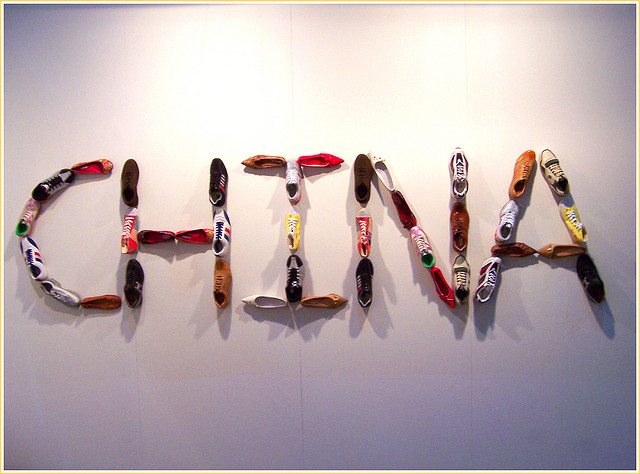

It’s time to give ‘Made in China’ a makeover.

Fifth October was recently designated as Thinkpad Day by the US state of North Carolina, a date which commemorates the 20th anniversary of Lenovo’s Thinkpad label. Lenovo, which recently gained the mantle of the world’s largest PC manufacturer, will also soon inaugurate its first US manufacturing plant. It is expected to start operations early next year and create 115 jobs. Above all, the plant is Lenovo’s Trojan horse. Reaching the US market from within means better customer service and faster delivery, a wise move aimed at repositioning the brand’s image, and moving away from the general lack of trust associated with ‘Made in China’ products.

This August, British creative agency JWT London examined this issue in great detail in a report titled Remaking Made in China. It also looked at the factors that are hampering the globalization of Chinese companies. The study highlights that “when respondents were asked to choose which phrases they associate with Chinese brands, the top 3 responses were mass-produced, cheap and poor safety standards echoing consumer sentiment around Made in China”. In most cases, this is probably because of a subconscious instinct. “People are indeed affected by this concept, regardless of the real experience consumers have had with ‘Made in China’ products,” says Zhang Kaifu, Assistant Professor of Marketing at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business.

That’s the big challenge for Chinese companies: they have to build their brand equity even as they constantly fight the negative perceptions shared by both foreign and domestic consumers, as well as multinational companies eyeing China as a place to manufacture high-tech products. It’s an uphill struggle where trust and reputation must be earned. As Zhang stresses, “The pressure comes from the fact that consumers are making choices based on the quality perception of ‘Made in China’ products. Government initiatives may help in coordinating the actions but it’s not going to be the main approach in solving the problem.”

‘Nation Brand China’ and ‘Made in China’ are at the crossroads. China’s challenges with regard to improving the perception of ‘Made in China’ are strictly linked to Brand China. As nation branding expert Simon Anholt, who has advised 53 governments over the last 14 years, explains, “People admire the countries which they believe are making the things they want to buy, teaching them the things they want to learn, fixing the things which they think are broken, and above all, making themselves useful in the community of nations. If China (or any other country) wants to be more admired, it needs to become more admirable. It’s as simple as that.”

The Beginning of a New Era

So how should China—and Chinese companies—build this desire? Moving up the value chain involves playing in a new arena: offering sophisticated quality. Consumers and ultimately society conform at this crucial point of intersection. Gang Han, author of the study Understanding Made in China: Valence Framing and Product-Country Image, says, “Public perception is affected by how mass media portrays Made in China. (This involves) factors such as ideology, culture, politics, economy or trade relationship, social norms, advertisers, interest groups and media organizations.” All of them affect consumers’ brand choices. The perception of ‘Made in China’ is evolving, bringing into the limelight issues such as innovation, management practices, environmental protection, corporate social responsibility and intellectual property. And consumers are now the judge—and the mentors—in this process of change. The country and its products are involved in a move without precedents: brand-building.

Nevertheless, if people are immune to brands, brand-building becomes useless. Therefore, a critical consumer society and strong public awareness becomes paramount. Peter McCallister, director, Ethical Trading Initiative, says, “We do know that consumers place their trust in their favorite brands and expect them to be doing the right thing, so brands ignore this at their peril.” A proper system of checks and balances can only be achieved by putting brands and companies’ performance against consumers’ expectations and evaluations. Pressure from below, instead of the current top-down approach becomes the formula to success and can only be achieved if all the stakeholders in place (government, consumers and domestic and foreign companies) work in the same direction. Brand-building means that products have to be functional, satisfy demand and more importantly, offer added value, contributing to the development of a demanding consumer.

Changing the Mentality

Centuries ago, China was one of the world’s greatest inventors: the compass, printing, papermaking, the seismometer, gunpowder, banknotes and many other things originated in China. It’s time for the world’s second-largest economy to start doing things on its own, once again. Functionality and quality are features taken for granted at this stage. Chinese brands need to be the very first in something in order to change perceptions. As Zhang explains, “‘Made in China’ is a multidimensional concept. And a lot of it is due to its contribution to society.” Many different aspects influence how Chinese products are valued by consumers and therefore, Chinese companies must rely on what their value proposition is to distinguish themselves from their competitors. Therefore, Chinese companies must rely on what they have to offer.

Partnerships with multinationals such as those embraced by high-tech companies like Huawei or ZTE may help as long as they go beyond merely sharing knowhow. Developing a culture of innovation will hence build a connection with society. Companies like SAIC, TCL, Bosideng or Li Ning are big players in China but are little known outside. If foreign consumers are to count them among their favorite brands, they’ll need to see some added value in them. According to Han, products are seen as beneficial in two ways: “At a personal level, in terms of, for instance, affordability, availability, quality, value for money or the habit of using certain products as daily necessities; and at a country level, by bringing job opportunities back to local people or benefiting the US economy from trading goods with China.” In his study, he concluded that participants perceived the product aspect of ‘Made in China’ more positively than the country aspect due to the benefits attached to the former.

And that is the big challenge. “Chinese manufacturers should continue their efforts to build China-only brands and gain recognition in Western markets. In this sense, they may have to follow the footsteps of ‘Made in Japan’ or ‘Made in Korea’,” Han explains. Given the tremendous home market advantage, Chinese entrepreneurs enjoy an advantageous position. China is, after all, the world’s largest smartphone market, the biggest grocery market, the largest auto market, the biggest energy consumer, the second-largest market for new airplanes; and by 2015, it will be the world’s largest consumer market and the top luxury market. Under such circumstances, there must be room for innovation.

Stealing Hearts and Minds

Haier landed in the US in 1999 aiming to build a brand appealing to American costumers. Back then, China Daily quoted Haier CEO Zheng Ruimin on the company’s US entry as saying, “We had to make Americans feel Haier is a localized US brand, instead of a Chinese-imported brand.” This included initiatives like investing abroad through R&D centers in the US as a way to get know-how and learn about consumer behavior and taste.

It’s a two-way street and many Chinese and foreign companies are following Haier’s steps. Take the case of General Electric (GE), which is setting up innovation centers in China with the goal of learning from Chinese consumers while taking active part in the process of upgrading facilities in China. That’s the case of Lenovo too. It gained ground in the West by acquiring IBM, and recently overtook HP. All these individual actions help deal with the negative perceptions regarding ‘Made in China’. One might wonder how these companies that seem to be moving away from their country or origin, will contribute to a better international positioning of ‘Made in China’. Simple: by doing what they are doing. Investing in their own brands.

Zhang’s current research focuses on how Chinese companies maintain their brand image when they enter a foreign market. Consumers won’t know the brand but they’ll know its country of origin. Bosideng is a good case in point. The Chinese fashion retail brand is currently expanding its reach to the UK. Still virtually unknown in London, shoppers passing by its first flagship store will probably only know that Bosideng comes from China. In order to succeed, the brand is de-emphasizing its country of origin. As quoted by The Guardian, its UK Chief Executive, Wayne Zhu, defined Bosideng as “a Chinese brand, designed in the UK and made for Europe”. Emphasizing their country of origin won’t make brands stronger or more successful. Conversely, as Zhang points out, the only way to overcome this “common label” and staying away from the negative perception attached to it is by encouraging companies to build their own brands.

It’s not a selfish strategy, but the recipe to counter popular perception. The existence of fierce entrepreneurs willing to develop strong brands will benefit the whole ecosystem, giving birth to sophistication. So when consumers make choices, they will look for the deal that gives them the most functionality, innovation and value for money. When Chinese companies earn this reputation, ‘Made in China’ will become sophisticated.

Image courtesy: Flickr user Clark di Camelot’s photostream