establish themselves as early birds in the game, giving them a chance to play a significant role in what many believe to be China’s coming healthcare revolution. It’s all about establishing position.

Chindex is doing well in their targeting of high-end customers, but still fall short of the “Holy Grail” of the middle or upper-middle income market, says PwC’s Gangadharan.

CHC is blazing a trail through officialdom by meeting the government where their needs are, which they can leverage to re-create the successful chain of their US counterpart. And the smaller ventures that cater to the wealthy Chinese and expatriates will persist, but the real impact will be in vertical integration with already established public healthcare systems.

“Either we wait for the ecosystem to be mature and favorable to us, or we have to create our own minor ecosystem, but creating your own ecosystem is easier said than done,” says Li, who readily acknowledges that now is the time to push against the bureaucratic limitations of the regulators so that investment can flow more freely in the future. “Until folks like us [are] coming in, running into these problems, raising those issues and pressing the government to change, why would they change?”