Like its whole economy, China’s auto market grew at breakneck pace in the 2000s, and while it is now slowing down, it still contains enormous potential in terms of both raw sales and innovation as China shifts toward electric

Eric Zhang recently turned electric. That is, the 29-year-old marketing professional from Beijing recently bought a BYD E5, an all-electric sedan made by Shenzhen’s BYD Auto. He is one of three people in his immediate circle of friends to buy a new-energy vehicle (NEV) this year.

Zhang says they all made the choice based on a practical consideration of license registration and cost. Beijing is one of eight Chinese cities that have restricted the number of conventional vehicles on the roads. In 2011, the city introduced an annual public lottery to decide who would be eligible to register new internal combustion engine cars.

“The chances of winning are lower that 0.2% in Beijing, which means many of us, even if we enter the lottery repeatedly, will die before we get a license,” says Zhang. NEV licenses are not won through a lottery, but simply bought after standing in a queue.

Influenced by the push-and-pull of government policies, car buyers like Zhang are transforming China’s auto market. China’s NEV sales volume surged from 8,000 units in 2011 to 507,000 in 2016, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM). It is a sharp contrast to the slowing growth of overall automobile sales in China.

“NEVs are increasingly an option due to government incentives,” says Stanley Yan, Senior Analyst with Franklin Templeton SinoAm Securities. China provides subsides that amount to about 23% of the price of a vehicle. That’s lower than some Scandinavian counties, for example Denmark’s 29% subsidy, but higher the US’s 18%.

Although the NEV market is on a steep upward trajectory, it is also beset by problems in terms of both developing technology, and in the creation of a marketplace that can succeed in the in absence of state support.

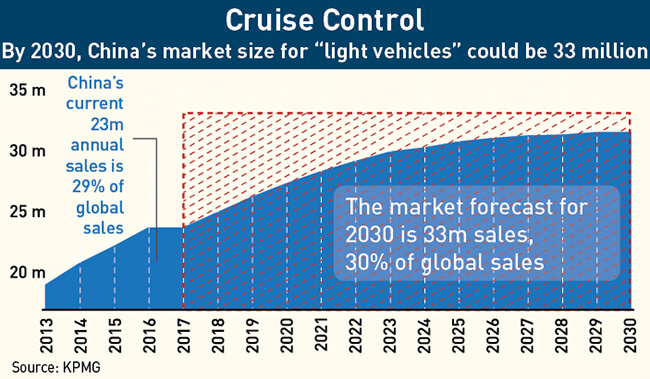

Cruise Control

“China’s automobile market is maturing,” says Bill Russo, the Shanghai-based Managing Director of Gao Feng Advisory Company, a strategy and management consulting company. He says slower growth is becoming the norm and sales increasingly skew towards new-energy vehicles and cars with high-tech functionality, such as self-driving capabilities.

In the first half of this year, sales of passenger cars totaled 11.25 million, up by only 1.61% from the same period last year. This is a significant downshift for an industry that has been a world-beating growth machine for decades. China’s modern automobile industry started in the 1980s, when foreign manufacturers like Volkswagen entered China to set up joint-ventures. Later, local producers like Geely Auto and Great Wall Motors were founded. In 1985, the infant industry produced 5,200 vehicles. Growth remained low until 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization, and then the market boomed.

The growth rate of passenger car sales surpassed 56% in 2002, and maintained double-digit growth for years afterwards. In 2009, China overtook the US to become the world’s largest car market, with sales surging 46% year-on-year to hit 13.6 million vehicles.

“Several of my colleagues and I purchased our first vehicles in 2001 and 2002, and we received generous car allowances from our employer,” recalls Mingxin Zhao, who works for a government-owned company in Beijing.

Mirroring an overall slowdown in the economy, the car market has since grown sluggish. In 2015, annual growth of car sales was just 4.7%, according to CAAM. The government reacted by introducing nationwide tax incentives in 2016, which resulted in a 13.7% year-on-year surge with 28 million cars sold. But according to Russo, the tax incentive merely caused consumers to move up planned purchases—and indeed, this year the impact has faded with auto sales posting year-on-year decreases in both April and May.

Consumer attitudes towards cars are also changing. In a 2016 survey of 3,500 Chinese consumers by McKinsey, about half of respondents indicated that car ownership is no longer a status symbol. However, the number of consumers who say they are interested in buying an NEV has tripled since 2011.

For consumers in first-tier cities, purchasing a new car is only one of several options open to them. “Alternatives like buying a used car, leasing or renting, and relying on e-hailing and car-sharing services hold increasing appeal,” said the McKinsey report. Rental and sharing services could reduce annual vehicle sales by 10% by 2030, McKinsey predicts.

Russo echoed McKinsey’s findings. In addition to the disruptive forces identified by McKinsey, he says, “Hardware innovations, such as autonomous driving technology, will be commercialized through the development of on-demand mobility services and the larger digital ecosystems.”

Bumpy Ride

Central to the changes outlined by Russo and McKinsey is the push for new-energy vehicles. But despite the excitement and solid growth numbers so far, there are challenges ahead.

Even as an owner of a new NEV, Eric Zhang still has doubts about their overall competitiveness against petrol-driven vehicles—not the cars themselves, but the charging stations. “The lack of power stations means we rent a gas-powered car for long weekend trips,” Zhang says.

The government is working to address this as part of the electric vehicle push. In the “Made in China 2025” initiative unveiled in 2015, the NEV sector was listed as a prioritized industry and plans were included to subsidize charging stations. At the end of 2016, the State Council also announced that it would tighten planning regulations for new factories that plan to build traditional vehicles with internal combustion engines. The thinking being that stimulating electric vehicle production should stimulate charging station construction.

“The NEV industry has strategic importance for China, not only for the automobile industry to compete globally, but also for pollution control and energy independence,” says Stanley Yan.

Since 2012, the Chinese government has spent billions subsidizing local electric car and battery makers. Most notably, its support has been critical in helping the Shenzhen-based automaker BYD, in which Warren Buffett has a stake, to become the world’s largest electric car and bus maker.

But the carrot-and-stick strategy has some issues. “The approach has stimulated the NEV market, but also created negative developments in a few cases, such as fraudulent behavior among some manufacturers for subsidies,” says Hoi Tran, Partner and China Head of Automotive, KPMG China.

The low-end NEV power battery sector is expected to enter overcapacity status in 2018, with fragmented manufacturing and insufficient innovation, said Zhang Junyi, a partner with Nio Capital, an investment firm co-established by electric vehicle company NextEV, Sequoia Capital and Hillhouse Capital. “Meanwhile, the production of high-end power batteries for premium electric cars still lags demand, and the core NEV technology trails behind global competitors,” Zhang says.

To tackle the problems, four government ministries announced in January this year that subsidies for NEVs will decline by 20% from 2016 levels. The Chinese government is also seeking to acquire advanced foreign technology through regulatory changes.

In January 2017, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) issued a market-entry requirement for NEVs, which forces manufacturers (including joint ventures) to disclose details of the technology used in development. MIIT is also expected to introduce a quota system in 2019, which will require all large automobile manufacturers to produce NEVs (10% of their output in 2019 and 12% in 2020). Those who fail to meet the targets will face financial penalties, including potentially losing their license to sell traditional cars in China.

The quotas talk triggered instant partnerships between foreign giants and local NEV producers. Examples include Volkswagen’s JV with Anhui Jianghuai Automobile Group, which was announced this May, while Ford Motor’s JV and Anhui Zotye Auto sealed a tie-up this August for NEV production. Both Jianghuai and Zotye are among the top ten NEV manufacturers in China.

The medium-term goal of the government is to have five million NEVs on China’s roads by 2020, but some see this as unrealistic. “Once China reduces subsidies to NEV manufacturers and consumers, NEV growth will be challenged,” concludes Stanley Yan.

Promise Remains

China, as the world’s most populous country, still offers opportunities to both domestic and international auto manufacturers. “China will be the dominant marketplace in terms of market size, innovation and consumer behaviors in the future,” says Hoi Tran. He expects lower-tier cities will experience double-digit growth in coming years.

In KPMG’s Global Automotive Executive Survey 2017, global executives also see China’s future as bright. China aims to have 70% of its population—some one billion people—living in cities by 2030, up from less than 60% at present. This increasing urbanization is expected to provide abundant market opportunities.

The KPMG report also highlighted the openness of Chinese consumers to try new things. Executives rated China over Germany and America in terms of consumers’ adoption of new and disruptive products and mobility services.

“Chinese consumers are a major force for innovation as they are open to new technologies,” says Hoi Tran. “Given the high penetration rate of mobile devices and the adaptation to e-commerce, mobile banking and social media, technologies have become an integral part of the everyday life of a Chinese consumer.”

This phenomenon will drive innovation in China’s automotive industry, including NEVs, in the form of connected cars that integrate with wireless networks, and self-driving cars. Last year, the Shanghai state-owned car-maker SAIC launched its first “Internet car,” the Roewe RX5, with e-commerce operator Alibaba. This connected vehicle integrates into the “Internet of Things,” connecting to both the web and other devices. The model sold more than 90,000 units in 2016 after hitting the market in July, becoming the most popular new nameplate among 93 models launched in China last year.

The popularity of the RX5 may have been helped by the fact that it is an SUV, a vehicle type gaining popularity across the board. China’s SUV sales totaled 4.53 million in the first half of 2017, up 16.83% year-on-year, making it the only growth segment among passenger cars.

Overall, the future remains bright. According to the KPMG survey, 75% of executives believed that the global share of vehicles sold in China will be above 40% by 2030, or 43 million cars annually. But China’s vehicle-to-population ratio (currently 106 vehicles per 1,000 people) is unlikely ever to reach the US level of 800 per 1,000.

In a nation infamous for miles-long traffic jams, that may not be a bad thing after all. But, cautions Russo, “China is still likely to approach Taiwan’s current level of 280 vehicles per 1,000 in the next 10 years.”

New Frontiers

The desire of Chinese domestic automakers is to go global, but exports accounted for less than 5% of automobile output in the past five years. “Chinese manufacturers still need to improve international competitiveness, especially in developed markets, but there will be a growing trend for Chinese car makers to venture internationally,” predicts Zhang Junyi. This includes building factories abroad and expanding sales into more markets.

Several automobile brands including Geely, BYD, Jianghuai Automobile, BAIC and SAIC, have built factories overseas, according to the CAAM. In August this year, Xu Haidong, secretary-general of CAAM, said the international expansion has been viewed as a necessary path for Chinese automobile makers to grow from being big to being strong.

The lower cost of Chinese automobiles gives China an edge in African, Southwest Asian and Latin American markets. But the development plan issued by MIIT and several other ministries this April has set a challenging goal of selling Chinese cars into developed markets by 2020—though Toyota eventually became a hit in the US, it failed hard when it first entered the market in the 1950s.

In recent years, Chinese car companies have tried opening research operations in advanced markets to attract top technicians and technology. One example is Great Wall Motors, which has built two technology centers in America for research into innovation in automobile components. The company’s exports surged by 154% to 17,100 units in the first half of this year, but exports still accounted for only 2.64% of total revenues.

Independent innovation in the Chinese automobile field, a stated target of the “Made in China 2025” initiative, remains weak and manufacturers are dependent on key foreign technology and equipment. But Zhang Junyi believes that gaining a head-start in the development of NEVs would create new opportunities for China in international markets, particularly with the Trump administration apparently backing away from supporting such technologies.

More mergers and acquisitions and overseas expansion are expected in the NEV sector, according to analysts. Just this year, Chinese battery giant CATL acquired a 22% share in Finnish car manufacturer Valmet Automotive, while BYD set up a production facility in California, employing 700 people.

Despite the limited presence of Chinese automobiles internationally, future opportunities loom large. Currently, China is already the world’s largest passenger car manufacturer, as well as the top NEV exporter. With China’s production chain beginning to expand globally, “the world is likely to be driving far more cars from China in the near future,” summarizes Stanley Yan.