A huge shift in trade and relations could be underway across Eurasia, and China’s New Silk Road policy is at the heart of it

As a historical reference point, the Silk Road continues to resonate, long after the trade route served any economic purpose. For Europe, it evokes the slow sway of camel trains across parched landscapes and the flow of exotic goods into the continent. And in China it brings to mind the touchstones of its imperial history and its connections to the outside world.

When China’s president Xi Jinping laid out his plans to establish a “New Silk Road” across Central Asia in 2013, he was doing more than invoking China’s distant past. Instead, he was sketching out a new direction for Chinese trade and investment, one that aims not only to improve China’s links with Europe, but also to facilitate trade across the entire Eurasian land mass, an ambition welcomed by many regional leaders. President Nursultan Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan—when attending the opening of a new rail link between Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Iran in December 2014—said, “We have virtually created a new Silk Road running across our three countries and China to the Pacific Ocean.”

However, for China the potential scope of the policy is larger than is often perceived, and the alignment of interests extends well beyond improved trade links. Indeed, if the policy gains traction, it will facilitate China’s macroeconomic priorities, further open up China’s vast interior and may help to reconfigure the nature of China’s integration in the global economy. In that sense, the New Silk Road is less a trade route for the modern day silk of raw materials and manufactured goods, than a road map to China’s future as a developed, open and free trading economy.

Wider, Ever Wider

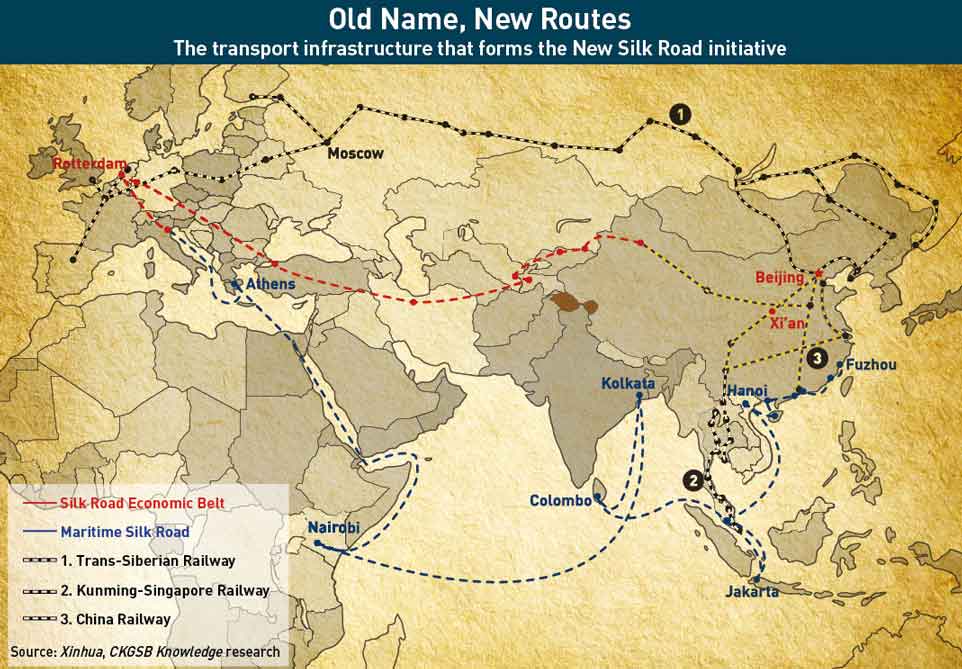

When Xi Jinping announced the New Silk Road plan in Kazakhstan in September 2013 he made explicit reference to a “strategic regional thoroughfare from the Pacific Ocean to the Baltic Sea”. At the time, commentators linked this to the long planned New Eurasian Land Bridge, conceived originally as a network of rail links west, from the coastal city of Lianyungang, through China to Kazakhstan, there linking up through Iran and eventually crossing under the Sea of Marmara in Turkey, creating an uninterrupted rail link to Europe. This route would be in addition to the Trans-Siberian route, which already hosts two regular freight connections between China and Germany and a recently trialed rail service reaching as far as Madrid in December 2014.

Xi went on to call for a “move toward the set-up of a network of transportation that connects Eastern, Western and Southern Asia”, widening the scope considerably, and potentially involving all road and rail investments in the region, including within China.

The following month, in a speech given in Jakarta, he made reference to a “Maritime Silk Road” focused primarily on Southeast Asia and both concepts have since progressed in tandem under the broad heading of the “New Silk Road”.

Here, the value of a long-term strategic vision becomes clear, with the overall plan allowing China to progress in small steps, cultivating strong links with then President Mahinda Rajapaksa during Sri Lanka’s diplomatic isolation following the end of the civil war, and being ready to invest in the port of Piraeus, Greece, just as economic collapse forced a fire-sale of national assets.

According to Song Gao, Managing Partner at PRC Macro Advisors in Beijing, “Chinese officials say there are three routes, one goes north through Mongolia and Russia to Germany, another goes to Central Asia through Xinjiang province, and the third one is the Maritime route.” Which, if it remained simply that, would still sketch out a vast area. Importantly, it has the full backing of the leadership, so far gaining the status of a signature policy for Xi Jinping’s presidency.

Both Xi and Premier Li Keqiang have made extensive visits to countries along the various routes, talking up the policy as the basis for constructive future relations based on trade and investment, with Xinhua, China’s state news agency, providing routine fanfare.

The project is also backed with serious money. The new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and a new Silk Road Fund have seen Chinese capital totaling $90 billion established as seed capital, with a further $60 billion available from other funds. Clearly when China speaks of the New Silk Road, they mean business.

Trading Up

From the outset though, the New Silk Road initiative has been less about specific routes, than it has been a policy framework. And perhaps even before this it was a question of political symbolism. According to Song, “The announcement of the New Silk Road from a political perspective is a commitment for the new leadership to assure everyone that China still sees free trade as a way for China to achieve sustainable growth.”

Moreover, it is a statement of intent to other countries. He Liping, a professor at the School of Economics and Business Administration at Beijing Normal University, suggests that “it is a reflection that China and China’s leaders want to make friends with many countries around the world, particularly those that are geographically close to China,” adding that, “in this sense it is a diplomatic effort”.

However, even when reduced to transportation infrastructure investment, the policy creates alignments with other regional efforts, and indeed domestic initiatives.

For the Chinese interior, the promise of increasing westward transport volumes raises the prospect of faster development with less dependence on routes to the coast, helping to spread the so-far uneven benefits of Chinese growth.

On a regional level, deeper investments in transport connectivity across Southeast Asia, progress towards free trade with South Korea and emerging economic rapprochement with Japan all point to a possible future in which China is no longer simply a destination at one end of a trade route, but an enormous transportation hub in which trade flows in all directions, providing—for example—improved access to Central Asia for Japanese and South Korean exports.

The New Silk Road policy framework ultimately serves to unite this long-term vision with China’s diplomatic and trade policy orientation, in order to coordinate many different government departments, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and policy banks around the goal of loosening restrictions—both domestic and international—on trade.

Daniel Tobin, Lecturer in Chinese Business and Management at the China Institute, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, explains: “Economically at least, it’s a very rational policy. Putting this thing on paper, using it as a selling point, getting people to talk about it and making trade easier is a very rational policy.”

Chinese Horizons

But to focus purely on trade is to miss many other aspects of the New Silk Road policy. Of perhaps greater importance in the short-run are macroeconomic factors, something that has become more acute as economic growth has slowed and the need for some kind of stimulus has arguably risen.

“We’re getting a good idea at this stage that the sort of consumption-driven growth that the leaders had in mind is not really materializing,” says Tobin, adding, “if these are Chinese [investment] projects, carried out by Chinese companies… the leakage out of them is quite small I guess, so the money spent does come back into state coffers and it keeps growth going forward.”

Beyond forming a kind of stimulus, the long-term project of internationalizing the renminbi is often mentioned in connection with the New Silk Road. “Something that makes trade easier is currency and removing currency restrictions and giving a lot of these countries quotas in renminbi… [is] quite a coherent policy,” says Tobin.

Song Gao extends this analysis by highlighting that a “medium-term goal for Beijing to internationalize the renminbi is to make [it] a more important currency for trade settlement, especially regional trade settlement.” And given that “a quarter of China’s exports have been associated with countries along these two or three routes,” the impact on the volume of renminbi trade settlement will not be trivial.

Thirdly, but perhaps most significantly, according to Li Haitao, Dean’s Distinguished Chair Professor of Finance at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, attempts to alleviate growing economic pressures on Chinese businesses plays a role in the scheme. “There is a huge amount of overcapacity in manufacturing and real estate and related industries… the New Silk Road, people refer to it as China’s Marshall Plan to try to export this overcapacity to Central Asia, South Central Asia, Indonesia and Southeast Asia, all the way to Africa. That’s a great idea if it can be successfully implemented.”

Song further explains that “the New Silk Road is a scheme to convert China from a capital inflow country to capital outflow country”. Consequently “China will put foreign reserves to much better use because it has been getting about 0% or 0.5% return on [US] federal bonds. Now, if they put the money into infrastructure in developing economies, it should give a better return for China’s foreign reserves.” Furthermore, this will allow China to “export some inflationary pressure and can—in that case—give the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) more discretion in implementing domestic monetary policy.”

Return on Investment

Inevitably, such a bold, long-term plan will face challenges, and those challenges will be commercial, economic and political. But although a focus on trade might seem like a “win-win” for all those involved, from the perspective of business, the benefits are not as clear cut. A senior source from the Asian freight industry thinks the direct benefits of better rail links between China and Europe would “probably not be much, based on cost. You’re looking at a difference of 14 days into Europe as opposed to four to six weeks by sea, but of course at the moment the costs are much higher, so it really depends what sort of commodity you’re moving, what value it has and how time sensitive it is, but it’s certainly going to have an impact going forward.”

This restrained skepticism is reflected in wider market-based views of the New Silk Road. “Although obviously we are interested in specific investments across the region, the ‘New Silk Road’ is the sort of strategic policy initiative that generates little in the way of obvious and direct tangible benefits,” says Jonathan Silver, Banking and Finance Partner at the law firm Norton Rose Fulbright in Hong Kong. “So while business would generally welcome the potential benefits of the New Silk Road, most would only take a direct interest in the concrete results, as they arise.”

However, the establishment of state-backed funds and policy banks to drive investment highlights at least one acknowledged problem with large-scale infrastructure investment—the difficulty of securing a return—and hence the need for such financial institutions, rather than commercial and investment banks, to provide funds. “When you come to think about what type of returns these projects are going to deliver, you could be very skeptical of something like putting a lot of money into a railway line upgrade. These things don’t generate big returns in economic terms,” says Tobin.

Such doubts would seem to run counter to the grand historical analogies. But rather than contesting the underlying logic or direction of the policy, a lack of excitement stems from the fact the New Silk Road essentially follows a well established direction of Chinese policy of simply making trade easier.

“It certainly is making it easier to trade with these countries, makes for a nice announcement and it has a nice name. It involves a lot of capital expenditure, but it’s not necessarily something new,” says Tobin, who adds, “when you’ve been looking at these things for a while, you tend to get quite skeptical about the way things are packaged, the way things are announced and the names given to them… The control that the Chinese government has been able to exercise over investment is not very good. It’s not a perfect lever for them… The policy is consistent in one sense, but the big problem always seems to happen with implementation.”

Moving beyond trade and implementation, it is also clear that some of the hoped for macro-economic benefits will be difficult to realize. CKGSB’s Li expresses particular skepticism that the New Silk Road will make much difference at all to the problem of overcapacity in China.

“When I first heard about this, I thought it was a brilliant idea to try to solve the overcapacity problem in China… but if you look at these countries on the Silk Road, just think about a country that is big enough, that has huge demand for infrastructure building, could be India right? It’s the size of China, huge room for improvement, but do you think India would open its doors and let China in to build all the bridges and roads?” he says. “You have to transform India into China in order to take this overcapacity [but] they want to do it themselves.”

“The bottom line—to me—is that there is no free lunch. This [the New Silk Road] may help, but it is not a panacea. There may still be some pain we have to endure to deal with overcapacity in China.” Furthermore, Li reinforces the difficulty of making these investments pay, noting that “the government is reducing their holdings of US government bonds, and if you can export this capital and invest in real assets… that is definitely a good strategy. But having said that, if you look at the economies around the world, the US is the only bright spot.”

Political Preoccupations

Setting aside the mundane matter of threading the whole idea together with actual steel, concrete and trade agreements, there is also the question of politics, or at least, the question of political perception.

“The political challenge being always associated with the general perception of Chinese diplomacy and foreign policy,” says He Liping.

For Song the problem is potentially more serious. Focusing on the three basic routes that comprise the spine of the New Silk Road, he says, “If these three routes become so important to China’s future sustainable economic growth and also become so critical to China’s export of capital, that means these routes will bear significant national interests and will matter a lot to China’s national security… This, naturally, will be at odds with some major global powers. Russia will definitely have concerns with China’s expansion through Central Asia, and India, for the maritime route, China will have to secure the trading route through the Indian Ocean, that will at least be perceived as a threatening move.”

Indeed, so threatening that India is developing its own strategic vision for the Indian Ocean region—so far called ‘Project Mausam’—as a direct response to China’s New Silk Road.

Nevertheless, there are signs the Chinese government is fully aware of these potentially negative perceptions. On December 15th, 2014 Li Keqiang suggested in a speech in Kazakhstan that the New Silk Road would need to resolve security questions through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). In doing so, he openly acknowledged a security dimension to the New Silk Road, but framed it in terms of instability and terrorism rather than geopolitical competition. Furthermore, invoking the SCO as the vehicle for security cover acknowledges Russia’s interests in the region while hinting that they may not always be exclusive; a cooperative position, and one that Russia will no doubt think carefully about, but a suggestion clearly intended to reassure.

One further advantage China has is simply that the scale of the New Silk Road means that opposition from anywhere will only ever be towards part of the whole. The US will not be concerned about Central Asian transport links, Russia will not object to the consolidation of trade routes in Southeast Asia, and India will have no direct interest in Northeast Asia.

To that extent, opposition will likely remain fragmented, giving China the great advantage of time and the opportunity to make progress step by step in different directions at different times, all in line with a simple formula which stresses the importance of mutual gains. As Li spells out, “You can make this compelling case. China is extremely important. We build this infrastructure link to you, you can trade with China. It will benefit you enormously.”

Unfortunately, time can also herald unwelcome changes. China prefers stable, long-term relations with other countries, but some of the New Silk Road countries are democracies, at times leading to dramatic changes in governments.

President Maithripala Sirisena’s new government in Sri Lanka has promised to review a Chinese-backed port project in Colombo that was launched by Xi Jinping in September last year, and which is already under construction. Ranil Wickremesinghe, the country’s new prime minister, had previously said the project would be cancelled if his party came to power.

Meanwhile, in Greece, Syriza, the party that has just gained power, has just suspended the sale of the port of Piraeus to China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO), who were planning to transform it into an important European hub on the New Silk Road.

The End of the Road?

Ostensibly, the New Silk Road is about trade routes and infrastructure, and to that extent it is comprehensible, if very ambitious. But behind the detail of construction projects backed by policy banks, there lie trade agreements and a conception of China’s development that looks beyond China as simply one end of a trade route. Indeed, as Song Gao makes clear, “It turns out that this vision will be much bigger than that, like turning the entire economy into a free trade zone.”

Match this vision with the macro-economic centrality the New Silk Road provides for both internationalizing the renminbi and providing a conduit for the export of Chinese capital, and the New Silk Road becomes much more than freight trains crossing wide desert plains. As historical analogies go, China as the Middle Kingdom might seem more appropriate, for the New Silk Road policy resembles less a road than a ‘roadmap’ towards China’s future, and it is a map with China firmly in the middle.

However, as CKGSB’s Li says, “the road is long, with many pitfalls”, raising the prospect that the New Silk Road may be just as hazardous as the old one.