Under the banner industrial policy, “Made in China 2025,” China is seeking to replace the advanced foreign manufactured goods that it has long relied upon with domestically-produced goods. But the effort is spooking the foreign business community, and the plan may not address China’s most genuine needs

In October 2008, the PC manufacturing giant Hewlett-Packard (HP) announced it would be opening a PC manufacturing plant in the southwestern city of Chongqing, the company’s second facility in China. At the time, Chongqing, a megacity almost on par with Beijing and Shanghai, did not produce a single computer—today it makes 35% of the world’s total, around 100 million units annually. Such is China’s success story.

But “Made in China” can be a deceptive slogan. With those HP PCs made in Chongqing, for instance, only 10% are assembled with central processing units (CPUs) that are made in China—the rest use Intel chips that are imported. The Chinese government is on a mission to change this. In 2014, it established the China IC (integrated circuit) Industry Investment Fund, worth nearly $22 billion, to advance the industry.

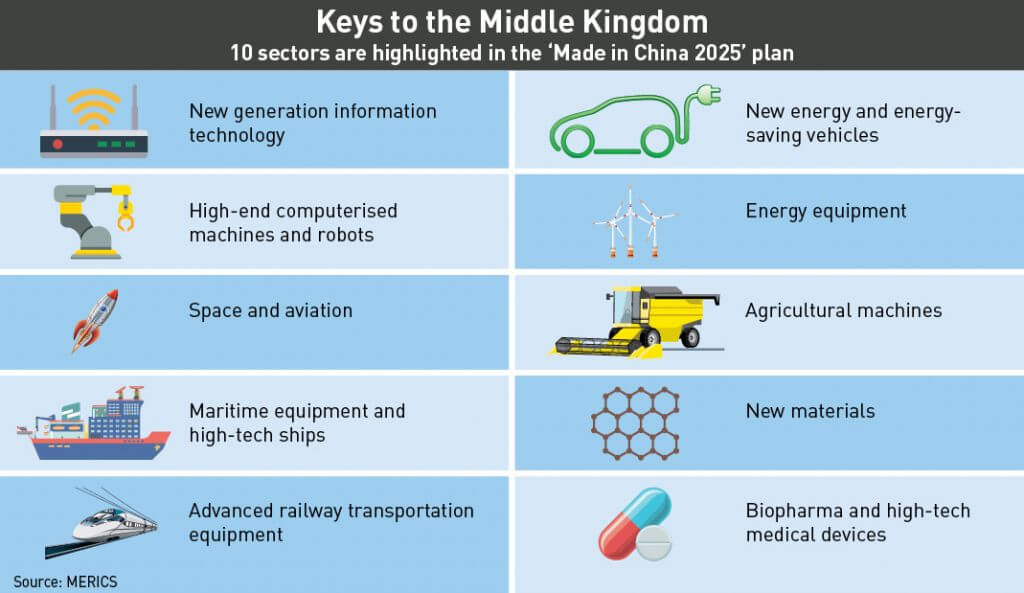

Chips, however, are only one of China’s targets. Under an ambitious policy called “Made in China 2025” (MiC 2025), unveiled in 2015, China is aiming to make 40% of so-called “core components,” that is the key parts of finished items, such as CPUs, across 10 technological areas by 2020, to be increased to 70% by 2025. In addition to IT, the 10 key areas prominently include robotics and automation, new energy vehicles and aviation. But the policy is about more than just investing money in these industries.

“Instead of just looking at those technologies in isolation, there is a focus on patent standards, getting people from different parts of the value chain to work together,” says Lance Noble, Policy and Communications Manager at the European Union Chamber of Commerce in Beijing. He describes the target sectors as force multipliers across the economy. “Perhaps you could say [the policy is] 1+1+1=10 instead of 1+1+1=3.”

But such a plan, which is explicitly aimed at substituting imports with locally-produced items, is raising concerns in the foreign business community in China, as well as from foreign governments. Some of the steps taken to progress the policy, such as government-backed cross-border mergers, have created serious political tension.

But there are also domestic reasons to question the basic premise of “Made in China 2025” and related efforts—they are fundamentally state-directed, instead of market-based. The plan to boost manufacturing “without solving concrete institutional problems, and [with] decisions [that] are not really made by entrepreneurs” is misguided, says Xu Chenggang, Professor of Economics at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business.

Precise details of the implementation of the grand policy are only now beginning to emerge. For Chinese companies, the real long-term impact of the plan is at best unclear. But for foreign companies, although there will be business opportunities in the short-term, the plan as a whole presents big challenges to their future in China.

Inclination for Innovation

“Made in China 2025” made quite a splash when it was first announced by the Chinese government in May 2015. The industrial plan is, according to the South China Morning Post and others, at least partially inspired by Germany’s similar effort, Industry 4.0, which aims to create smart manufacturing and integrated supply chains. While those goals are certainly within the framework of China’s plan, MiC 2025 spans many more industries than Germany’s initiative, with self-sufficiency in core technologies being more clearly the goal. But the plan is also a continuation of earlier Chinese policies.

“If we look at it at the abstract level, just the highlights, then it doesn’t look like anything new,” says Xu. China has long been development oriented, with ambitious targets attached to all sorts of industries, from wheat to steel. “Those kinds of central planning goals have been there all the time.”

But MiC 2025 has a more direct policy ancestry over the past few decades. The term “indigenous innovation” began to appear in the mid-1990s and referred to the need for China to advance economically by developing technologies on its own. The idea gained currency as China gained economic strength, eventually becoming an official policy in its own right.

“This drive for a new growth model actually started in 2005 under the [Hu Jintao] administration,” says Jaqueline Ives, Research Associate at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), in Germany.

MERICS released a white paper on “Made in China 2025” and its consequences for foreign business in December 2016, which also discusses the underlying economic urgency for China to advance in its manufacturing capabilities.

“Why it’s so urgent is because China faces so many challenges at the moment, [such as] the stagnating economic growth rate, [and] rising wages,” says Ives.

Pushing the process forward means changing systems and moving up the value chain—it simply is no longer good enough to be the world’s factory, even for high-end goods like iPhones. China neither produces the key parts of the iPhone, nor does it own the underlying intellectual property, which is where the true value lies.

It should also be noted that in the realm of mobile devices, China has in the past few years produced several brands that compete with Apple, including Xiaomi. But Xiaomi is still ultimately beholden to foreign companies like Qualcomm for its chipsets, and to Google for the Android operating system. Without these foreign suppliers, China’s smartphone sector would have a tough time, and that’s precisely why the government wants to push development in those key areas.

“A big part of the ‘Made in China 2025’ framework is to try to make sure that domestic companies develop the kinds of technologies that China has considered to be strategic,” says Jacob Parker, Vice President of China Operations at the US-China Business Council in Beijing.

Implementation

Making sure domestic companies develop strategic technologies is a lot easier said than done and the details of what needs to be done to meet the requirements of MiC 2025 differ significantly from one industry to the next. But one universal key component is cheap money to fund R&D, and the government is stepping up to provide this.

“[Chinese companies] could have very low-interest loans, so the cost of capital is much lower,” says Parker.

In addition to the $22 billion chip fund, Guangdong province alone has committed $150 billion to equip its factories with robots. Chinese automaker BYD, which has become a leader in electric vehicles, had received $435 million in government support by the end of 2015. Subsidies exist on the buyer side as well—purchasers of battery electric vehicles that are made in China can receive up to RMB 55,000 against the price.

But a policy of marketplace favoritism does not necessarily mean that the real goal of closing the technology gap will be achieved. This is where foreign companies may be encouraged to partner with Chinese companies and may be in a position to make a lot of money.

“Generally speaking, that [opportunity] tends to be in the areas where the technological gap is larger,” says Noble.

But these opportunities, many of which are available to joint ventures, tend to come with strings attached. Those strings may include a requirement on technology transfers and the sharing of raw data, especially in heavily emphasized areas such as smart manufacturing.

“Any time you have anything operating over the internet, especially in an automated facility, you are constantly collecting data on the health of the system and any problems that arise,” says Parker, noting developing regulations on cross-border data flows. “How you manage that data is something that will need to be considered.”

Noble warns that companies that are welcomed into the China market today because they have some technological edge might find themselves being forced out a few years later, which is exactly what happened with European companies that helped China develop high-speed rail more than a decade ago.

“Based on past experience, it’s entirely possible that this is another import substitution plan,” Noble says.

But joint ventures and other forms of cooperation are not the only way for China and Chinese companies, either owned or supported by the state, to close the technology gap. It is also possible to acquire the necessary IP and experience outright through cross-border M&A, but this has proven to be extremely controversial at times.

Manufactured Tension

In May of last year, German chip manufacturer Aixtron entered an agreement to be acquired by the German subsidiary of Fujian Grand Chip Investment for €670 million. The German government initially approved the deal in September, but put the deal on hold the next month following a vehement political outcry, not only in Germany but in the wider European Union and in the United States.

The Aixtron acquisition was far from based on market principles. According to MERICS, although Fujian Grand Chip Investment is mostly privately owned, the acquisition deal was backed and enabled by the National IC Fund. In the view of the US government, the deal was an attempt by the Chinese government to get its hands on sensitive technology, potentially with military applications—and it was the Obama administration that was finally able to scuttle the transaction in December by blocking the inclusion of Aixtron’s US arm.

“The United States, Europe, other parts of the world basically have the consensus that they don’t want the state to own and run major parts of the economy,” says Noble. “There is a major question mark of how they want to treat investment from entities that may be seen as influenced, or highly influenced by a foreign government.”

A significant compounding factor in the field of acquisitions is the increasing prominence of trade reciprocity issues—Western companies are not given the same amount of market access in China as the other way around, despite promises over many years to the contrary. Noble contrasts President Xi Jinping’s recent comments at the World Economic Forum in Davos in favor of continued globalization with the reality on the ground.

“Eventually one has to judge the authorities by their deeds, not their words,” says Noble. “We’ve seen for strategic emerging industries in the past, commitments that [foreign companies] would be given equal access, [and] equal treatment in the initiative, but in practice in solar and wind energy, low and behold, nothing of the sort happened.”

Both Noble and Ives point out that there is of course nothing inherently objectionable about acquisitions of foreign companies by Chinese companies, and in fact it is what everyone wants so long as it is based on market principles. Ironically, the real worry is that all the tensions could lead to truly win-win deals also being blocked.

“Unfortunately we could see bids by private Chinese companies that are looking to expand on a private company investment thesis get caught in the crossfire,” says Noble.

That almost happened with a big Germany-China deal last year, when Chinese white goods manufacturer Midea bid to buy German robotics maker Kuka for $5.5 billion. Ives says that in contrast to Aixtron, the Kuka deal was very much market-led. The deal almost failed to go through.

Policy vs Reform

There is also doubt about where some of the initiatives aimed at promoting MiC 2025 lead. All the state subsidies, for instance, may create yet another binge rather than a boom.

“The funding does not necessarily go to the [companies] that can benefit from it the most, but perhaps have the best connections to the government,” says Ives. She says research at MERICS had identified a number of Chinese robotics and machinery companies that had received as much as 10% of their revenue from subsidies—one even would have been in the red without the state funding help.

In fact, Ives says, the entire marketplace for robots in China is distorted and in danger of overcapacity, with 40 robot industrial parks already built or being planned, which “if you compare it to the demand, it is blown out of proportion.”

Professor Xu Chenggang of CKGSB calls out the more fundamental issue of economic reform versus industrial policy.

“They have completely separate reform plans,” Xu says, referring to the pledge by the Chinese government to allow a greater role to the market. “‘Made in China 2025’ is not in the reform plan.”

Xu’s example is that despite decades of effort, China is still unable to independently produce either the engines for the cars it makes, or the chips that power computers. The issue is not the technical difficulty, but the fact that these industries are largely state-run, and so lack the proper incentives to show initiative.

“Today you are a CEO of a large SOE, tomorrow you may become a vice minister,” Xu says. “They are not able to solve the problems because it is beyond engineering problems, it is an institutional problem.”

Xu points out that China is already home to companies that are achieving its industrial policy goals.

“In the last two decades there have been fairly successful Chinese firms, which have successfully upgraded their technology, and now they are becoming powerful competitors in the international markets, such as Huawei,” says Xu. “But these are not planned by the bureaucrats… it happened in the market.”

He adds that many companies in the manufacturing powerhouse of Shenzhen have already achieved the government’s 40% target—not through top-down policy, but free-market dynamics.

Unsurprisingly, the foreign business community also supports a market-forces-based reform approach.

“If [China] lives up to the reform agenda [it] laid out in [at the Third Plenum in] 2013, it will get you further and there will be less critical complications along the way,” says Noble.

Outlook

But however strong outside sentiment is for reliance on good old market dynamics, it seems that state-driven policy will rule the day indefinitely.

“An open liberal market economy with trade like you might see between France and Germany, or between Spain and Italy is not really in the cards for the foreseeable future you could say,” says Noble.

‘Made in China 2025’ is unlikely to be a total flop, given the amount of money and policy support behind it, and while Ives has reservations about the ability of the program to achieve its broadest goals, she also says that “a small vanguard of companies” will benefit from the policy and do well. But the real impact might be difficult to calculate given the opacity of China’s system.

“It [will be] really difficult to know if it really was achieved or not, because they want to keep face,” says Ives. “So what I would expect is that even though they will probably not realize [the goals], they will say that they did.”

Professor Xu’s hunch, meanwhile, is that the impact of MiC 2025 will at best be minimal. But he is also apprehensive about the distortions it might cause, especially in the absence of reforms.

“Without important institutional reforms, if [the government] pushes, things can get much worse,” Xu says. “It’s better it be forgotten.”