Unprecedented economic opportunities and growing pressures mean China’s millennials stand apart from previous generations.

Exhibition centers aren’t obvious places you might go when looking to take the pulse of a nation’s youth, but in Shanghai in late September, this was the perfect place to be to understand the new cultural and economic power of China’s millennial generation.

Indeed, the Yo’hood street fashion trade show, held in the ShanghaiMart trade hall in the west of the city, drew thousands of millennials over the course of a single weekend. The annual event put on by the high-end street fashion, media and e-commerce company Yoho!—which received $30 million in funding last year—is now in its third year and goes some way in assuaging fears over China’s capacity to transition to consumption-driven growth, as well giving expression to one nascent, and well-moneyed, side of Chinese youth culture.

As attendees browsed through internationally renowned brands such as Hood By Air, Nike and Converse housed in eye-catching stalls, one of which was made to resemble a Brooklyn corner store, they could purchase items via Yoho!’s app as they walked along. In so doing these young people were showcasing China’s millennials’ penchant for exploring their myriad tastes and interests, often in ways previously unimaginable to their parents and grandparents. Just 20 years ago, Yo’hood would have been unthinkable.

Yet this is an increasingly complex demographic, who as well as enjoying the fruits of China’s reform and opening up are also beset by all manner of societal and economic pressures, making them arguably much more different from their parents than their Western counterparts are from theirs.

From an ever tougher job market to unobtainable home prices, millennials have to navigate a world with less security than was enjoyed by previous generations, all amidst slowing economic growth, to boot. And the many companies looking to sell to this increasingly important generation of consumers will have to grapple with all these issues, too.

Divided Generation

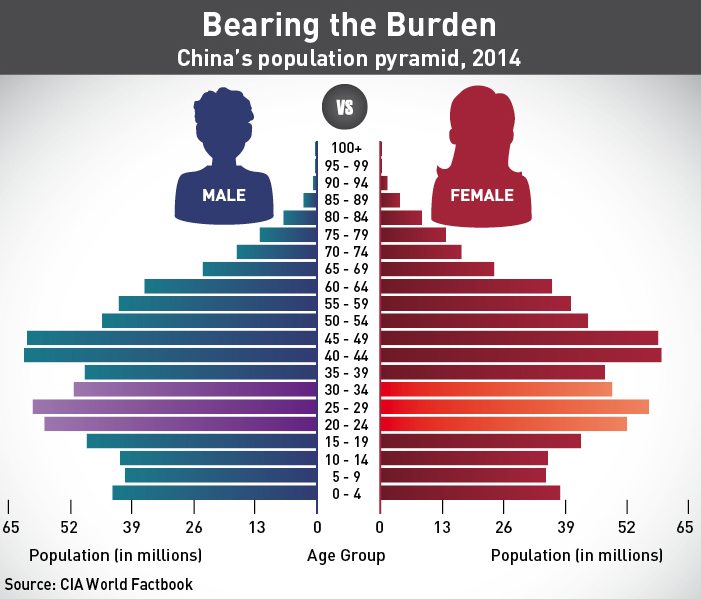

Millennials, the subject of so much discussion globally, are defined by the Pew Research Center as those born after 1980 and who came of age in the new millennium—in other words, those aged between 18 and 35. In China, this cohort represents 385 million people, or 28.4% of the population, according to the US Census International Database.

But while millennials are considered one wide demographic around the world, in China they are typically broken down into two distinct categories depending on the decade in which they were born—balinghou and jiulinghou, or post-80s and post-90s. Despite being born only a few years apart in some cases, the differences in the society they grew up in have been enough, generally speaking, to affect a different mentality between them, a gap largely attributable to increased internet access and a booming economy.

“Someone born in 1995 was born into an economy more than twice the size of someone born in 1985,” notes Eric Fish, author of China’s Millennials: The Want Generation. “And when that person born in 1995 turned 15, there was a 34% chance they already had internet access, as opposed to less than a 2% chance for the person born in 1985.”

This increased wealth and access to information has greatly enhanced the capacity for post-90s youth to explore their individuality in a way that post-80s couldn’t. “We consider them two ends of one spectrum,” says Kevin Lee, COO of China Youthology, a research and consulting firm in Beijing. “The post-80s generation were really the pioneers of individuality in China…. The post-90s are different, the post-90s are much more evolved in their individuality and the reason being is because they started [exploring their individuality] at a much earlier age.”

And this earlier exploration of their individuality has played into a noticeably different mentality between the two groups. “Post-90s tend to be more open-minded, rebellious, individualistic and willing to challenge authority than the post-80s,” says Fish.

Pressure and Prosperity

If there are differences within China’s millennial cohort, they are nothing compared to the chasm in experiences and attitudes between them and their parents—and grandparents.

“If you compare [post-90s] to previous generations—post-60s, post-70s—there’s no comparison. They are worlds and universes apart,” says Lee.

In part, this is due to China’s breakneck economic growth, which meant that millennials grew up without the scarcity that previous generations had come to know. They are also a generation that is much more familiar with the power and influence China now wields as a result of that growth, having experienced events such as the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the milestone of China becoming the world’s largest economy by some measures during their formative years.

In addition, they have enjoyed freedoms that previous generations were mostly denied. Previously one’s danwei, or work unit, would have been intimately involved in decisions regarding work, marriage, travel and children—as late as 2003 permission was required from danwei or other organs of the state for marriage, divorce and passport applications. Today, millennials are largely free to make these decisions without the interference of the state.

It’s a freedom they’ve embraced. Outbound tourism has increased massively in recent years, with millennials being a key driver. According to a Bank of America Merrill Lynch report released in March, by 2019 25-34 year olds are expected to make up 35% of China’s tourists, the largest segment. And millennials are increasingly heading overseas to study—459,800 people went to study abroad in 2014, an annual increase of 11.1%, according to the Ministry of Education.

That last statistic points to another important facet of China’s millennials—similar to their Western counterparts, they are much better educated than previous generations. In 2015 there were 7.49 million graduates according to the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, an increase of 220,000 from 2014.

Then there is the impact of China’s infamous so-called ‘one-child policy’ (in November it was announced it would become a ‘two-child policy’). Although perhaps overstated—the policy had been primarily implemented in urban areas and exemptions have existed for ethnic minorities and those in rural areas—a significant number of millennials have grown up without siblings. In the popular imagination, this has resulted in a generation that is selfish and demanding, the stereotypical ‘little emperors’ spoilt and coddled by both their parents and two sets of grandparents. But the reality is perhaps not completely aligned with this characterization.

“It’s definitely fair to say Chinese millennials are generally more demanding and have higher expectations (sometimes unreasonably high) than their parents when it comes to life, love and work, but is that so unique to China?” says Fish. “This concept also has a very urban middle-class bias and distracts from the huge number of young Chinese who are really struggling.”

And for some, they really are struggling. Those high graduation numbers have led to a glut of graduates and not enough appropriate jobs for them at a time when China’s rapid growth is beginning to taper off. According to a survey of millennials in China by J. Walter Thompson (JWT) in 2013, two years before stories of the country’s economic slowdown really began to dominate headlines, 68% of respondents said they felt people their age were struggling to find a job, and 76% said they thought their generation had been dealt an unfair economic blow because of global economic uncertainty.

“Many young workers—both white and blue collar—complained to me about how much nepotism and corruption there is in the job market, and how if you don’t come from a good family background or have connections, it’s really tough to climb the ladder,” says Fish. “There seems to be a widespread feeling that the prime period for wealth accumulation is in the past.”

Millennial Mindsets

These circumstances have given rise to a mindset that is at once both recognizable from millennials worldwide while also bearing its own Chinese characteristics centered on a new kind of individualism. “Our generation focuses more on concepts like individuality and freedom,” says Alan Meng, a post-80s post-graduate student studying in the UK.

Lu Xiaoming, a 30-year-old web magazine editor for a live music promotions company in Shanghai, agrees: “With my generation, as we are mostly the single child in the family, kids are used to a materially sufficient life, but the downside to that is you don’t really find a lot of peers to play with. That’s why my generation can be individualistic sometimes, and also, since you already grew up in a materially sufficient life, you tend to chase the adventure and thrill of life a bit more as well.”

This informs attitudes to work, even at a time when many find the job market difficult. Eighty-five percent of respondents to the JWT survey said their job should help them pursue their passion. There is also an entrepreneurial spirit amongst millennials—74% said they would just start their own business if they lost their job or struggled to find work. “Chinese millennials are more daring to try something and are more willing to change,” says Derek Zhong, a post-90s corporate social responsibility associate.

But that is not to say that China’s millennials have adopted Western notions of individualism wholesale, as traditions and notions of social responsibility such as filial piety still hold sway. According to JWT, 88% are proud of national traditions and customs, 91% think it important to hold on to family traditions and 75% believe that traditions hold society together.

“The collective is always the backdrop,” says Lee. “Their parents are all collective and the society that we still live in, the media, the schooling—everything is still quite collective.” But he points out that post-80s and post-90s approach this collective mindset in different ways. For the post-80s, it is about who they are in relation to other people and how they are seen—“a bridge mindset” compared to older generations, as Lee puts it. But post-90s are much less concerned with the perceptions of others beyond a select group, such as their friends.

But where China’s millennials are much closer to those in the West is in their enthusiastic adoption of technology and the internet: 58% of internet users are millennials, according to a July report from Bank of America Merrill Lynch. China’s millennials are also effectively mobile natives—a 2013 Telefonica and the Financial Times survey cited by China Daily showed 92% of Chinese 18-30 year olds owned a smartphone. “Information technology and social media in the last 15 years has really been a hallmark for this generation,” says Lee.

Making a Connection

For marketers, that naturally leads to a different approach when trying to reach millennials. “You’re not going to reach them by buying TV commercials or full-page ads in glossy magazines—you will meet them through product placement on TV and film, you will reach them on social media, if handled the right way,” says Michael Zakkour, Vice President, China/Asia Pacific of Tompkins International.

That is particularly true for Tencent’s ubiquitous WeChat app (see our story on page 15), although Zakkour cautions against using it with a traditional media mindset: “Don’t view it as a one-way conversation; it is a tool for social engagement, and you only need to look at the way Chinese millennials use WeChat in their everyday lives to better understand how to integrate your relationship with them and your brand.”

To an extent that is about appreciating the possibilities created by interactions between the online and offline worlds—an ‘omnichannel’ approach that Zakkour says is about making sure all of these channels are coordinated and integrated. In doing so marketers provide millennial consumers with choice—something that appeals to their individualistic personalities and life experience of growing up in a wealthier China.

The connectedness between these two things is something that Lee also stresses. “Most of the best brand interactions are actually offline, but what they do is they create many opportunities for the consumers, the participants and then bring that experience back online.” That is something Yoho! has done with their offline trade show, which then feeds back into their e-commerce and online media operations.

This interaction ties into what Lee calls “category culture” whereby brands create meaning and moments around their products or categories in order to drive engagement. “The questions is: how do we create our category and our category culture as something interesting enough… for consumers to talk about it and share about it,” he says. Ultimately, that is about making something relatable to millennials and authentic to them—for post-90s in particular, he says, “a brand is not just a faceless organization.”

Zakkour feels that an underappreciated approach is leveraging the rebelliousness of Chinese millennials. “What you can do through marketing, product and entertainment is tap into that rebellious spirit and let them wear and use those things in a subtle way that allows them to express their individuality and rebelliousness without breaking societal norms,” says Zakkour. He points to Vans as an example of a brand that has done this—and they have also successfully used its all-day ‘House of Vans’ art and music events offline to drive interest in the brand and augment its existing subcultural associations.

But not every company has been as successful as Vans, and the list of those identified by experts and millennials as having been so is relatively short. Apple, naturally, is cited by many, while the tech company such as Xiaomi is known for its youthful following. Nike and Adidas are also pinpointed as having significant traction with millennials. Beyond these, examples are less clear cut.

Bright Future?

China’s millennials represent the future for both their country and many of the companies operating there, but it’s a future with a few clouds on the horizon.

Change has been so rapid in the last few decades that certainty has been in short supply, but if the days of double-digit growth had come to be taken for granted, they aren’t anymore. This so-called ‘New Normal’ (see our story on page 10) represents a new kind of economic and social uncertainty for China’s millennials, particularly the post-90s generation, who will now have to contend with the effects of the slowdown.

“I won’t say me or a lot of my peers are actually aware of the slowing economic growth, but the skyrocketing apartment prices and rent money definitely have a impact on all of us, which results in late marriage and a high divorce rate, and people can’t really spend as much as they want on lifestyle choices,” says Lu, the web magazine editor, although he notes that “most of them spend it anyway.”

And then there is China’s ageing population, another result of the low birthrate caused by the one-child policy. As well as leading to increased responsibility for millennials, this shift will also make older generations an important demographic for businesses to focus on.

Still, like their peers worldwide, China’s millennials manage to find optimism and self-confidence even while harboring a degree of negativity about their situation. That speaks to the many nuances of this generation, a fact only enhanced by its post-80s and 90s subdivisions.

But as millennials become more and more influential and their purchasing power increases—as it surely will—brands will need to grapple with this complexity. They may find that reaching China’s consumers is quickly becoming that much more complicated, not least because this is relatively uncharted territory for so many on both sides of the sales counter.

“I don’t think the vast majority of brands inside and outside of China have really gotten on board with the opportunity yet,” says Zakkour. “There’s a limited number of success stories we can point to because not everybody has moved aggressively in addressing that demographic—and they need to.”

(Additional reporting by Francesca Chiu)