China is the world’s top consumer of pork. What has the impact of African swine flu been on the meat industry and food security in the country?

China’s meat industry has been hit in the past couple of years by two devastating viruses: Bird flu and African swine fever. The renewed bird flu outbreak led to mass culling of chickens, but even more serious is the fact that close to half of China’s 442 million swine stocks were killed last year either by African Swine Fever or by the preemptive killing of pigs to stop its spread.

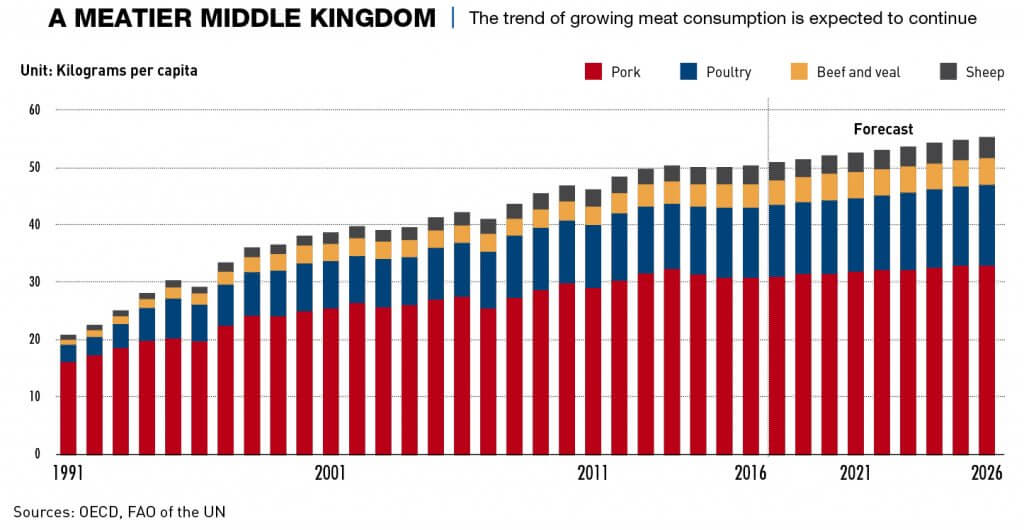

African Swine Fever first struck China in August 2018 and has decimated the world’s largest pig population, creating economic disaster for farmers, as well as sharply pushing up meat prices and overall inflation. China has a large and still growing appetite for meat, but the first signs are emerging that these diseases are leading to a shift away from traditional pork consumption habits, which have big implications for farming, the environment and international trade.

“Since the beginning of 2019, deaths and panic slaughters have caused steep declines in the pig population,” says Dan Wang, China analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), “with many smaller farms having exited the market.”

China is far and away the world’s top consumer and producer of pork, and the country’s pig farms are home to about half the pigs on the planet. Every year, the country devours 55 million tons of the meat, which is a key staple of the national diet. But pork output last year plunged to a 16-year low, creating food shortages in some areas and causing pork prices to shoot up more than 100% by the end of the year. The agency that manages the government stockpile of frozen pork has been releasing large quantities since September 2019 in an effort to ensure market stability.

African swine fever has had “a huge impact on the supply of pork,” says Miranda Zhou, senior analyst at Euromonitor International, a research provider. Rising prices and damage to consumer trust in the safety of eating pork has encouraged some people to shift to other protein sources such as poultry and eggs. And with overall rising incomes, some middle-class Chinese are also opting for pricier, higher-quality meats such as beef.

New trends in meat

China produced 86 million tons of meat in 2018. The country’s meat industry was valued at $157.5 billion in 2019, with pork at $110 billion, close to 70% of the total, according to Euromonitor. There are approximately 26 million pig farmers in China, of which 30% are small-scale “backyard” operations.

Chinese people ate just short of 30kg of meat per capita in 2018, of which 22.8kg was pork, 2kg beef and 1.8kg mutton. Poultry and seafood, categorized separately, averaged 9kg and 11.4kg per person respectively.

“Historically, China is very much a pork consumption country,” says Adam Xu, partner at OC&C Strategy Consultants. “And the price of pork is much lower than beef and mutton.”

Pork is sure to remain number one in overall share, says Hongzhou Zhang, a research fellow at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore and author of Securing the “Rice Bowl”: China and Global Food Security. “But given the recent prices of pork, people have had to cut back on their consumption because the price has become insanely high for poor or ordinary people.”

However people may be slow to change their consumption habits. “I would call myself a meat-oholic,” says Zixuan Wang, a 26-year old Beijing resident who spoke to CKGSB Knowledge. And despite the rising price of her favorite meat, Wang says she isn’t planning to change, as beef and lamb remain expensive, too. “A higher price is not a big issue yet. I usually spend a lot on food.”

Animal farm

In terms of total domestic consumption, meat imports are small, accounting for just 3% of domestic consumption volumes, according to EIU’s Wang. “Imported pork makes up a bit more than 2% of total pork consumption, and imported beef—fresh and frozen—about 14% of beef consumption,” she says.

The main beef exporters to China by volume are Argentina, Australia, New Zealand and Uruguay, while Canada, Germany, Spain and the United States provide most of the foreign pork. Pig liver and other types of offal, often discarded by western European and North American consumers but enjoyed in China, make up a significant portion of the imports.

Food security is always one of the top issues, says Chenjun Pan, a senior analyst of animal protein at Rabobank. “China can be self-sufficient in poultry—imports only account for 3% of total supply—but the reliance on [imported] beef is rising,” she says. “This year, imports may increase the share further.”

In a win for pork security, WH Group, China’s largest meat processing company, expanded its market dominance when it purchased the US-based Smithfield Foods in 2013—the largest pork processor and hog producer in the world.

Disruptors

For a number of reasons, China is especially prone to the spread of animal diseases, known as zoonotic epidemics. Peter Li, associate professor of East Asian politics at the University of Houston-Downtown, specializing in Chinese politics, environmental governance and animal welfare, cites industrialized farming operations, drug resistance, overcrowded caging conditions and enforcement shortfalls among the factors.

The current meat disease situation, he says, is in some ways a rerun of 2006 for China, when it was Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome, more popularly known as Blue Ear Disease, that devastated pig farms. “That’s why public health is a tremendous issue,” Li says.

Health and environmental beliefs are challenging the food and agriculture industries globally—with unease over the impact of red meat on heart disease and carbon emissions. Still, in China, food safety remains the number one concern, says Li. “Global warming is a hot issue in Europe and the United States, [but] it’s not a major concern among the Chinese public, [not] even among the highly educated 5% of people.”

In 2016, the government revised its Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents to encourage the nation to opt for more fish or poultry over fatty, smoked and cured meats. But the concept of healthy is open to interpretation, too. “People think meat is good for kids and young people, but not so good for elders,” says Zixuan Wang. “My parents, 55 years old, and their friends eat less meat to keep healthy now, but it’s not for the environment.”

“I think consumers in general believe that meat is not bad for them,” says Xu. “Everything is about consuming an appropriate volume. We have not yet reached the stage where we over-consume protein while reflecting on the impact on the environment and on our health.”

The pork cycle

Following the African Swine Flu outbreak, many smaller farms, lacking government subsidies and dealing with skewed insurance schemes, have been forced to shut down.

“This is causing tightness in supply,” says Dan Wang. “Large pork-producing provinces such as Heilongjiang, Henan, Jilin and Liaoning have seen a decline of more than 50% in production capacity.”

Small-scale farmers, under pressure to pay back loans, tend to bend the law for profit, with excessive veterinary drug use and widespread violations in every step of farming operations, according to Li. Local officials turn a blind eye, scared that shutting businesses could trigger local unemployment and social unrest.

Retailers are selling a larger share of frozen meat stocks and pork prices have more than doubled from a year ago, having spillover effects.

“The pork cycle is the most important component in inflation,” says Dan Wang. As the single largest item in China’s Consumer Price Index (a measure of the weighted average of prices of a basket of consumer goods and services), pork accounts for 2.4%. “A 10% increase in the price of pork will add 0.24 percentage points to the rate of headline consumer price inflation. Pork has experienced two price cycles since 2009, each lasting around four years. We are currently on the rising wave of the third cycle,” she says.

Pork prices rose a staggering 135.2% in February compared to the year before, and up 9.3% since January. Overall livestock meat prices grew by 87.6% year-on-year, adding nearly 3.85 percentage points to the CPI in February. Pork boosted inflation by as much as 3.19 percentage points that month. Wang estimates that even without swine fever, the pork price was on a rising cycle and would have increased 50% last year. But instead prices are up three times as much, without yet peaking.

This is boosting consumption of substitute protein, such as beef, poultry and seafood. As a result, beef prices registered a 20% increase in February compared with a year earlier. Mutton was 11% more expensive.

Feed prices are affected too. China has committed to import massive amounts of soybean from the US while the domestic pork industry is shrinking. “Feed prices are likely to drop as a result, which will benefit pig producers,” according to Wang.

Social stability

Food security has political stability and legitimacy implications. But the government understands that “inflation is the number one cause for social instability, and even political crises,” says Zhang, which is why pork was added to the national meat reserves after Blue Ear Disease ravaged the market in 2006.

China’s frozen pork reserves are designed to calm markets in times of temporary shortages and runaway food prices. But Wang says the pork reserves play a limited role in stabilizing meat prices. “It is more a symbolic move to calm market sentiment since pork price is a sensitive social issue. In sensitive times, like before Chinese New Year and during the coronavirus outbreak, pork reserves are auctioned out to stabilize prices for certain regions.”

Wang estimates that the reserves make up less than 1% of annual output and can only be used to stabilize prices in a few large cities for from three to six months. The exact size of the reserves is a state secret. Zhang suspects that a lot of imports go directly to the reserves instead of to markets.

New protein

Thanks to diseases and other factors, protein sources are changing, and some of the urban middle class are shifting away from pork. Zhou reckons pork will remain the mainstream protein source, but meats with lower fat and cholesterol, such as poultry, fish and shrimp, and higher nutrition, like beef and lamb, will become more popular as people shift to healthier options.

Similar motivations explain the rise of vegetarian and alternative protein diets globally. Faux meat producers Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat are both planning a China launch, and homegrown startups are catching on, too—with Whole Perfect Food and Starfield in Shenzhen, Zhen Rou in Beijing and Green Monday in Hong Kong.

Vegetarianism is not a new concept for China and meat substitutes date back at least to the Song dynasty, when “mock meat” made from wheat gluten, soybeans and mushrooms formed the core of Buddhist-friendly cuisine. Still, “veganism and fake meat are niche,” says Zhou. “Although there have been some attempts on fake meat products, they don’t receive very positive feedback.”

Overall, meat consumption is not decreasing and rural consumers, who eat as little as 1kg of beef per year on average, still provide big room for growth of meat sales. Rural migrants, especially, will change to meatier diets as they continue to move to the cities, says Zhang.

Zhang predicts consumption to become more diversified in the years ahead. “The overall share of pork of animal protein will decrease, and then you will have more consumption of chicken, fish, and, of course, beef,” he says. “I think China will import more of all sorts of meat products from the global market. Self-sufficiency is simply not possible. Total meat consumption will still go up. And then a rising amount of the food consumption, or the gap, will be met through imports rather than domestic production.”

But is all of this enough to wean people off meat?

“For Chinese people meat is very important,” says Shen Wei, a 36-year old who lives in Ningbo. Even if people eventually eat less of it, he says. “It would be impossible to eat no meat at all.”