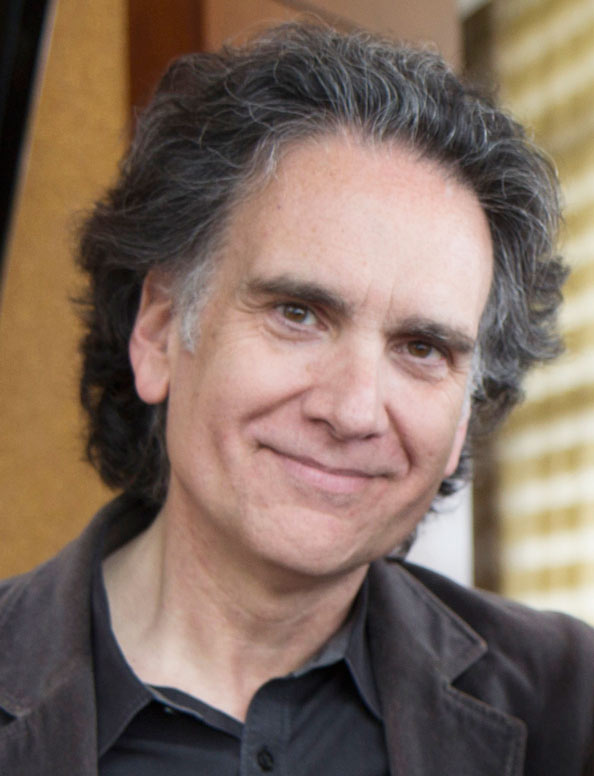

Peter Buffett, son of legendary investor Warren Buffett and co-Chairman of the NoVo Foundation, explains what is wrong with philanthropy.

Peter Buffett, the youngest son of legendary investor Warren Buffett, has rather strong views on philanthropy. In July 2013, Buffett, who is a musician, author and philanthropist all rolled into one, stirred a hornet’s nest by publishing an Op-Ed column in The New York Times, wherein he accused philanthropy of failing to address the inequalities and social problems in society.

Titled ‘The Charitable-Industrial Complex’, the article said: “As more lives and communities are destroyed by the system that creates vast amounts of wealth for the few, the more heroic it sounds to ‘give back.’ It’s what I would call ‘conscience laundering’—feeling better about accumulating more than any one person could possibly need to live on by sprinkling a little around as an act of charity.” He goes on to say that this does nothing but keep the “existing structure of inequality in place”.

Buffett, who himself runs a philanthropic organization called the NoVo Foundation, accuses otherwise well-meaning do-gooders of promoting and further exacerbating what he calls ‘Philanthropic Colonialism’: philanthropists transplanting what they think is the right solution to a given problem with scant regard to local realities, culture or societal norms.

His column sparked strong reactions and people questioned the validity of his ideas, accusing him of “an astonishing lack of understanding of both economics and of the extremity of global poverty”. It became what CNBC called, “the biggest debate over philanthropy in years—probably the biggest since Warren Buffett and Bill Gates launched the Giving Pledge in 2010”.

So what really is wrong with philanthropy? We posed that question to Buffett, who is the co-Chairman of the NoVo Foundation, to understand where he is coming from. Read on:

Q. You have been talking about an idea you call ‘Philanthropic Colonialism’. What does it mean? And where—and why—did good-intentioned philanthropy go wrong?

A. When I wrote The New York Times opinion piece, which I think suddenly made my views much more well-known to a lot of people, I mentioned this term ‘Philanthropic Colonialism’. I am sort of a student, musically, of American Indian culture. I learnt a lot about the American Indian culture. I could see both in that respect and others that often people would assume that they knew the best of what somebody else should be doing or what they needed. So in the philanthropic world, what I [see] often when I go to other countries or even hear stories in other places, I hear people saying, “Well, if they just have what we had”, or “I know this would be the best for them”, or all these ideas that are coming from one cultural reference to another without thinking that maybe it is different because they live in a different place or they have different customs.

To me, that looks like the same kind of colonial mindset that somebody was using their philanthropic dollars to push their own agenda of right and wrong, good or bad. These are not bad people. These people are doing what they think is the best. That was true even in the early days of America—people thought, “This is how we live; it works for us so it must work for everyone”. So it is people thinking they are doing well, usually, probably almost always; but sometimes they are hurting more than they are helping.

Q. Who are the worst offenders of such kind of behavior that you call ‘Philanthropic Colonialism’? Can you give some examples?

A. Well, I don’t really want to give examples because I don’t think people are doing that on purpose. If I call somebody out, if I call the name of the foundation or that person, it would be like I’m saying these people are bad people. They are good people. They are just behaving in a way that may not be the best for what they are trying to do. It’s not the people or the organizations that are bad. I did write that so it makes everybody to think a little bit, to think about how they are behaving and maybe they can think twice about it.

Q. You talk of ‘conscience laundering’ by the rich, which is to quote from your article “feeling better about accumulating more than any one person could possibly need to live on by sprinkling a little around as an act of charity”. What should the role of rich people be in philanthropy?

A. I know there are people that are making a lot of money doing things that are, for instance, not good for the environment or they pay low wages and it adds to poverty, or maybe there is a health risk. They are doing these things in the corporate world. They are making all this money and then they give it away oftentimes or at least sometimes, to the very things that are trying to solve problems they are creating, or the business sector they are in is creating. It may not be direct, but it is very much related.

So I call that ‘conscience laundering’ because I figure they must be feeling guilty somewhere—I hope that they feel a little guilty—so they would give money away to sort of feel better. I would much rather see people think about what they are doing in the first place, trying to make the world a better place by behaving differently than trying to patch it up after they’ve done the damage.

Q. In what ways is the work of NoVo Foundation different from what the other organizations do? How do you steer clear of ‘philanthropic colonialism’?

A. At Novo foundation, we are doing our best first of all to just be aware of that, to be super conscious about the fact that the world that we’d like to see isn’t really up to us to create. It’s not up to us to say, “This will make you feel better”, or any of those kinds of things. What we’re trying to do is to create conditions for change. So in other words, create conditions where people in poverty can have a voice to speak up and say, “This is what we need”, or people in the environmental sector, anything that seems to be an issue where philanthropy can go, instead of us saying this is the right thing to do, but saying, “You tell us what the right thing to do is”.

We are trying to listen better and create ways where we can hear you. So again, the problems get solved by the people that are experiencing it. That seems to make more sense to me.

Q. What do you do in order to hear people’s voices?

A. We are working with organizations that people would consider grassroots organizations. What we are trying to do is to get as close to the ground as we can. For instance, there’s one called the National Domestic Workers Alliance—these are domestic workers that have a network all over the country in different cities. So we find networks of people that have already been created that have strong leadership and a vision for the future. Because again, we don’t want to just put a bandage over something; we want to find out how people can have better lives for their children and their children’s children. So we really look for these organizations that are connected to the ground. You can give money to bigger philanthropic organizations but you never know quite where it goes and whether it’s effective and all that.

Q. How do you decide on what projects the NoVo Foundation will work on?

A. It’s always good to have people work with you that are smarter than you are. We spent a lot of time together talking about the kind of conditions we want to create, things we hope to see in the world. Then we start to look at the landscape of people working in certain fields, talk to them, learn from them, decide who will be really good partners, because we don’t want an organization—and this happens all the time in philanthropy—that is telling us what we want to hear. Because [many times the situation is like] we have the money, they have the project, and they will tell you whatever you need to hear to get the money.

We want a partner that will make mistakes, that will tell us the truth, and that will learn together. So a lot of it is really spending time getting to know the people in any particular organization where we think change could happen, and make sure we are working with strong leaders and real partners, so we can learn together along the journey.

Q. What is the core philosophy that guides your decisions regarding problems that are worth working on and those are not?

A. It’s certainly about doing the most good for the most people. Of course everyone will have to then need to define what’s good. We think, going to the most marginalized, the most distant franchised people—this would be, in the US, the service workers, domestic workers, people in the farming fields—it’s people who generally become invisible to a lot of the rest of our culture. We’re trying to go to the places where people either feel invisible or [are] made invisible. There are millions and millions of people that don’t feel like they have a voice. What we are trying to do is find projects that raise voices, amplify their voices, and find out how they can feel that they are a part of this world and this culture and have the same kinds of freedoms and access to all sorts of things that I would have.

I don’t want my life to be so different from the person I might be getting my food from, or [who] might be washing the car. Anybody that I come in contact with, I would like to think that they would have the same possible future that I would have. So for the foundation, we look for organizations and people again, that will lift those voices out so they can be heard and their lives can hopefully be changed for the better.

Q. What is your father’s philosophy of charity?

A. It’s interesting because many people call my father a philanthropist, but he actually isn’t a philanthropist. He has chosen to give his money away to other philanthropists for them to do the work. My father knows and has stated clearly that for him it’s a lot easier to make the money than to give it away. He knows how hard it is to not be ‘colonialist’ in nature….

Find good avenues for responsible philanthropy is a difficult job. His only directive—that’s the only thing he told us really, and there is a letter online that people can read—is to take chances, to make mistakes, to do things that other people wouldn’t.

His general philanthropic philosophy is to use the money in a way like risk capital. It’s probably the opposite of his investment advice for business. He’s saying, “take the risks, do the things that might not have return.”